If you have ever been in a legal battle you know that the uncertainty of the outcome is one of the most stressful aspects. Regardless of the facts and circumstances, there is always a chance that the judge may not find in your favor. In many cases, a court loss can be as consequential as a car accident or total bankruptcy.

Which is better, a world where you have about a 50% chance of a 100% win or a world where you have a 100% chance of about a 50% win? If you only have one dispute in your life, you may not get enough rolls of the dice to produce the average outcome over time. Most people opt for insurance because they would rather have a guaranteed 1% loss (the insurance payment) than a chance of a 100% loss. From this perspective, a dispute resolution system that errors on the side of partial compromise may be better than one that probabilistically dispenses complete injustice or complete justice in proportion to the unavoidable ambiguity and errors of judgment.

How much would you pay for an insurance policy that covers your loss if you lose your case in court? How much would an insurance company charge to cover that risk? These are the questions that parties to a dispute should be asking themselves when evaluating their case and seeking a compromise. If both parties are rational and there is overlap in their evaluation of the risk of proceeding then a settlement is usually reached. However, in many cases, the parties’ risk assessments don’t overlap and the dispute proceeds to trial.

Regrettably, no one offers insurance for these situations and if they did the parties often wouldn’t have the money required to pay the premium. But what if there was another way that both parties could “buy” some insurance in their case? What if both parties could reduce the risk of the most extreme outcome? This post presents a process that can be adopted by disputes under arbitration that can achieve the effect of insuring both parties against worst-case outcomes.

The following process is best suited for civil cases where there is a question of law or the interpretation of a contract. If both parties have an honest difference of opinion and can see the ambiguity then they will likely find this process ideal. If you know your opponent is risk-averse and willing to compromise to avoid the worst case, then this process is for you. If you are risk-averse this process is for you. If you know your case is a loser, this process will likely get you something rather than nothing. Even if you are 100% certain of complete victory, this process lowers your risk.

The Process

- Two parties reach an impasse so they choose to arbitrate

- Traditional discovery process occurs to collect evidence

- Both parties present their best claims, arguments, and evidence

- Both parties present their best counter-arguments and counter-evidence

- Both parties present their best offer in compromise along with an explanation of the compromise at the same time.

- Either party may choose to accept the other party’s offer, or

- Both parties present an argument against the other party's compromise.

- The judge picks the fairest offer in compromise presented by the parties

The primary difference in this process is that the judge has far less discretion in determining damages and remedies. The judge is limited to selecting one of the two proposals as being the most fair resolution of the case.

A critical component of this process is that neither party gets to see the other party’s offer in compromise until after both parties have submitted their proposal. This blind offer process forces each party to provide a truly independent assessment of the quality of their arguments relative to the quality of their opponents to the judge in a way that doesn’t favor the last person to submit.

For example, assume a case that is truly ambiguous and both parties have equally strong arguments. If you believe the “true” odds of a fair judge’s ruling are 50/50 and you are about to submit a 50/50 proposal, but then learn your opponent has submitted a 100/0 proposal then you might adjust your proposal to 25/75 because even though you know it is less fair overall, it is still closer to fair than your opponents. A fair judge who sees the ambiguity and has an opinion that leans slightly in either direction would choose the 25/75 resolution unless the judge felt true justice would be best served by 88% or more in favor of the opponent.

By keeping proposals blind, one party would submit 50/50 and the other 100/0 and the judge would likely rule 50/50. The resulting outcome is more true to the independent measurements of multiple parties than it would be if one party got to see the compromise (or lack thereof) by the other before they presented their own. In effect, each party is encouraged to reveal their honest opinion about the natural ambiguity in the case rather than pretend their opponent’s arguments don’t exist.

Dividing a Cookie

There is a well-known process by which two parties can fairly divide a cookie without having to ask a third party to judge. The parties agree that one person will divide the cookie and the other party will choose which half they get. Assuming both parties desire the larger half, the person charged with dividing will be as fair as possible so that they are indifferent as to the choice of the other party. Any errors in their division are to the benefit of the other party, assuming the other party can accurately determine which side is bigger.

If a judge was hired to divide the cookie, he wouldn’t have as much incentive to divide it perfectly evenly because he doesn’t get either side. As a result, a judge dividing the cookie is more likely to leave one party with a smaller half than they are due.

Typical judicial rulings are like this judge dividing a cookie, they will be less precise and less fair. The proposed process is like asking each party to draw a line that divides the cookie and asking the judge to choose. Both parties will be attempting to divide it more accurately than the other party as measured by the judge. Note that dividing a cookie is harder than measuring the two halves and more prone to extreme errors.

Modified Cookie Division

Dividing a cookie solution works only when both parties agree that a 50/50 split is the proper solution and therefore the divider can be neutral to the chooser’s choice. But what if the parties don’t agree to a 50/50 split? Suppose they agree that it should be 80/20 but are fighting over what constitutes an 80/20 split. In this case, both parties propose an 80/20 split and the judge would rule on which proposal is closest to 80/20. This means that 2 out of 3 people agree that one of the proposals is the closest to 80/20. If the judge had simply divided it 80/20 then it is possible that both parties would feel they got less than they were entitled. In other words, only one person would have agreed that the division was 80/20 and the judge could have cut it as 20/80 or 90/10 with no checks and balances.

Disputed Cookie Division

What if the parties don’t agree about what share of the cookie they are entitled to? The process is exactly the same, except instead of the judge comparing the proposed divisions to the agreed ratio, the judge would be comparing the proposed divisions to his opinion of how things should be fairly divided. The proposed offer in compromise closest to the judge’s opinion wins.

In this case, the parties must divide the cookie in a manner that factors in their prediction of what a fair judge is likely to choose. The judge is presumed to be fair because both parties agreed to the judge’s selection.

Example Dispute

The cookie represents the total of all assets under the jurisdiction of the arbitration. In a land dispute, it might be the money paid, interest, attorneys fees, and the land itself. In a divorce, it would be the total estate of both parties and their future income streams.

For the sake of this example, let’s assume both parties think they should get the entire cookie. This means any compromise represents that person’s estimate of the risk that the judge chooses the other side. In a real dispute the compromise would be a blend between what they think is fair and the probability the judge thinks differently.

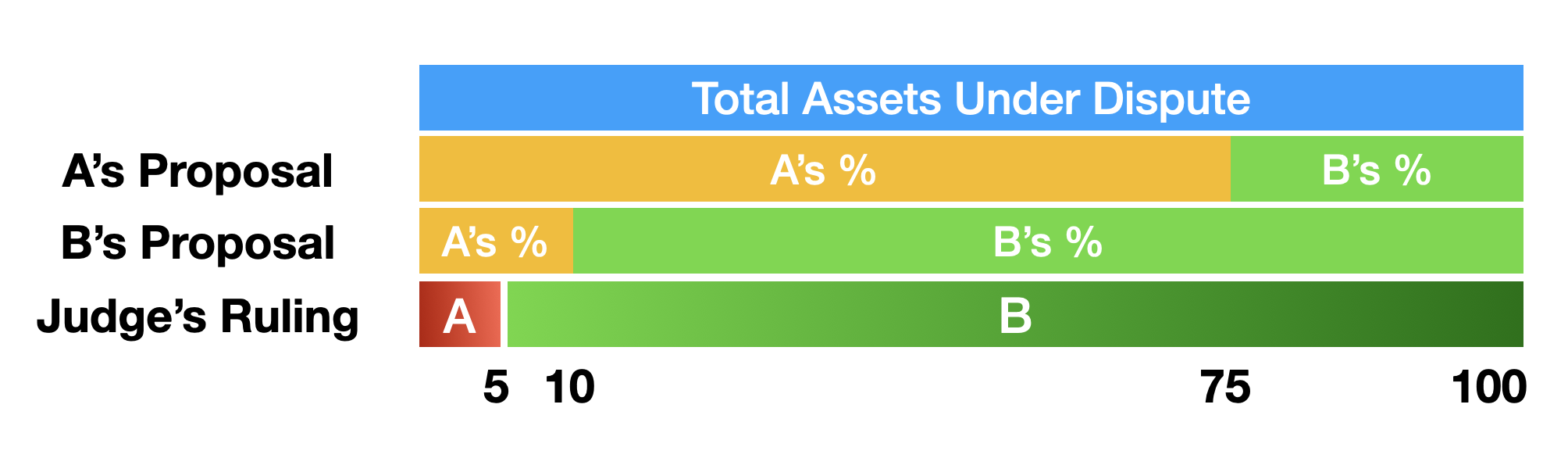

The diagram below shows that party A believes they have a 75% chance of getting the entire cookie. Party B thinks they have a 90% chance of getting the entire cookie. If the judge is torn and thinks 50/50 is the best answer, then A’s proposal is closest to 50/50 so the outcome of the dispute would be 75/25. If the judge thinks A should get 5% then he would go with B’s proposal because it is closest to A receiving 5%.

Incentive to Compromise

If party B (Bob) is overconfident and proposes A (Alice) get nothing and Bob gets 100%, then Bob increases the chances that the judge’s opinion will be closer to Alice’s proposal than Bob’s proposal. For example, if Bob had proposed 40/60 and the judge’s opinion ended up being 50/50 then Bob would have won and Alice would have lost. The impact of Bob’s willingness to compromise at 40/60 instead of 10/90 is that he would receive the 60% he proposed instead of the 25% Alice proposed.

The greater your compromise the higher probability your proposal will be closer to the judge’s than your opponent’s proposal. If you compromise too much then you are leaving money on the table.

In effect, both parties gain “insurance” from the worst-case outcome to the extent that the other party chooses to hedge their position. Both parties have an incentive to hedge their position because it increases the chances that they will win.

Signaling Confidence and Revealing Bullshit

Anyone who has been to court knows lawyers will argue the craziest theories just in case it works because they have almost nothing to lose. Everyone involved is subjected to hearing and defending against tortured arguments. Parties have little to lose and everything to gain if by some chance a judge is taken in by an unconventional legal theory. In truth, the parties may not even believe their own arguments but they make them anyway hoping to win.

When the parties are forced to submit offers in compromise, they end up revealing whether they truly believe what they are selling. If a judge sees one party argue that they are owed an extreme amount and then that party offers a huge compromise to the other party the judge can and should factor that into the weight he puts behind their arguments. It is a signal that the party is playing games rather than seeking an honest resolution to the dispute.

Let’s assume that Alice is extremely confident of winning so she proposes 90/10. Bob knows his chances of winning are slim, so he proposes 80/20 in favor of Alice. If the judge’s opinion without knowing Bob’s proposal was 84/16 then Bob would win for a net benefit of 10%. However, if the judge takes Bob’s proposal into consideration it may change his opinion. The judge would see that Bob wasn’t very confident in his own argument which may bias the judge toward A. Bob is in a catch-22, he wants to increase his chances of winning the compromise without signaling that he knows he is wrong and is hoping a judge can be duped into favoring his position anyway.

This signaling component forces both sides to be more honest in their arguments and increases the likelihood of Alice winning. Bob may only want to signal 50/50 because if he proposes 80/20 it would be more likely to push the judge toward Alice. The end result is that Alice would end up winning with a 90/10 split.

Incentives are Everything

The truth is a hard thing to get at when one or both parties are attempting to deceive and manipulate the judge to win at any cost. Few things, if any, are black and white. Every ruling is going to have some margin for error regardless of the process by which it was reached. The goal of justice should be to minimize the total amount of error and limit the extremes of miscarriage of justice.

Traditional processes maximize the incentive to lie, exaggerate, and present tortured, convoluted, unconventional, legal theories while appealing to the judge’s biases. They do not provide any incentive to admit any strength in your opponent's case. A party that dares to acknowledge the truth of ambiguity weakens its chances of justice. So everyone is forced to hold their nose and play the dirty game because transparency hurts.

My proposed process forces everyone involved toward the middle ground reduces the extremes and minimizes the errors of justice. It forces people to make an honest economic judgment of their own case and minimizes opportunities for judicial corruption and error. The end result is a fair compromise as agreed by one party and the judge, a 2/3 vote if you count 2 parties and 1 judge as the voters. Corruption could be further reduced by having a panel of judges reach a consensus. In most cases, one judge is likely less error-prone overall because the parties are forced to be more honest with themselves and the court and they know the situation better than any judge could.

Creative Solutions

One benefit of this approach is that the parties can propose more creative solutions than most judges would even consider. However, every benefit also comes with a dark side.

One danger of allowing both sides to propose court orders is that both proposals may have parts that are over-reaching or against public policy. Suppose Alice proposes she should be paid $10 million dollars from Bob and the judge finds this the most fair compromise. Suppose Bob’s compromise was that Alice should pay Bob $1 million to cover legal fees. The judge is about to go with Alice but then notices that Alice also wants Bob to wear a banana suit on a corner in a bad part of town for 3 days -- a term designed to ensure Bob gets a well-deserved beatdown. The judge would be forced to side with Bob; however, upon closer inspection, Bob also had a banana suit clause for Alice!

If both parties resort to such childish games, the judge would still be forced to pick the least offensive outcome because that is the only authority the parties granted the judge in the arbitration. That said, when the arbitration decision was taken to the courts the parties would have an opportunity to object to any terms that are against public policy or otherwise unconscionable. The same as with any contract dispute.

I experienced a real-world example of this in a divorce that used arbitration. The arbitrators decided both how to divide the property, alimony, and who should get custody. My ex-wife didn’t like the custody ruling so challenged the arbitration ruling in the courts. The courts found that the award was binding in terms of property and alimony but non-binding in terms of children's issues because children's issues can always be reviewed by the courts. My “fair and balanced” arbitration outcome which awarded alimony in exchange for my ex having to live in my town was gutted. My ex was allowed to move my kids 4 hours away and keep the alimony because the courts lacked the authority to overturn that part of the award.

If the arbitrator is forced to choose the least bad compromise with a banana-suit clause, then that clause can be challenged in traditional courts just like the children's issues were challenged in my divorce. Any unenforceable terms from the proposed arbitration ruling could be ignored or challenged. Suing to enforce the banana suit clause likely wouldn’t fly so it could be safely ignored.

Given the risk of losing your case in arbitration due to a ridiculous term that would ultimately be unenforceable, most parties represented by attorneys would never intentionally submit these abusive terms. If even one party is reasonable, the arbitrator will have to side with them.

Because both parties have an opportunity to respond to the other party’s proposed compromise before the judge rules; sneaky, non-obvious, and/or abusive terms will be brought to the judge’s attention and factored into the final outcome. Such bad behavior is not a good strategy.

Conclusion

With a few simple tweaks to the arbitration process, all parties can get insurance against extreme and arbitrary outcomes and a more just compromise. The incentives will be aligned for the parties to empathize with the arguments of the other side while refraining from arguing for outlandish legal theories. Economic theory demonstrates that human preferences cannot be revealed by surveys, but are revealed by their actions. You may claim you value healthy eating, but if you are caught eating doughnuts every day then your actions reveal the lie. Likewise, you may claim you believe your outlandish legal theory, but the action of making a proposed compromise under this process will tend to reveal the lie.

Therefore, in consideration of the points above, I believe it is in everyone’s interest, regardless of the facts and circumstances of their civil case, to adopt the process described in this post for arbitrated dispute resolution. It is the best way to reduce the risk of extreme and unpredictable outcomes for all parties involved. Some gamblers may choose to roll the dice with a conventional court process, but it is a high-stakes gamble that I believe is less likely to work in your favor.

As this is an untested process, please provide your thoughts on how it might work well and what might go wrong in the comments below.

Have you come across Sperner's lemma for dividing rent fairly among 2+ roommates? NYT has a tool for it https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/science/rent-division-calculator.html.

I'm curious whether it can be combined with the principles here for division of prized possessions beyond renting rooms.

One cuts, the other chooses is how Dad always managed these things with my brother and I.

Love this idea for arbitration.

It reminds me of this post I wrote about a similar rethinking of the referendum model.