Good day Hivers,

To get to the point immediately: I'm going to try a new format for this article. Normally I either keep strictly to a book review, or a more rant-like format on politics and society. In this article, I'm going to mix the two up, to see if the result is something satisfying to write, and hopefully for you to read as well.

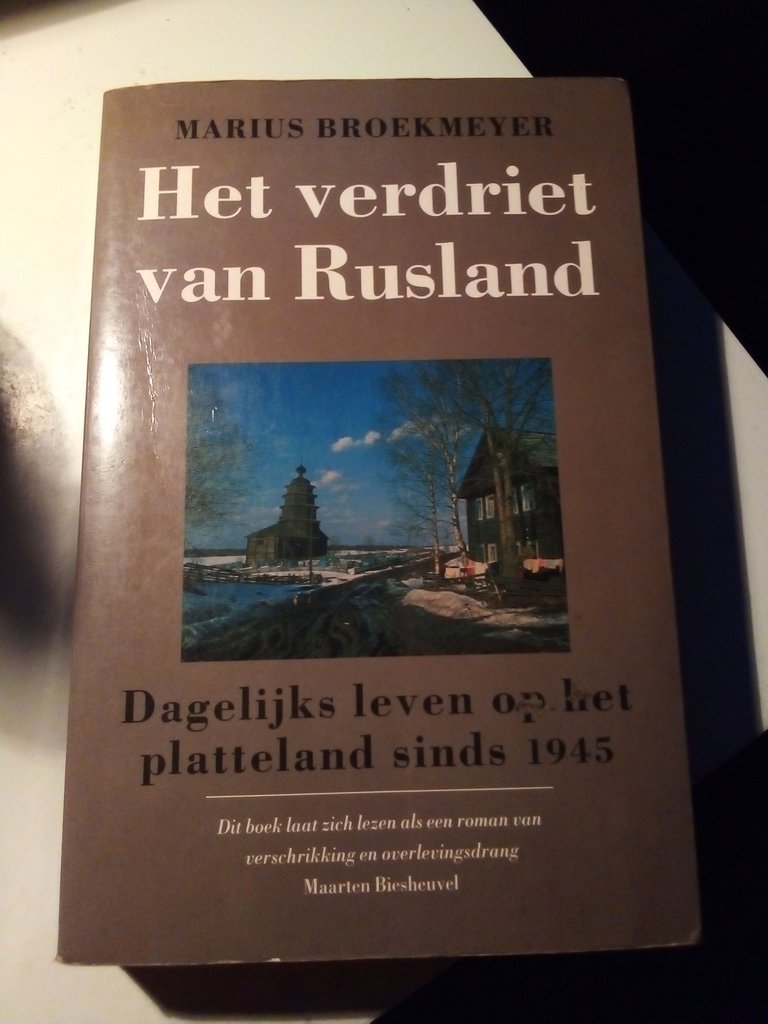

The book that got me thinking about the topic mentioned in title and sub-title, the Soviet-Russian rural economy, is a book in Dutch called 'Het verdriet van Rusland: Dagelijks leven op het platteland sinds 1945'. In English it translates to 'The sorrow of Russia: daily life in the countryside since 1945'.

Written by Marius Broekmeyer, a Dutch retired professor, in 1995, it can be seen as a retrospective on the entire post-war Soviet era (1945-1991). The book is subdivided into four parts, corresponding with the four defining leaders that span this time: Stalin, Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Gorbatsjov. Broekmeyer, along with data based on Russian and Dutch sources, also uses many literary sources to supplement the total view on Russian life in the countryside. The picture he paints isn't pretty, and shows, in my opinion, the fundamental weaknesses of the planned economy.

Collectivisation

The Russian Revolution was one of the defining moments in 20th century European history. The deposition and murder of the Romanovs, the ascent of a new upper class imbibed with the Communist ideology of radical equality/egalitarianism. In the rural areas, the disappearance of serfdom was appreciated, yet the collectivisation of the farms into either the 'kolkhoz' (plural: kolkhozes) or the 'solchoz' meant the appearance of a whole different set of issues.

Private property was despised, and though it was not attempted to be completely removed in the described period, most farmers had very little to themselves. Most farmers had a small patch of land to themselves, aside from the kolchoz, on which they tried to grow some grain, hay, or kept a cow or goat (goats were well-liked, since they weren't taxed nearly as harshly as cows).

This small side-business that farmers did was essential to their survival: because during the entire post-war Soviet era, the kolchoz-system was a mess. Firstly, the bureaucracy was massive: for every six (!) actual workers on the farm, there was a supervisor of some form. Most of what these supervisors did was giving orders from above, being a larger town-centre (rayon), the province or the state itself. Most of the supervisors that ended up in the villages and countryside did not have any expertise in agriculture, so many orders they gave were horribly counterproductive. Also, they thought of being sent to the countryside as a demotion: the cities were a much more attractive career-path for them. In return, the farmers detested their 'expertise' and their orders, but disobeying them was not an option, especially under Stalin (reigned 1924-1953). Farmers could be sent to work-camps (gulags) for years for the most minimal of 'crimes'.

Planned Economics

I mentioned the often nonsensical orders that came down 'from above'. Conceived from higher up in the Communist Party, these orders often came in a 'one-size-fits-all' form of solution. This is often the case in globalist forms of ideologies: the idea that one solution will work for all cases, all peoples, all nations, on all continents.

In the case of Soviet Russia, it pretended that all terrains worked in a similar way, which was a horrible mistake: the rich earth of the Ukraine was very dissimilar from the tundra-like Siberia, which are both nothing like the steppes of Kazachstan. A solution that might have worked in one situation, like ploughing very deeply, absolutely destroyed farmland in other parts of the Union. Talking about ploughing: it was very common in the 1950s and 1960 for farmers to do the ploughing themselves. As in: they pulled the plough themselves, not even with the proper animals. Themselves. Unthinkable to the mechanized, high-tech farming that was happening in the West at that time.

Far more things than mentioned in this article were going wrong, and because of this, harvests in the end were always sub-par. This was often covered up by creative book-keeping and straight-up lying on the parts of both farmers and commissars. If things were good on paper, the farmers might get paid some rubles, even though in reality the harvest failed completely. On the other hand, the communist system was not one for rewarding a bountiful harvest. It was 'business as usual' in that case, which led to a complete absense of motivation and overall apathy among farmers for how well their crops are doing. If more initiative was left to the farmers themselves, things would have worked out better, that much is clear.

To wrap things up

I don't think there is an English translation of the book used for this article, but I suspect that a lot of English non-fiction works have been writing about the same subject. I happened upon this book while browsing, and have found it an interesting read. In this high-tech world, and writing at this very moment in a high-tech, blockchain environment, it's good to remind oneself of how our ancestors have lived for a long time: as farmers, in a rural setting. Cities containing millions of people, electricity (not common on the Soviet countryside until the 1970s) and the internet are all very recent, and humanity's ability to adapt to it is very slow, if it will ever be complete.

I might write another article on these issues in the near future, but for now, let me know what you think of this set-up, and if there are comments/questions, do let me know. This is the non-censored part of the internet, all bets are off for an honest discussion about a touchy topic like communism. Until the next one,

**-Pieter Nijmeijer

(Top image: my own)

Congratulations @pieternijmeijer! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Your next target is to reach 3750 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPFantastic and interesting review! Curious to read this book

Glad you liked it. As said in the article, I think you're going to have a rough time finding an English translation of this particular title (wasn't successful in a short search myself)