With the publication of Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage, Wizards of the Coast not only resurrected one of the most famous boxed sets in Forgotten Realms history, but also introduced Fifth Edition players to an aspect neglected by the company in the previous couple of decades: the megadungeon.

But what exactly is a megadungeon? How is it different from any other traditional adventure or adventure path? What should Dungeon Masters know before they consider introducing one into the campaign, and what should players be aware of before loading up on supplies and marching off to loot it?

Polish up your dice, dust off those character sheets, and make sure someone in the party can cast Light. Let's start 2021 off by preparing you for the hellish tour of duty (on both side of the screen) that is the megadungeon.

What in Tasha's Name is a Megadungeon?

As you probably surmised from the name, a "megadungeon" is a dungeon of unusual size. But simply being a large zone to explore with lots of keyed encounter areas does not necessarily make something a megadungeon. The various campaigns produced by Wizards of the Coast, such as Curse of Strahd and Tomb of Annihilation, might be multi-hundred page epics of danger and intrigue, but while they are meant to provide weeks or even months of entertainment, they aren't megadungeons.

In fact, of all the adventures published by Wizards which aren't Dungeon of the Mad Mage, only Dead in Thay, which appears in Tales From the Yawning Portal, comes close, what with its enormous map and singular underground citadel with over 100 encounter areas. Scott Gray wrote it as a tribute both to meat grinder modules like Tomb of Horrors and underground-themed campaigns like Night Below. But even Dead in Thay is lacking that certain something -- if it is a megadungeon, then it's definitely on the smaller side, akin to a moving van as compared to a tractor trailer. You can cram a lot of stuff into a moving van, but that 18-wheel semi won't be intimidated by your U-Haul.

So look at it like this: most campaigns will consist of the PCs wandering through various locales, travelling from town to town, exploring smaller locations, heading back to town to resupply from time to time, then going back in.

A megadungeon, by contrast, makes an explicit assumption the PCs will be exploring an area so large as to make frequent retreats to re-arm and re-supply impossible or too costly to consider except in emergencies. When you're poking through the ruins of the Sunless Citadel, you know the town of Oakhurst is only a couple of hours away. When you're delving into Undermountain, unless you're only testing the waters, there will come a point when it may cost you more in resources to backtrack than it will to push forward. Megadungeons are all about putting the pressure on the players to see how far they're willing to push ahead.

Where Did Megadungeons Come From?

Believe it or not, the megadungeon (or at least the concept of it) has been with the game from the very start. Both Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson incorporated the ideas into their home-built campaigns -- Gygax with the enormous, ever-expanding dungeon (at least twelve levels' worth) beneath the ruins of Castle Greyhawk, and Arneson held sway over a similarly massive subterranean structure beneath Castle Blackmoor. Ed Greenwood was quick to follow suit, developing and teasing out the colossal labyrinth of Undermountain beneath the city of Waterdeep in his Forgotten Realms world.

But of course the OG masters of the dungeon would devote months and years designing inverted Empire State Buildings for their players. What about the guys who just bought the boxed set and were setting out to build their own worlds?

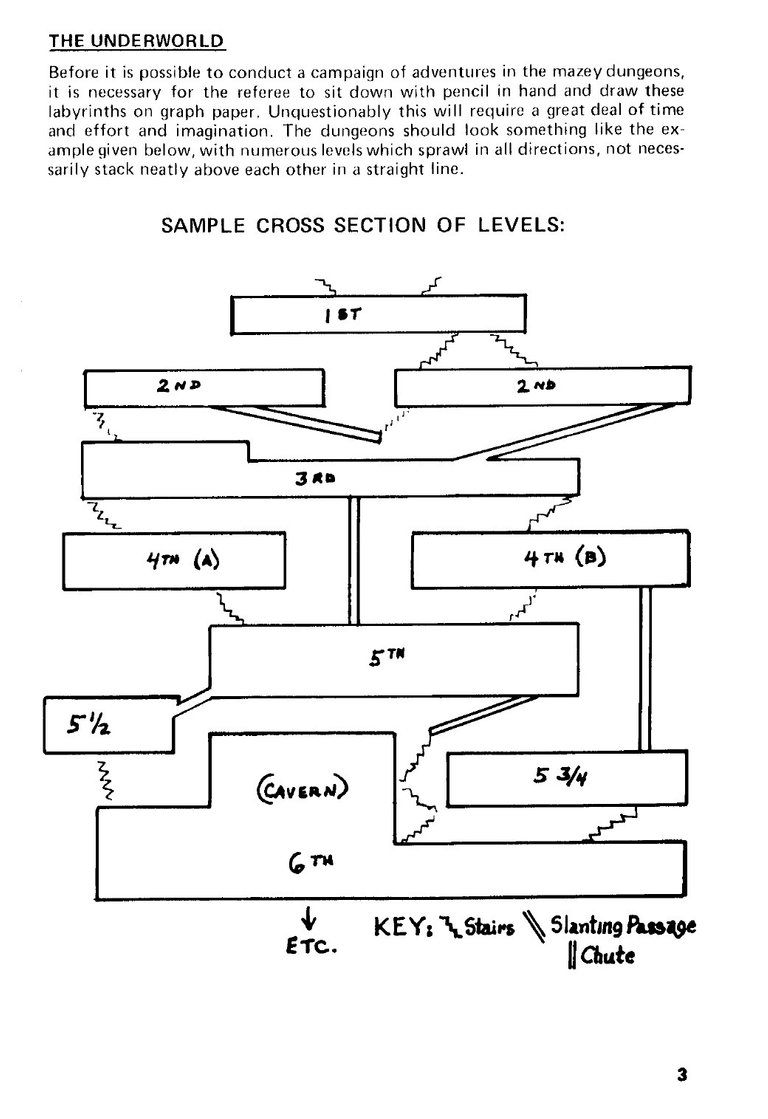

Well, we can answer that with a quick look at Underworld and Wilderness Adventures, the third booklet which came in the very first edition of the D&D game and was intended to teach the newly-christened referee (technically they weren't "Dungeon Masters" yet) how to start putting together a world for his victims players. After the table of contents, this is the very first page the reader lays eyes on:

That's Arneson and Gygax flat-out telling you to start your own campaign by sketching out a gawddamn megadungeon. But they're not finished. The book continues on the next page:

In beginning a dungeon it is advisable to construct at least three levels at once, noting where stairs, trap doors (and chimneys), and slanting passages come out on lower levels, as well as the mouths of chutes and teleportation terminals.

A few sentences later, Gygax clobbers the poor new referee with this pronouncement:

A good dungeon will have no less than a dozen levels down, with offshoot levels in addition, and new levels under construction so that players will never grow tired of it. [...] "Greyhawk Castle", for example, has over a dozen levels in succession downwards, more than that number branching from these, and not less than two new levels under construction at any given time. These levels contain such things as a museum from another age, an underground lake, a series of caverns filled with giant fungi, a bowling alley for 20' high Giants, an arena of evil, crypts, and so forth.

There are only two possible reactions to that paragraph. The first is for the reader to fold themselves up into a little ball and weep at the prospect of all that work. The other is a creativity boner savage enough to shatter the windows of your neighbor's house as you bellow, "HELL YEAH, TIME TO BUILD A DUNGEON!"

Assuming you fall into the latter category, let's continue our explorations, shall we?

Megadungeons And Players

Despite the game's primary writers instructing DMs to build megadungeons for their gaming groups, many players never saw the inside of one until the publication of the aforementioned Ruins of Undermountain boxed set in 1991, seventeen years after the game's first release. Why the long wait, when clearly Gygax had his own megadungeon all ready to go, complete with area notes and full maps?

The truth is, Gygax and Arneson never intended for TSR to publish pre-written content for the game they had created. In their minds, part of playing a game called "Dungeons and Dragons" involved somebody building the "dungeon" which would contain the "dragon". Referees would know best what suited their own table's play styles, and could construct a campaign around what their players wanted to experience. Running a dungeon somebody else built seemed the height of absurdity: only the person who crafted the place could instinctively understand the ins and outs, the reasons why areas were what they were and contained what they did. A dungeon was something beyond notes kept in a binder and a few maps sketched out on graph paper. Authors, for instance, shared only the novel which came out of their imaginations -- they did not provide all the other behind-the-scenes things like notes on character traits and aspects of the world which never came up in the story but were nonetheless foremost in the writer's mind and allowed them to craft the final product.

What's more, a megadungeon was meant to be an ever-evolving, living organism which changed and morphed based on the actions of the players. Arneson's Castle Blackmoor may have started out as a simple map and list of encounters, but after six months, his players had looted whole floors, triggered traps, felled enemies, crafted alliances, and re-worked the level geometry by tunneling through walls, floors, and ceilings, while Arneson had introduced new hazards to replace the old ones, caved in passageways, opened new levels and side-floors, and done all the other things a good referee was supposed to do to maintain the illusion of an ever-changing, ever-challenging environment. This aspect of the dungeon's design meant it was impossible to capture more than a single snapshot of the dungeon as it stood. Even starting from the same point, after a few weeks Arneson's Blackmoor would look nothing like anyone else's version despite identical notes and maps.

Gygax wasn't averse to sharing his creations with other people; in fact, another member of his gaming group, Rob Kuntz, often stood in for Gygax as Dungeon Master when Gary wasn't available, and one would explain any changes which had occurred in the dungeon during the time the other wasn't around to witness such things firsthand. But who else except a close friend who had an instinctive understanding for such a creation could possibly work with another DM's notes?

The demand for pre-written, pre-scripted scenarios took the designers completely by surprise. Gygax attempted to alleviate this by having TSR publish adventures fleshed out from scenarios originally scripted for competitive, tournament-level play, but the more modules TSR published, the more gamers demanded. The more players learned of the incredible worlds populated by people like Ed Greenwood and Gary Gygax, the more they wanted to see those worlds for themselves.

The Fall of the Megadungeon

But even the release of Ruins of Undermountain couldn't satiate the demand. For one thing, while the boxed set contained an utterly enormous amount of space, with no fewer than four fold-out, poster-size maps which detailed the dungeons first three floors, it left much of that space empty, to be filled in by the DM who purchased it. Keyed encounters were only written for about 20% of the overall playing space, and even then, passages weaved off the edges of the map allowing for even further expansion outwards and downwards. DMs who thought they were getting the entirety of Greenwood's Undermountain in ready-to-run format were in for plenty of sleepless nights coming up with material to fill all that undeveloped space.

What's more, as the years went by and gamers broadened their desires beyond simple murderhoboing, the megadungeon became seen as old and out of touch. Sure, that might have been the way the old guard put together adventures, but now players wanted the Dungeon Master to provide more than doors to kick in and monsters to kill. They wanted stories to tell, of their heroes being heroic in ways not related to slaying trolls and counting coins. Megadungeons were essentially blank slates the PCs used to write their own exploits at their own pace; any stories they told came from what the players chose to do, as opposed to any overriding reason why they should even be there in the first place. They made stories with an obvious beginning, middle, and end almost impossible to tell.

What's more, one of the key things which bound players together were the shared stories they could bring to the table. Every gamer of a certain age has their own tale about how his group got wiped out in the Tomb of Horrors, or how her party navigated the Ghost Tower of Inverness, but the freeform structure of a megadungeon meant two groups could sit down to play the same adventure and be unable to relate to anything the other encountered beyond the starting rooms.

Eventually megadungeons were seen as lazy and outdated, both by DMs and players. What's more, the occasional attempt to revive them more often than not produced coal rather than diamonds.

Looking at you, World's Largest Dungeon. /glare

By the time the 21st century dawned, megadungeons were more often met with eye-rolls as opposed to applause, and even the popular ones like Rappan Athuk appealed only to a small contingent of role-players.

That's not to say people stopped making them and players stopped wanting them -- obviously Wizards brought back Undermountain for a reason, and other designers enjoyed messing with the concept, like Monte Cook's The Banewarrens and Gygax's Necropolis -- but more often than not, the megadungeon is seen as a gimmick: it has its place, but more often than not, that place is on some wistful DM's bookshelf instead of front and center in Friday evening's campaign.

Where to Go From Here?

In part II of this article, we'll look at the logistics required to both run and survive a megadungeon, no matter which side of the screen you're sitting on. It's an experience which is not for everyone, but there are a few things you should know if you're going to participate in one, whether you're building it by hand or using a product like Barrowmaze or Dungeon of the Mad Mage.

What's your favorite megadungeon? Let me know if you like or dislike the concept, and share your favorite (or least-favorite) memories of what megadungeons did to your sanity as either PC or DM. Until next time, welcome to 2021, and may all your hits be crits!

The original Diablo game from Blizzard was essentially a megadungeon. Add a party instead of a single player, and you're in old-school D&D territory.

I'd like to see a sourcebook focusing on the ultimate D&D megadungeon, though: The Underdark. A few small maps where prior adventurers had visited and returned linking to overworld locations, and a trove of adventure hooks and DM tips for the spaces in between where no one managed to return, if they have been visited before at all.

It's rather sad, but computers certainly do megadungeons better than human players. Especially games like Diablo and Torchlight, where areas are procedurally generated, making it feel like a DM is making it up as they go along.

I could see Wizards re-visiting the Underdark; it wouldn't be difficult to use Night Below as a starting point for an Underdark campaign the way they used Ruins of Undermountain and its various sequels and expansions to help build Dungeon of the Mad Mage.

The sourcebook you're asking for could comprise a thousand or more pages (which would be EPIC!), considering all the content produced for the setting over the years, not least of which would be 1E's GDQ series, 2E's Drow of the Underdark sourcebook and Menzoberranzan boxed set (also the computer game of the same name and the aforementioned Night Below), 3.5E's City of the Spider Queen, the Neverwinter Nights computer game series, and (of course) all of R.A. Salvatore's Drizzt novels.

We don't talk about what 4E did to the Realms though. ;)

I myself have never ran or played in a true Megadungeon, but I did inherit a 1st edition AD&D mega-dungeon set of cards.

The first 'section' is 35 rooms, and the second 'section' is a sprawling 74 room crypt.

It was these cards that initially fueled my desire to play D&D, and provided a huge amount if inspiration in my early teens for my writing.

THIS is so amazingly boss! My dad had a small metal card file with index cards in it as well. They had information on monsters (some from the Monster Manual, some he had home-brewed up), locations, magic items, all kinds of stuff from his campaign. Like you, flipping through this was what initially got me interested in Dungeons & Dragons. Have an upvote. Have a tip. Seeing this made my day!

That's so cool that your intro was similar to mine! Thanks for the tip too! Glad these brought a smile to your face and a good memory.

The old School rules side of the RPG culture is going back to dungeons as the basis for an adventure.

Congratulations @modernzorker! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDo not miss the last post from @hivebuzz: