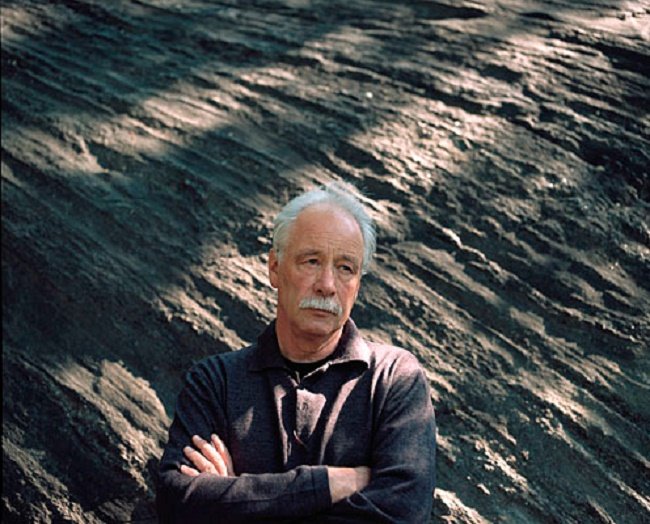

En la novelística internacional escrita y publicada en la última década del siglo XX sobresale, con una singularidad indiscutible, la obra narrativa del escritor de origen alemán, pero de formación inglesa, W. G. Sebald, como él mismo se identificaba. Estaría cumpliendo hoy –18 de mayo– 80 años, de no haber fallecido lamentablemente en un accidente automovilístico en 2001. Luego de su productiva trayectoria como profesor de literatura en la Universidad de Manchester y en la de Anglia del Este, se dedicó enteramente, a la edad de 40 años, a la escritura creativa. Fue autor de tres incomparables novelas: Vértigo (1990), Los anillos de Saturno y Austerlitz (2001) y del libro de relatos Los emigrados (1992), aparte de libros de ensayos.

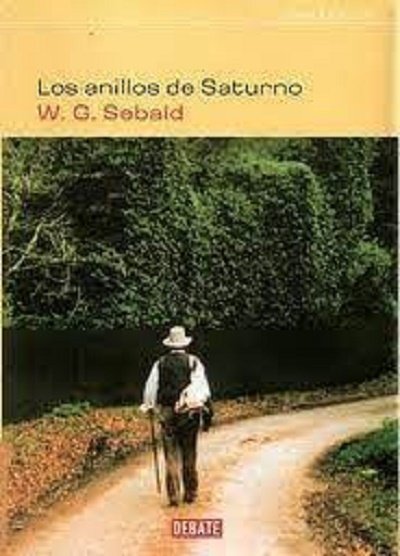

La creación narrativa de Sebald es una inteligente representación de lo que dio en llamarse "literatura posmoderna", pues en ella el relato toma un carácter proteico y transgenérico, y convive y se transforma en discurso ensayístico, autobiográfico, autorreferencial, etc. Así lo podemos percibir en su libro Los anillos de Saturno, al que dedicaré este post, con la reproducción de unos fragmentos.

Como se sintetiza en varias fuentes, se trata, en primer lugar, del relato de un viaje emprendido por el narrador (quizás alter ego de Sebald) por la costa inglesa del este (Suffolk), pero que se va a pluralizar en varios planos, con el uso de la digresión mediante los comentarios ensayísticos, la incorporación de fotos, las rememoraciones, la referencia a aspectos científicos, entre otros recursos.

De este modo, Sebald, a través de su narrador sin nombre, combina la reflexión sobre el tiempo, la decadencia o deterioro y la muerte, manteniendo una constante oscilación entre la realidad y la ficción, la naturaleza y la civilización, lo autobiográfico y las historias personales o de acontecimientos (el Holocausto como referente subyacente), la anexión de referencias a escritores (Chateaubriand, Conrad, Kafka, Borges), científicos escritores (Thomas Browne, por ejemplo), a pintores (v.g. Rembrandt).

Utiliza imágenes claves, como las que ya están en su título, para dar el tono de su relato, pero también, en parte, su estructura. Así, los anillos permiten pensar en la circularidad y circulación del discurso y sus historias, pero el valor de la experiencia propia y también el temple melancólico, asociado a Saturno (lo saturnino).

A continuación reproduciré algunos fragmentos.

Este es su comienzo, luego de tres epígrafes, donde resalta el primero de El Paraíso perdido de John Milton: "El bien y el mal que conocemos en el campo de este mundo crecen juntos casi inseparablemente".

En agosto de 1992, cuando la canícula se acercaba a su fin, emprendí un viaje a pie a través del condado de Suffolk, al este de Inglaterra, con la esperanza de poder huir del vacío que se estaba propagando en mí después de haber concluido un trabajo importante.

Con los ademanes convulsivos propios de un ser que por primera vez se ha levantado de la horizontalidad de la tierra, me apoyaba de pie, contra el cristal, pensando involuntariamente en la escena en la que el pobre Gregor Samsa, aferrándose al respaldo del sillón con patitas temblorosas, mira fuera de su habitación hacia un recuerdo impreciso, según el libro, de la liberación que para él había supuesto mirar por la ventana. Y exactamente como Gregor, con los ojos empañados, no reconocía la tranquila calle Charlott, donde vivía con los suyos desde hacía años, y la tenía por un páramo gris, también a mí la ciudad familiar, que desde los antepatios del hospital se extendía hacia el horizonte, me era completamente ajena.

Destaca la relación intertextual con el personaje de La metamorfosis de Franz Kafka.

Ya antes, cuando era niño, contemplaba al atardecer desde el fondo del umbroso valle a estos voladores, en aquel tiempo en un número incluso mayor, girando allí arriba, en la última luz, y me imaginaba que el mundo sólo se sostenía por las trayectorias que las golondrinas esgrimen en el espacio. Muchos años después leí el escrito publicado en Salto Oriental, Argentina, 1940, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius sobre la salvación de un anfiteatro entero por un par de pájaros. Entonces me percaté de que las golondrinas cazaban exclusivamente en la llanura que se extendía desde la elevación en la que estaba sentado hacia el vacío. Ni siquiera una sola de ellas subía más alto que las demás o se sumergía más profundamente hacia el agua. Y cuando, como una ráfaga, se acercaban a la orilla, algunas desaparecían siempre justo bajo mis pies, como si el suelo de la tierra se las hubiese tragado.

Aquí el autor juega con la referencia al cuento de Jorge Luis Borges.

Y Thomas Browne, que, como hijo de un comerciante de seda, debía de entender especialmente de esta cuestión, apunta en algún lugar de su escrito Pseudodoxia Epidemica, que me ha sido imposible encontrar, que en la Holanda de su tiempo era costumbre que en la casa de un difunto se tapasen con crespón de seda de luto todos los espejos y todos los cuadros en los que se podían contemplar paisajes, seres humanos o los frutos de los campos, para que el alma que está abandonando el cuerpo no se distraiga en su último viaje, ya sea por su propia mirada, ya por su tierra natal, pronto perdida para siempre.

Y con estas líneas cierra la novela sui generis de Sebald, volviendo a las imágenes que ha venido usando de la seda y el gusano de seda, para finalizar, de un modo expresivamente ambiguo y sugerente, con el múltiple significado de la pérdida y la muerte que atraviesa toda la obra. Su narrador en algún momento declara: "Nosotros, los supervivientes, lo vemos todo desde arriba, vemos todo al mismo tiempo y sin embargo no sabemos cómo fue".

Click here to read in english

A cult novelist: the German W. G. Sebald

In the international novels written and published in the last decade of the 20th century, the narrative work of the writer of German origin, but of English training, W. G. Sebald, as he identified himself. He would be turning 80 today – May 18 – if he had not unfortunately died in a car accident in 2001. After his productive career as a professor of literature at the University of Manchester and the University of East Anglia, he dedicated himself entirely to the age of 40, to creative writing. He was the author of three incomparable novels: Vertigo (1990), The Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz (2001) and the book of short stories The emigrants(1992), in addition to books of essays..

Sebald's narrative creation is an intelligent representation of what was called "postmodern literature", since in it the story takes on a protean and transgender character, and coexists and is transformed into essayistic, autobiographical, self-referential discourse. This is how we can perceive it in his book The Rings of Saturn, to which I will dedicate this post, with the commented reproduction of some fragments.

As summarized in several sources, it is, first of all, the story of a trip undertaken by the narrator (perhaps Sebald's alter ego) along the eastern English coast (Suffolk), but this will be pluralized on several levels with the use of digression through essayistic comments, the incorporation of photos, recollections, reference to scientific aspects, among other resources.

In this way, Sebald, through his nameless narrator, combines reflection on time, decay or deterioration and death, maintaining a constant oscillation between reality and fiction, nature and civilization, the autobiographical and the personal stories or events (the Holocaust with an underlying referent), the annexation of references to writers (Chateaubriand, Conrad, Kafka, Borges), scientific writers (Thomas Browne, for example), to painters (e.g. Rembrandt).

He uses key images, such as those already in his title, to set the tone of his story, but also, in part, the structure of it. Thus, the rings allow us to think about the circularity and circulation of discourse and its stories, but also the value of one's own experience and also the melancholic temper, associated with Saturn.

Below I will reproduce some fragments.

This is its beginning, after three epigraphs, where the first of <i<Paradise Lost by John Milton stands out: "The good and evil that we know in the field of this world grow together almost inseparably."

In August 1992, as the dog days were drawing to a close, I set out on foot through the county of Suffolk, in the east of England, hoping to escape the emptiness that was spreading within me after having concluded a important work.

With the convulsive gestures typical of a being that for the first time has risen from the horizontality of the earth, I stood against the glass, involuntarily thinking of the scene in which poor Gregor Samsa, clinging to the back of the armchair with With trembling legs, he looks out of his room towards a vague memory, according to the book, of the liberation that looking out the window had meant for him. And just as Gregor, with misty eyes, did not recognize the quiet Charlottenstrasse, where he had lived with his family for years, and considered it a gray wasteland, so did I see the familiar city, which stretched from the forecourts of the hospital towards the horizon, was completely foreign to me.

The intertextual relationship with the character of The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka stands out.

Even before, when I was a child, I watched at dusk from the bottom of the shady valley at these fliers, at that time in even greater numbers, spinning up there, in the last light, and I imagined that the world was only sustained by the trajectories that swallows wield in space. Many years later I read the writing published in Salto Oriental, Argentina, 1940, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius about the saving of an entire amphitheater by a pair of birds. Then I realized that the swallows hunted exclusively on the plain that extended from the elevation on which I was sitting into the void. Not even one of them rose higher than the others or sank deeper into the water. And when, like a gust, they approached the shore, some always disappeared right under my feet, as if the ground of the earth had swallowed them.

Here the author plays with the reference to the story by Jorge Luis Borges.

And Thomas Browne, who, as the son of a silk merchant, must have had a special understanding of this issue, points out somewhere in his writing Pseudodoxia Epidemica, which I have been unable to find, that in Holland In his time it was customary that in the house of a deceased person all the mirrors and all the pictures in which one could contemplate landscapes, human beings or the fruits of the fields were covered with mourning silk crepe, so that the soul that is Leaving the body, do not be distracted on your last journey, either by your own gaze or by your homeland, soon lost forever.

And with these lines he closes Sebald's sui generis novel, returning to the images he has been using of silk and the silkworm, to end, in an expressively ambiguous and suggestive way, with the multiple meaning of loss and death. that runs through the entire work. Its narrator at some point declares: "We, the survivors, see everything from above, we see everything at the same time and yet we do not know what it was like."

Referencias | References:

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._G._Sebald

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._G._Sebald

En este enlace puede descargar la versión en español de la novela en formato pdf, pero no contiene las fotos.

Esta publicación ha recibido el voto de Literatos, la comunidad de literatura en español en Hive y ha sido compartido en el blog de nuestra cuenta.

¿Quieres contribuir a engrandecer este proyecto? ¡Haz clic aquí y entérate cómo!

Me habían comentado sobre estas tres novelas, de hecho Vértigo está en mi casa materna, pero nunca me había sentido motivado a leer. Mi chica en alguna oportunidad leyó Los Anillos de Saturno y me hizo mención a que podría gustarme, pero bueno, si no es por tu publicación realmente habría olvidado todo. Siempre es grato pasar y aprender algo de sus publicaciones profesor, aunque lamenté leer cómo fue el trágico final del autor, seguramente habría portado mucho más, pero dejar una trilogía tal como usted la ha descrito aquí ya lo hace muy grande...

Gracias por tu lectura y tu personal comentario, amigo @jesuslnrs. Si tienen esos libros, es verdaderamente un privilegio. Trata de leer, al menos, Los anillos de Saturno. Un abrazo.