Passwords are one of the most common forms of authentication to confirm the identity of a user. As they provide the key to access accounts and services, it is fundamental to choose them carefully so that they cannot be easily guessed. In other words, a password must be robust - something that an attacker could not easily guess, or identify just by having a computer performing repeated attempts.

It has already been discussed how passwords can be kept safe online in a previous article: that is only half of the story because, before getting there, they have to be created, and that involves a faulty component: the user. And because of that, most passwords are insecure.

Common mistakes that make a weak password

It's already out there. Human beings are creative, but tend to reason like... humans. When it's time to choose a password, the starting point is likely going to be a word, and all words have one thing in common - they are listed in big, comprehensive dictionaries. No matter which one is being chosen, it's already written in a list; and besides words in all different languages, lists of known passwords are out there for anyone to grab, for free. Hackers have all the lists of all the words plus some: given a database of protected passwords (which hackers are very good at obtaining), all it takes to crack them is to find how they are encoded (easy) and then try all the words in the dictionary until a match is found (which computers do very, very quickly).

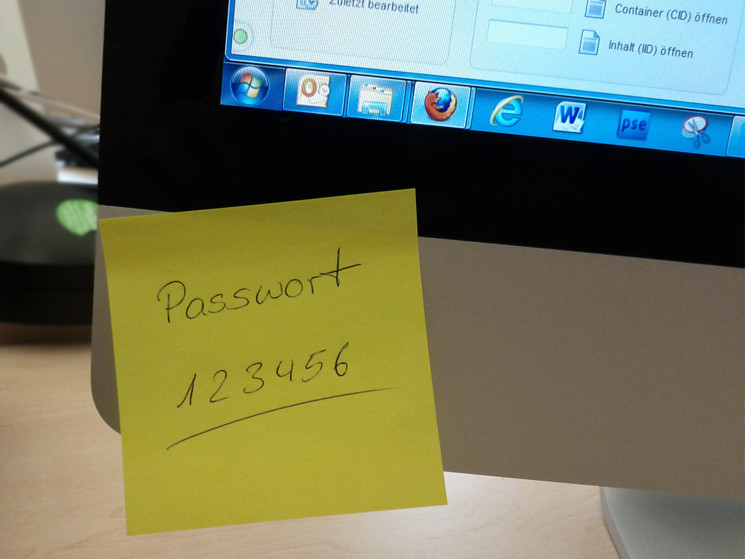

It's predictable. According to the 2019 survey published by security auditor SplashData, in a surprisingly high amount of cases, the password that protects digital identity, personal communications, and privacy of individuals is likely something like "password". Or perhaps "qwerty", or "123456789". One may think these are incredibly stupid choices (hint: they are), and yet they are only the fourth, third, and second most common, based on the company’s analysis of millions of passwords leaked on the internet.

The most common password of all, top of the list across seven years of cumulative data, is "123456" (yes, even easier than entry number two) - and it's used by 23.2 million of internet account, while "123456789" was used by 7.7 million, according to the UK's National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC).

It's short. Chances are the chosen password is not "Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious", but something like "football", "freedom", and "123qwe" (respectively entry #36, #35 and #25 of the Most Common Passwords List mentioned above). They all have one thing in common: a brute force attack - trying all possible combinations of letters and numbers with no additional logic - will guess them in less than one second because they're too short. Besides the fact that they are also dictionary words as well as having a very small alphabet (only letters and numbers), which makes them even easier to crack.

At this point one can assume that avoiding trivial mistakes like the examples listed so far is easy, as people have been creating for decades some better passwords than these: 1234qwer can be guessed instantly, 4422E34B takes 60 seconds, but keywords with numbers and special characters that are almost impossible to remember, and even harder to guess - like NE0A3h!c - must be secure.

Unfortunately, that is false: NE0A3h!c can be cracked by brute force in less than 8 hours (source: https://howsecureismypassword.net/). Worse yet, most IT departments around the world would approve it and recommend their users to adopt the same approach when creating their own: a random combination of numbers, letters, and symbols as that's what makes "a very good password", and that happens for historic reasons.

Why everything you know about passwords is wrong

In 2003, a midlevel manager at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) named Bill Burr was tasked with writing recommendations to improve password security. Back then, dictionary and brute-force attacks were the major threat as it was already known that people are poor at achieving sufficient entropy to produce satisfactory passwords; Burr then decided to rely on Shannon's information theory to build a schema that would evaluate the approximate entropy of human-generated passwords, and find programmatic ways to improve it. His work was published in the infamous Appendix A of NIST Special Publication 800-63 (pages 46-54), aptly named "Estimating Password Entropy and Strength", which included these guidelines:

Consider a system that used:

• a minimum of 8 character passwords, selected by subscribers from an alphabet of 94 printable characters,

• required subscribers to include at least one upper case letter, one lower case letter, one number, and one special character, and;

• Used a dictionary to prevent subscribers from including common words and

prevented permutations of the username as a password.

If that looks familiar, it's because they established the de-facto baseline requirements for "secure password generation" for years to come; Appendix A also pointed out that requiring users to change passwords regularly and frequently would improve security, by reducing the likelihood of an attacker checking all possible permutations.

Unfortunately, all of that was ineffective and wrong.

Based on the recommendations above, for instance, one would choose an 8-character word (e.g. "antidote") and apply substitution to make sure it would include at least one upper case letter, one lower case letter, one number, and one special character. The result - something similar to "Antid0t&" - would then "meet the composition and dictionary rules for user-selected passwords" and deemed safe thanks to its higher entropy; as it is well known today, that will be cracked in around 4 hours by brute force (8 hours as confirmed by https://howsecureismypassword.net/ with a high likelihood of hitting the correct result in half the time required to exhaust the entire alphabet space), or almost immediately by a permutation engine with some basic substitution rules commonly used by password testers.

At the age of 72, in a 2017 interview to the Wall Street Journal Bill Burr admitted that he was not a security expert, his method did not provide a valid estimation, and his research mostly came from a white paper written in the 80s and unrelated to passwords or their usage on Web.

“Much of what I did I now regret.”

In the following article it will be analyzed why the original NIST recommendations were wrong, what are their consequences, and how they resulted in a sense of false security that affected everybody for 15 years.

(image source: Certgate)

Congratulations @lucabarbera! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDo not miss the last post from @hivebuzz:

Great post. I admit I'm guilty of doing this especially for accounts I don't care about. I usually use a password generator for the important stuff.

I will write about it in a future article but - spoiler alert: if the keyword is more than 16 characters long, it's acceptable.

More details will be revealed! 😉