Introduction

Experiments are among the only few ways left to know anything for sure or atleast get insurmountable evidence and or insane insights. All of these is simply because experiments carry out tests and make findings based on watching and experiencing a case study do what it does. Way more reliable than mere thoughts and untested opinions.

On going around reading non-fiction books where writers are trying to make their points like the book Originals: How Non-conformists Move the World by Adam Grant, Outliers: The Story of Success by Malcolm Gladwell, etc; one would come to find that they report and talk about a lot of experiments carried out by psychologists, they use them to show you what has been found through experiments and how these findings prove the point they're trying to make.

Some of the Most Interesting Experiments Carried Out By Psychologists and Scientists would be a series of posts reporting these experiments to you so you can benefit by learning some of the things the expert scientists now know for sure or atleast have evidence for and or insane insight. So welcome to the

Sixth Edition! 🎊

For this edition, I'll be reporting some experiments from Malcolm Gladwell's 2005 book Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. Enjoy!

1

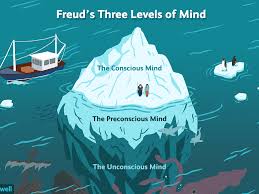

How we Learn Unconsciously

In page 17 of the book, Gladwell reports:

Imagine that I were to ask you to play a very simple gambling game. In front of you are four decks of cards — two of them red and the other two blue. Each card in those four decks either wins you a sum of money or costs you some money, and your job is to turn over cards from any of the decks, one at a time, in such a way that maximizes your winnings. What you don’t know at the beginning, however, is that the red decks are a minefield. The rewards are high, but when you lose on the red cards, you lose a lot. Actually, you can win only by taking cards

from the blue decks, which offer a nice steady diet of $50 payouts and modest penalties. The question is how long will it

take you to figure this out?

A group of scientists at the University of Iowa did this experiment a few years ago, and what they found is that after we’ve turned over about fifty cards, most of us start to develop a hunch about what’s going on. We don’t know why we prefer the blue decks, but we’re pretty sure at that point that they are a better bet. After turning over about eighty cards, most of us have figured out the game and can explain exactly why the first

two decks are such a bad idea. That much is straightforward. We have some experiences. We think them through. We develop a theory. And then finally we put two and two together. That’s the way learning works.

But the Iowa scientists did something else, and this is where the strange part of the experiment begins. They hooked each

gambler up to a machine that measured the activity of the sweat glands below the skin in the palms of their hands. Like most of our sweat glands, those in our palms respond to stress as well as temperature — which is why we get clammy hands when we are nervous. What the Iowa scientists found is that gamblers started generating stress responses to the red decks by the tenth card, forty cards before they were able to say that

they had a hunch about what was wrong with those two decks. More important, right around the time their palms started sweating, their behavior began to change as well. They started favoring the blue cards and taking fewer and fewer cards from

the red decks. In other words, the gamblers figured the game out before they realized they had figured the game out: they began making the necessary adjustments long before they were consciously aware of what adjustments they were supposed to

be making.

2

We Can Make Great Decisions Unconsciously the Same Way We Make them Consciously

Whenever we meet someone for the first time, whenever we interview someone for a job, whenever we react to a new idea, whenever we’re faced with making a decision quickly and under stress, we use that second part of our brain. How long, for

example, did it take you, when you were in college, to decide how good a teacher your professor was? A class? Two classes? A semester? The psychologist Nalini Ambady once gave students three ten-second videotapes of a teacher — with the sound

turned off — and found they had no difficulty at all coming up with a rating of the teacher’s effectiveness. Then Ambady cut the clips back to five seconds, and the ratings were the same. They were remarkably consistent even when she showed the

students just two seconds of videotape. Then Ambady compared those snap judgments of teacher effectiveness with evaluations of those same professors made by their students after a full semester of classes, and she found that they were also essentially the same. A person watching a silent two-second

video clip of a teacher he or she has never met will reach conclusions about how good that teacher is that are very similar to those of a student who has sat in the teacher’s class for an entire semester. That’s the power of our adaptive unconscious.

3

The Way We Keep Our Rooms/Houses is a Surprisingly Deep Peek into Our Personalities.

In page 50 of the book, Gladwell reports:

Gosling began his experiment by doing a personality workup on eighty college students. For this, he used what is called the

Big Five Inventory, a highly respected, multi-item questionnaire that measures people across five dimensions:

- Extraversion. Are you sociable or retiring? Fun-loving or reserved?

- Agreeableness. Are you trusting or suspicious? Helpful or

uncooperative? - Conscientiousness. Are you organized or disorganized? Selfdisciplined or weak willed?

- Emotional stability. Are you worried or calm? Insecure or

secure? - Openness to new experiences. Are you imaginative or downto-earth? Independent or conforming?

Then Gosling had close friends of those eighty students fill out the same questionnaire.

When our friends rank us on the Big Five, Gosling wanted to know, how closely do they come to the truth? The answer is, not surprisingly, that our friends can describe us fairly accurately. They have a thick slice of experience with us, and that translates to a real sense of who we are. Then Gosling

repeated the process, but this time he didn’t call on close friends. He used total strangers who had never even met the students they were judging. All they saw were their dorm

rooms. He gave his raters clipboards and told them they had fifteen minutes to look around and answer a series of very basic

questions about the occupant of the room: On a scale of 1 to 5, does the inhabitant of this room seem to be the kind of person

who is talkative? Tends to find fault with others? Does a thorough job? Is original? Is reserved? Is helpful and unselfish with others? And so on. “I was trying to study everyday impressions,” Gosling says. “So I was quite careful not to tell my subjects what to do. I just said, ‘Here is your questionnaire.

Go into the room and drink it in.’ I was just trying to look at intuitive judgment processes.”

How did they do? The dorm room observers weren’t nearly as good as friends in measuring extraversion. If you want to

know how animated and talkative and outgoing someone is, clearly, you have to meet him or her in person. The friends also

did slightly better than the dorm room visitors at accurately estimating agreeableness — how helpful and trusting someone is. I think that also makes sense. But on the remaining three traits of the Big Five, the strangers with the clipboards came out on top. They were more accurate at measuring conscientiousness, and they were much more accurate at predicting both the students’ emotional stability and their openness to new experiences. On balance, then, the strangers ended up doing a much better job. What this suggests is that it is quite possible for people who have never met us and who have spent only twenty minutes thinking about us to come to a

better understanding of who we are than people who have known us for years. Forget the endless “getting to know” meetings and lunches, then. If you want to get a good idea of whether I’d make a good employee, drop by my house one day and take a look around.

• (Find the first edition here)

• The second here

• The Third

• The fourth

• And the Fifth

--

Roll with @nevies, I run a Humor, deeper thoughts and sex talk blog here on Hive🌚

Donate/Tip:

BTC: bc1qlpu8rqftnn9r78dajpzf9p0ueqkvzdvzeayrtd

ETH:0x7168800F3b7499A2dd32B4C8Ae0EFA0F68A93800

LTC: ltc1qx0r3nym5hpq6mxvfkl3dzs2ap455aefh9rjq07

Email: [email protected].

Posted with STEMGeeks