*This is a sum up about Absolutism in Portugal, with a great number of source materials in english since there is almost no material like that on Hive or i dare say in th internet... I will post some sources but can't promise i will go down to list every single one, there are to many of them on some events that inspire one topic with 12 words, on this case i pass on referring the source or it would make this task impossible.

Most of it was offline material like old books, dictionaries and encyclopaedias, i will still post the most info i can on the bibliography at the end of the post. I will also be editing this articles if i get new books or sources, plus linking words to future posts on this board for convenience of the reader

Some names, term for titles and antique words i could not find proper translation, words like Condestável,fronteiro and other terms associated with the suffix -Mor-, and many other examples like this i only write in the old Portuguese form *

ABSOLUTISM IN PORTUGAL

Absolutism can be defined as the "system of government in which the power of the sovereign is absolute, not subject to any control" (Le Petit Robert). Absolute, here, in the etymological sense of independent, complete, integral, total, not admitting any exception, restriction, or reservation. There is no doubt that, in Portugal, from the late 15th century until the liberal revolution of 1820 (and, especially, from the late 17th century onwards), the monarchs held all the attributes of sovereignty - the power to make laws, administer supreme justice, collect taxes in their name, appoint officials, maintain a standing army (since the mid-17th century). It is important to note, however, that in practice, absolute monarchy was limited in its action in different ways, depending on the circumstances, certainly due to the survival of political bodies (corts, the king's council, councils) and traditional legal bases (the law of nations, which guaranteed property, customs, and privileges, moral laws), as well as structural reasons: communication difficulties, which persisted throughout the existence of the Old Regime society and hindered the action of royal officials (Corregidors, judges, etc.).

In other words: if absolute monarchs simultaneously held the legislative, executive, and judicial powers at the highest level, the truth is that the exercise of their power had to face social and regional resistances, stronger or weaker depending on the circumstances and the social forces at play (for example, during the reigns of D. João II or in the time of Pombal), both from sectors of the privileged classes (nobility and clergy) and from popular sectors (small merchants, peasants, etc). Although current historiography has produced some essays that address various aspects of the modern state from different perspectives, we lack partial and analytical studies on social classes, their participation in central administration bodies, and the internal opposition that certain social layers conjecturally opposed to state policy; on the evolution of political and ideological apparatuses, the career of officials, the ideology underlying the exercise of political power, and its intervention in civil society. There is still a scarcity of monographs on the theorists of absolutism, and for many of them, we only find more or less general references. I will limit myself here to outline the current state of the questions, focusing fundamentally on the political-institutional and social structures, relating them to economic and financial structures. In the current state of research, it is still difficult to establish a rigorous periodization for the process of construction and development of the absolute state in Portugal.

However, we can roughly outline the major phases of its evolution without setting too rigid chronological limits from the outset. Everything naturally depends on the criteria used in this periodization. Thus, for example, Jorge de Macedo, based on a strictly political criterion - the supreme organs of the State - distinguishes four phases in Portuguese absolutism. The proposed periodization naturally derives from the very notion of absolutism that he adopts. Perry Anderson, on the other hand, believes that the periodization of the modern state should be sought in the changing relationship between the nobility and the monarchy and the concomitant political shifts that were its correlation.

In his view, the absolute state essentially represents the interests of the feudal nobility, although the means it uses to defend property and aristocratic privileges can simultaneously "secure the basic interests of emerging merchant and manufacturing classes." Opting for this criterion of a markedly sociological nature (but which, in part, ignores the financial foundations on which the State is based), we must always take into account the complex relationship between the crown and the nobility, or factions of the nobility, since this social order does not always behave the same way as a whole (it is enough to remember that it is divided at decisive moments like Alfarrobeira, at the beginning of the reign of D. João II, or during the Restoration).

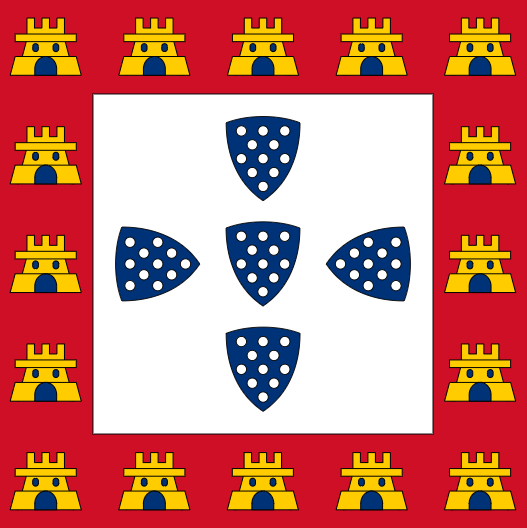

D. João II also known by the nickname "The Perfect Prince"

However, to substantiate a rigorous classification of the modern state in its path, we cannot only rely on a single criterion: it is important to look for other variables, not just of an exclusively political or social nature, including the origins of state revenue and their relative weight (the collected revenues partly condition the structure of the State itself) and, on the other hand, how these incomes are spent (which part is redistributed to the landowning classes, unproductively, and which part is invested in economic development activities); the economic policy pursued (especially regarding land ownership, trade, and industry) may be another factor not to be disregarded in a diachronic characterization of absolutism (for example, to what extent does land policy reinforce or weaken the survivals of the feudal mode of production). Without the concern to establish rigid and unworkable chronological barriers, it is possible, however, to briefly characterize four major phases through which the evolution of the Portuguese modern state passed, undergoing profound changes and assuming different forms, depending on the structural shifts that occurred in the Empire and Portuguese society of the Old Regime. In addition to these four phases, we also address an initial period - from the 1383-1385 revolution to the reign of D. João II - in which the foundations of the absolute state are built. This is precisely where we begin this general perspective.

During this period, there is a process of reconstitution of the nobility, marked by the creation of great lordships linked to the royal family - the Duchies of Coimbra, Viseu, Beja, and Bragança granted, respectively, to the infantes D. Pedro, D. Henrique, D. Fernando, and D. Afonso - by the promotion of elements from lower nobility and the bourgeoisie, and by the institution of entailments, according to the Mental Law. At the same time, there is a progressive complexification of the Royal Household, with the king's vassals occupying the main political, administrative, and military positions in the State, which tend to increase in number. If the Battle of Alfarrobeira (1449), with the defeat of the faction of Infante D. Pedro, corresponds to a temporary turning point in overseas policy and in the trend towards the concentration of political power, the reign of Afonso V (1446-1479), in which many members of the nobility are granted immense donations and numerous titles (twenty-two new titles), also represents a remarkable moment in the process of administrative centralization, where the high aristocracy is called upon to organize itself within the state apparatus, occupying military (fronteiro-mor, Condestável, marechal do Reino, etc.), political, and administrative positions (chancellor-mor, scrivener of purity, regent of justice, overseers of the treasury, etc.).

There are frequent cases of concentration of more than one state office in the hands of a single figure (for example, the 1st Baron of Alvito, a legalist, accumulates the functions of chancellor-mor, scrivener of purity, and regent of justice; the Count of Vila Nova de Portimão was governor of the Kingdom and regent of justice). The correlation of political power tends to create new inequalities, at the expense of the higher nobility, in favor of new elements promoted to high administrative functions, in what is traditionally called the "squires' regime" (Albuquerque, 1944). One must bear in mind that many of these high officials were given important territorial and judicial jurisdictions, which consolidated their social and economic power. At the same time, the development of the King's Household also involves a growing number of officials, a reflection of the expansion of the Empire.

D. João II and the novel interventionist strategy of the crown. Under the reign of D. João II (1481-1495), it is noticeable that the social composition of the high administrative staff is changing, with the predominance of elements promoted by the king from lower nobility and new socio-economic elites. The measures taken by D. João II to control the nobility are quite known: the transfer of the chancery to Lisbon (1476), the reform of the Council, and the promotion of elements from outside the highest aristocracy. On the other hand, the king's fiscal policy is also known, based on the control of the collection of traditional taxes and the systematic search for new sources of income (systematic exploitation of royal domains, customs increase, reorganization of the tax system).

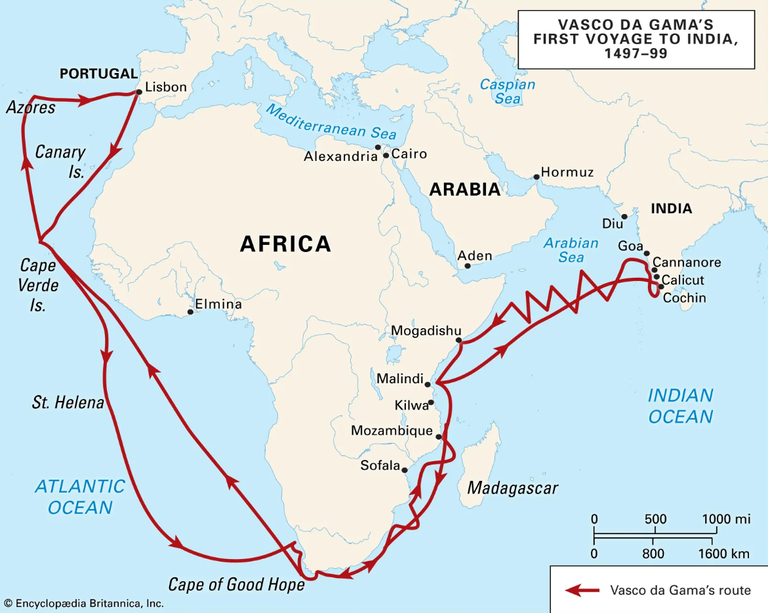

The progressive concentration of power in the hands of the sovereign, in this context, is also reflected in foreign policy, marked by a search for greater centralization in relation to the feudal lords of the African and Asian overseas territories. However, the process of territorial consolidation and the centralization of state powers meet strong resistance from the major noble families, led by the old factions linked to the Dukes of Braganza and Viseu, who are fighting for the possession of the throne, thus protecting their interests. The victory of D. Manuel (1495-1521), linked to the Duke of Beja, in the context of the crisis caused by the discovery of the route to India by Vasco da Gama (1498), allows the nobility to regain a significant share of the state apparatus. The building of the modern state, in its dual aspect - on the one hand, increasing centralization and the professionalization of state apparatuses, on the other hand, the concession of fiefs to members of the highest aristocracy - continues, even after the monarch ascends the throne, with the conquest of Ceuta (1415) and the beginning of overseas expansion (1418-1419), marked by the introduction of new forms of recruitment and organization of forces for the conquest of new territories.

The state system (whether on the Portuguese mainland, the Atlantic archipelagos, or the Maghreb) is made up of a varied political-administrative apparatus, whose structures of military and civil administration change according to the characteristics of the occupied territories and the needs of local powers. It is important to point out that, in many cases, the local administration and justice are autonomous or are in the hands of the locals themselves (principle of the incorporation of local laws). The "Royal House" or the "kingdoms" are the two main regional units (or provinces) within which the Portuguese state is territorially divided. In practice, this subdivision corresponds to the military occupation or possession of territories. If the Royal House of Lisbon, the core of the monarchy, is governed by high administrative officials, the Kingdoms, organized in similar ways, are governed by representatives appointed by the king, with the consent of the local powers.

The end of the schism of the Western Church in 1417 (Council of Constance) allows Pope Martin V (1417-1431) to launch a new crusade, initiated by the Portuguese in the Atlantic archipelagos. Simultaneously, internal disorders in the kingdom of Fez facilitate the conquest of Ceuta, a veritable international staging area for the Portuguese. On August 14, 1415, the Portuguese troops, under the command of D. João I (1385-1433), start the siege of Ceuta, which falls into their hands on August 22, opening the doors to the Maghreb, the Orient, and India. The conquest of Ceuta mobilizes the cooperation of all sectors of society (with the notable exception of the cities of the kingdom, which, at this time, are strongly divided and facing serious internal problems). Although the conquest of Ceuta marks the consolidation of the dynasty's power, its extraordinary expansionist trajectory is far from over. As Krus rightly points out, it is precisely this aspect that distinguishes Portuguese expansion from other European powers: it was not the fruit of a "global policy" or a "well-considered plan," but the result of "a kind of dynamic," of an "internal logic" that "carried away" the country in "a whirlwind of conquests and discoveries" (Krus, 1978, 173-74). If it is true that "the conquests of Portugal are not due to the genius of a few men, nor to the king's purpose, nor to a political or military concept, but to the natural course of the monarchy's expansion, to a strange destiny," it is also true that these conquests were marked by phases, occasional crises, setbacks, and changes in orientation. The latter is particularly marked by the conquest of Ceuta, in the sense of the emergence of a new international political factor. As António Vieira writes, "the king got the Ceuta he wanted, but Ceuta wasn't the one he expected."

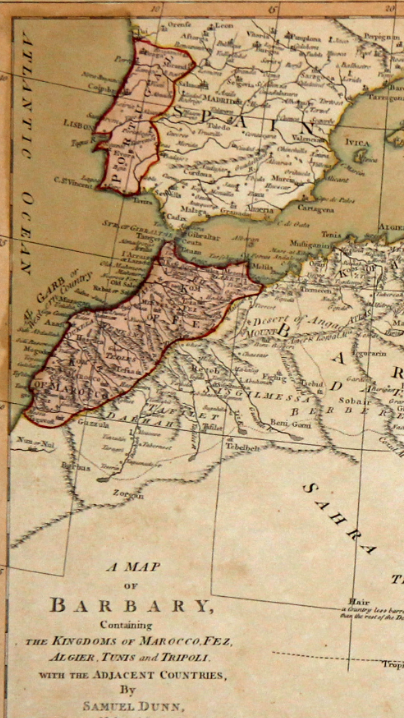

Ceuta is not a secondary enclave in a territorial extension of the state; it is a point of passage between the Maghreb, Spain, and the Portuguese Atlantic archipelagos. In practice, Ceuta becomes a problem for Portuguese foreign policy. The problem of Ceuta's administration reveals the difficulties faced by the Portuguese to establish an effective control over their territorial possessions, which were increasingly distant and difficult to maintain, as they advanced into the Moroccan territory. In this period, the beginning of the conquest of the Canary Islands also plays a prominent role. As an Aljamiado manuscript (a Romance language written in Arabic characters) from the end of the 15th century testifies, the Portuguese began their expansion in the islands in 1424, with the occupation of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, and El Hierro. The occupation of these islands takes place within a context of great international tension, in the wake of the Iberian Crusades, waged in various parts of the Maghreb. By the Treaty of Windsor (1386), Portugal and England, in the face of the threat from the Maghreb, agree to a pact of mutual assistance. In addition to securing Portuguese aid in the event of a Castilian attack, John of Aviz (1385-1433) guarantees Henry IV of England that his brother, D. Duarte, the Duke of Coimbra (1433-1438), would marry a Portuguese princess to consolidate the alliance. To strengthen the bonds, Portugal grants some Englishmen, established in the Azores, exclusive trade rights with Portugal and the entire Azorean archipelago. The Englishmen install themselves in Terceira and Faial, starting the colonization of the archipelago, exporting livestock and other products to England. The occupation of the Canaries takes place within this context. The occupation of these islands allows Portugal to secure maritime access to the Canary archipelago and the Kingdom of Granada and, at the same time, to gain military and strategic control of the Moroccan coast.

The conquest of the Canaries is not just a product of the advance of the Portuguese crown, but a result of the alliance with the English. This explains the strong English presence in the Azores and other parts of the Portuguese archipelago. The Canaries operation is, therefore, more a result of the initiative of the English merchants than the Portuguese crown itself, which, as far as we know, only sent two caravels, one from Lisbon and the other from Madeira, to support the occupation of the islands. The English actions, aimed at conquering the Canaries and taking over the Cape of Ghir, make the situation increasingly difficult for Portugal, which is becoming increasingly dependent on its foreign allies.

The crisis of 1415, which divides the Portuguese state, creates the ideal conditions for the expansion of the Portuguese. 1415 is the year of the conquest of Ceuta, but it is also the year of the death of the first queen of Portugal, D. Filipa de Lencastre, the same year in which her husband, D. João I (1385-1433), is seriously ill. In this context, a war of succession begins, opposing the Duke of Beja, D. Fernando (1402-1443), a bastard son of the king, and the Duke of Viseu, D. Henrique (1394-1460), the king's younger brother. Although the Dukes of Braganza (D. Afonso, 1377-1461, and D. Fernando, 1403-1478) initially supported D. Henrique's claim, they soon switched to the side of the Duke of Beja. The war will last until 1438 and end with the execution of D. Fernando and the definitive defeat of the Duke of Beja. The war of 1415 is a significant moment in the history of Portuguese expansion, revealing the deep divisions in the kingdom and the difficulties faced by the crown in its attempts to establish an effective control over its possessions in the Maghreb.

D. João II (1481-1495) and the war with Castile (1475-1479): the conquest of Guinea and the advance in the Atlantic. Although the Portuguese occupation of Ceuta was not without problems and financial difficulties, its strategic importance justified the maintenance of the outpost. In fact, Ceuta serves as a key element in Portuguese expansion, enabling the country to maintain its influence in North Africa and the Maghreb, which have become increasingly important for the Portuguese. This explains why the occupation of Ceuta was one of the most costly and traumatic of all the military actions carried out by the Portuguese crown. The Portuguese presence in North Africa, by helping the Kingdom of Granada in its resistance to Castilian aggression, also explains the close ties between the crown and the rulers of Granada (the Nasrid Dynasty). With the fall of Granada in 1492, the Portuguese abandon their positions in Morocco and withdraw to Ceuta.

The Kingdom of Fez (Morocco) is, in the first half of the 15th century, a melting pot of Maghreb, Mediterranean, Atlantic, and even oriental influences. These influences are deeply rooted in the economic and political reality of the time, in the wake of the Almohad collapse (1147) and the rise of the Kingdom of Fez (1250-1465), during which the kingdom experienced a process of territorial expansion, the consolidation of its political structures, and the promotion of an intense cultural and economic activity. The Kingdom of Fez is formed by a multiplicity of heterogeneous territories, occupied by different populations (Berbers, Arabs, Jews, and Christians), with different legal systems (Malikite, Ibadite, and Mozarab) and different languages (Berber, Arabic, Mozarab, Spanish, Hebrew, Ladino, and Portuguese). The Kingdom is a crossroads of exchanges between different regions and a complex administrative, economic, political, and legal structure, which corresponded to a multiplicity of lords, powers, and interests. In Fez, the Portuguese face significant resistance from the local population, divided into tribes, clans, and factions. The Portuguese are also faced with opposition from the local elites and local rulers. The fall of Ceuta and the establishment of the Fez domain in Portugal create a completely new political and military situation. Portugal is no longer able to defend its territorial possessions, as it does not have the means to maintain its military presence in Morocco, and its allies, the English, are increasingly reluctant to support it. The Portuguese have to withdraw from Ceuta (in 1443), and their presence in North Africa becomes a major concern for the crown.

At the same time, Portuguese expansion advances further into the Atlantic, with the exploration of the western coast of Africa. This phase of expansion is marked by the advance along the West African coast, seeking access to the sources of gold and other valuable resources. In this context, the reign of D. João II (1481-1495) stands out, with the intensification of exploration and the conquest of Guinea. The Portuguese advance into Africa is closely linked to the colonization of the Azorean and Madeiran archipelagos, which provide valuable stopover points for maritime navigation. The first phase of overseas expansion involves a vast program of settlement of the archipelagos, whose colonization starts around 1430. The colonization of the islands is seen as a fundamental step in the development of Portuguese expansion, providing the country with valuable resources and strategic points for the conquest of new territories.

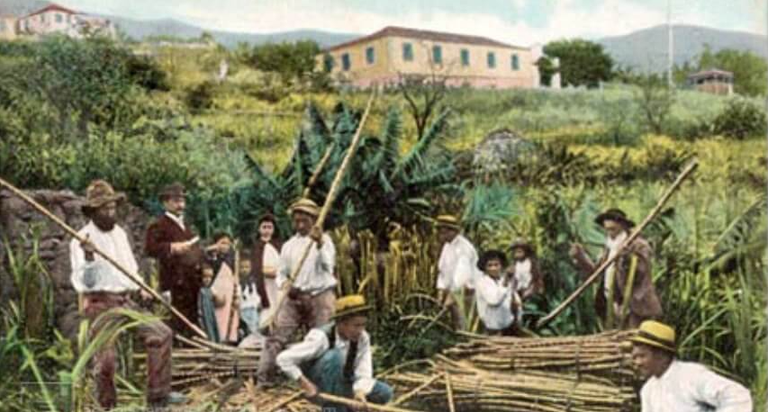

The colonization of the Azorean and Madeiran archipelagos is a collective enterprise involving a variety of social groups and interests. The process begins with the occupation of Madeira (1418-1419) and the Azores (1427-1432), following the island model established in the Atlantic archipelagos. Madeira is the first colony founded by the Portuguese overseas (1418-1419), after the conquest of Ceuta (1415). The island is colonized by Portuguese settlers from different regions of the kingdom, who receive lands and titles in exchange for their military and economic support. The colonization of Madeira is organized by the crown, which grants lands to the settlers and establishes a system of land grants (Captaincies) similar to the one used in the colonization of the Azores. The settlers who participated in the colonization of Madeira were not just members of the nobility, but also commoners, many of them from the lower ranks of the nobility and the bourgeoisie. The establishment of settlements in Madeira allows Portugal to secure control over the island and develop its economic resources, particularly sugar production.

The Portuguese settlers also establish contacts with the local population, which includes a significant number of Christians and Jews. The colonization of Madeira represents a significant step in the development of Portuguese expansion, providing the country with valuable resources and strategic points for the conquest of new territories. The success of Madeira's colonization encourages the Portuguese to expand further into the Atlantic, leading to the exploration and settlement of the Azorean archipelago. The colonization of the Azores, which begins around 1427, follows a similar pattern to that of Madeira, with settlers receiving land grants from the crown in exchange for their support in the colonization effort. The Azores become a crucial stopover point for Portuguese navigation, providing a base for further exploration and conquests. The colonization of the Azores also involves various social groups, including members of the nobility, commoners, and even prisoners who are granted freedom in exchange for their participation in the colonization effort (Gaspar Frutuoso, 1873, 51-53).

The expansion of Portuguese colonization in the Atlantic archipelagos is closely linked to the search for new sources of wealth and the desire to establish strategic points for further exploration. The success of these early colonization efforts sets the stage for the next phase of overseas expansion, which involves the exploration of the African coast and the conquest of Guinea. Under the reign of D. João II, Portugal intensifies its efforts to explore the African coast, seeking access to the sources of gold and other valuable resources. The Portuguese establish a series of trading posts and fortifications along the coast, gradually extending their control southward. One of the key objectives of Portuguese exploration in this period is to reach the region known as Guinea, which is believed to be a source of gold and other valuable commodities. The conquest of Guinea represents a major achievement in Portuguese overseas expansion and contributes to the country's growing wealth and influence. The Portuguese also establish trade relations with local African rulers, exchanging European goods for African products, such as gold, ivory, and slaves. The exploration of the African coast and the conquest of Guinea mark a significant phase in Portuguese expansion, setting the stage for further exploration and conquests in Africa and beyond.

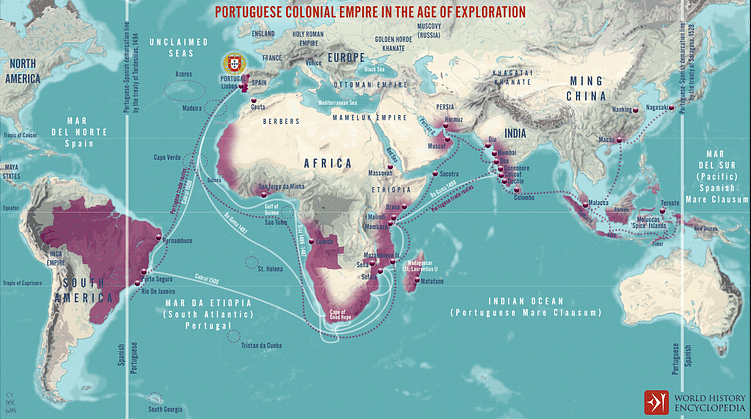

The reign of D. João II (1481-1495) is characterized by a strong focus on overseas expansion and exploration, with the goal of establishing Portugal as a major maritime and colonial power. The king takes a personal interest in exploration and navigation, sponsoring expeditions along the African coast and supporting the work of navigators and explorers. Under his leadership, Portugal makes significant advances in its exploration of Africa, pushing further south and establishing a network of trading posts and fortifications. D. João II also encourages the search for a sea route to India, which ultimately leads to Vasco da Gama's historic voyage in 1498. The king's policies and initiatives contribute to Portugal's emergence as a dominant player in the Age of Exploration, with a global empire that spans from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. The reign of D. João II represents a pivotal moment in Portuguese history, marking the transition from the early phase of overseas expansion to the establishment of a vast colonial empire. The exploration and conquest of Guinea, as well as the pursuit of a sea route to India, are key achievements of this period, setting the stage for Portugal's future as a major colonial power.

It is important to note that the expansion of Portuguese overseas territories and influence also had significant economic and social repercussions within the country. The influx of wealth from overseas territories, including gold, spices, and other valuable commodities, contributed to the growth of Portugal's economy and the enrichment of its ruling classes. At the same time, the slave trade, which was an integral part of Portuguese overseas expansion, had a profound impact on African societies and contributed to the emergence of the transatlantic slave trade. These economic and social dynamics are essential aspects of the history of Portuguese expansion and its consequences. Additionally, the establishment of Portuguese colonies in Africa, Asia, and the Americas led to cultural exchanges, the spread of Christianity, and the blending of different cultures and traditions, shaping the cultural and social landscape of both Portugal and its overseas territories.

In conclusion, the period of Portuguese overseas expansion, from the late 15th century onwards, represents a complex and multifaceted historical phenomenon that encompasses exploration, conquest, colonization, trade, cultural exchanges, and economic transformations. The achievements and consequences of this expansion continue to be subjects of historical study and reflection, shedding light on the interconnectedness of different regions and societies in the early modern era.

Bibl:

Perry Anderson, El estado absolutista, 4º edition. Madrid, Siglo Veintiuno

G. Durand, Etars et Institutions XVI-XVIII siècles, Paris

A. Colin, 1969; F. Hartung e R. Mousnier, «Problèmes concernant la monarchie absolue», Rome;

?. Sousa, 1987;

Actes du X° Congrés International des Sciences Historiques, 1. IV, 1955;

Krus, 1978 (several quotes);

H. Lapeyre, Les monerchies européennes du XVI° siècle, Paris, PUF, 1967;

Mann, 2007, 200-201;

Sobre Portugal: Martim de Albuquerque, O Poder Político do Renascimento

Porturies, Lisboa, ISCSU, Universidade Técnica, 1968;

Gaspar Frutuoso, 1873;

Eduardo de O. França, «O poder real em Portugal e as origens do absolutismo», História da Civilização Antiga e Medieval, n.° 6, Universidade de São Paulo, bol. LXVIII, Sao Paulo, 1946; Vitorino M. Godinho, Ensaios II, 2.° edition, Lisbon;

Lopes, 1961, 170-171;

Sá da Costa, 1978 (incluindo «A evolução dos complexos histórico-geográficos» and « Finanças públicas e estrutura do Estado», from "Dicionário de História de Portugal" by J. Serrão, in vol. I, Lisbon, 1963;

Tavares, 1985, Page 22-23;

Aubert, 1960, Page 51;

Magalhães Godinho, 1944;

I was most certainly not expecting a history lesson when I saw that you had posted! Well written and informative. Very interesting to learn about the four-phase evolution. It's also really cool that hive allows this type of history to be permanently recorded.

I liked that you pointed out that 'absolute' power is never actually absolute. There are some modern-day thinkers (Hoppe maybe chief among them), who talk about the virtues of monarchy. In brief, because the king's family owns the land, their incentives are aligned with the people for long-term growth (compare that to having a new leader every 8 years). Hoppe's defense against tyrannical kings was that their family members (and the other nobility) would often assassinate would-be tyrants.

Not saying that Hoppe is right or that you have to necessarily agree with him, just that a few sections of your write-up reminded me of those points.

Nicely done!

This idea was patent after reading several authors it is not something i came up with myself

I dont know Hoppe will look into it, i think that monarchy can have some good points, the ones you talk about and more, imho the king will have 0 reason to be corrupt, the current republic format is made of many weak and pathetic people many times i wish we had a supreme commander instead of some whores of power 4 years at a time...

Thank you for stopping by brother! I appreciate it not easy to grow a new topic from nothing!