Good day Hivers and Book Clubbers,

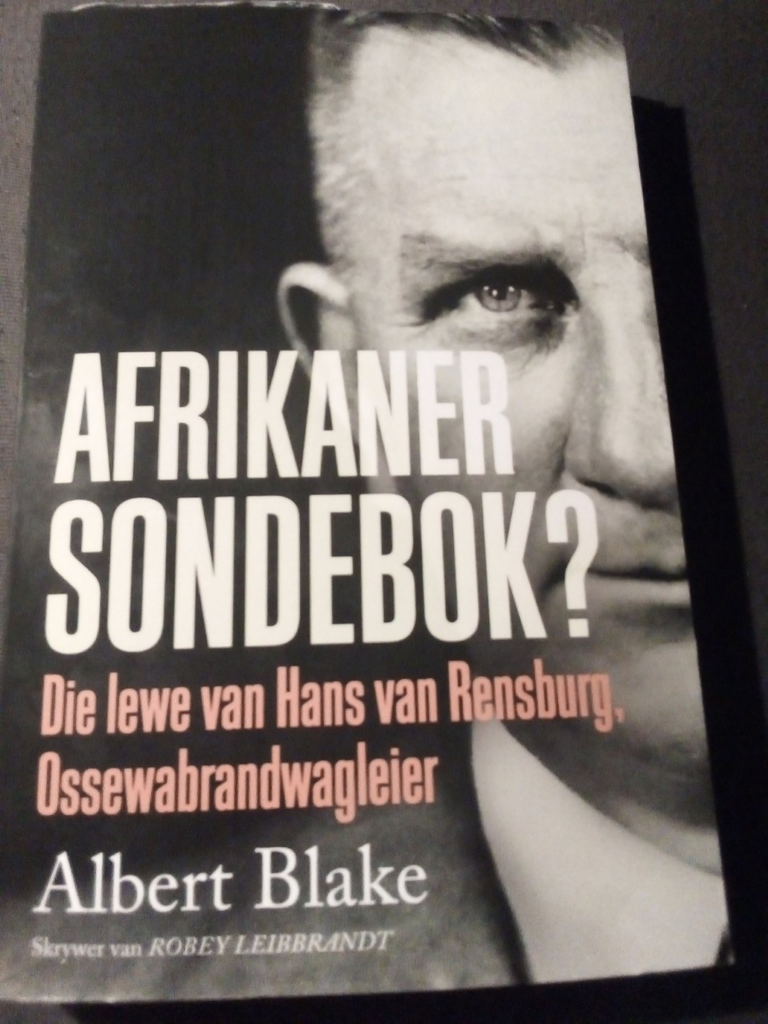

This the the third and final part of my review of 'Afrikaner Sondebok?' by Albert Blake, which is a biography of Hans van Rensburg, an important man in Afrikaner history.

Impact of WW2

We left the story in the previous part at the moment where Van Rensburg became leader of the Ossewabrandwag, an Afrikaner cultural organization, in january of 1941. For this, he gave up his position as administrator of the Free State to give it all his time and energy. The book notes he did not do it for the money, because the pay was far worse than in his original position, and he often lived in near-poverty in the late 40s and 50s.

Under his leadership, there was a clear shift in the style of the entire OB. It went from cultural to political, and from civilian to para-militaristic. These changes can clearly be traced to Van Rensburg; his pro-republican and anti-British stances, combined with his personal sympathy for national socialism, steered the organization towards an explicit pro-republicanism. It was the main end-goal of the OB: a republic of South-Africa, free from the British, and from party-politics.

Van Rensburg's fascination with the military was due to him being part of it. As mentioned in part one, he joined the commando near his home-town at age 16. He also was an avid hunter, and was slowly climbing the ranks of the South African army as well, albeit in more of a reserve-capacity. The militarism in the OB became clear in its parades and marches, which clearly took inspiration from Italy and Germany. It was also apparent in Van Rensburg's title as leader; 'Commandant General', and the main leaders also being called Generals.

The fate of the OB as an organization quickly became tied to that of Germany in the Second World War. When it looked like Germany was doing well, mainly in 1940 and 1941, the popularity of the OB rose to heights before unknown in South Africa; it is estimated that about 300.000 people were members at the time.

You can imagine that these numbers for a national socialist organization caught the attention of basically everyone in the country. Smuts' United Party government kept a close eye on all main leaders of the OB, Van Rensburg chiefly among them. Some advised Smuts to imprison Van Rensburg, but Smuts never did during the entire war. Also, the OB was clearly a threat , in terms of popularity and allegiance, to other nationalist groups, more specifically the National Party.

There were many disputes between the NP and OB; about whether and how the latter should tackle party politics. At some points van Rensburg wanted to enter party politics, despite his lack of belief in the system. This was thorougly opposed by the NP, who feared splitting the Afrikaner electorate, thus letting Smuts' UP win in perpetuity. Also, the NP's leader, D.F. Malan, and Van Rensburg did not get along very well on a personal level, which hindered cooperation, obviously.

Sabotage and Treason

South Africa was heavily divided on whether it should enter World War 2. Smuts' United party was split too. Smuts and the English South Africans were all for helping out the United Kingdom and joining. Hertzog, the Boer general who had joined the UP in 1933, was against it, along with a significant part of the Afrikaner wing of the party. The National Party was clearly opposed, seeing it as a conflict Afrikaners had no stake in at all.

Afrikaner resistance to WW1 caused the 1914-Rebellion. For WW2, no such active revolt occurred, though political resistance was more severe. The OB, clearly sympathising with the German cause, and against that of the British Empire, took to other forms of resistance. Sabotage became very common in South Africa; telephone lines were cut, power stations destroyed and bridges/railways were blown up.

Van Rensburg led the people who did this, the Stormjaers (Storm troopers), and knew about and had a final say on all their activities. There was one rule, however: no Afrikaner lives should be lost because of the sabotage-actions. A principle that prevented an active revolt, at the very least.

Another important factor in the OB's resistance was the contact that was established early on between Van Rensburg and the Germans. Through Lourenzo Marques (Mozambique, then held by neutral Portugal) Van Rensburg sent intel to the Germans on several things; South African troop movements, Allied ships docked in South Africa, etc. The Germans, in turn, sent several plans to Van Rensburg for the OB to stage a coup in South Africa, and for van Rensburg to rule it as a type of client-state for Germany. Deemed far too risky and reckless by Van Rensburg, he declined all offers to do so.

Later Life

As the war went on, the Germans were clearly starting to lose from 1943 onwards (some would argue earlier, but lets stick with this). The OB's fate was bound with Germany's chances, it seemed, because it entered a steep decline at the same time as German chances in the war faded. After the war ended with the loss of Germany, the OB's national socialist tendencies faded fast. It had another big issue; many inside the South African government were looking to try Van Rensburg in court for treason. The evidence compiled against him was mounting, and he would probably be judged guilty if a trial was called.

But this did not happen; Smuts was never willing to pull that trigger. This, once again, had clear political reason. He was not looking to make martyrs out of Afrikaner nationalists while nationalism was on the rise among Afrikaners. Also, Van Rensburg himself was not nearly as influential as he had been several years prior; the problem had, in a way, sorted itself out.

Smuts' UP government would not be able to stem the tide of Afrikaner nationalism; in 1948, the National Party won a victory against the UP, meaning Smuts' exit out of politics, and a realization of some of Van Rensburgs' ideals. For one, the new cabinet was all-Afrikaner and Afrikaans-speaking; a first in South-African history. It also put South-Africa on the path of becoming a republic, which happened in 1961.

Van Rensburg would die of a heart attack in 1966, at age 68. The book relays several other aspects of his life that I left out of this review; his marriage, his passion for fishing and hunting, and several details that can be talked about in a 300-page book, that won't make it into a review. I hope I've convinced/interested you in picking up this book; it's also available in English on sites like Amazon, so it shouldn't be an issue. I'll see you al in a next review on another book. Until the next one,

-Pieter Nijmeijer

Your content has been voted as a part of Encouragement program. Keep up the good work!

Use Ecency daily to boost your growth on platform!

Support Ecency

Vote for new Proposal

Delegate HP and earn more