The same day went Jesus out of the house, and sat by the sea side.

And great multitudes were gathered together unto him, so that he went into a ship, and sat; and the whole multitude stood on the shore.

And he spake many things unto them in parables, saying, Behold, a sower went forth to sow;

And when he sowed, some seeds fell by the way side, and the fowls came and devoured them up:

Some fell upon stony places, where they had not much earth: and forthwith they sprung up, because they had no deepness of earth:

And when the sun was up, they were scorched; and because they had no root, they withered away.

And some fell among thorns; and the thorns sprung up, and choked them:

But other fell into good ground, and brought forth fruit, some an hundredfold, some sixtyfold, some thirtyfold.

Who hath ears to hear, let him hear.

Matthew 13:1-9, King James Version

We live in a hyperreal society.

Fresh philosopher Jean Baudrillard uses the term hyperreality to express the inability of the consciousness to distinguish between reality and a simulation of reality. Fact and fiction are blurred together. The questions of truth and origins fall to the wayside. There is merely what is perceived to be real, seen through the lens of the eternal now.

Nowhere is this more evident than in modern entertainment. Pick up a Pop Cult tale and you know what you're in for. Strong Female Characters who can do everything better than their male counterparts. Minority representation in every aspect except in the villain's role. LGBTQ+ ideology in children's media. Diversity, Inclusion and Equity uber alles. The story doesn't matter, the characters don't matter, they are merely the wrapping around the core messaging.

The human brain is hardwired for pattern recognition. Once you see something that fits the pattern, you get a dopamine hit. When you observe the latest entry in your favourite series, you get the dopamine hit. As you read the work, the dopamine continues to flow, as you explore the new material in the familiar setting. When you see the latest instalment of a franchise that was part of your formative years, you get another dopamine hit in the form of nostalgia.

Recognizing this, the Pop Cult chooses existing franchises to parasitise. In them, they will find a ready audience, primed to flock to the nearest offering. The Pop Cult takes charge of the franchise and pumps out new offerings. They promise the same setting, the same mechanics, the same characters—just updated for the modern day. And by that, of course, they mean that they hollow out everything that made the franchise great and replace it with their poisonous ideology. They do not care about petty things like art and craft, except where it suits the purpose of promoting propaganda. When they consume the work, this legion of superfans experience the twin drives of nostalgia and novelty, and the reward mechanism rewires their brain to accept the messaging.

Those who refuse the messaging are treated as heretics and castigated in public. It is a human desire to avoid pain and scandal, and so the superfans either go along with the messaging or quit altogether. Over a long enough timeline, the only people who flock to the series are those already primed to consume the ideology of the Pop Cult—and not a work for its own sake.

The pursuit of hyperreality is create a false reality to replace reality. It is the consumption of illusion, in a bid to make the false a new truth. For this campaign to succeed, the high priests of the Pop Cult demand that every consoomer treat the Pop Cult products as reflections of reality. Through the propagation of Current Year, they seek to create Year Zero, a brave new world founded on pure ideology and nothing more. This is evangelism as entertainment—and badly made evangelism at that.

It doesn't matter who started it. Everyone in the Pop Cult is doing it now. They are all engaged in the great work of fabricating a hyperreality to replace reality.

Fiction outside the Pop Cult isn't much better.

The world of publishing is a cutthroat world. At the end of this sentence, there is a new story, a new author, a new series. The market is over-saturated with content, and little context with which to sift through everything. Audiences are less likely to take a chance on an unknown author. Indie stories might be cheap, but the time and energy invested in reading a story is not. Average readers would rather read more of the authors they love, and authors similar enough to the authors they love.

Complicating matters is that modern-day audiences have plenty of entertainment choices. TV shows, movies, games, all of them reasonably cheap, highly accessible and—more importantly—much easier to consume than a book. Why, then, would they want to read a book?

For some authors, the answer is that the book they are offering is similar to the non-reading entertainments the reader already know. Thus the rise of gamelit / LitRPG, which mechanics similar to video games and tabletop games. Thus the cinematic writing style, with highly stylized visuals—and nothing but visuals, with no forays into character thoughts or even their remaining senses. Thus the writers who make nonstop references to modern pop culture, in a bid to swiftly forge a connection.

The economic realities of self-publishing thus push authors into the same direction. Pick a selection of best-selling authors and you will see them using the same techniques. They pick a hot and hungry genre. They write stories in line with genre conventions, employing all the tropes readers are used to seeing. They tap into nostalgia using pop culture references to create and reinforce a reader connection.

The stories are all fungible. They employ the same tropes, story beats, themes, ideas, just expressed differently. The plots may be different, the characters may be different, the worldbuilding may be different, but the stories are all the same interchangeable goop. The only real way to distinguish between them is the level of craft the authors put into the work—and, as a quick perusal of the Amazon bestseller list can tell you, you don't need craftsmanship to hit the bestseller list, only marketing ability.

All this leads to a narrowing—a dumbing down—of the fiction field. The marker of quality is simply how well an author can vomit tropes and pop culture references on the page in a semi-logical fashion; linguistic and artistic skills are secondary. Fantasy used to be explorations of exotic places and cultures; now, every character talks, thinks and acts like a Current Year American—or a modern-day Japanese, for the specific genre of isekai fiction. Science fiction used to dive into the impact of technology on humanity; now it is simply about how much high-tech gadgetry you can cram into a story that resembles other sci fi stories. Thrillers displayed the skills and the mindset of professionals who run at the cutting edge of violence; today they are all about Hollywood-style action scenes. The desire for awe and wonder has become the desire for more of the same, just different.

This is another kind of hyperreality, no less insidious for its apparently apolitical nature. It is a dumbing down of the field, it is a deliberate rejection of the canon that created the culture it draws from, and at its worst, it is a second layer of hyperreality built upon the hyperreality of Current Year. It is the idiocracy unfolding before your eyes, it is the Rand's second-handers ascendant, it is turning away from the stars dotting an infinite universe to kiss the mud beneath the jackboot.

How did we get here? And how do we get out?

The study of semiotics is the study of signs and meaning making. A sign is anything that communicates an idea, and that idea is called meaning. In Simulacra and Simulation, Baudrillard describes four stages of progression from sign to simulacra.

The first is the sacramental order. The sign is a faithful copy, a reflection of reality.

The second is the order of maleficence. The sign does not faithfully reflect reality, rather hints at the existence of a deeper reality that the sign itself cannot communicate. The sign perverts and masks reality.

The third is the order of sorcery. The sign now claims to represent something real, but there is no actual representation. It claims to be a copy, but it has no original. Meaning is conjured out of thin air, communicated by the sign, to appear as a reference to the truth. The sign now masks an absence of reality.

The fourth is pure simulation. The sign bears no resemblance to reality whatsoever. Signs reflect other signs which reflect other signs unto infinitum. Signs no longer pretend to be real, because existence has become so artificial that any claims to reality are expected to be phrased in hyperreal terms.

The world of fiction is the world of pure simulation. The Pop Cult seeks to replace reality with its hyperreality. Through its embrace and portrayal of woke ideology, it has convinced consoomers that Wokeism is the new reality. Modern fiction anchors itself in that hyperreality, bound together by an incestuous network of never-ending references and trope-fests. Fiction reflects other fiction reflecting other fiction, a wilderness of mirrors forever reflecting the same hunk of bland goop at some central point no one can reach.

Why should you care about such high-flown concepts as hyperreality and post-modernism? What does it matter if the world of fiction has become so artificial? Consumers get their dopamine hits, creators get their dollars, and life chugs on. Why should anyone care?

Because there is a huge cost to departure from reality.

The backlash against the woke set, against the hyperreality they have created, is ongoing. We're not quite at the levels of Go Woke and Get Broke, but high-profile franchises that push woke ideology are reporting massive losses month after month. They have nothing going for them but wokeism, and now they are being scorched.

When the hyperreality collapses, so too does everything that is anchored on that set of beliefs. Lacking roots, they wither away. You can see this in Big Name authors reporting pathetic sales figures, such as Zoe Quinn and former Science Fiction Writers of America President Cat Rambo.

Non-woke authors who have embraced the hyperreal aren't likely to be spared either. Those that make Pop Cult references grounded in the present will find their stories sorely dated three to five years from now, or even one year. Soon they will encounter an audience that has either ignorant of those references, or actively despises them. Their works are the equivalent of junk food, to be consumed once and forgotten forever.

Those who choose the hyperreal have no deepness of earth. They may be ascendant today, but they will be forgotten tomorrow. For those of us who seek more than just the hyperreal, we must plant our works upon good ground.

Writing is truth. This is the position I have held since I put pen to paper. Whether you write fiction or non-fiction, the goal is to communicate truth. The purpose of fiction is to smuggle higher truths past the dragons of the imagination. Through counterfactual worlds, science fiction and fantasy points at a deeper reality. Thus, writers must return to tradition, return to the sacramental order.

Looking at my own genre of cultivation fiction, we can see the four stages of simulacrum:

The first stage is the manuals left behind by the sages who have obtained enlightenment. The manuals describe the methods the sages used, and so reflect the highest level of reality.

The second stage is the rise of the wuxia and xianxia genres. Drawing inspiration from shallow knowledge of the manuals, the authors reference cultivation methods to justify the supernatural powers present in the stories, and how characters attain and grow their power. Yet by focusing on power, not enlightenment, their portrayal of cultivation perverts and masks the essential reality.

The third stage is the internationalisation of the genre. Western authors dutifully copy the tropes of wuxia and xianxia stories, including cultivation, with no understanding whatsoever of Chinese culture and philosophy. They simply use those tropes to explain away the fantastical elements of the story, without knowing or caring how or why those powers emerge in the first place, or even the culture from which these trops arise. This is the stage of the absence of reality.

The fourth stage is the present day. Wuxia, xianxia, cultivation and progression authors constantly copying and reflecting each other, freely using the tropes and idioms and terminology without a care. The genre has become entirely artificial, rooted in nothing more than conventions and customs.

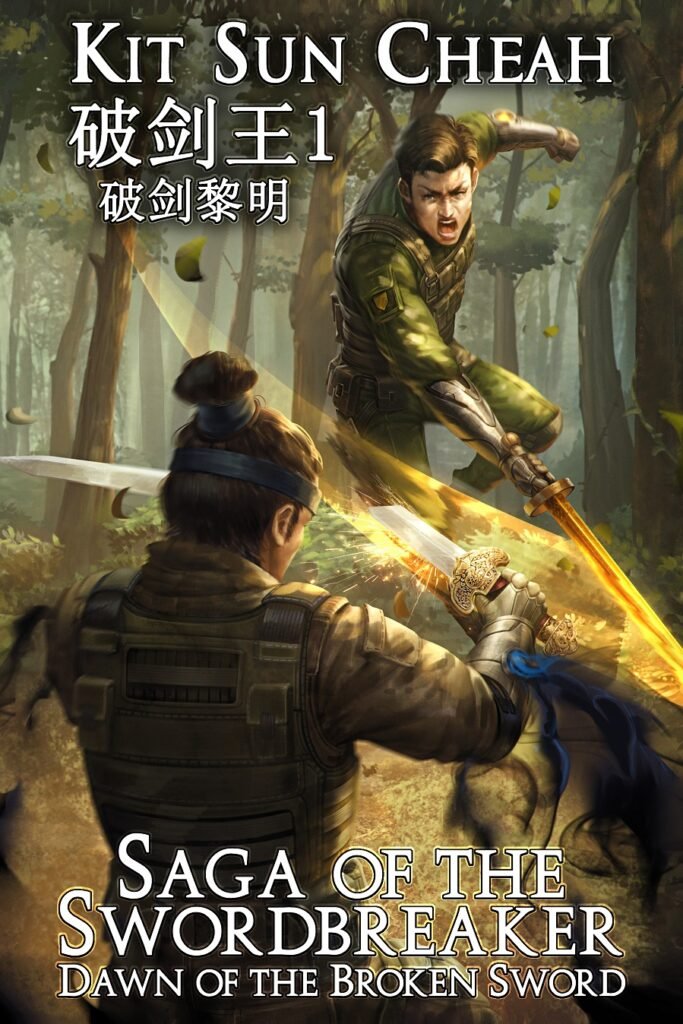

Saga of the Swordbreaker returns to the wellspring of the genre. The cultivation methods in the series are taken from real-world practices. The in-story society practice cultivation to chase power, fame and fortune, but some characters choose the original purpose of pursuing enlightenment. This is the core conflict and meta-conflict of the series: reality versus hyperreality.

Writers in other genres could do well by returning to the source. The genesis of Western fantasy is the Bible and European fairy tales. The basis of the thriller is the thin red line of trained, strong and disciplined men standing between civilization and chaos. The romance story is rooted in the desire for pair bonding and domestic happiness. Plant the seeds of your stories in good soil, and watch them bear fruit.

It is an arduous task. Those who choose this path are going against those who rule the zeitgeist. Yet there is no choice. They are making war against reality itself. Either you fight back or you'll be folded into a world of illusion.

The cracks in this world of illusion are already showing. People are already turning away. Soon there will be opportunities to reach out to a crowd that is tired of the hyperreal. You have to position yourself to take advantage of it before those opportunities arise.

When there are many masters, it is difficult to distinguish yourself. But in a time of no masters, it is easy to stand out. We are rapidly reaching the time of no masters. When the hyperreal falls apart, only those who choose reality will be left standing.

Dawn of the Broken Sword, Book 1 of Saga of the Swordbreaker, is on sale for just $0.99 until 22 June. Check it out here!