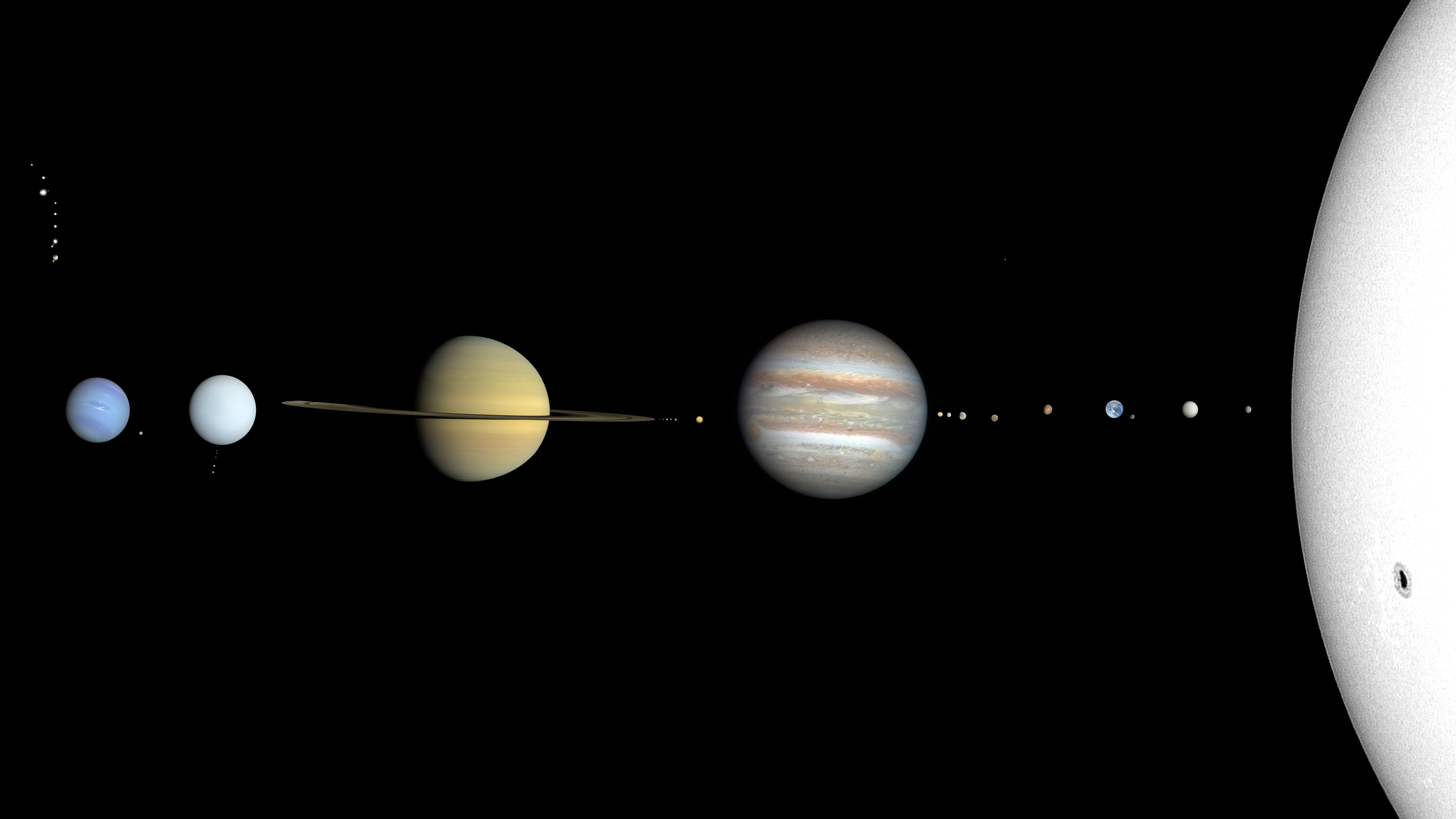

El Sol, Planetas, Planetas Enanos y Satelites del Sistema Solar / The Sun, Planets, Dwarf Planets and Satellites of the Solar System Fuente / Source

Español

Planetas, Planetas Enanos, Objetos Transneptunianos y Otras Criaturas Extrañas

Hubo un tiempo en el que para la astronomía cualquier cuerpo estelar, diferente a las estrellas, que permanecía en posiciones fijas en la bóveda celeste, era considerado un planeta; así los hoy planetas enanos como Ceres, asteroides como Vesta, o satélites como Ganimedes, Europa o Ío, eran indiferentemente considerados como planetas, sin importar cuestiones como su forma, tamaño o que objeto orbitan.

Como consecuencia de esto, el catalogo de planetas que conformaba el sistema solar estaba formado por una cantidad de cuerpos que sobrepasaba por mucho a los ocho actuales.

El concepto de planeta, cuya etimología proveniente del latín y ésta a su vez del griego, significa errante, hace referencia a aquellos cuerpos celestes que no permanecen en una posición fija en la bóveda celeste, como es el caso de las estrellas, y se remonta a la antigua Grecia, cuando se dio este nombre a los cuerpos que parecían moverse sobre el fondo “fijo” que formaban las estrellas. [1][2]

Así es como en un principio, el Sol, la Luna, y los planetas visibles a simple vista; Mercurio, Venus, Marte, Júpiter y Saturno, fueron todos considerados por igual planetas, y de una naturaleza diferente a la Tierra, que, para el momento, el auge del modelo Geocéntrico, era considerada el eje alrededor del cual giraban todos los otros cuerpos. [1][2]

Sería hasta 1610 que Galileo Galilei usara un telescopio de fabricación propia, para dirigirlo al cielo y al observar Júpiter, y descubrir cuatro de sus satélites, que se percataría de la existencia de otros objetos, que al igual que los planetas conocidos, se movían por el espacio, describiendo orbitas alrededor de otros cuerpos diferentes de la Tierra, en este caso serían los satélites, pero que, para su momento, también serían considerados, indiferentemente, planetas. [1][2]

Tras las observaciones de Copérnico y Galileo, la mecánica celeste de Kepler, sería la que pondría el clavo final al ataúd del modelo Geocéntrico, dando paso al Heliocéntrico, en el que la Tierra, pasaría a ser uno de más de los planetas que ahora orbitaban al Sol, que a diferencia de ellos no era un planeta, sino una estrella, como todas aquellas que parecían fijas en la bóveda celeste. [1][2]

Posteriormente en el año 1781, sería William Herschel, quien usando el telescopio más grande de su tiempo, descubriría un nuevo objeto que se desplazaba en medio de las demás estrellas como los planetas y que se encontraba más allá de la orbita de Saturno, originalmente pensó que se trataba de un cometa, pero tiempo después tras observar que su orbita era casi circular y se encontraba en el plano de la eclíptica, lo que difería de los cometas, se determino que se trataba del séptimo planeta, que sería denominado Urano. [1][3]

Al igual que Herschel descubriría Urano, usando un gran telescopio, una variedad de otros nuevos cuerpos también fueron descubiertos, usando estos instrumentos que empezaron a proliferar en universidades y observatorios reales, de otras instituciones e incluso personales.

Así en 1801, Giuseppe Piazzi descubriría a Ceres, en 1802 Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers, descubriría a Palas y luego en 1807 a Vesta, mientras en 1804 Karl Harding, descubría a Juno, todos ellos en el espacio entre Marte y Júpiter, en el que varios siglos antes, Kepler había calculado debía existir otro planeta. [4][5][6][7]

Por otra parte, si bien Galileo lo había observado en 1612 y luego en 1613, llegándolo a confundir con una estrella cercana a Júpiter en el cielo, fueron John Couch Adams y Urbain Le Verrier, quienes trabajando independientemente, entre 1843 y 1846, lograron calcular, basados en las perturbaciones de la órbita de Urano, la posición del que sería llamado Neptuno, mientras que sería Johann Gottfried Galle, quien en 1846 usando los cálculos de Le Verrier, y a pedido de éste, lograría observarlo por primera vez, con un grado de diferencia de la posición prevista. [8][9]

Para 1851, ya 15 objetos diferentes habían sido descubiertos en el espacio entre Marte y Júpiter, aparte de los dos nuevos más allá de Saturno, lo que motivó a crear nuevas formas de nombrar y catalogar estos cuerpos, llegando a crearse en la década de 1850, la denominación de Pequeños Planetas o Planetas Menores, para llamar a todos aquellos objetos de menor tamaño, situados entre Marte y Júpiter, siendo su primer uso formal en 1854 en el artículo “Sobre la Posición Mutua de las Órbitas de los Pequeños Planetas” de Gustav Adolf Jhan, siendo estos una subcategoría de los planetas. [5][10]

Si bien la denominación Planeta Menor era usada por buena parte de la comunidad científica, en algunos ámbitos se empleaba el término Asteroide, propuesto por Herschel en 1802, para referirse a estos cuerpos, propuesta que en su momento llegó a ser rechazada por ser considerada indigna. [11]

Ambos términos, junto al de Planetoide, propuesto por Giuseppe Piazzi, fueron empleados indiferentemente, durante buena parte del siglo XIX y todo el siglo XX, para referirse a los cuerpos rocosos que orbitaban entre Marte y Júpiter, los que pueblan los puntos L4 y L5 de la órbita de Júpiter y aquellos que se cruzan en las órbitas de los planetas interiores. [11]

Después del descubrimiento de Neptuno, nuevos estudios de las perturbaciones de la orbita de Urano mostraron que la masa de Neptuno, no era suficiente para causarlas, así que se conjeturó que debía existir otro planeta contribuyendo a provocarlas, es así como en 1906, Percival Lowell, emprendió la tarea de encontrarlo, a lo cual dedicaría su propio observatorio en Flagstaff, Arizona. [12]

Lowell moriría en 1916, sin saber que había fotografiado el esquivo planeta en marzo y abril 1915, años después, en 1930, Clyde William Tombaugh, quien sería asignado a continuar con la tarea de buscar el planeta, emplearía un microscopio de parpadeo para examinar las placas fotográficas, en las que pudo notar el cambio de posición de un objeto, que tras examinar varias fotografías más, pudo confirmarse como un nuevo planeta que recibiría el nombre de Plutón. [12]

Sin embargo, Plutón siempre representó un problema para la definición de planeta existente para el momento, para empezar su órbita era mucho más excéntrica que la de los restantes planetas, y se encontraba inclinada respecto a la eclíptica y contrario a lo que se esperaba se encontraba más cercana a la de Neptuno de lo que debía, llegando incluso cruzarse y estar más próximo al Sol que éste, durante su perihelio. [12]

La controversia se afianzaría cuando se descubrió, en 1978, que Plutón poseía un satélite, Caronte, con una masa muy parecida a la suya y que ambos se orbitaban mutuamente, en un sistema doble, donde el baricentro se encuentra fuera de ambos objetos, por lo que en algunos círculos se le llegó a denominar Planeta Doble. [12]

Fue en los años subsecuentes a la década de 1990, que con la llegada del telescopio espacial Hubble y nuevos y mayores telescopios terrestres, se empezaría a profundizar en el espacio más allá de Neptuno, encontrando la existencia de un sinfín de cuerpos con tamaños que variaban desde los muy pequeños, hasta los que incluso superaban el diámetro de Plutón, que se planteo la necesidad de reformular la definición de planeta y el cómo denominar a los otros cuerpos que conforman el sistema solar.

Es así como, en 2006, La Unión Astronómica Internacional, definió que un planeta es un cuerpo celeste que:

- Órbita alrededor de una estrella o un remanente estelar.

- Tiene la masa suficiente para que su gravedad sea tal, que haya alcanzado una forma de equilibrio hidrostático, es decir sea un esferoide.

- No emita luz propia.

- Haya limpiado su órbita de cuerpos menores, es decir tenga dominancia orbital. [1]

Según esta nueva definición, el sistema solar constaría de ocho planetas: Mercurio, Venus, Tierra, Marte, Júpiter, Saturno, Urano y Neptuno, mientras que aquellos cuerpos que orbiten a otro diferente al Sol, sería llamados satélites y para aquellos cuerpos que hayan satisfecho sólo las tres primeras características de un planeta, se creó la categoría de Planetas Enanos, así Ceres y Plutón, pasarían a recibir esta última calificación. [1]

Por su parte, se emplearía la denominación de Asteroide para llamar a aquellos cuerpos rocosos con tamaños que pueden ir desde los cincuenta metros a los 545 kilómetros, tamaño de Palas el mayor de ellos, que se encuentran entre las órbitas de Marte y Júpiter, en los puntos L4 y L5 de la órbita de Júpiter u orbitando en el sistema solar interior; mientras que el termino Meteoroide seria usado para referirse a cuerpos menores a los 50 metros de diámetro, hasta llegar al polvo cósmico. Quedando en desuso las denominaciones Planeta Menor y Planetoide. [11]

Por otra parte, para denominar a los objetos que se encuentran más allá de la órbita de Neptuno, y que su estructura está formada mayormente por rocas, se creó la denominación de Objetos Transneptunianos, encontrándose estos dispersos en tres regiones:

- Objetos del Cinturón de Kuiper, situados entre la orbita de Neptuno y las 50 UA.

- Objetos del Disco Disperso, situados en el límite exterior del cinturón de Kuiper en orbitas que tienen inclinaciones superiores a los 40° respecto a la eclíptica.

- Objetos de la Nube de Oort, situados más allá de las 50 UA con orbitas que pueden superar los 150 UA de semieje mayor. [13]

Finalmente existe una categoría adicional para denominar a aquellos planetas enanos que se encuentran más allá de la órbita de Neptuno y es la de Plutoide. [12]

Adicionalmente, se ha creado una clasificación para diferenciar los objetos del cinturón Kuiper, en relación a su resonancia respecto a Neptuno, es decir, respecto al número de órbitas que realiza Neptuno en relación a las realizadas por el objeto en cuestión, es así como se denominan:

- Plútinos: a los objetos con una resonancia 2:3 con Neptuno, es decir que realizan 2 orbitas al Sol, en el tiempo que Neptuno realiza 3.

- Twotinos: a los objetos con resonancia 1:2 con Neptuno.

- Cubewanos: a los que no tienen resonancia orbital respecto a Neptuno, estos son la mayoría de los objetos del cinturón de Kuiper. [13]

Para terminar esta clasificación, se encuentran otros dos tipos de objetos que comparten características, pero que se diferencian por la región del sistema solar de la que provienen. Los Cometas, que son objetos formados principalmente por hielo y cuyas orbitas se extienden más allá de la orbita de Júpiter, hasta incluso llegar a la nube de Oort. Y los Centauros, objetos similares a los cometas, aunque con un mayor porcentaje de rocas, y con orbitas situadas entre Urano y el cinturón de asteroides, algunos de ellos poseen anillos.

Es así como la Unión Astronómica Internacional, clasifica a la totalidad de los objetos que conforman nuestro sistema solar, clasificación que permite identificar a Ceres simplemente como un planeta enano, mientras que objetos como Plutón, pertenecen a varias categorías, siendo este al mismo tiempo, un planeta enano, un objeto transneptuniano, un objeto del cinturón de Kuiper, un plutoide y un plútino, o Cedna que puede definirse como un objeto transneptuniano, un plutoide y un objeto de la nube de Oort.

English

Planets, Dwarf Planets, Transneptunian Objects and Other Strange Creatures.

There was a time when for astronomy any stellar body, different from the stars, that remained in fixed positions in the celestial vault, was considered a planet; thus today's dwarf planets like Ceres, asteroids like Vesta, or satellites like Ganymede, Europa or Io, were indifferently considered as planets, regardless of issues such as their shape, size or what object they orbit.

As a consequence, the catalog of planets that made up the solar system consisted of a number of bodies that far exceeded the current eight.

The concept of planet, whose etymology comes from Latin and this in turn from Greek, means wandering, refers to those celestial bodies that do not remain in a fixed position in the celestial vault, as is the case of the stars, and dates back to ancient Greece, when this name was given to the bodies that seemed to move on the "fixed" background formed by the stars. [1][2]

This is how in the beginning, the Sun, the Moon, and the planets visible to the naked eye; Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, were all considered equally planets, and of a different nature to the Earth, which, by the time, the rise of the Geocentric model, was considered the axis around which all other bodies revolved. [1][2]

It would be until 1610 that Galileo Galilei used a telescope of his own manufacture, to direct it to the sky and when observing Jupiter, and discovering four of its satellites, that he would become aware of the existence of other objects, which like the known planets, moved through space, describing orbits around other bodies different from the Earth, in this case would be the satellites, but that, for his time, would also be considered, indifferently, planets. [1][2]

After the observations of Copernicus and Galileo, Kepler's celestial mechanics would put the final nail in the coffin of the Geocentric model, giving way to the Heliocentric, in which the Earth would become one of the planets that now orbited the Sun, which unlike them was not a planet, but a star, like all those that seemed fixed in the celestial vault. [1][2]

Later in 1781, it would be William Herschel, who using the largest telescope of his time, would discover a new object that moved in the middle of the other stars like the planets and was beyond the orbit of Saturn, originally thought it was a comet, but some time later after observing that its orbit was almost circular and was in the plane of the ecliptic, which differed from the comets, it was determined that it was the seventh planet, which would be called Uranus. [1][3]

Just as Herschel would discover Uranus, using a large telescope, a variety of other new bodies were also discovered, using these instruments that began to proliferate in universities and royal observatories, other institutions and even personal.

Thus in 1801, Giuseppe Piazzi would discover Ceres, in 1802 Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers, would discover Pallas and then in 1807 Vesta, while in 1804 Karl Harding, discovered Juno, all of them in the space between Mars and Jupiter, in which several centuries earlier, Kepler had calculated that there must be another planet. [4][5][6][7]

On the other hand, although Galileo had observed it in 1612 and then in 1613, confusing it with a star close to Jupiter in the sky, it was John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier, who, working independently, between 1843 and 1846, managed to calculate the planet, based on the perturbations of the orbit of Uranus, the position of what would be called Neptune, while it would be Johann Gottfried Galle, who in 1846 using the calculations of Le Verrier, and at his request, would observe it for the first time, with a degree of difference from the predicted position. [8][9]

By 1851, 15 different objects had already been discovered in the space between Mars and Jupiter, apart from the two new ones beyond Saturn, which motivated the creation of new ways to name and catalog these bodies, creating in the 1850s, the denomination of Small Planets or Minor Planets, to call all those objects of smaller size, located between Mars and Jupiter, being its first formal use in 1854 in the article "On the Mutual Position of the Orbits of the Small Planets" by Gustav Adolf Jhan, being these a subcategory of the planets. [5][10]

Although the name Minor Planet was used by much of the scientific community, in some areas the term Asteroid, proposed by Herschel in 1802, was used to refer to these bodies, a proposal that at the time came to be rejected as being considered unworthy. [11]

Both terms, together with Planetoid, proposed by Giuseppe Piazzi, were used indifferently, for much of the 19th century and throughout the 20th century, to refer to the rocky bodies orbiting between Mars and Jupiter, those that populate the L4 and L5 points of Jupiter's orbit and those that cross the orbits of the inner planets. [11]

After the discovery of Neptune, new studies of the perturbations of the orbit of Uranus showed that the mass of Neptune, was not sufficient to cause them, so it was conjectured that there must be another planet contributing to cause them, that is how in 1906, Percival Lowell, undertook the task of finding it, to which he would dedicate his own observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. [12]

Lowell would die in 1916, without knowing that he had photographed the elusive planet in March and April 1915, years later, in 1930, Clyde William Tombaugh, who would be assigned to continue with the task of searching for the planet, would use a flicker microscope to examine the photographic plates, in which he could notice the change of position of an object, which after examining several more photographs, could be confirmed as a new planet that would receive the name of Pluto. [12]

However, Pluto always represented a problem for the definition of planet existing at the time, to begin with its orbit was much more eccentric than the other planets, and was inclined with respect to the ecliptic and contrary to what was expected it was closer to that of Neptune than it should be, even crossing and being closer to the Sun than the latter, during its perihelion. [12]

The controversy would take hold when it was discovered, in 1978, that Pluto possessed a satellite, Charon, with a mass very similar to its own and that both orbited each other, in a double system, where the barycenter is outside both objects, so that in some circles it came to be called Double Planet. [12]

It was in the years following the 1990s, with the arrival of the Hubble space telescope and new and larger ground-based telescopes, that they would begin to delve into space beyond Neptune, finding the existence of a myriad of bodies with sizes ranging from very small, to those that even exceeded the diameter of Pluto, which raised the need to reformulate the definition of planet and how to name the other bodies that make up the solar system.

Thus, in 2006, the International Astronomical Union defined a planet as a celestial body that:

- Orbits around a star or a stellar remnant.

- Has sufficient mass so that its gravity is such that it has reached a form of hydrostatic equilibrium, i.e. is a spheroid.

- It does not emit light of its own.

- Has cleared its orbit of minor bodies, i.e. has orbital dominance. [1]

According to this new definition, the solar system would consist of eight planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, while those bodies orbiting other than the Sun, would be called satellites and for those bodies that have satisfied only the first three characteristics of a planet, the category of Dwarf Planets was created, so Ceres and Pluto, would receive the latter qualification. [1]

On the other hand, the denomination of Asteroid would be used to call those rocky bodies with sizes that can go from fifty meters to 545 kilometers, size of Palas the biggest of them, that are between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, in the points L4 and L5 of the orbit of Jupiter or orbiting in the inner solar system; while the term Meteoroid would be used to refer to bodies smaller than 50 meters in diameter, until reaching the cosmic dust. The terms Minor Planet and Planetoid are no longer used. [11]

On the other hand, to denominate the objects that are beyond the orbit of Neptune, and that its structure is formed mostly by rocks, the denomination of Transneptunian Objects was created, being these scattered in three regions:

- Kuiper Belt Objects, located between Neptune's orbit and 50 AU.

- Objects of the Dispersed Disk, located in the outer limit of the Kuiper belt in orbits that have inclinations greater than 40° with respect to the ecliptic.

- Oort Cloud objects, located beyond 50 AU with orbits that can exceed 150 AU semi-major axis. [13]

Finally there is an additional category to denote those dwarf planets beyond the orbit of Neptune and that is Plutoid. [12]

Additionally, a classification has been created to differentiate the objects in the Kuiper belt, in relation to their resonance with respect to Neptune, i.e., with respect to the number of orbits made by Neptune in relation to those made by the object in question, this is how they are called:

- Plutinos: objects with a 2:3 resonance with Neptune, that is to say that they make 2 orbits to the Sun, in the time that Neptune makes 3 orbits.

- Twotinos: objects with a 1:2 resonance with Neptune.

- Cubewanos: to those with no orbital resonance with respect to Neptune, these are most of the objects in the Kuiper belt. [13]

To conclude this classification, there are two other types of objects that share characteristics, but are differentiated by the region of the solar system from which they originate. The Comets, which are objects formed mainly by ice and whose orbits extend beyond the orbit of Jupiter, even reaching the Oort cloud. And the Centaurs, objects similar to comets, although with a higher percentage of rocks, and with orbits located between Uranus and the asteroid belt, some of them have rings.

This is how the International Astronomical Union classifies all the objects that make up our solar system, a classification that allows us to identify Ceres simply as a dwarf planet, while objects such as Pluto belong to several categories, being at the same time a dwarf planet, a transneptunian object, a Kuiper belt object, a plutoid and a plutino, or Cedna, which can be defined as a transneptunian object, a plutoid and an object of the Oort cloud.

Referencias / Sources

- Wikipedia, Definición de planeta, Wikipedia

- Asociación Para el Desarrollo e Impulso de la Astronomía, Planeta: origen y significado, Asociación Para el Desarrollo e Impulso de la Astronomía.

- Asociación Para el Desarrollo e Impulso de la Astronomía, El descubrimiento de Urano, Asociación Para el Desarrollo e Impulso de la Astronomía.

- Wikipedia, Ceres (planeta enano), Wikipedia.

- Wikipedia, (4) Vesta, Wikipedia.

- Wikipedia, (2) Palas, Wikipedia.

- Wikipedia, 3 Juno, Wikipedia.

- Asociación Para el Desarrollo e Impulso de la Astronomía, Predicciones sobre el octavo planeta, Asociación Para el Desarrollo e Impulso de la Astronomía.

- Wikipedia, Neptuno (planeta), Wikipedia

- Hilton, J., When did the asteroids become minor planets?, USNO.

- Wikipedia, Asteroide, Wikipedia.

- Wikipedia, Plutón (planeta enano)

- Astrosigma, Objetos transneptunianos, Astrosigma

Con el apoyo de la familia.

Trail de TopFiveFamily

Creatures? Lol dont agree much using thus term

But i liked all the info

!1UP

You have received a 1UP from @gwajnberg!

@stem-curator

And they will bring !PIZZA 🍕.

Learn more about our delegation service to earn daily rewards. Join the Cartel on Discord.

I gifted $PIZZA slices here:

@curation-cartel(16/20) tipped @amart29 (x1)

Send $PIZZA tips in Discord via tip.cc!

Thanks for your contribution to the STEMsocial community. Feel free to join us on discord to get to know the rest of us!

Please consider delegating to the @stemsocial account (85% of the curation rewards are returned).

You may also include @stemsocial as a beneficiary of the rewards of this post to get a stronger support.

Congratulations @amart29! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s):

Your next target is to reach 140000 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out the last post from @hivebuzz:

Support the HiveBuzz project. Vote for our proposal!