The Restoration of Ancient History is a paper delivered in November 1994 by Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen in Germany, at a symposium in Portland, Oregon. This paper questions the conventional chronology of ancient history and offers in its place a radical reconstruction—the so-called Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the principal architect. In this series of articles, we are taking a closer look at the evidence cited in this paper in favour of Heinsohn’s new chronology:

In Heinsohn’s chronology, the history of Mesopotamia prior to the conquests of Alexander the Great comprises four periods:

| Dates BCE | Assyria | Babylonia |

|---|---|---|

| 1150-750 | Early Assyrians | Early Chaldaeans |

| 750-700 | Assyrian Empire | Assyrian Empire |

| 700-620 | Assyrian Empire | Scythians |

| 620-540 | Empire of the Medes | Neo-Chaldaeans |

| 540-330 | Persian Empire | Persian Empire |

In this article we will take a look at Part 3 of Heinsohn’s lecture: Archaeologically-missing history and historically-unexpected archaeology in major areas of antiquity. In this section, Heinsohn reviews a long list of cases where archaeologists have discovered major discrepancies between the archaeology of the Ancient World and its history as recorded by the Classical historians. These discrepancies fall into two broad categories:

Excavations in which the archaeologists failed to find strata that the recorded history had led them to expect.

Excavations in which the archaeologists discovered strata that did not seem to correspond to any cultures or civilizations mentioned in the recorded history.

Assyriologists were so stunned by the archaeological absence of Ninos-Assyrian, Medish and Persian period strata in the Assyrian “heartland of empires”, that it took them nearly one and a half centuries to draw their conclusions. In 1988, the empire of the Medes was declared missing. In l990, the Akhaemenid continent—the largest of all the empires—had to be described as elusive. The Greek claim that the first Asian superpower—Assyria of Ninos—did not emerge before -750, was not even considered worth checking. (Heinsohn)

Heinsohn noticed that many of these discrepancies came in matching pairs. The earliest such pair involved the Chaldaeans and the Sumerians:

Students of Chaldaea are stunned by the archaeological absence of the most learned nation of antiquity which the Greeks considered as the cradle of knowledge. Nobody understands how this brilliant people, which blossomed between the time of Ninos (-750) and Alexander the Great (-330), which became the teacher of nations but left no deity, text, brick or even potsherd. Yet, the same researchers take great pride in the discovery of the Sumerians (1867) in the very heartland of Chaldaea. These Sumerians became teachers of mankind. Yet, they were so ancient that even the best historians of antiquity had never heard of them. (Heinsohn)

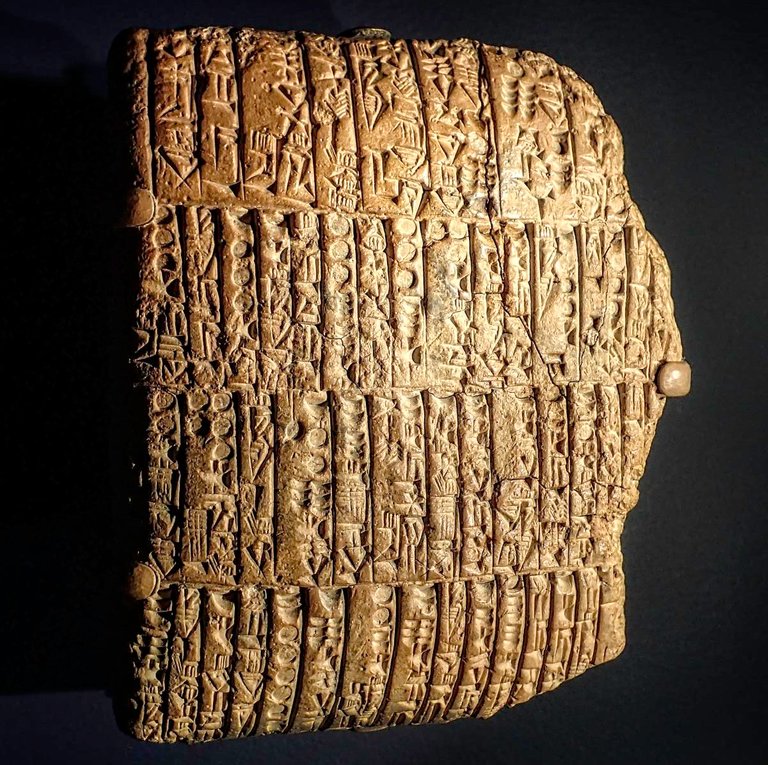

Sumerians

According to conventional archaeology, the Sumerians established the first great civilization in Mesopotamia. Around 4500 BCE, they settled in Lower Mesopotamia, built many great cities, developed advanced systems of writing and mathematics, and reached a high level of sophistication.

Between 2334 and 2218 they lost their independence when Lower Mesopotamia became part of the Akkadian Empire. When this empire was overthrown, the Sumerians were subjugated by the mysterious Gutians (2218-2047). The apogee of Sumerian power came during the following Neo-Sumerian Period, which is dated 2047-1940 BCE. For almost a century, Sumerian culture enjoyed a resurgence and once again the Sumerians became the dominant power in Lower Mesopotamia. In 1940, however, invaders from Elam brought this golden period to an end.

Around 1900 BCE, after more than two millennia of brilliant achievements, climate change and the increasing salinization of their land led to the final collapse of the Sumerian civilization, and Lower Mesopotamia became infertile and was significantly depopulated.

In the course of more than a century, archaeological excavations in Lower Mesopotamia have uncovered many of the cities of the Sumerians. Their writing has been successfully deciphered and their records read, teaching us much about this nation and their glorious civilization. But not a word of this can be found in the writings of the Classical historians. Herodotus never heard of the Sumerians. Nor did Ctesias, Berossus, Manetho, Diodorus Siculus, or any of their contemporaries. How could this be?

As Heinsohn notes, even as late as the 1st century CE, the Sumerian language was still being used—albeit as a dead tongue—which makes the complete silence of the Classical historians all the more baffling:

Sumerian writing is well-alive in astronomy up to the first century C.E. (Heinsohn)

Chaldaeans

The Chaldaeans present us with an entirely different type of problem. The Classical historians have much to say about this people. According to Berossus’s Babyloniaca, the earliest kings of Babylonia (both before and after the Flood) were Chaldaeans (Burstein 18-22). Berossus himself was a Chaldaean priest (Burstein 5). Diodorus Siculus also places the Chaldaeans amongst the earliest inhabitants of Babylonia:

But to us it seems not inappropriate to speak briefly of the Chaldaeans of Babylon and of their antiquity, that we may omit nothing which is worthy of record. Now the Chaldaeans, belonging as they do to the most ancient inhabitants of Babylonia, have about the same position among the divisions of the state as that occupied by the priests of Egypt ... (Oldfather 445)

According to conventional history, the Chaldaeans were a West-Semitic-speaking people who migrated into Lower Mesopotamia sometime between 940 and 855 BCE. For a century or so, they lived quietly under the Babylonians at the head of the Persian Gulf. Between 780 and 748 they held the throne of Babylon. After 748 they faded once again into obscurity. In 722, the Chaldaean ruler known in the Bible as Merodach-Baladan took Babylon. The Chaldaeans reached their apogee when they created the Neo-Chaldaean Empire (626-539), which lasted almost a century, before falling to Cyrus the Great and the Persians.

Note that the Sumerians too had dwelt in Lower Mesopotamia, close to the head of the Persian Gulf. Note also that Sumerian civilization collapsed around 1900 BCE when their land became infertile and unproductive. Are we to believe that by about 900 BCE, it had become fertile and productive again? Even conventional historians and archaeologists concede that the land settled by the Chaldaeans was marshy and of poor quality (Edzard 293-294). Why would anyone settle in such a region?

According to the Assyrian Emperor Sennacherib, the Chaldaeans were not marsh-dwellers. They lived in fortified cities. In 703 BCE, Sennacherib undertook a campaign against the Chaldaean Merodach-Baladan, who had recently recaptured Babylon. In his annals, Sennacherib records:

In my first campaign I accomplished the defeat of Merodach-baladan, king of Babylonia, together with the army of Elam, his ally, in the plain of Kish ... Into his palace, which is in Babylon, joyfully I entered ... In the might of Assur, my lord, 75 of his strong, walled cities, of Chaldea, and 420 small cities of their environs, I surrounded, I conquered, their spoil I carried off. (Luckenbill 116)

But of these Chaldaeans hardly any archaeological traces remain, as Dietz-Otto Edzard notes in the article Kaldu in Volume 5 of the Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie:

... other than a few personal names and some—not yet linguistically analyzed—toponyms, no material is known about the language of the [Chaldeans] ... Of the religion of the [Chaldaeans] we have learnt absolutely nothing so far. (Edzard 291 ... 294)

It is interesting that both the Sumerians and the Chaldaeans enjoyed a late flowering of their political power. In each case this renaissance lasted a little less than a century and was brought to an end by foreign invaders from the east. The Sumerians were conquered by the Elamites, and the Chaldaeans by the Persians. It is also worth noting that prior to his conquest of the Neo-Chaldaean Empire, Cyrus invaded and conquered Elam.

And this is not the only case of history repeating itself:

Prior to their renaissance, the Sumerians were ruled by the Akkadian Empire (2334-2218), after which they were subject to a people called the Gutians (2218-2047).

Prior to their renaissance, the Chaldaeans were ruled by the Assyrian Empire, after which the Scythians became for a time the dominant power in Lower Mesopotamia.

The mysterious Gutians were instrumental in bringing down the Akkadian Empire around 2200 BCE, while the Scythians were instrumental in bringing down the Assyrian Empire more than a millennium later:

Qutheans/Gutaeans help to bring down Old-Akkadians.

Scythians help to bring down Ninos-Assyrians. (Heinsohn)

Could these refer to the same historical event, duplicated by an erroneous conventional chronology? Could the Gutians and the Scythians constitute another of Heinsohn’s matching pairs?

In the last 150 years the learned world was time and again struck by the discovery of lost nations and forgotten empires which were so ancient that even the best historians of antiquity had never heard of them. This caused great surprise because these superancient civilizations were found in territories which were otherwise well known to the historians of Classical and Hellenistic Greece. Yet, the surprise did not end there. The nations and empires which were described by the classical authors in great detail could hardly be verified by the spade. One and a half centuries of excavations, thus, brought as much desperation as it did provide success stories for European scholars. Modern archaeologists ... dug in vain for the scientific splendor of the Chaldaeans on the Persian Gulf but hit the scientific splendor of much older and mysterious Sumerians. They dug in vain for marauding Scythians in Mesopotamia but hit the much older and mysterious Quthean/Gutaean marauders. (Heinsohn)

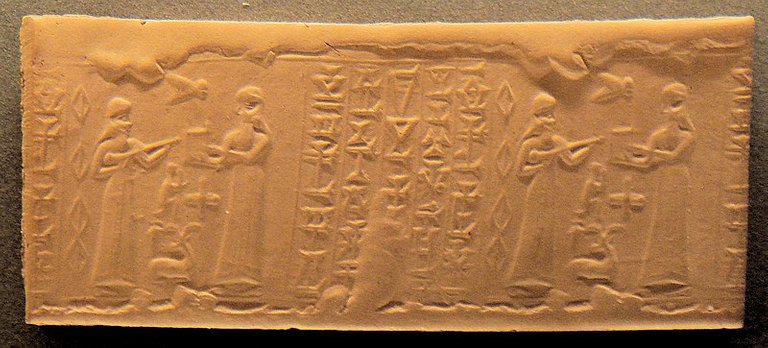

Kassites

According to conventional history, the Kassites were a people of uncertain origin who ruled Babylonia between approximately 1600 and 1150 BCE. They conquered Babylon shortly after the fall of the Old Babylonian Dynasty (Hammurabi et al). Their rule was finally brought to an end by the Elamites—the same invaders who brought the Neo-Sumerian renaissance to an end. Nevertheless, the Kassites continued to feature in Mesopotamian history for many centuries after this:

Chaldaeans/Kassites of Seleucid and Parthian Empires.

... Alexander must fight against Kassites in -330. (Heinsohn)

In the Akkadian language of ancient Babylon, the Chaldaeans were known as Kašdu. In the Bible, they are called Casdim. Were the Kassites the same people as the Chaldaeans? Heinsohn believes that the Kassites, Chaldaeans and Sumerians were one and the same:

CHALDAEA=KASDIM=KASSITES (SOUTHERN MESOPOTAMIA). (Heinsohn)

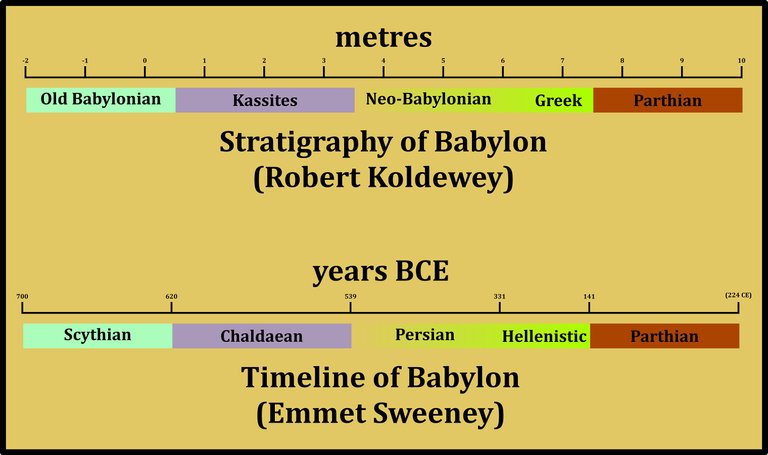

Emmet John Sweeney is one of the foremost adherents of the Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the chief architect, though there are several points of disagreement between the two. Sweeney sees the Old Babylonians as a Scythian dynasty that ruled Babylon for about eighty years during the late Assyrian Empire, from approximately 700 to 620 BCE. At this time, the Assyrian Empire still existed but was in decline. It had lost Egypt to the Eighteenth Dynasty (around 763 BCE), and now it ceded Lower Mesopotamia to its former allies the Scythians. This Scythian dynasty is the same as the Gutian dynasty that ruled Babylonia after the fall of the Akkadian Empire, while the Akkadian Empire is the same as the Assyrian Empire. The conventional chronology regards the former as two different dynasties and the latter as two different empires, each separated from the other by many centuries, but in the Short Chronology they are regarded as one and the same.

This model certainly seems to be supported by Koldewey’s Babylonian stratigraphy, which we looked at in the last article:

Sweeney has also proposed that the Kassites, whose rule in Babylonia coincided with the 18th and 19th Dynasties of Egypt, included both the Scythians and the Chaldaeans who succeeded them:

It thus seems that the earlier, virtually unknown Kassite kings, were identical to the line of kings we now call “Old Babylonian”. From the time of Burnaburiash II, however, the Kassites, who increasingly associated themselves with the earlier Sumerian (actually Chaldaean) population of Southern Mesopotamia, placed less and less emphasis on their Semitic titles, and more on their Sumerian/Chaldaean and Kassite ones.

Elsewhere I have argued in detail that the king generally known as Burnaburiash II was one and the same as the Sumerian (Third Dynasty of Ur) king Ur-Nammu, and also the same as the Babylonian ruler Nabu-apla-iddin (which could be “biblicized” to Nabopoladan or some such). The last of the Kassite rulers were therefore identical to the Neo-Chaldaean kingdom which ruled Babylonia until the arrival of Cyrus and the Persians. (Sweeney)

To summarize, then: the list of Kassite rulers is a list of the Scythian names of Babylonian kings who also had alternative Akkadian names. These include the actual Scythians who ruled Babylon between 700-620 BCE, as well as the Neo-Chaldaean kings who reigned for about a century after this (620-539) until the Persian conquest. The Elamite conquest of the Kassites, the Elamite conquest of the Neo-Sumerians, and the Persian conquest of the Neo-Chaldaeans were one and the same historical event, which actually took place in 539 BCE.

Sweeney, however, believes that the kings of Babylon who are generally said to have ruled the Neo-Babylonian Empire immediately prior to the Persian Empire were not the Neo-Chaldaeans but misdated Persian Emperors! The true Neo-Chaldaeans begin with Burnaburiash II and end with the last Kassite ruler Enlil-nadin-ahe, who was overthrown by invaders from Elam. Sweeney believes that the Persian Emperors, in their role as Kings of Babylon, adopted Akkadian titles similar to ones that had been used by the Neo-Chaldeans before them.

Sweeney’s Tentative Equations:

| Old Babylonian | Early Kassites |

|---|---|

| Sumu-Abum (founder) | Gandash (founder) |

| Sumu-la-ilu | Ushshi |

| Zabium | Abirattash |

| Apal-Sin | Tashshigarumash |

| Sin-muballit | Agum (II) |

| Hammurabi | Burnaburiash I |

| Samsu-iluna | Agum (III) |

| Abeshu | Kara-indash |

| Ammiditana | Kadashman-enlil |

| Ammizaduga | Kurigalzu |

| Samsu-ditana | Burnaburiash II |

And also:

| Later Babylonian | Kassites |

|---|---|

| Nabu-appil-iddin | Burnaburiash II |

| Marduk-zakir-shum | Kurigalzu |

| Marduk-balatsu-ikbe | Nazimarattsh |

| Nabu-shum-ishkum | Shagarakti-Shuriash |

| Nabu-natsir | Kashtiliash IV |

I intend to take a closer look at Sweeney’s model of the Short Chronology in a later series of articles. For the moment, however, this is a good place to stop.

To be continued ...

References

- Stanley Mayer Burstein, The Babyloniaca of Berossus , Sources and Monographs, Sources from the Ancient Near East, Volume 1, Fascicle 5, Undena Publication, Malibu, CA (1978)

- Dietz-Otto Edzard (editor), Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie, Volume 5, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin (1976-1980)

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volume 1, Forest Hills, NY (2003)

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volume 2, Forest Hills, NY (2008)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Frankfurt (1988)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

- Robert Koldewey, The Excavations at Babylon, Translated by Agnes S Johns, Macmillan and Co, Limited, London (1914)

- Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, Volume 2, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1927)

- C H Oldfather, Diodorus of Sicily, Volume 1, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (1946)

- Emmet John Sweeney, Empire of Thebes, or Ages In Chaos Revisited, Ages in Alignment, Volume 3, Algora Publishing, New York (2006)

- Emmet John Sweeney, The Ramessides, Medes and Persians, Ages in Alignment, Volume 4, Algora Publishing, New York (2007)

Image Credits

- Map of Chaldaea: L Thuillier (artist), Public Domain

- The Ziggurat in the Sumerian City of Ur: © Michael Lubanski, Creative Commons License

- The Cuneiform Writing of the Sumerians: Cuneiform Tablet from Nippur, Sumeria (Modern Iraq), © Mary Harrsch, Creative Commons License

- Cylinder Seal of Kassite King Kurigalzu II: © ALFGRN (photographer), Louvre Museum AOD 105, Creative Commons License

- Emmet John Sweeney: © Society for Interdisciplinary Studies (SIS), Fair Use

Online Resources