It's a perfectly ordinary London morning for Henry Denby: a spot of breakfast, a flip through the newspaper, then out the front door to see his wife and children off before the chauffeur arrives to take him to work. Unfortunately for Henry, it's the last time his wife and children will see him alive. Stalking Denby from across the road, an assassin from the military wing of the Provisional Irish Republican Army raises an AK-47 and calmly opens fire. He escapes, leaving behind a screaming widow and her two now-fatherless children.

Denby's crime? He'd just returned to London after an eighteen-month stretch overseeing Long Kesh, a prison run by the British to house and detain those suspected of terrorist activity in Northern Ireland. The sixties have stopped swinging, and The Troubles are afoot.

Unwilling to allow Denby's murder to go unanswered, British intelligence has little to go on except the knowledge their target has returned to Ireland. Their hope now lies in Harry Brown, a long-serving military captain who specializes in undercover operations. Tapped by his government due to his Irish heritage, Harry is taken to a safe house and given a crash course in the geography, politics, and accent of the region he's to insinuate himself into in order to track the fugitive.

The scheme is completely mad -- everyone, including Harry, understands this -- but the longer Denby's killer remains at large, the chance of further political assassinations increases. Harry has, at best, three weeks to catch the unknown gunman. Any longer and the relatively weak cover story concocted for him will stop holding up. For Harry, getting caught will mean game over.

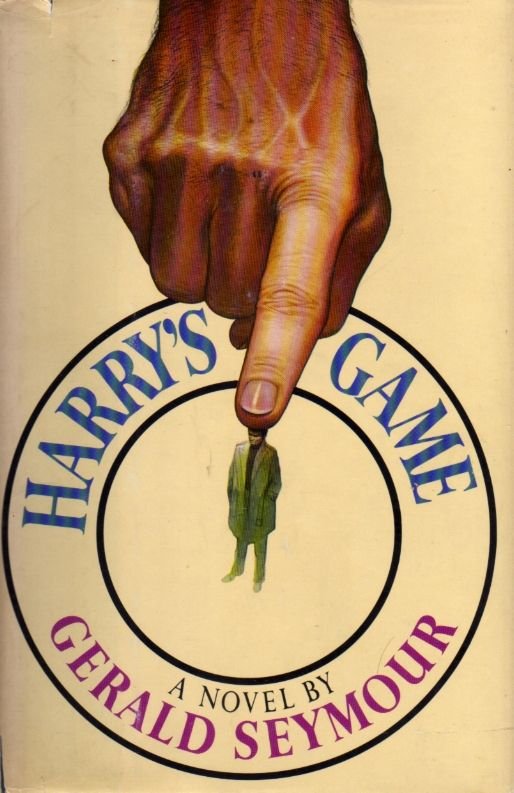

Holy shit, y'all: it's only June, but I've found my front-running candidate for best read of the year. Harry's Game is one of those first novels that you look at with seething jealousy, because it has no right to be as good as it is. Every page of it drips with authenticity. How is this author so intimately familiar with the situation, the politics, and the area?

Then you look into the author's background and suddenly it makes complete sense. Before he turned to writing full-time in the late 70's, Gerald Seymour worked as a journalist for ITV in the UK where he specialized in coverage of military and political violence. He reported on the war in Vietnam, covered the 1972 massacre at the Munich Olympics, spoke with the Baader–Meinhof Group in West Berlin, was on the ground during the Years of Lead socio-political turmoil in Italy, and (most apropos to this novel) spent time embedded in Northern Ireland during the start of The Troubles. Seymour knows it because he was literally telling the rest of the world about it on location.

What's most impressive about Harry's Game is how well Seymour represents all sides of the conflict. In most thrillers, there's a clear demarcation between the "good guy" and the "bad guy". This is, after all, the easiest way to tell the story. Look at Tom Clancy: Jack Ryan's the good guy working for the good guys in the US to bring down the Bad Guys of the Soviet Union, or the Eastern Bloc, or Japan, or whoever's threatening US soil this week. There's nothing wrong with that. Makes for fine, easy reading, doesn't it? Good guy shoots the bad guy, and we can all go home.

But Seymour isn't content to produce 'easy'. Yes, the extra-judicial murder of a political figure is obviously a heinous crime. Then again, so's detaining hundreds of Irish in the British equivalent of Guantanamo without trial. Just because Denby never personally abused someone housed there doesn't absolve him (or the British government, for that matter) of responsibility, and his killing is a vicious reminder of that. "One man's terorrist," Seymour has one character wryly note, "is another man's freedom fighter."

Speaking of our terrorist: we're introduced to him only as "The Man" in the book's opening pages. This nameless, faceless killer blends in with the rest of the early morning London foot traffic, shoots Denby, flees the scene, discards his weapon, and carries out a convoluted series of border crossings, followed by nighttime neighborhood hopping across Northern Ireland to prevent capture. His entire itinerary, from start to finish, has been plotted down to the minute. But while he obviously thinks of himself as a stone-cold killer, it doesn't take long for us to learn he's not the emotionless assassin he wants to be. He has a wife and children back home, and when he's gone away on a mission, their frayed nerves and fears are the price he pays for being good at what he does. We don't learn his name until almost halfway through the book; by the time we do, it's the last piece of the very humanizing puzzle Seymour has spent so many pages letting us put together, which is why I'm not revealing it.

And Harry Brown? Well, Harry's his mirror image: wife and children of his own, called away for long stretches on work he dares not discuss, leaving behind a family who greets every morning with the dread that today they'll receive the news he won't ever be returning home. And make no mistake, Harry's no saint. He's killed before, probably more times than The Man, and not in self defense, but because someone higher up the chain of command ordered it.

But there are more than two sides to this story. It isn't just Protestants and Catholics. Side three is the people who aren't directly involved in The Troubles, but merely trying to survive them. The innocents on the street. The men and women, captured and detained, frisked and humiliated, arrested and released, caught up in sweeps and nets cast wide, who see their friends and family abused by the British military. No matter how hard they try, neutrality is impossible to maintain. As one young woman comes to realize during the course of an interrogation, her life is forfeit either way. If she tells the police what they want to hear, the IRA will see her as a turncoat and kill her to set an example. If she withholds the information (which she never sought out, yet discovered anyway), then she spends what could be the rest of her life in a detention facility, subject to interrogation until she breaks, which brings her back to option one.

Side four is the rank-and-file members of the military, stationed in Northern Ireland because that's where the luck of the posting landed them. Mainly teenagers themselves, hated by the population they're ostensibly there to protect, frequent targets of thrown rocks and Molotov cocktails, shot by snipers while walking down streets, killed to "send a message" which always results in more crackdowns, which in turn result in more "messages" being sent. They're soldiers in an undeclared war, and it's clear their county is perfectly willing to sacrifice them.

Side five is Ireland herself: her streets, cities, towns, and countryside, carved into jagged-edged territories demarcated by miles of corrugated iron fencing, but united in the sounds of marching soldiers, breaking glass, and gunfire which no barriers can keep out. In Seymour's text, there's no sign of the Ireland of the tourist brochures and travel documentaries, the blue skies and poem-inspiring churches. There's only the war-torn hellscape of bombed out buildings, collapsed roofs, burnt lorries, and smashed windows. Seymour's atmosphere of urban guerrilla warfare is a character unto itself, forever lurking in the background, threatening all who come near.

But above all that, there's the tension, the "thrill" part of the thriller. Only in bad television does one single stunning revelation blow the case wide open. Instead, both sides are afflicted by a torturous death of a thousand cuts: a small piece of information let slip by someone innocently results in another thread plucked which threatens to unweave the whole tapestry. Both Harry and The Man are subject to dozens of these -- minor mistakes, none by itself sufficient to do lasting damage, but each one more pebble in an inevitable landslide that could bury them both.

If anything keeps you turning the pages in Harry's Game, it will be this. Watching Seymour laying the bricks and mortar, building up a plot we instinctively sense is not structurally sound enough to protect both men for long, is agonizingly delicious. This is a game for which a positive outcome is forever in doubt, and when Seymour strikes his climax and the jaws of the trap gnash shut, you're left with the feeling there's no other way it could have ended. The conclusion is disturbingly satisfactory in its unsatisfactory-ness, because no other end would be, even could be, appropriate, no matter how much we wish otherwise. The Troubles, after all, didn't reach their ostensible conclusion until the Good Friday Agreements were signed in 1998, while Harry's Game was published in 1975. Only in bad television does one man triumph over insurmountable odds and retire home in time to catch the final reading of the Shipping Forecast.

I am in awe of Gerald Seymour's cold, calculating assuredness of every aspect of this novel. To read Harry's Game is to receive a guided tour through history, a lesson in urban combat, and a first-hand look into the early days of a thirty year conflict which wasn't even a footnote in my education here in the United States. It's a brilliant realization of misery within the printed word, captivating and unrelenting in the way it tortures its reader as much as its characters. Top marks all around.

Harry's Game received a three-part television adaptation in 1982, where the Clannad song embedded above first appeared, though it showed up in 1992's Patriot Games, which also involved the IRA. To my knowledge, it's never been officially released in the US, although in Canada it was distributed on video under the title Belfast Assassin, and it's obviously available in the UK. As if that's not confusing enough, the three-part serial was later edited into a single two hour and ten minute feature which is missing around 30 minutes of footage, making it a less-optimal viewing experience. It makes some minor tweaks and changes from the book (including the ending), but otherwise remains reasonably faithful to the source material. Some of it was shot on location in Belfast and other areas of Ireland, which gives an extra sense of veritas since it was produced only seven years after the book's publication, and I recommend seeking it out even if you aren't interested in reading the novel.

Congratulations @modernzorker! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Your next target is to reach 72000 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPOh, man, you have got to watch '71 if you haven't seen it yet!

There is a side of me that wants to cheer the IRA, but the actual terrorism (political violence against civilians) dampens my support for their attacks against government agents like the incident you say opens this book.

I've never heard of it. Is it a film? TV series? Documentary? I would like to know more!

It's a film set in Ireland in 1971. A British soldier is separated from his squad during a riot and must survive the night. Gritty and dark. Lots of moral shades of grey.

I'm sold!