English spelling is a mess. A complete and utter mess. Pronunciation and spelling are completely divorced at this point and only have a passing relationship thanks to rules that have arisen over the years to somewhat make sense of the chaos. But as these rules are descriptive and not prescriptive, they only hold true about half of the time; the rest of the time we are left completely in the dark and unless we are in a position to hear a word being pronounced, we will have no idea how to say it ourselves from the written word; and, if we are trying to transcribe one we hear, God help us.

I'm sure most of us know the problem. Sometime in the latter 1500s, spelling started to become fixed thanks to the appearance of written dictionaries that were made possible as a result of the printing press. This was all well and good, but it had the unfortunate timing of happening during the latter part of the Great Vowel Shift, which changed the way we pronounce all the vowels—moving from how they are pronounced in many European languages to what they are now—and with them almost all our words. The Great Vowel Shift had started earlier, but was still happening as spelling started to be standardized, therefore many older pronunciations became the proper way to spell a word even as those pronunciations were very rapidly changing. Suddenly we had a written language that didn't match our spoken language, and the problem has only gotten worse since.

There were other issues that made this modern mess. School teachers in the 1600s and 1700s liked to add extra letters to words under the mistaken belief that linking English words to Latin and Greek would make the language more pure. So we got things like det becoming debt to link it with the Latin word debitum, iland becoming island to link it with the Latin insula from which they mistakenly thought it came from, and ake becoming ache because of the mistaken belief that it came from the Greek akhos. And on and on it went.

Add in loanwords, which we don't even try to reform when we adopt, but usually retain both the spelling and pronunciation of the place the word is from, and English becomes the absolute mess it is today.

Enter spelling reform. This is not a new idea. Various teachers and grammarians had been suggesting it for years. Famed inventor Benjamin Franklin not only proposed many spelling reforms, but also proposed adding new letters to the alphabet. This makes more sense than you might think. Consider that English has about 13 vowels in most dialects (up to 20 for Received Pronunciation) yet we only have 5 letters we use to represent these vowels. Unfortunately, Franklin's proposals were ignored.

It wasn't until (at least in American English) Noah Webster in the early 1800s that we got positive change that stuck. Webster is the reason Americans don't use u's in our colo(u)rs, why we flipped our re's in words like theater, and why we no longer double our l's in words like canceled. He had more changes that weren't accepted. For example, he proposed tongue be written tung. Phonetically that makes perfect sense, but it proved a bridge too far for early Americans who ignored that particular spelling change.

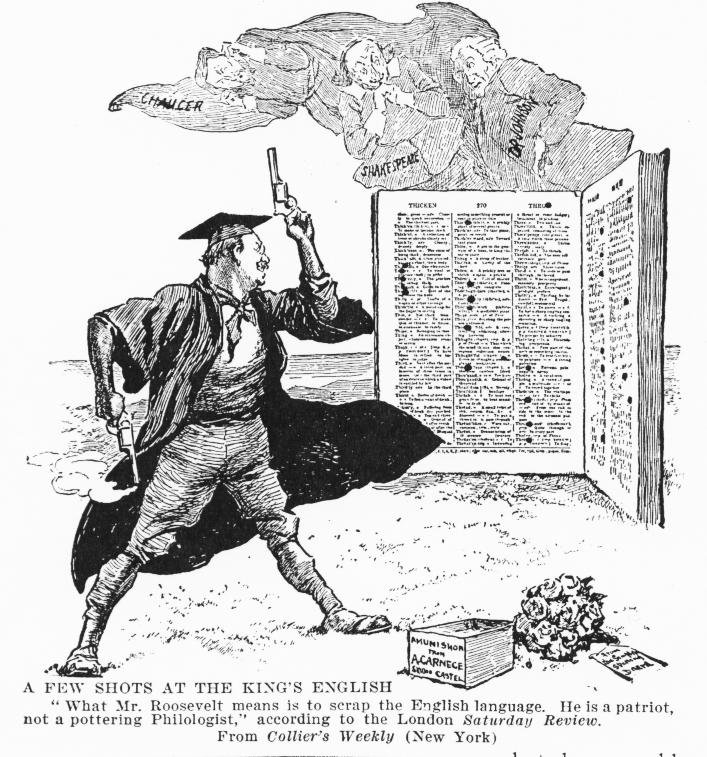

Many years later there was another push for spelling reform. The Chicago Tribune jumped on this one. As did people like Andrew Carnegie, Mark Twain, and President Theodore Roosevelt who ordered the government to immediately use the new spellings. This is where we get words like donut instead of doughnut, catalog instead of catalogue, and so on. This proposal also gave us less successful changes like tho, altho, thru, and nite. These last few have stuck around in casual writing, but they are no longer considered proper. In fact, Congress gave TR the middle finger by reversing his order that the government use the new spellings just a few months later and instead required the government to use the old spellings. (You see, even 100 years ago the government was fighting about pointless things)

In the years since there have been stabs here and there at other spelling reforms, but none have had any real success, except maybe in casual writing. Across the pond from America, the UK has also had their share of attempted spelling reforms. George Bernard Shaw, for example, was a huge proponent of spelling reform (like Franklin, he also wanted to reform the entire alphabet in addition to spelling).

The common arguments against reform are:

- It will make old literature inaccessible

- It will make etymology more difficult

- It looks weird (i.e. "Change is bad")

Common arguments for:

- It makes the language easier to learn for children and immigrants.

- It improves spelling for everyone (When words are spelled as they are pronounced, they become much easier to spell properly)

There are other arguments both for and against, but I want to keep things simple. Although just to play devil's advocate against the inaccessible argument: consider the long s (ſ) which is no longer used, but was for a long time, up until the mid 1800s. This trips up students today a lot when they go back and try to read things like Paradise Lost (printed "Paradiſe Loſt") or even the US Constitution ("...in order to form a more perfect Union, eſtabliſh Juſtice, inſure domeſtic Tranquility..."). Does the spelling with this old letter render all old writing inaccessible? Maybe some, but for important documents there exists many modern copies that update the spelling, which kind of shows that the argument of old literature becoming inaccessible is nonsense since things will be reprinted and updated.

Anyway, spelling reform has been successful in many other languages, but English remains stubbornly resistant to the idea. With the exception of Webster, and a very few of the Chicago Tribune proposals, and random chances here and there since (for example, phantasy becoming fantasy, probably due to the popularity of Tolkien—he was responsible for changing the popular spelling of "dwarfs" to "dwarves" too, among others) we've never had any real reform success.

These days many people seem of the opinion that English has grown too big to reform. It is now the world language for better or worse, so we'd not only have to get one country to agree to a reform but all countries. That might be true, but... is it? When blogs were more popular, many casual spellings (thru/tho, etc) became more common. Now with text messages we have all kind of new spellings happening. U get me, bro?

I don't know. I fully support spelling reform and would love if some group tried to take this on in a more systematic way. I'd love to see the language spelled in a way that makes more sense and that makes it easier for foreigners to learn.

But what do you think? I'd love to hear your reasoning for or against.

❦

|

David LaSpina is an American photographer and translator lost in Japan, trying to capture the beauty of this country one photo at a time and searching for the perfect haiku. He blogs here and at laspina.org. Write him on Twitter or Mastodon. |

I grew up immersed in the Appalachian English dialect, which is not quite to the level of Mandarin/Cantonese communications breakdown but it's not too far behind it. That experience makes me suspect that any spelling reform is doomed to die a death by dialect. Even if you somehow manage to standardize it, it's just going to immediately start diverging again in dozens of different directions.

I don't know if local dialects are the reason it wouldn't work. But major dialects—as in UK English, US English, India English, etc—would probably be the sticking point. Small differences, like a u in some words or using "jumper" or "sweater" are just curiosities, but if each major dialect started spelling completely differently, it could quickly make a mess. Well, an even bigger mess than we already have.

Yeah, I don't expect it to ever happen. This is more just a thought experiment.

👍 !PGM

The idea of reforming English spelling to make it easier is appealing, but it could also make old writings harder to understand and disconnect words from their origins. It's a tricky debate with valid points on both sides.

Yep, this is true.

Yeah my friend

The intracacies of language are fascinating for me, especially as one considers that for example in Italy, the movie Gomorrah which was based in Naples and filmed in the local dialect, had to be translated for the rest of the people in Italy into textbook spoken Italian because the dialect was so strong. Subtitles in Italian for an Italian movie!

The same happens in English - depending where you are you get very different accents and pronunciation of words and even spelling. I do not favour the weird U in words like the Brit’s do but how to change it is a challenge for sure.