This series of articles began as an investigation into the true chronology of the dual monarchies of Israel and Judah. As a proponent of the so-called Short Chronology of Gunnar Heinsohn, Emmet Sweeney, Lynn E Rose and Charles Ginenthal, I was dissatisfied with the conventional chronology advocated by today’s historians and archaeologists, and I wished to see whether the Short Chronology could provide a better fit. I started this investigation with the Exodus, which I believe has some factual basis.

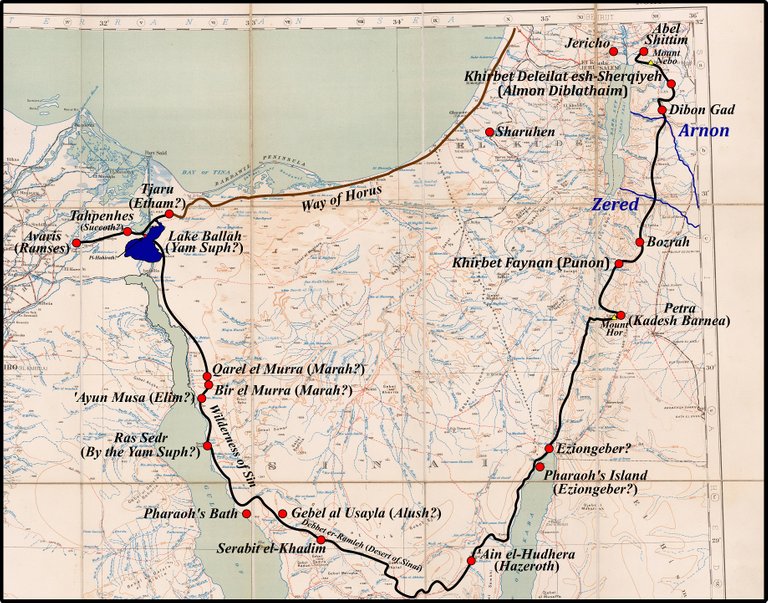

In the preceding thirty-five articles in this series, I traced a possible path of the Israelites as they made their Exodus from Avaris in the Nile Delta to Abel Shittim in the Plains of Moab. The model which I have constructed of the Exodus can be summarized thus:

The Exodus took place in 763 BCE, at the same time that the founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty, Ahmose I, expelled the Hyksos (ie the Assyrians) from Egypt.

The participants in the Exodus, the House of Israel, numbered about 6000 persons all told. They comprised the descendants of Jacob and his family, who had settled in Egypt a few generations before the Exodus, as well as their dependents.

The Israelites covered approximately 24-32 km per day (Hoffmeier 2005:120), and encamped overnight.

Initially, the Israelites set out for Jacob’s homeland in Canaan by taking the Way of the Philistines (also known as the Way of Horus). This was the military road that ran along the Mediterranean coast from the Hyksos capital of Avaris in the Nile Delta through Canaan.

When they reached the Egyptian frontier, however, they were forced to turn back and seek an alternative route. Ahmose had pursued the retreating Hyksos into southern Canaan and was now besieging them in the city of Sharuhen. The Israelites had been marching into a major theatre of war. They may even have been pursued back into Egypt by troops stationed on the frontier by Ahmose I.

The alternative route took them back along the Way of Horus to the western shore of Lake Ballah, which I have identified with the Yam Suph (the Reed Sea or the Sea of Passage, commonly called the Red Sea). Here they crossed over to the eastern shore, possibly taking advantage of a phenomenon called wind setdown.

From here they proceeded south into Sinai. The Mountain of God, where Moses is alleged to have received the Ten Commandments and where Aaron constructed the Golden Calf, I have tentatively identified with the Egyptian mining and religious site of Serabit el-Khadim. The Israelites reached Serabit by crossing the Debbet er-Ramleh, or Plain of Sand—the Desert of Sinai. They may have remained here for an extended period of time—perhaps as long as one year.

They then crossed to the eastern shore of the Sinai Peninsula and travelled north into the Arabah. I have identified Kadesh Barnea with Petra. It is possible that Petra, and not Serabit el-Khadim, was the true site of the Mountain of God. The Israelites may have remained here for up to a year, during which time Moses sent out spies to explore the southern approaches to Canaan. As a result of these expeditions, he decided to invade Canaan from the east by passing along the eastern shore of the Dead Sea and crossing the River Jordan.

The final stages of the Exodus took the Israelites through Edom and Moab, past Mount Nebo and down into the Jordan Valley.

We left them at Abel Shittim in the Plains of Moab, across the River Jordan from Jericho. It was from here that Joshua is alleged to have begun the Conquest of Canaan (Joshua 2:1).

This model is of course tentative and hypothetical. The identities of several of the Stations of the Exodus listed in Numbers 33 remain uncertain, as do many of the toponyms mentioned in the main narrative in the Books of Exodus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. Nevertheless, the model I have constructed is, I believe, plausible and fits the recorded history well at a number of places.

The date of 763 BCE for the Exodus has been taken from Charles Ginenthal:

... the people crossing the Sinai would have arrived there around June, after three-months—three new moon periods—which brings us to the pillar of light in the sky by day and of fire by night which was probably a comet, Halley’s Comet, another somewhat common event dated to 763 B.C. Duncan Steel dates the apparition of Halley’s Comet tentatively to August of 763 B.C. (Ginenthal 542)

This is highly speculative, but according to the Short Chronology the Expulsion of the Hyksos took place around the middle of the 8th century. If I am going to synchronize this event with the Exodus, then 763 is an adequate choice for a hypothesis that is still a work in progress. Note that Emmet Sweeney has chosen to follow Immanuel Velikovsky in synchronizing the Exodus with the invasion of Egypt by the Hyksos, which he dates to about 850 BCE.

Stations of the Exodus

Chapter 33 of the Book of Numbers includes a Catalogue of the Stations of the Exodus, comprising forty-two encampments where the Israelites halted overnight (or sometimes for longer periods). Some of these are easy to identify, while many others are of uncertain or unknown location. Because I have rejected as myth the Biblical claim that the Exodus lasted forty years, I have had to discard several of these stations.

1: Ramses The Exodus began in the vicinity of the Hyksos capital of Avaris. Archaeologists now believe that this was located on the same site as the later Egyptian city of Pi-Ramesse. Hence, Ramses is an anachronistic name for Avaris.

2: Succoth It is generally accepted that this is the Hebraic equivalent of the Ancient Egyptian Tjeku. Most scholars identify this with a district in the Wadi Tumilat, south-east of Avaris. In my reconstruction, however, I have the Israelites setting out from Avaris in a north-easterly direction—along the Way of Horus towards Canaan. It would be nice to be able to associate the toponym Tjeku with a district in the vicinity of Tahpanhes (which may or may not have existed at the time of the Exodus). Hitherto, I have been unable to do this, so my location of Succoth remains a weak link in my model.

3: Etham This I have identified with the frontier stronghold of Tjaru, but as James Hoffmeier noted, Unfortunately, with the knowledge presently available, the location and nature of this encampment, as well as the meaning of Etham, will have to remain uncertain. (Hoffmeier 1996:182)

4: Pi-Hahiroth Tentatively identified with a location on the western shore of Lake Ballah. The meaning is uncertain, but it could signify a place where sedge reeds grow. The Sea of Passage (Yam Suph), I surmise, was a narrow stretch of this lake.

5: Marah Tentatively identified with either Qârel el Murra or Bîr el Murra, about 15 km east of Suez. This encampment is stated explicitly to have been a three days’ march from the Sea of Passage. I have assumed that successive stations were separated by a single day’s march unless otherwise stated.

6: Elim Tentatively identified with ‘Ayun Mûsa, the Wells of Moses.

7: By the Yam Suph The inclusion of an encampment by the Yam Suph suggests that the Israelites followed the coastal route south from ‘Ayun Mûsa. I have tentatively identified this station with Ras Sudr, this particular Yam Suph being possibly the Gulf of Suez.

8: The Wilderness of Sin Tentatively identified with the low-lying desert in western Sinai, between Suez and Pharaoh’s Bath.

9: Dophkah Possibly some location in the Wadi Gharandel or the Wadi Useit. The former reaches the Gulf of Suez about 10 km north of the coastal bluffs of Jabal Hammam Fir’awn, while the latter discharges into the Gulf just north of the bluffs. I favour the wadi Useit.

10: Alush Another toponym of uncertain meaning. If the Israelites ascended Wadi Useit and then proceeded in a southeasterly direction towards the Debbet er-Ramleh (Plain of Sand), they would have passed a prominent mountain that today bears the name Gebel al-Usayla. Could al-Usayla be an echo of the Biblical Alush? In Classical Arabic, al-‘usayla means honey, which could preserve an allusion to manna. On the other hand, Gebel al-Usayla lies about 20 km from Wadi Useit. Perhaps Alush should be located beyond this mountain, somewhere in the Debbet er-Ramleh.

11: Rephidim Uncertain. Following the itinerary I am proposing, Rephidim possibly lay somewhere in the Debbet er-Ramleh close to Serabit el-Khadim.

12: The Desert of Sinai This was the location of the Mountain of God, where Moses is alleged to have received the Ten Commandments and where Aaron created the Golden Calf. I have followed Lina Eckenstein in identifying this with Serabit el-Khadim. The Israelites are said to have remained here for almost one year. Serabit overlooks the Debbet er-Ramleh, which I would identify with the Desert of Sinai.

13: Kibroth Hattaavah Unknown. Possibly somewhere between Serabit el-Khadim and ’Ain el-Hudhera, to the south of the Jabal Et-Tih (the Mountains of Wandering, on the Tih Plateau). We are told that it took the Israelites three days to reach this encampment. This makes sense, as they had to cross the arid and empty Debbet er-Ramleh after departing from Serabit el-Khadim.

14: Hazeroth Often identified with ’Ain el-Hudhera in eastern Sinai. I concur.

Stations 15-31: Taking my lead from the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, I have rejected these seventeen stations as fictitious. I believe that the Exodus was completed in less than two years, not the forty years reported in the Bible. After Hazeroth, the Israelites proceeded immediately to the thirty-second station, Ezion-Geber.

32: Ezion-Geber Located somewhere at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba. Its precise location is still uncertain, but I am inclined to favour Pharaoh’s Island.

33: Kadesh (Kadesh-Barnea), in the Wilderness of Zin Petra, in Jordan. The momentous events associated with the Mountain of God, which I have tentatively located at Serabit el-Khadim, may actually have taken place here. The nearby Mount Hor (Station 35) may have been the true Mountain of God (Horeb).

It is possible that seven or eight genuine Stations—two or three between Hazeroth and Ezion-Geber and a handful between Ezion-Geber and Kadesh—have been lost, as the Israelites must have encamped several times between Hazeroth and Kadesh. Whether these correspond to any of Goethe’s feigned stations it is now impossible to know.

34: Mount Hor Jebel Nebi Harun, close to Petra. Is Mount Hor the same as Mount Horeb? Is the Wilderness of Sinai the same as the Wilderness of Zin? Is this why Kadesh—a name which probably means holy or sacred (Strong 102)—is so called? Did the Golden Calf episode take place in the vicinity of Petra? Did Aaron die there of old age or was he executed there for his apostasy? Is Mount Hor the same as Hor Haggidgad, the 29th Station of the Exodus?

35: Zalmonah Unknown. Possibly somewhere in the Arabah.

36: Punon This toponym has been linked with that of a seasonal stream, Wadi Feynan, and the nearby archaeological site of Khirbet Faynan. This station has been associated with the plague of fiery serpents and with the brazen serpent that Moses constructed. Khirbet Faynan was noted for its copper mines, which would make it an appropriate place in which to cast a brazen serpent. In the original Hebrew text of Numbers 21, the word that is generally translated as brazen, bronze or brass is נְחֹ֔שֶׁת (nə·ḥō·šeṯ). In James Strong’s Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, however, this is translated as copper (Strong 78).

37: Oboth Unknown, but possibly located to the east of the Arabah, in the hilly uplands of the Land of Seir. The name may be related to that of Bozrah, the future Edomite capital, though Bozrah probably did not exist at the time of the Exodus.

38: Ije Abarim The Ruins of Abarim, another place of uncertain location. About 30 km north of Bozrah is the Wādī el-Ḥesā, which is generally identified with the Bible’s Brook Zered (Kitchen 194). We should, therefore, seek Ije Abarim somewhere near this wadi.

39: Dibon Gad Dibongad of Numbers 33 refers to the settlement known today as Dhībān, but it remains uncertain whether this was a genuine Station of the Exodus, or even existed at the time of the Exodus. It is probably safe to say that in their final approach to Canaan the Israelites passed within the vicinity of this location.

40: Almon Diblathaim This probably refers to an unidentified place somewhere between Dhībān and Mount Nebo. It may have been located at Khirbet Deleilat esh-Sherqiyeh, but it remains uncertain whether it was a genuine Station of the Exodus.

41: The Mountains of Abarim This station was located on or at the foot of Mount Nebo, which was also known as Abarim.

- 42: The Plains of Moab This station was located at Abel Shittim, in the vicinity of the modern Khirbet el-Khafrayn, or the nearby Tell el-Hammam. It lay directly across the River Jordan from Jericho.

And this is a good place to stop.

To be continued ...

References

- Lina Eckenstein, A History of Sinai, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London (1921)

- Charles Ginenthal, Egypt and Palestine, Pillars of the Past, Volume 3, Forest Hills, New York (2010)

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Israel in der Wüste, Noten und Abhandlungen zu besserem Verständnis des west-östlichen Divans, West-östlicher Divan, in Erich Trunz (editor), Goethes Werke, Band 2, Fifth Edition, Christian Wegner Verlag, Hamburg (1960)

- James K Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1996)

- James K Hoffmeier, Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

- Kenneth A Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids MI (2003)

- Duncan Steel, Marking Time: The Epic Quest to Invent the Perfect Calendar, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, New York (2000)

- James Strong, Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, in The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

Image Credits

- Passage of the Jews through the Red Sea: Ivan Aivazovsky (artist), , Public Domain

- The Pillar of Fire: The Art Bible, George Newnes, Limited, London (1896), Public Domain

- Looking South-East Across the Debbet Er-Ramleh: © 2014 Salma El Dardiry, Fair Use

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Joseph Karl Stieler (artist), Neue Pinakothek, Munich, WAF 1048, Public Domain

- Jebel Nebi Harun: © 2020 Dr. David L Turner, Fair Use

- Mount Nebo: Panorama from Ras Siyagha, © Madain Project, Fair Use

- Map of the Exodus: Map of the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt, the Gulf of Suez and the Gulf of Akaba, Great Britain War Office and Air Ministry, Geographical Section (1916), Public Domain

This is fascinating history 👍

Thanks for your work!

Congratulations @harlotscurse! You received a personal badge!

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking