Hi steemers, @federicopistono here.

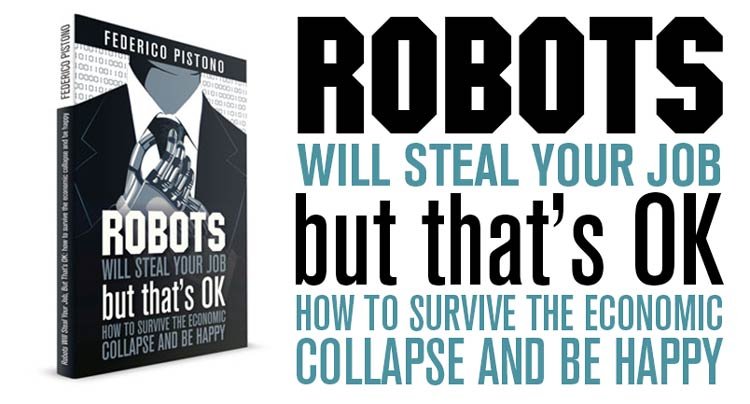

Today I'm publishing on Steemit in full the second chapter of my book Robots Will Steal Your Job, But That's OK, an international success published in seven languages, featured on Forbes, the BBC, The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, New Scientist, CNBC, and was subject of discussion at numerous universities as well as the European Commission, the Nobel Peace Center and the Italian Parliament.

Enjoy!

Chapter 2: The Luddite Fallacy

We are in England, at the end of the 18th century. A boy named Ned Ludd is a weaver from the village of Anstey, just outside Leicester. He does not know it yet, but he is about to make history.

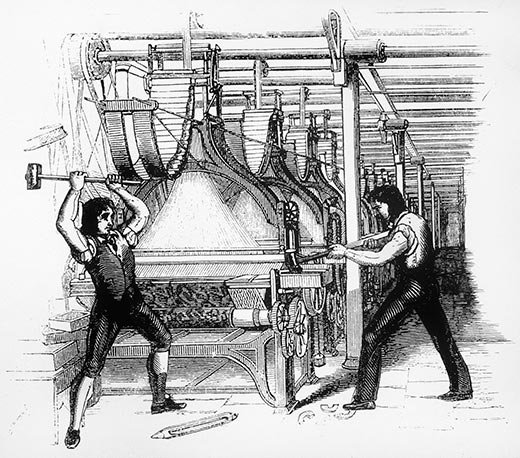

It is a hard and laborious day in 1779, Ludd is apprenticed to learn frame-work knitting. But he is averse to confinement or work, and refuses to exert himself. His master is displeased and complains to a magistrate, who orders a whipping. In response, Ludd grabs a hammer and demolishes the hated frame. This act will be told by generations to come, and Ludd became history. Or so the story goes.

As with every myth, there are many variations of the story. Some accounts say that Ludd was told by his father, a framework-knitter, to ‘square his needles’. Ludd took a hammer and ‘beat them into a heap’. Other stories can also be found, and nobody really knows which one is true, if any. [1]

Whether or not any of it really happened is irrelevant. What matters is that news of the incident, like every good folk story, was spread and distorted. Whenever frames were sabotaged, people would jokingly say, “Ned Ludd did it". His actions inspired the folkloric character of Captain Ludd, also known as King Ludd or General Ludd, who became the alleged leader and founder of a movement called, not surprisingly, ‘The Luddites’.

The Luddites can be traced back to Nottingham, England, around 1811. It was composed mostly of hosiery and lace workers, English textile artisans who protested against the changes produced by the Industrial Revolution – often by destroying mechanised looms. They smashed knitting machines that embodied new labour-saving technology as a protest against unemployment. Simply put, machines were stealing their jobs, and they did not like where that was going.

People began to speculate whether this was the beginning of an irreversible process, or if things would go back to normal. At the time automation was represented by no more than a steam-engine machine, something that could have hardly been seen as a realistic replacement for human labour in general. However, some suggested that the problem of machine automation could exacerbate in a few years, putting the very companies that produced goods at risk. Industrialist Henry Ford understood this quite profoundly. In fact, he paid his workers twice the going rate, so that they could afford to buy the cars that they themselves were producing.[2]

This makes sense. You need people to have enough money to buy the products you create, otherwise the cycle of production-consumption is interrupted. If automation replaces humans faster than they can find new occupations, you have a problem. As a result, people may get upset, and start to jeopardise machines, in order to ensure their workers not lose their job. To this day, we still call these people “Luddites".

Neoclassical economists have dismissed such proposition as nonsense. They claim that this argument is a fallacy. Economist Alex Tabarrok famously said in 2003 [3]

If the Luddite fallacy were true we would all be out of work because productivity has been increasing for two centuries.

And if you look around you, it would seem that the Luddite argument is indeed a fallacy. By studying the historical record, one should be pretty optimistic about the future of the economy. Automation and mechanisation have consistently been introduced, and that led to an increase in productivity. More work could be made, with less labour. More products were coming out of our factories. More wealth was generated. But the total requirement for labour did not decrease. As the economy grew, so did our standard of living. And our perception of what is necessary for a comfortable life changes accordingly. A hundred years ago, even the richest man in the world could not even dream of owning a small electronic device that could connect him with whomever he liked, anywhere in the world. Today, not owning a cell phone is inconceivable to most people. Even in the poorest countries, people have access to cell phones. A boy in a village in rural Africa with a cell phone (you would be surprised of how many of them do) has access to more information than the president of the United States did 20 years ago. Some have gone so far as to argue that the poorest of today are richer than the richest kings of the past. I would not agree with that, because many times it is cheaper to obtain these technological marvels than it is to find food. You get the idea.

Over the past two centuries we have continued to rely on machines to increase our productivity, but we have not been displaced by them. On the contrary, we created new jobs, new sectors, and new opportunities. Machines allowed us to become more creative, more productive. As we moved from the agricultural to the manufacturing sector, and then to the services, we began to expand our domination of the planet.

So, if the idea that automation creates unemployment is a fallacy, then there is nothing to worry about. The staggering rate of unemployment that we are experiencing today in 2012 (8.2% in the US, 24.1% in Spain, 21.7% in Greece, 14.5% in Ireland [4] ) is just one of the many cycles of the economy. Or it may be due to bad policies. Or bad politicians. Or the financial bubble of subprime mortgages that burst a couple of years ago. Maybe it is a combination of all of them. If that is the case, then we just need to elect better politicians, demand better reforms, and reduce the influence of the financial sector on the economy. In other words, it could be just a matter of time before things go back to normal. Get back on your feet, work hard, and everything will be fixed. I would like to believe that. I really would. But the reality may be very different.

While these resolutions are certainly good ideas, and they are necessary for creating a better society in which to live, they might not be sufficient. In fact, it might be that no matter how hard we try, how good the new wave of politicians will be, how resourceful our businesses are, or how ingenious we can be, we will never escape from this crisis. We do not know if that is the case. But it is a possibility, one that we should carefully consider and explore.

Kurt Vonnegut has claimed to have said so much at a private girls school, when he gave a commencement address: [5]

Things are going to get unimaginably worse, and they are never, ever, going to get better again.

I know it is not exactly what you wanted to hear. The rising unemployment levels of the past years could be just the tip of a huge iceberg, and we all could be riding a 21st century economic Titanic. I would like to believe that this is merely unjustified pessimism. But beliefs are heavily influenced by emotions, and the truth does not care what we believe. It just is.

So, how should we approach this conundrum? Will you be the eternal optimist, having faith in the power of the market to adjust itself every time there is a new challenge? Or will you be the incorrigible pessimist, who believes we are doomed, and there is no hope left? Which side will you take?

You see, I do not think it is a matter of picking sides. Or beliefs. Or gut feeling. I would like to take an objective position, as much as possible. I believe in good data, and good logic to interpret that data. I think we should cast aside our ideologies, our personal hunches, and we should use our reason to try and predict the future from an informed perspective. If we want to do that, we are going to have to explore a few things first. These are not difficult ideas. In fact, once explained properly, they are quite simple. But they are also remarkably useful and amazing tools that help us understand the world around us better. Believe it or not, these tools are so basic that they could be easily taught in elementary schools, yet I met many college graduates who failed to apply them at the most fundamental level. Obviously, it is not because these people are not smart enough to understand them, but because they have never been taught to think about the future using these tools.

I will try to explain these ideas to the best of my ability. If I succeed, you will be able to grasp these concepts quite easily, and with them you will see the world from a whole different perspective. You will have all the necessary tools to approach this challenging task, and make up your own mind about which side of the debate you should take. From there, we will take off, think about the future, and see how to live better accordingly.

Let’s get started.

Chapter 2: Notes

- The Skilled Labourer 1760-1832, Hammond, J.L.; Hammond, Barbara, 1919. London: Longmans, Green and co.; p. 259. http://www.archive.org/details/skilledlabourer00hammiala

- Difference Engine: Luddite legacy, 2011. The Economist. http://www.economist.com/blogs/babbage/2011/11/artificial-intelligence

- Productivity and unemployment, 2003. Marginal Revolution. http://www.marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2003/12/productivity_an.html

- Harmonised unemployment rate by gender. Eurostat. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&language=en&pcode=teilm020&tableSelection=1&plugin=1

- American Notes: Vonnegut’s Gospel, 1970. Time Magazine. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,878826,00.html

Publication on Steemit

I decided the share my book, the result of years of work and research, with the Steemit community for free, to spark a debate and to raise awareness on this pressing social issue.

If you'd like to support my work, consider upvoting this post, or getting a copy of the book.

Where to find me:

Milton Friedman went to China where he was escorted around by government bureaucrats. They showed Friedman a canal-building project and he couldn't help but notice the lack of heavy machinery.

Friedman: "Why are all the laborers using shovels? Where are all the machines?!"

Bureaucrat: "You don't understand, this is a job-creation project!"

Friedman: "Oh, I thought you wanted to build a canal. If it's jobs you want, why don't you take away their shovels and give them spoons?"

The point is, it's not jobs that matter. What matters is wealth. The canal will make for more efficient commerce and create more wealth. In this example, the Chinese are shooting themselves in the foot by trying to create more jobs. Digging a hole just to fill it back up does no one any good.

Keep doing what you do! Hopefully we can purge these misconceptions once and for all.

Hi! I am a content-detection robot. This post is to help manual curators; I have NOT flagged you.

Here is similar content:

http://robotswillstealyourjob.com/read/part1/ch2-luddite-fallacy

Yes, it's my book indeed!

Thanks cheeta for indexing well my website, good robot! And thanks for proving my point, you already stole someone's job :D

Haha, your book has inspired many bot creators on Steemit, I think. :)

!cheetah whitelist

Okay, I have whitelisted @federicopistono. I won't bug them.

Amazing!!!

You couldn't plan this any better. I think that Cheetah has chosen to embrace automation.

Excellent post too!!!

I had a chat with some of my friends, we all work in the petroleum industry about fusion power and how it would change our lives forever. At least one shat himself. People are so scared of change, even theoretical.

Robots are not bad, but you need to make the prices decrease then, which is not the case with all the inflation that is going on. It's inflation that erodes the benefits of automation.

We can only hope that robots take over our jobs sooner rather than later. It is inevitable and everything will most likely adjust appropriately. I ran into the term "Luddite" a few years ago when I was giving a 65 year old computer lessons, he would frequently get upset with the computer and tell me he is "a Luddite when it comes to technology". I had to google it. Thanks for the article, another good one!

As you have mentioned Vonnegut above - there's another quote from Sirens of Titan, it fits theme: "Every passing hour brings the Solar System forty three thousand miles closer to Globular Cluster M13 in Hercules — and still there are some misfits who insist that there is no such thing as progress"

Wow, This is a great read and display of writing! Got to follow your work now:)

I typically don't like reading those types of books... But after reading chpt.2 for free i was pretty upset to not have chpt.3 to read.

Now i'm probably going to have to go buy your book.

It never fails to amaze me the panic that can be induced when you mention automation. I can't begin to count how many so-called liberals start wringing their hands when you talk about freeing up workers from menial tasks by automating them.

Will it displace workers? Sure, but the net gain in productivity benefits everyone. More products for lower prices. Workers will retool and reorient; they always have. One thing that is a virtual guarantee in this world is the tenacity of human ingenuity.

Interesting book, does it at all go over division of labor and the affects of automation?