The battle of Stalingrad marked a decisive turning point in the defeat of German fascism during World War 2.

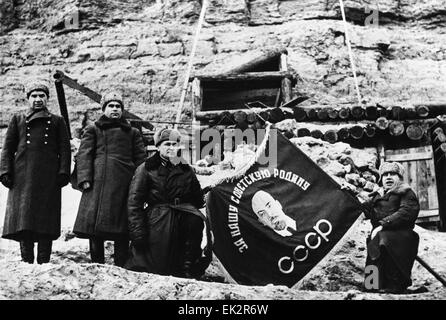

There is no land for us beyond the Volga.

Vasily Zaitsev - Red Army sniper in Stalingrad

Part 1: Operation Blau and the battles for Stalingrad September to mid November 1942

80 years ago the battle of Stalingrad raged for over five months. This life and death struggle between the forces of German fascism and the Soviet Red Army helped determine the defeat of Hitler's regime. Despite the pivotal nature of this battle, which cost the Red Army over a million casualties, it has largely been forgotten about in the West.

Public Domain

It is important that we remember all those man and women whose immense sacrifices made this victory, against all the odds, possible. This momentous battle can be regarded as a turning point in world history. If Operation Blau had been successful it would have dealt a devastating blow to the Soviet Union from which it may not have recovered. A Nazi triumph in the Soviet Union may well have changed the course of world history.

Operation Blau

The failure of Operation Barbarossa in 1941, the Wehrmacht’s plan to rapidly conquer the Soviet Union in a matter of months, left Hitler with the unenviable prospect of fighting a war on two fronts, following the entry of the United States into the war on the side of the UK and the USSR. He was acutely aware of the need to secure reliable large-scale oil supplies for the German army before the United States and the UK invaded Western Europe.

Germany's summer offensive of 1942 was given the codename Operation Blau whose primary objective was to conquer the oilfields of the Caucasus region. It envisaged a 760 kilometre advance over a combination of semi desert and mountainous terrain. Seizing the oilfields of the Caucasus would not only strike a major blow to the Soviet Union, which would be deprived of 80% of all its petroleum products, but also it would solve the greatest limitation on the German economy and war machine. Besides this, the Caucasus region contained extensive reserves of coal, peat, manganese and other raw materials.

The German summer offensive was based on the incorrect assumption that the Red Army had been so exhausted by the previous year's fighting that an additional push by the Wehrmacht would be enough to destroy large numbers of Soviet forces leading to the conquest of the Caucasus. Hitler envisaged a series of large-scale encirclement battles which would, ‘wipe out the entire defensive potential remaining to the Soviets and to cut them off as far as possible from their most important centres of war industry.’

It should be pointed out that the original German plan for its summer offensive in 1942 paid little attention to the city of Stalingrad. It considered the destruction of Stalingrad’s heavy industry by heavy artillery to be sufficient.

Hitler and his generals expected their under strength forces to pursue three strategic axes: defending the Voronezh flank, securing the Don-Volga River area around Stalingrad, and moving into the oilfields of the Caucasus. Military historians David Glantz and Jonathan House have observed that, at most, the Germans had sufficient logistics capacity to support ‘one of these axes, but not all three.'

Another major problem for Hitler was the fact that German military intelligence had repeatedly failed to appreciate how resilient the Red Army was and how it had been able to replenish its armies with new units especially in the field of mechanized/tank forces. To add to Hitler’s problems Army Group South would have to rely on the poorly equipped Axis armies (comprising Italy, Hungary and Romania) to protect the Voronezh flank from any Soviet counter-attack.

Stalin’s Flawed Thinking

Public Domain

Aware that the Germans were gathering their forces for another summer offensive the Soviet leadership failed to identify the true objective of this coming assault. Stalin and the rest of the Red Army general staff (known as the Stavka) believed that the next German offensive would again target Moscow as its primary objective. The defence of Moscow therefore receive priority in terms of weapons and new units for its defence.

Believing that the Red Army's winter offensives of 1941-42, had come close to victory, Stalin thought that a decisive victory over the Wehrmacht could be achieved through a campaign of ‘active strategic defence’. He directed the Red Army General Staff to prepare for seven local offensives, ranging from Leningrad in the north to the Kerch Peninsula in the south. It was believed that all of these offensives, occurring in late April and early May 1942, would prevent the Wehrmacht from moving reserves from one sector of the front to another. However, many of the senior officers in the Stavka feared that these limited offensives by understrength Red Army divisions would merely fritter away their strength when they would be better employed in blocking the renewed onslaught of German forces.

Operation Blau begins: the German advance to the Don and the Volga

On 28 June, the first stage of Operation Blau began which led to the capture of Vornonezh in early July. Following this Army Group South was split into two parts. Army Group B, which was composed of Sixth Army together with Fourth Panzer Army and several Axis units, was to continue the advance eastwards towards the Volga River. Meanwhile, Army Group A composed of First Panzer Army and the German Seventeenth Army, along with a variety of Axis army corps was to advance towards Rostov. After its capture Army Group A would then advance down into the Caucasus and capture the oilfields.

The second stage of Operation Blau saw the battle for the Donbass, whose capture was completed by mid July 1942. The rapid advance of German forces during this period exposed the limitations of the Red Army's command and control network. Having said this, German panzer units which had to repeatedly stop due to fuel shortages, lacked the forces to pull off the large-scale encirclements, which they had achieved in 1941. They were increasingly worn down by a stubborn Soviet defence which took its toll on their forces. Red Army soldiers in large numbers managed to escape encirclement time and again.

Impatient and increasingly distrustful of the German officer corps Hitler moved his headquarters from East Prussia to Vinnitsa in central Ukraine. From there, Hitler attempt to micromanage the advance of German forces towards the Volga and the capture of Rostov. Believing that the Red Army was near the end of its strength. Hitler and his generals continued to underestimate its ability to rebuild its shattered units and resist the German advance.

By late July Army Group A had captured the city of Rostov paving the way for the advance towards the oil fields of the Caucasus. This major defeat for the Red Army was accompanied by the loss of over 500,000 soldiers killed or captured during the months of June and July.

Buoyed up by the successful advances of Army Groups A and B, which had destroyed ten Soviet armies, Hitler was convinced that the Red Army was on its last legs. These factors intersected with Hitler feeling the pressure of time. He believed that he had to take calculated risks to achieve his objectives on the Eastern Front before the United States and UK challenged him in Western Europe.

Hitler decided to combine the objectives of phases 3 and 4 of Blau into a simultaneous operation. On 23 July he issued directive number 45 which gave Army Group B the task of capturing the city of Stalingrad rather than ‘neutralizing’ it with heavy artillery. Meanwhile, Army Group A was to proceed full steam ahead with the advance into the Caucasus.

It is worth noting that Hitler and his generals, who were very overconfident at this time, disregarding the fact that both army groups lacked the manpower to successfully achieve their assigned objectives. Glantz and House have commented that Army B, ‘… had barely sufficient combat power to advance to Stalingrad.’ Worse still, German forces assigned to defend the long flank along the Don river had a mere 100 tanks facing Soviet forces that numbered over 700 tanks. Recognizing this critical vulnerability Stalin instructed the newly formed 1st and 4th Tank Armies to launch a series of counter attacks on the flanks of Sixth Army.

Despite their shortage of combat power Army Groups A and B came ‘perilously close’ to achieving their ambitious objectives.

In the last 10 days of July the Stavka ordered repeated counter attacks on the German flanks around Voronezh. These efforts were unsuccessful. However, together with subsequent efforts they forced Sixth Army to commit poorly equipped Axis forces from Romania and Hungary to defend its overextended flanks. This would turn out to be a critical mistake for in late November the Red Army managed to break through these forces and encircle Sixth Army which was bogged down in Stalingrad.

The failure of these Soviet counter offensives together with the German advance into the bend of the Don river led an increasingly frustrated Stalin to issue his ‘Not A Step Back!’ order on 28 July. Stalin cited the huge losses of manpower and economic losses of 1941 asserting that the Soviets could not continue retreating into the vast hinterland of the USSR. In order No. 227 he declared:

We must stubbornly defend every position and metre of Soviet territory to the last drop of our blood and cling to every shred of Soviet land and fight for it to the utmost.

Photo

Echoing Stalin’s demands for “iron discipline in the ranks’’ the order stated that lower level commanders and commissars who retreated without orders from the higher command would be treated as ‘enemies of the Homeland.’

However, no amount of official sanction could make up for the inexperience and tactical disadvantages under which the Red Army suffered during the summer of 1942.

Inexperienced Red Army commanders failed to concentrate anti tank weapons and artillery into strong points that could effectively deal with German panzer forces. Anti-aircraft guns and machine guns were too dispersed to counter Luftwaffe strikes which imposed such heavy casualties among Red Army tanks units and artillery. Compounding these errors were a failure of Red Army commanders to coordinate tank and rifle armies leading to hundreds of tanks being committed in piecemeal fashion to support the infantry.

Despite this, Soviet soldiers put up a determined defence which forced the advance of 6th Army to grind to a halt by 28 July.

Hitler makes the capture of Stalingrad a priority

Frustrated by the pause of 6th Army Hitler reorganised his limited forces and on 30 July made the capture of Stalingrad a high priority. Italian 8th Army was deployed to the Don river front which freed up four German divisions to support 6th Army’s advance.

Convinced that the Red Army was fleeing Hitler ordered Paulus to attack on 7 August. Despite ferocious counter attacks by Soviet troops German forces trapped 62nd Army between two pincers near Kalach. The Wehrmacht claimed to have captured 50,000 Red Army soldiers. However, this success came at a high cost as 6th Army’s tank strength decline by 20 per cent during this encirclement operation.

The fall of Kalach convinced Stalin of the need to start organizing the defence of Stalingrad. Three senior officials from the Stavka were dispatched to guide front commander Eremenko. Several lines of defence were organized to halt the German advance towards Stalingrad. The Stavka reinforced the Stalingrad Front with 15 rifle divisions and 3 tank corps during the first three weeks of August. Alarm at the continuing German advance led to a further five rifle divisions and two tank corps being dispatched to the defence in late August.

Unfortunately, for the Red Army the German advance had led to the capture of two key railway lines west of Stalingrad. This meant that the Soviet defenders of Stalingrad had to operate on a logistical shoestring just like 6th Army, with the flow of ammunition, weaponry and food facing constant disruption.

On 10 August Paulus halted for the third and last time as he prepared for the final advance towards Stalingrad. By mid August the Wehrmacht had reached the Don river bend and damaged or destroyed six Soviet field armies from 17 July to 18 August. However, this had come at heavy cost to Army Group B. Many infantry divisions had lost ten per cent of their strength while many panzer units were greatly reduced in strength. For example, the 14th Panzer Division had been reduced to 24 tanks from the 102 it fielded in late July.

German spearheads reach Stalingrad

On 24 August the spearheads of the 16th Panzer Division reached the northern suburbs of Stalingrad.

The Soviet front commander Eremenko launched a series of counter attacks which inflicted heavy casualties on XIV Panzer Corps, 16th Panzer Division suffered over 500 casualties a day in the last week of August, which prevented the Germans from capturing Stalingrad from the march. As the panzer advance was halted the Luftwaffe launched a murderous assault on the city. According to the military historians Glantz and House it began ‘one of the most concentrated aerial bombardments of the German-Soviet conflict.’

German terror bombing of civilians

A series of round the clock air raids incinerated the wooden houses in the southern part of the city, set fire to large petroleum tanks near the Volga river and hit many factories and rail yards causing tens of thousands of civilian casualties. General Gamlet Dallakian, who was in a bunker in the city during these air raids, notes the impact of the first day of German bombing:

At least 40,000 civilians died immediately because of this raid, all of them peaceful people. War is war of course, but this was the worst act we had experienced from the Germans: they deliberately singled out civilians for mass bombing. They were not fighting soldiers they were killing defenceless women and children.

The Luftwaffe deliberately targeted many of the city’s bread factories. The entire water supply and electricity supply were knocked out. Red Army journalist Vasily Grossman, who was attached to the Stalingrad Front, describes the intensity of the German bombing in his epic novel about the battle Life And Fate:

The first Junkers flew over the factory an hour before dawn. The ensuing bombardment was quite without respite: any gap in the unbroken wall of noise was immediately filled by the whistle of bombs rearing towards the earth with all their iron strength. The continuous roar was enough to shatter your skull or backbone. It began to get light but not over the factory … It was as though the earth itself were belching out black dust, smoke, thunder, lightning...

Legendary Soviet film maker Elem Klimov, who made one of the greatest anti war films of all time – Come And See, has described how his evacuation from Stalingrad haunted him for the rest of his life:

I remember us crossing the Volga and going behind the Urals, my mom, my baby brother. … We were sitting in a shed on a ferry. … At that time it [Stalingrad] was all ablaze. The river was ablaze too, this patch of fire being 1.5 kilometres wide. They had bombed a petroleum terminal, and it all went into the water, and the water was on fire. And we were being bombed: the water reached a boiling point because of that. … Naturally, I’m burdened with very strong recollections of that hell. Because it was an excursion to hell. And it lives with me forever. And so it was a must with me to shoot a film about war.

The Soviet defenders of Stalingrad, the 62nd and 64th armies, were besieged along a narrow strip of land along the west bank of the Volga river. By the end of August the Red Army had paid a very heavy price slowing down the German advance to the Volga and into the Caucasus. Since mid July it had lost over 1,000 tanks and over 300,000 soldiers.

By early September the 6th Army together with Fourth Panzer Army prepared for their assault on the city. Even at this early stage they had suffered significant losses and were certainly not up for a prolonged urban battle which Hitler never wanted for his troops in Moscow or Leningrad. They had a long flank along the Don river that was primarily defended by weak under equipped Axis troops. Soviet counter attacks had established bridgeheads at Serafimovich and Kletskaia which were key starting points for the November counter offensive that encircled German forces in Stalingrad.

Problems for both sides

The battle for Stalingrad from early September to late November went through four phases. Each phase was dominated by German efforts to break through Red Army defences and get through to the west bank of the Volga River.

German forces were unable to carry out a classic encirclement of Soviet troops and capture the city quickly. The city that bore Stalin’s name was a long thin strand of factories and workers villages that stretched for 40 km along the west bank of the Volga river. Topography caused problems for both sides in this epic battle. Red Army troops could only be supplied across the broad Volga river leaving their supply lines exposed to aerial and artillery bombardment. Their fire support mainly came from artillery based on the eastern bank of the river.

Meanwhile, German forces were left with no alternative to conducting costly full frontal attacks which aimed at cutting Soviet forces into several segments.

Opposing Forces

At the beginning of the battle Army Group B outnumbered the Soviet defenders of Stalingrad. Colonel General Weichs, commander of Army Group B, had around 980,000 soldiers at his disposal of whom 580,000 were Germans (6th Army and Fourth Panzer Army) and 400,000 were Axis allies. Opposing them were the 550,000 men of the Stalingrad and South-eastern Fronts commanded by Colonel General A.I. Eremenko. The two key formations of the city’s defence were the 62nd and 64th Armies.

The battle for Central and Southern Stalingrad during September 1942

The first phase of the German attack occupied most of September. The objectives of the German attacks were to seize control of the city south of the Tsaritsa river and to occupy the central landing stage of the river dock area thus splitting 62nd Army into two parts. They were also tasked with capturing the dominating heights of the burial mound known as the Mamyev Kurgan.

German troops were confronted by a very different kind of warfare in the ruins of Stalingrad. No longer were they to be engaged in a blitzkrieg wall of manoeuvre, now they were to be engaged in a bloody unrelenting close quarter combat which sapped the vitality and morale of German forces.

General Hans Doerr, who fought at Stalingrad, described this first phase of the battle in his book Campaign to Stalingrad:

The battle for the industrial area stand-up, began in the middle of September, and can be described as trench or fortress warfare. The time for conducting large-scale operations is gone forever; from the wide expanses of the step planned, the one moved into the jagged gullies of the Volga hills of the corpses and ravines, into the factory area stand-up, spread out over uneven, pitted, rugged country, covered with iron, concrete and stone buildings. The mile, as a measure of distance, was replaced by the yard...

The German advance which began on 12 September pushed Red Army forces into a narrow strip of territory that encompassed the factory district in the northern part of the city and a small area in the central part of the city near the ferry. General Chuikov, commander of 62nd Army was summoned to a meeting of the joint military council for the Stalingrad and South-Western Fronts on the eastern bank of the Volga. Apparently, the glow from the fires raging in Stalingrad was so strong that there was no need to turn on the headlights of Jeeps at nigh time.

At this fateful meeting General Chuikov was told that ‘time is blood’ and that surrender was not an option for his army. According to the British military historian Anthony Beevor, in his account of the battle, Chuikov told the military council, ‘We will defend the city or die in the attempt.’

By the 14th September the position of the 62nd Army became so perilous that Stalin ordered General Rodimetsov’s 13th Guards Division to be thrown into the maelstrom. Anthony Beevor describes the nightmarish journey of the 13th Guards Division across the Volga:

They were being sent into an image of hell. As darkness intensified, the huge flames silhouetted the shells of tall buildings on the bank high above them and cast grotesque shadows. Sparks flew up in the night air. The river bank ahead was a ‘jumble of burned machines, and wrecked barges ashore.’ As they approached the shore, they caught the smell of charred buildings and the sickly stench from decaying corpses under the rubble.

It should be noted that several units of Rodimetsev’s division went straight into the counter attack in daylight in full view of German aviation suffering terrible casualties. Despite this, they succeeded in pushing the Germans back from the river shore at an enormous cost suffering 30 per cent casualties in the first twenty fours hours of combat. After the war Chuikov recalled in his memoirs that.’’had it not been for Rodimetsov’s division the city would have fallen completely into enemy hands approximately in the middle of September.’

On 24 September Hitlers’ frustration, with the failure of Army Group B to capture Stalingrad and the lack of progress by Army Group A in the Caucasus, was taken out on General Halder, chief of the General Staff, who was dismissed. Yet by 26 September the Wehrmacht controlled the southern two thirds of Stalingrad and the main landing stage on the western bank of the Volga river.

Under enormous pressure from Hitler the commander of 6th Army planned his assault on the workers villages in the north of the city with a view to capturing the factory district. This would begin the second phase of the German attempt to capture Stalingrad.

Paulus faced numerous obstacles to achieving this task. In the first phase of the battle which numbered two weeks the combat strength of 6th Army had fallen from 80,000 men to 65,000 men. He was not receiving any reinforcements to make up for these grievous losses. Meanwhile, Chuikov's 62md Army had received 40,000 reinforcements enabling it continue its stubborn defence of the city.

Glantz and House have observed that at the end of the first phase of the battle it was clear that the Wehrmacht was fighting a battle it could not win:

Stalin’s decision to defend the city had deprived the Germans of their traditional advantages of mobility, manoeuvrer, and precisely focused firepower. This forced the attackers to gnaw their way through Chuikov’s defences in fighting that resembled that of 1916-17 rather than 1941-42.

The struggle for the factory district in Northern Stalingrad – October 1942

The second phase of the struggle between the exhausted troops of the German 6th Army and Chuikov’s defenders would be fought over the ruined factories and workers villages of northern Stalingrad.

Chuikov correctly identified the focus of the next German attack and mobilised his troops accordingly. He developed new tactics of urban warfare that were very effective against the German invaders. Chuikov observed that the cohesion of German infantry, artillery and tank attacks supported by overwhelming air superiority was key to their success.

He developed tactics that would exploit the enemy’s over reliance on methods that had served them so well. Chuikov noted how panzers were reluctant to advance without infantry support, that German infantry were reluctant to engage in close quarters fighting and that the Luftwaffe was reluctant to bomb Soviet positions that were close to German trenches:

Their infantry would only go onto the offensive when their tanks had been committed. And the tanks would only attack when their aviation was above our troops. If we could spoil this orderly advance we might delay the German offensive and turn away his troops.

General Chuikov decide that his best hope lay in disrupting the enemy’s routines through ‘strong defence and counter-attack.’

Red Army front line units were instructed to stay as close to German trenches as possible thus preventing the Luftwaffe from bombing them out of fear of hitting their own troops. They developed a series of strong points which were stone or brick buildings linked up by trenches that were protected by minefields and barbed wire emplacements. In preparation for the battle for the factory district Chuikov instructed his men to develop storm groups:

I again warn the commanders of all units and formations not to carry out operations or battles with whole units such as companies and battalions. Organize the offensive primarily on the basis of small groups, with sub-machine guns, hand grenades, bottles of incendiary mixture and anti-tank rifles.

Storm groups were often employed at night time as the Soviets knew German soldiers had a dislike for fighting in the dark. Suren Mirzoyan of the 13th Guards Division described the thinking behind the use of storm groups which relied on speed and surprise:

Our storm group was based on one simple idea: to give the enemy a shock, to jolt him out of his comfortable routine. We had noticed that if we struck hard at the Germans, and took them by surprise, they tended to pull back, almost as a reflex reaction.

Storm groups would often use satchel charges to blow holes through walls or throw batches of grenades through windows. Once inside an enemy controlled building the attack would descend into savage hand to hand combat. Mirzoyan emphasized:

This kind of close combat is like nothing else. Once, you are inside a building a machine gun is no longer any use, there is no time to load it, and no room to use it effectively. Knives and small, sharp spades are the best weapons for storm group fighting – it is all about physical toughness and quick reflexes.

Despite the new innovations in tactics 62nd Army was in a dire state. Low morale, constant bombing by the Luftwaffe, a never ending stream of casualties and the unrelenting advances of a powerful enemy all combined to push this army to the brink of collapse.

Sensing that 62nd Army was approaching breaking point Chuikov reiterated Stalin’s infamous Order No. 229:

Explain to all personnel that the Army is fighting on its last line of defence; there can be no further retreat. It is the duty of every soldier and commander to defend his trench, his position – NOT A STEP BACK! The enemy MUST BE DESTROYED AT WHATEVER THE COST! Shoot soldiers and commanders who wilfully abandon their foxholes and positions as enemies of THE FATHERLAND.’’

During the second phase of the battle from 27 September to 7 October 6th Army made steady progress and took control of the workers villages in northern Stalingrad but had failed to capture the enormous factories in that area. Meanwhile, it also fought off Soviet counter attacks on its northern and southern flanks. Paulus was forced to call a halt to the attack and a lull broke out which lasted for five days.

Near the end of this second phase of the battle Stalin lambasted General Eremenko, commander of the Stalingrad Front for his failure to hold back the German advance:

I am dissatisfied with your performance in the Stalingrad Front, and I demand you undertake every measure for the defence of of Stalingrad. Stalingrad must not be abandoned to the enemy, and those parts of Stalingrad which the enemy has occupied must be liberated.

During this short lull 6th Army received some desperately needed reinforcements. Hitler reluctantly assigned three new divisions into the meat grinder that was the battle for Stalingrad. This was only achieved by taking German divisions away from the exposed northern flank of 6th Army.

Hitler and General Weichs, commander of Army Group B, made the fateful decision to leave the under equipped Romanian Third Army in defence of the southern bank of the Don opposite Red Army bridgeheads that were on the western bank of the river. Glantz and House have noted the ill-fated nature of this decision:

By assigning this vital sector to the Romanians, both Hitler and Weichs took the fateful gamble that the Red Army would not, or could not, attack there in any strength. Deployed in thinly spread positions on the open steppe, the Romanians lacked the firepower, ammunition, and provisions necessary to defend their sector.

During the lull in the fighting Paulus reshuffled his scant resources and prepared for a renewed attack on the factory district despite the fact that several of his divisions were nearing combat exhaustion.

The lull also gave the Red Army time to form new defensive lines in the factory district. Soviet air defences were also significantly improved during this short period.

During the next phase of bitter fighting (14-18 October) German units captured the tank factory and came within 300 metres of Chuikov’s command post on the Volga. The intense bloody nature of the fighting is illustrated by the horrendous losses on both sides. On 14 October two panzer divisions suffered 534 men killed and wounded. Meanwhile, 62nd Army lost over 10,000 soldiers in the same period.

How did the 62nd Army avoid defeat?

It is quite remarkable how during this period the 62nd Army managed to hold on against the German onslaught. The battle for the factories was fought out in a pitiless room by room struggle. Historian Richard Overy in his book, Russia’s War, makes the observation, `How the Red Army survived in Stalingrad defies military explanation’.

Numerous explanations have been put forward to account for this.

The role of Chuikov’s inspirational leadership was a decisive factor in keeping 62nd Army in the fight. Anatoly Mershenko, who served on Chuikov’s staff during the battle, recalls:

He was a man of incredibly strong will, very brave – almost desperately brave – and I think that if someone else had been in charge – someone with a different temperament – it would not have been possible for us to hold Stalingrad. Chuikov had a colossal energy, and it was infectious – it passed on to more junior commanders.

Richard Overy has observed that Chuikov was able to, ‘gather to together scattered, leaderless soldiers and wield them into a more effective fighting force…. [he] endured what his men endured and faced death without flinching’.

Michael Jones in his book Stalingrad: How The Red Army Triumphed, has describes how Chuikov was able to reach out and inspire his men;

Chuikov’s remarkable rapport with the ordinary combatant, a most unusual gift for a Red Army commander, lay at the heart of his extraordinary achievement: transforming the battered divisions of 62nd Army into a fighting force of stupendous power.

Another key factor that kept Red Army units in the battle was the concentrated fire of the massed ranks of artillery on the eastern bank of the Volga. The Red Army had more than one hundred artillery guns per kilometre. Victor Nekrasov, who served as a sapper on the front lines of the battle later observed that;

The finance officer who came across from the other side to give us our pay … said there wasn’t room to spit on the other shore, with a gun under every bush.

Air support for Soviet troops clinging onto the western banks of the Volga and the northern factory district also played an important role. Apparently, night time bombing raids by the Red air force had a particularly demoralising effect on German troops as did night time raids by Soviet infantry which German soldiers feared. Richard Overy notes, ‘At night a blanket of fear descended on German troops.’

Some historians point to the threat of execution which Red Army soldiers faced for abandoning their posts. The argument being Soviet soldiers had no alternative but to try and survive by fighting. Of course, this explanation does not account for the skilful and determined nature of the resistance put up against the Nazi invader. This resistance proved to be a formidable obstacle to German attempts at capturing the factory district.

Geoffrey Roberts in his account of the battle points out that German soldiers came up against the problem that:

Whatever, the Nazi propaganda might say, the sustained Soviet defence of the city suggested that the enemy had a cause they thought worth fighting and dying for, which hardly fitted the image of a degenerate, judobolshevik regime.

He explains that, ‘The vital factor was the politics and psychology of patriotic defence against a murderous enemy that threatened total destruction of Rodina – one’s native land.’

Vasily Grossman, who was despatched to the Stalingrad Front as a Red Army journalist, spoke to many soldiers about their experiences of the fighting. In his monumental novel of the battle Life And Fate Grossman compares the mood of resistance displayed by Red Army soldiers with the revolutionary mood of determination displayed by the workers and soldiers in the October Revolution:

Yes, yes! This war, and the patriotic spirit it aroused was indeed a war for the Revolution. It had been no betrayal of the Revolution to speak of Suvorov in house 6/1. Stalingrad, Sevastopol, the fate of Radischev, the power of Marx’s manifesto, Lenin’s appeals from the armoured car near the Finland station – all these were part of one and the same thing.’’

Later in the novel Grossman describes the scene in a command post which was located in the cellar of the Central Power Station. Gathered together were soldiers of different ranks from across the Soviet Union:

There were all sorts of people here. Before the war, the State had somehow kept them apart; they had never sat down at one table, clapped each other on the shoulder and said: ‘No you just listen to what I am saying!’ Here, though, beneath the remains of the burning power station, they had become brothers. And this simple brotherhood was so important that they would happily have given their lives for it.

The determined nature of Soviet resistance which was causing huge casualties for German forces, helped sap the morale and combat effectiveness of Wehrmacht soldiers. An extract from the captured diary of Wilhelm Hoffman of the 94th Division helpfully illustrate this:

September 8 – Two days of non stop fighting. The Russians are holding out with insane stubbornness …

September 16 – Our battalion plus tanks is attacking the grain elevator, from which smoke is pouring – the grain in it is burning, the Russians seem to have set it on fire themselves. Barbarism. … The elevator is not occupied by men, but by devils that no flame or bullets can destroy …

October 17 – Fighting has been going for four days with unprecedented ferocity. During this time our regiment has advanced barely half a mile. The Russian firing is causing us heavy losses. Men and officers alike have become silent and bitter...

October 22 – Our troops have captured the whole of the Barrikady factory, but we cannot break through to the Volga. The Russians are not men, but some cast iron kind of creatures; they never get tired and are not afraid of fire …

October 28 – Every soldier sees himself as a condemned man. The only hope is to be wounded and be sent back to the rear …’’

The unrelenting nature of the fighting took a terrific toll on German soldiers not used to this kind of attritional urban combat. The historian Alan Clarke, in his book Barbarossa, cites a memorable passage from the diary of a lieutenant in the 14th Panzer Division as evidence of this toll:

My God why have you forsaken us? We have fought during fifteen days for a single house, with mortars, grenades, machine guns and bayonets. Already by the third day fifty four German corpses are strewn in the cellars, on the landings, and the stair cases. The front is a corridor between burn out rooms; it is the thin ceiling between two floors. Help comes from neighbouring houses by fire escapes and chimneys. There is a ceaseless struggle from noon to night. From story to story, faces black with sweat, we bombard each other with grenades in the middle of explosions, clouds of dust and smoke., heaps of mortar, floods of blood, fragments of furniture and human beings. Ask any soldiers what half an hour of hand to hand struggle means in such a fight. And imagine Stalingrad; eighty days and eighty nights of hand to hand struggles. The street is no longer measured by metres but by corpses …

Stalingrad is no longer a town. By day it is an enormous clod of burning, blinding smoke; it is a vast furnace lit by the reflection of the flames. And when night arrives, one of those scorching, howling, bleeding nights, the dogs plunge into the Volga and swim desperately to gain the other bank. The nights of Stalingrad are a terror for them. Animals flee this hell; the hardest stones cannot bear it for long; only men endure.

By the end of October, Paulus called a halt to offensive operations by the exhausted troops of 6th Army. They had captured 90% of Stalingrad yet had failed to clear the Red Army from the northern factory district. Sixth Army losses during the battle for the factory district amounted to 12,297 men leaving the army understrength by 73,996 infantry and combat engineers. Glantz and House note that by this time in the battle German forces had been depleted to the, ‘point of being combat ineffective’ causing Paulus and Weichs to take greater and greater risks, ‘by redeploying troops from their vulnerable flanks.’

Chuikov’s position was no better. Despite a steady drip of reinforcements his 62nd Army had been reduced to around 15,000 combat troops with his forces divided into three separate enclaves. The approach of winter and ice floes on the Volga would make resupply of his troops even more hazardous. Glantz and House have observed,

Still, as long as Eremenko provided a minimum number of troops and supplies, Chuikov could deny Paulus victory simply by condemning his troops to die in place.

A ten day lull then ensued during which 6th Army commanders debated their next steps as to how to implement Hitler’s order to capture the city that bore Stalin’s name. Combat action dropped sharply as both sides regrouped and prepared for the next stage of the battle..

The Final German Advances In November

On 11 November 6th Army began its final offensive to capture the factory district. This is despite the fact that 6th Army headquarters judged that ‘42 per cent’ of battalions were exhausted. Worse still, most infantry companies were below 50 men in strength and most were amalgamated. The heavy casualties of German units is well illustrated by the following comment in a letter by Corporal August Elders to his wife on 15 November:

I was at the grave of Hillebrond from Ellers, who was killed near Stalingrad. It is located in a large cemetery where about 300 German soldiers lie. From my company there are also 18 people. Such large cemeteries, where only German soldiers are buried, are found almost on every kilometer around Stalingrad...

Anthony Beevor cites a comment by one of Paulus’ staff officers regarding Hitler’s obsession ‘with the symbolism of Stalingrad.’ This officer recalls that Hitler ordered tank drivers to be used as infantry. Panzer commanders scraped together cooks, medical orderlies and signalmen to fight instead of their precious tank crewmen.

German forces made limited progress in their attacks facing fanatical resistance from Soviet units that fought to the last man. The daily report from the Red Army’s 138th Rifle Division provides a powerful description of the fighting:

Although half encircled, 118th GRR [Guards Rifle Regiment] continued to repel the enemy attacks. Only at day’s end, when all of its men had been put out of action, the enemy completely captured 118th Gds RR’s position once the regiment had been fully destroyed. A total of 7 men, together with the wounded commander of the regiment, Lieutenant Kolobavnikov, escaped from the fighting …’’

At the end of the first days fighting very heavy casualties forced General Chuikov to send a request for 10,000 replacements to enable 62nd Army to continue the fight. Some estimates put the combat strength of 62nd Army at a mere 8,000 bayonets by this point, the equivalent of one rifle division. Many Soviet units were running out of ammunition. By the 18th November the 95th Rifle Division was reduced to fighting mainly with captured German weapons.

Despite blinding snowstorms German forces continued the attack until the 20th of November.

Fighting largely consisted of savage close quarter combat between platoon sized units for control of bunkers, buildings and even rooms in the factories. By this point in the battle morale amongst German soldiers was in sharp decline as the fighting took a terrible toll on many men who were clearly at breaking point. This is illustrated in letters many men sent home from the front. On 18 November Corporal Otto Bauer tells us in a letter home that:

Equipped with the most modern weapons, the Russian inflicts the most severe blows on us. This is most clearly manifested in the battles for Stalingrad. Here we must conquer every meter of land in heavy battles and make great sacrifices, as the Russian fights stubbornly and fiercely, to the last breath...

On the same day Corporal Walter Opperman told his brother,

Stalingrad is hell on earth, Verdun, red Verdun, with new weapons. We attack daily. If we manage to take 20 meters in the morning, the Russians throw us back in the evening...

Many German soldiers became obsessed with their impending deaths which must have undermined their fighting ability as they attempted the impossible tasks set them by Hitler. Non commissioned officer Rudolf Tikhl told his wife,

If you had an idea of how fast the forest of crosses is growing! Many soldiers die every day, and you often think: when will your turn come? There are almost no old soldiers left...

Meanwhile, soldier Paul Bolze informed a friend on 18 November that:

Yes, here you have to thank God for every hour that you stay alive. Here no one escapes his fate. The worst thing is that you have to meekly wait until your hour comes. Either an ambulance train home, or immediate and terrible death in the other world. Only a few, fortunately chosen by God, will safely survive the war at the front near Stalingrad...

This contrasts sharply with the relatively high morale of the embattled men of 62nd Army who knew their job was to hang on and wait for the Soviet counter offensives that would relieve them.

Assessment

The stalemate which existed in Stalingrad at this point can be explained by the Red Army’s ‘offensive defence’ which relied on more than just courage and endurance by Soviet soldiers.

Glantz and House note that numerous counter attacks on the flanks of Army Group B together with soviet offensives on other fronts all contributed to the defence of Stalingrad as they pinned down Wehrmacht forces and also forced the Germans to divert troops that could have been sent to fight 62nd Army. They emphasise the key importance of the ‘offensive defence’ employed by the Soviet defenders of Stalingrad:

General Chuikov and his subordinate commanders used small reconnaissance patrols to assemble a clear picture of their opponents. Each German advance encountered snipers, booby traps and ambushes. Strong points were organized for all round defence with anti tank obstacles, and cleared fields of fire. Soviet assault groups of 20 to 50 soldiers, equipped with machine guns, grenades and satchel charges, operated in between these fixed positions, crawling down sewers and breaking through walls to avoid exposing themselves in the streets. This combination of intelligence, disciple, and determination enabled 62nd Army to continue fighting when, by all conventional measures, the Germans had won.

The commander of the 297th Infantry Division, Major General Mortiz Drebber, gave the following insight to his Soviet captors as to why German attempts to capture Stalingrad had failed:

The superiority of the Russians in artillery, tanks, aviation, ammunition and human resources is the most important reason for the catastrophe of the German troops near Stalingrad.

The Russian tanks performed very well, especially the T-34 tanks. The large caliber of the guns mounted on them, good armor and high speed give this type of tank superiority over German tanks. Russian tanks were tactically well used in these last battles. The artillery worked well. It can be said that she had an unlimited amount of ammunition, this was evidenced by a strong and very dense fire raid of artillery and heavy mortars. Heavy mortars have a strong morale impact and inflict great damage. Aviation operated in large groups and very often bombed our carts, ammunition depots and transport...

As the final German assaults petered out in Stalingrad during mid November the Wehrmacht suffered a much greater defeat in the Caucasus. The attempt by Army Group A to capture the vital oilfields of that region ground to a halt 70 kilometres from the oil refineries of Grozny and much further away from the main oil fields of the Caucasus. Bad weather, enormous logistical challenges, very challenging terrain and persistent Red Army counter attacks stopped the 111 Panzer Corps.

The Red Army’s defeat of Operation Blau came at a horrendous cost in terms of casualties. From 28 June through to 17 November Soviet forces suffered 1.2 million casualties. This compares with 200,000 Axis casualties. However, the Red Army had deep reserves of trained soldiers unlike the German invaders. Even worse for the Nazis, was the fact that Soviet mass production could more than make up for heavy losses of tanks and other weaponry unlike the German war economy.

Glantz and House have observed that the failures of Army Groups A and B had a certain inevitability about them due to the dispersal of under strength forces, ‘… the German attempt to seize both Stalingrad and the Caucasus oil fields at the same time almost guaranteed that they would come up short in both efforts.’’

Hitler’s gamble to capture both Stalingrad and the Caucasus oil fields was finally ended by Operation Uranus. Launched on 19 November this well coordinated Soviet offensive led to the encirclement and ultimate destruction of an entire German field army. This defeat would leave the Wehrmacht with the impossible task of finding a million new soldiers to replace its losses. Defeat at Stalingrad inflicted a crippling blow on Hitler’s armies from which they would never recover.

.

Suggested Reading:

Anthony Beevor, Stalingrad

Alan Clarke, Barbarossa

Artem Drabkin - Red Army Infantrymen Remember the Great Patriotic War: A Collection of Interviews with 16 Soviet WW-2 Veterans

David Glantz and Jonathan House, Stalingrad

Vasily Grossman, Life and Fate

Michael Jones, Stalingrad: How The Red Army Triumphed

Richard Overy, Russia’s War

Victor Nekrasov, Front-Line Stalingrad

Geoffrey Roberts, Victory At Stalingrad

Letters from German soldiers who fought At Stalingrad can be found at:

Letters from the Battle of Stalingrad

https://www.rbth.com/society/2014/02/02/letters_from_the_battle_of_stalingrad_33751.html

Thank you for your witness vote!

Have a !BEER on me!

To Opt-Out of my witness beer program just comment STOP below

View or trade

BEER.Hey @saltycat, here is a little bit of

BEERfrom @isnochys for you. Enjoy it!Learn how to earn FREE BEER each day by staking your

BEER.Dear @saltycat, we need your help!

The Hivebuzz proposal already got important support from the community. However, it lost its funding a few days ago and only needs a bit more support to get funded again.

May we ask you to support it so our team can continue its work?

You can do it on Peakd, ecency,

https://peakd.com/me/proposals/199

Your support will be really appreciated.

Thank you!