Chapter 3.3. Blockchain innovation and the EU project going forward

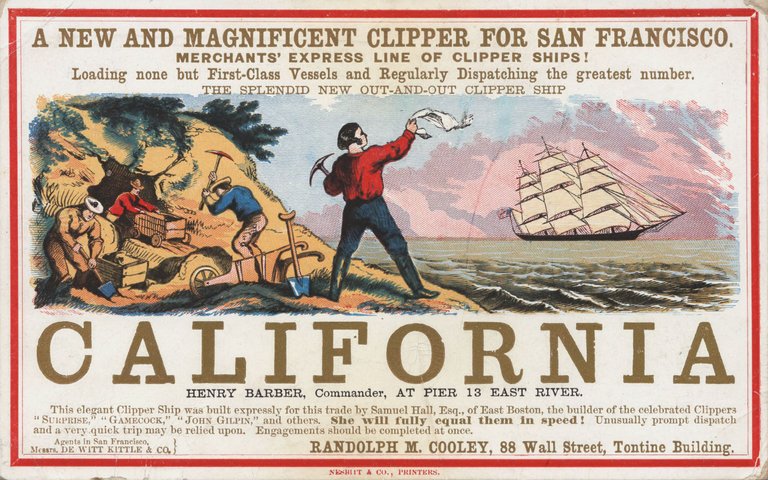

-60. Bitcoin, without which we wouldn’t be discussing MiCA today, is often called “digital gold” and the process of creating blocks for its “proof of work” blockchain is even called “mining”. During the Californian gold rush of 1848 many people came to California in the hope of making a fortune. Only a handful did so, and among them most did not mine nor pan for gold, but rather met the needs of the miners, by selling shovels, pickaxes and, like Levi Strauss, working pants (known today as “jeans”).

-61. I have analysed MiCA in Part 2 and one observation stands out: despite its stated objective of “supporting innovation” (see section 2.2.1), MiCA appears not as much concerned with the “gold” of innovation, nor with the innovative “gold miners” (the aspiring entrepreneurs ready to risk it all in order to build the “Google of crypto-assets” in Europe), as with making sure that there is demand for the “gold” – by legitimising the crypto-assets, as explained in chapter 3.1, thus transforming the Union into a market for them, and ensuring that traditional financial firms are in a good position to make a fortune by selling “shovels and pickaxes” (crypto-asset services) to would-be “gold miners”, as explained in chapter 3.2. In this context, I’ve considered the likelihood of this approach leading to the invention of new types of “shovels”, “pickaxes” and “jeans”.

-62. That leaves open several questions: who will be the 'gold diggers'? Are they going to come? And are they going to find significant amounts of “gold” to sell, so that the new “gold rush” does not turn into a mere “flash in the pan”?

"To sell shovels, you need capital either inherited or through banking connections" (source)

"To sell shovels, you need capital either inherited or through banking connections" (source)

3.3.1. MiCA brings no specific solution to blockchain-specific legal challenges

-63. It is uncontested that blockchain and crypto-asset systems raise new legal challenges, starting with the difficulty of attributing legal responsibility in the context of a community of anonymous, voluntary participants who avoid the “legal person” status on purpose. MiCA approaches this specific challenge the way Alexander the Great is said to have solved the Gordian knot: by prohibiting new Bitcoin- and Ethereum-inspired crypto assets from being admitted to trading on a European trading platform or offered to the public, unless the European CASP itself assumes the legal responsibility of complying with MiCA’s provisions (Recital (32) in the final version).

-64. A similarly blunt and indiscriminate approach is observed in relationship with blockchain systems’ ability to increase efficiency and decrease transaction costs by replacing trusted third parties with computer code, more specifically the “smart contracts” mentioned in Part 2, par. 100. I have noted at the end of Part 1 (par. 111), where I quoted a famous analysis by Lawrence Lessig, titled “Code is law” (written a decade before Bitcoin appeared) the paradigm change which blockchain-based smart contracts have enabled for the first time. The complexity of the situations which can arise has been illustrated for instance by the “TheDAO” hack from 2016 (discussed in section 3.1.1) where part of the blockchain community of “miners” took responsibility for upholding “the spirit of the smart contract” and rolled back the blockchain to prevent what was, intuitively, a felony, while the other part of the community decided to respect “the letter of the smart contract” and declined responsibility (thus leading to a “hard fork” and the apparition of the “Ethereum Classic” blockchain).

-65. As far as “legal certainty” is concerned, it is worth asking if MiCA should not have proposed an explicit position with respect to the distribution of legal responsibility between the (potentially anonymous) author of a vulnerable smart contract, the platform operators, and the users of that smart contract (among which the hacker himself must be counted).

-66. In MiCA’s explanatory memorandum, the Commission noted that “while some crypto-assets could fall within the scope of (existing) EU legislation, effectively applying it to these assets was not straightforward” (see Part 2, par. 22). One such category of crypto-assets is that of “governance tokens” which pose another technology-specific challenge. Governance tokens are not primarily intended as financial assets but rather as a tool allowing fine-grained accounting for the timely distribution of decision-making power inside an organization.

-67. Governance tokens give holders the right to make proposals and vote on existing proposals to evolve the underlying protocol. They bear similarities to voting shares in a company which entitle owners to express their position with respect to how the company is run. However, unlike shares, governance tokens are much more flexible and can come with as many or as few rights attached as their issuer’s imagination allows. They typically do not offer a claim on the issuer’s underlying assets nor do they automatically entitle the holders to a share of the profits of the issuer, but can offer other benefits (such as for instance discounts on, or preferential access to other crypto-asset related products and services. They might be transferable or not depending on various parameters and can be lent with all or only a subset of their attached rights, in a much more fluid, flexible and direct, peer-to-peer way than shares. Despite being well aware of the importance of good governance, as “governance arrangements” appears 16 times in the final version, MiCA is oblivious to the crypto-assets capacity to transform governance.

-68. The shortcomings and incongruities of MiCA’s approach to regulating crypto-assets and blockchain technology is also apparent in its dealing with specific aspects, whether with respect to legal obligations, market abuse, or detection and enforcement. MiCA’s Art. 75(5) on providing custody and administration of crypto-assets on behalf of clients, institutes an obligation for CASPs to provide a statement of positions “every three months”, while Art. 76(9) on operation of a trading platform for crypto-assets requests CASPs to make information available “during trading hours”, and this for markets in crypto-assets which routinely operate in real time on a continuous, “24/7” basis with no “trading hours” limitations.

-69. Title VII for instance, dedicated to competent authorities, EBA and ESMA details in its Art. 123, “General investigative powers” that EBA can “take or obtain certified copies” (1b) and “request records of telephone and data traffic” (1e) but does not make note of the power of distributed ledgers to provide accurate, unfalsifiable records which can be used in the course of investigations.

-70. Where reserve assets need to be audited, MiCA consistently relies on a trusted intermediary, without considering the ability of smart contracts to leverage the transparency of blockchains in order to produce automated “proof of reserves” which are faster, timelier, and more efficient, and which, by contrast, have been put forward by American legal scholars such as K. Werbach (see Part 2, par 44).

-71. A consistently blunt and indiscriminate approach is on display with respect to illicit finance, which in the opaque traditional financial world is dealt with through attempted prevention, at the expense of respect for private life and protection of personal data, although these are fundamental rights. Thus Art. 76(3) prevents “the admission to trading of crypto-assets that have an inbuilt anonymization function” such as Monero (XMR), implying that there can be no legitimate reasons for using a privacy-maintaining crypto-asset.

-72. In keeping with their ideological roots, crypto-assets are representative of a radically different approach, which puts respect for private life first and balances the needs of the social group through a combination of incentives to stay within the boundaries of socially acceptable behaviour, detection based on the transparency and immutability of the blockchain and, in some cases, reputations. As far as detection is concerned, specialized firms such as Chainalysis publish a “Crypto Crime Report” in order “to demonstrate the power of blockchains’ transparency – [with] estimates [which] aren’t possible in traditional finance.” They also provide tools which assign a form of reputation to otherwise anonymous blockchain addresses and are able to estimate a probability that a crypto-asset balance on a ledger is connected (or not) to illicit activities.

-73. On the basis of the previously quoted Recital (16) stating that “Any legislative act adopted in the field of crypto-assets should be […] founded on an incentive-based approach” it appears legitimate to expect that MiCA actual provisions would have avoided the traditional approach which ignores the specificities of the field it aims to regulate.

-74. There are several advantages to transposing existing regulations to the markets in crypto-assets in a straightforward manner, ignoring the specificities of the domain and avoiding addressing the unique legal challenges that it raises. First of all, it’s simpler and faster. Second, it uses approved legislation as template. Third, it makes both the task of the regulators and of the incumbent financial firms easier, as both are already prepared to take onboard the ensuing legal obligations.

-75. Take for instance MiCA’s Title VI “Prevention and prohibition of Market Abuse involving crypto-assets”. The initial Commission Proposal selects and transcribes five articles from the “Market Abuse Regulation” (MAR) that are generic and contain nothing specific to crypto-assets. The final version adds a sixth article (Art. 92) which contains more specific indications demanding that “any person professionally arranging or executing transactions in crypto-assets shall […] without delay report to the competent authority […] aspects of the functioning of the distributed ledger technology such as the consensus mechanism, where there might exist circumstances indicating that market abuse has been committed, is being committed or is likely to be committed.”

-76. This example illustrates once more the boilerplate quality of the initial Commission proposal and the value added by the ordinary legislative procedure. It does raise a legitimate question: given the apparent lack of domain competence of the Commission services in this highly technical domain, how wise it is for Recital (108) to indicate that “In order to ensure the effectiveness of this Regulation, the power to adopt acts in accordance with Article 290 TFEU should be delegated to the Commission in respect of further specifying technical elements of the definitions set out in this Regulation in order to adjust them to market and technological developments.”?

-77. To sum up, MiCA appears as a rushed affair which bludgeons its way through the most interesting legal aspects raised by blockchain and crypto-assets. The final version adds some specificity and improves on the inept Commission proposal but remains insufficiently specific. Despite its lofty claim to using an “incentive-based approach”, it responds to the legal challenges generated by the novel ways of interacting, which the technology makes possible, by banning those novel ways straightforward. It overlooks the deeper questions of legal theory and by delegating further power to the Commission it signals indifference toward the potential of the innovation. It also, in a sense, indicates pragmatism.

[203] Transit Protocol, “Business Modelling: Why Selling Shovels During a Gold Rush is the Surest Way to Make Money”, 2020

[204] A. Asmakov, “What are Proof of Reserves and Why Do They Matter?” 2022

[205] Chainalysis, “The 2023 Crypto Crime Report”, 2023

[206] Regulation (EU) No 596/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on market abuse (market abuse regulation) and repealing Directive 2003/6/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Directives 2003/124/EC, 2003/125/EC and 2004/72/EC

So MICA is not really interested in the growth of Crypto assets but places premium interest on the profits that would be made off it. They are the 'gold-diggers' who are not after innovations but their own pockets.

100% percent. Humans are terrible 🤷♂️

It’s obvious that Mica is only after the money and they don’t really have any business with if crypto grows or not. That’s being selfish though

Yes. Saying one thing while pursuing a radically different objective

MICA's claims appear to be false or misleading. Is it really interested in the innovations of crypto assets?

MICA is being self centered. They are only after themselves not minding in the growth and development of Crypto assets

Indeed. Should the established world be expected to just give up the privileges it enjoys ?

Not although

Some people have this mindset to explore from the Blockchain as much as possible which is not Good