Hey guys!

At first…

To start with, I have one remark on my own behalf: Because I treat in my articles mainly (chemical) things from everyday life and I plan to write quite a few in the future, I decided to run this series under the headline “Science for Everybody” from now on. It starts with #4 because I cannot edit the first articles anymore.

I’d also like to point out, that I intentional don’t want to go into the deep from a scientist’s point of view, use many formulas or something, but I want to try to make the background easy understandable for everyone. If someone wants to know more details, it is then always possible to access them with other sources.

Today’s topic

The aim of this article is to make clear some basics. Sorry if it might be boring today. The basics are important for some future topics and so I may refer to this post and use the saved words for further explanations of other things.

Today, we look at the structure of atoms first and then we will see how metals distinguish from nonmetals and how compounds are formed.

The atom

I’d like to keep the general imagination of an atom as simple as possible. If we need it more detailed someday, we can deepen our understanding. In the first post of this series, I already gave you a basic image of atoms. It is based on the atomic model by Niels Bohr and today, we want to expand it a little more:

The structure

So, atoms are made of a solid core. Around this, there are onion-like shells. The core itself consists of the so-called nucleons. These are two types of particles: the protons and the neutrons. Both have about the same weight. But, they distinguish from each other because protons are electrical positive charged and neutrons have no charge, so they are electrical neutral. In the shells, there are the electrons. Contrary to their colleagues, they have nearly no weight at all and they have an electrical negative charge. So, they are kind of a counterpart of the protons. An atom itself is always electrical neutral altogether. This means, there must be as many electrons as protons to make the charges equalize each other.

The arrangement of electrons

The number of protons determines to which element our atom belongs. For example, every hydrogen atom has 1 proton, every oxygen atom 8 protons and every gold atom has 79 protons. Contrary, the number of neutrons may vary. So, the so-called isotopes form which we may discuss in another article.

The electrons are spread on the shells. For this, there are several rules. At the moment, the most important of these has to do with the number of electrons per shell. There may not be a random number on a shell, because the negative charges push off (like magnets with the same orientation).

The innermost shell has room for two electrons, the second for eight, the third for 18 and every other for 32 electrons. Because our electrons are so lazy, they fill the shells beginning from the innermost. But, there is one characteristic: on the outmost shell, there are maximum 8 electrons. If these are reached, the next shell will be begun and the other filled up later.

The reason for this behavior is, that 8 electrons on the outmost shell (by the way, these are called valence electrons) are especially stable. This can be seen by the fact, that every element with 8 valence electrons shows nearly no reactivity – these are the so-called noble gases which form nearly no compounds with other elements. Therefore, the state with 8 valence electrons is also called noble gas configuration. Because this configuration is so stable, every other element tries to reach it too.

Metals, semimetals and nonmetals

I presume that everyone has an imagination of a metal: most of them are light to dark grey, glossy substances. From a chemist’s point of view, another property is much more important: metals like to give away their (valence) electrons. If this happens, there are too much positive charges in the atom – an ion is formed (because it is a positively charged ion, it is called cation). Contrary, nonmetals like to take up electrons. So, a negatively charged anion is formed. The semimetals are somewhat undecided in this question and they behave (dependent from the partner) sometimes more like a metal and sometimes more like a nonmetal.

Compounds

Most of the atoms have no other choice than to work together to reach their 8 electrons – they form compounds. Here, we can distinguish three sorts:

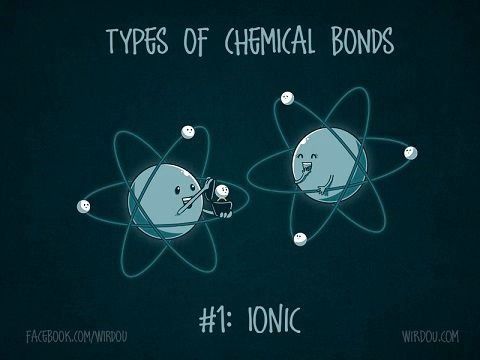

###The common thing between salt, stone and ceramics

The first possibility to get together is between a metal and a nonmetal. They make terms rather quickly, because the metal wants to give away its electrons and the nonmetal likes to accept them. Because so, there are formed two ions, it is called the ionic bond. The formed positively and negatively charged ions attract each other (like magnets with different orientation) and get surrounded by each other. The resulting compounds are called salts but many ceramics and minerals are also built up from ions. Generally, they melt at very high temperatures, isolate electric current in the solid state and they are very hard but brittle (i.e. they crack). It is not important; how many ions are part of the bonding as long as there equal positively and negatively charged ions.

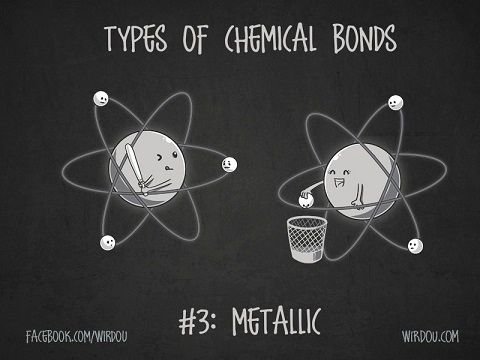

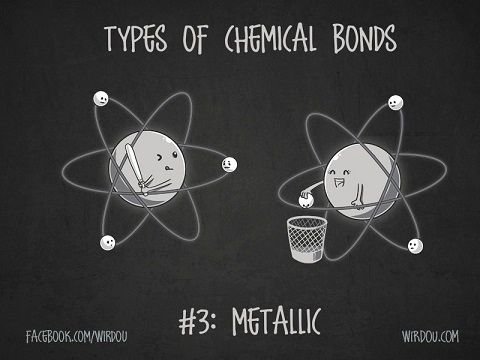

Metals among themselves

If a metal does not find a nonmetallic partner, it must arrange with its metal-colleagues. So, a metal in its pure state is formed (e.g. iron) or an alloy consisting of different metals. Because all of them want to give away their electrons, kind of collecting basin is opened. One imagination of the metallic bond bases on the picture, that all electrons are put together in a pot and then they are spread on all atoms (it is the so-called electron gas). This can move freely and leads to typical properties of metals (like electrical conductivity in solid and molten state and plasticity/forgeability). Here it is either not important, how many atoms are put together.

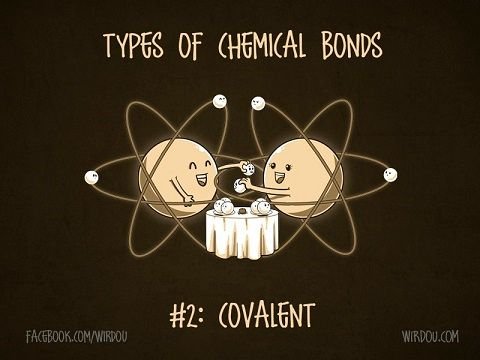

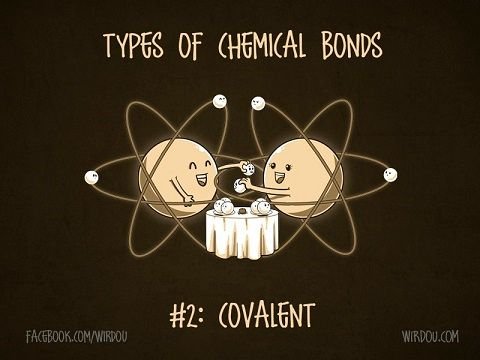

Two nonmetals and the difficult compromise

When two nonmetals meet, they both are in trouble: both want to have more electrons but none wants to give away some. The only way to make them reasonably happy is that they share the electrons with their neighbor. It is called a covalent bond and one bond is always formed of two electrons which count for both atoms then. Therefore, some atoms must form more than one bond. Thus, atoms cannot arrange in any number and their arrangement plays a role (some need only one bond, other three and so on). The resulting formations are called molecules. They have a well-defined structure in which they are strong bonded but two molecules stick to each other only relatively weak. Therefore, typical molecule-based compounds have relatively low melting and boiling points and are liquid or even gaseous at room temperature (e.g. oxygen, water or fuel).

Terminating for now

I hope you stayed with me with this rather boring stuff and you will be with me next time anyway. Unfortunately, sometimes we need to open the scope a little bit. Next time we will surely talk about some things of our everyday life. For this, I now may refer to these explanations and you can look up, if you need to.

Sources of the cartoons: https://wirdou.com/

Hallo Leute!

Zunächst einmal…

Vorab eine Bemerkung in eigener Sache: Da ich mich in meinen Artikeln hauptsächlich (chemischen) Dingen aus dem Alltag widme und es sicherlich noch einige mehr werden, habe ich beschlossen, diese Reihe ab heute unter der Überschrift „Wissenschaft im Alltag“ laufen zu lassen. Es startet mit #4, da ich die ersten drei Artikel leider nicht mehr editieren kann.

Ich möchte außerdem nochmal betonen, dass ich ganz bewusst aus wissenschaftlicher Sicht nicht in die Tiefe gehe, viele Formeln verwende oder ähnliches, sondern versuche, die Hintergründe soweit verständlich zu machen, dass jeder sie verstehen kann. Wenn jemand mehr Details möchte, ist es dann immer noch möglich, über andere Quellen tiefer einzusteigen.

Heutiges Thema

Der heutige Artikel soll dazu dienen, einige – möglicherweise langweilige (sorry dafür!) – Grundlagen zu erläutern. Diese sind sicherlich für einige andere Themen nötig, die ich in Zukunft behandeln werde und so kann ich bei Bedarf immer wieder auf diesen Artikel verweisen und den gesparten Platz nutzen, um andere Dinge ausführlicher zu erklären.

Heute geht es darum, wie Atome grundsätzlich aufgebaut sind, was Metalle und Nichtmetalle unterscheidet und wie Verbindungen entstehen.

Das Atom

Ich möchte die grundsätzliche Vorstellung von Atomen so einfach, wie möglich halten. Falls wir doch nochmal tiefer einsteigen müssen, werden wir das zu gegebener Zeit tun. Ein grundlegendes Bild von Atomen habe ich euch in meinem ersten Post dieser Reihe schon erzählt. Es basiert auf dem Atommodel von Niels Bohr und soll heute noch etwas erweitert werden:

Der Aufbau

Atome bestehen also aus einem festen Kern, um den sich – wie bei einer Zwiebel – Schalen befinden. Der Kern selbst ist aus sogenannten Nukleonen aufgebaut. Dabei handelt es sich um zwei Sorten Teilchen: Protonen und Neutronen. Beide sind etwa gleich schwer, was sie aber unterscheidet ist, dass die Protonen elektrisch positiv geladen sind und die Neutronen elektrisch neutral, also ungeladen. In den Schalen befinden sich die Elektronen. Diese wiegen im Gegensatz zu ihren Kollegen fast nichts und sind elektrisch negativ geladen. In dieser Hinsicht sind sie also so etwas wie die Gegenspieler der Protonen. Ein Atom ist dabei selbst immer als Ganzes elektrisch neutral – das bedeutet, es muss immer genau so viele Elektronen wie Protonen geben, damit die Ladungen sich gegenseitig aufheben.

Die Anordnung der Elektronen

Die Anzahl der Protonen legt fest, um welches Element es sich bei dem Atom handelt – so hat z.B. jedes Wasserstoffatom 1 Proton, jedes Sauerstoffatom 8 Protonen und jedes Goldatom 79. Die Zahl der Neutronen dagegen kann variieren. Dadurch entstehen die sogenannten Isotope, worüber wir evtl. ein anderes Mal reden.

Die Elektronen verteilen sich nun auf die Schalen. Hierbei gibt es bestimmte Regeln, von denen die für uns im Moment wichtigste mit der Anzahl der Elektronen pro Schale zu tun hat. Es können nämlich nicht beliebig viele von ihnen in einer Schale sitzen, da die negativen Ladungen sich gegenseitig abstoßen (wie gleichpolige Magneten).

In der innersten Schale ist nur Platz für zwei Elektronen, in der Zweiten für acht, in der Dritten für 18 und in jeder weiteren Platz für 32 Elektronen. Da unsere Elektronen so faul sind, füllen sie die Schalen von innen auf. Eine Besonderheit gibt es dabei: Auf der äußersten Schale sind immer nur 8 Elektronen, dann wird erstmal die nächste angebrochen und die andere später aufgefüllt.

Der Grund hierfür ist, dass 8 Elektronen auf der äußersten Schale (diese nennt man übrigens Valenzelektronen) besonders stabil sind. Man kann dies daran sehen, dass alle Elemente, die 8 Valenzelektronen besitzen, besonders unreaktiv sind – es handelt sich dabei um die so genannte Edelgase, die fast keine Verbindungen mit anderen Elementen eingehen. Die Anordnung mit 8 Valenzelektronen heißt daher auch Edelgaskonfiguration. Und weil diese Anordnung so stabil ist, versuchen alle Atome, sie nachzumachen.

Metalle, Halbmetalle und Nichtmetalle

Unter einem Metall kann sich vermutlich jeder von uns etwas vorstellen: Die meisten von ihnen sind hell- bis dunkelgraue, glänzende Stoffe. Aus Sicht des Chemikers ist eine andere Eigenschaft wichtiger: Metalle geben ihre (Valenz)Elektronen relativ leicht ab. Wenn das passiert, bleiben natürlich positive Ladungen übrig – es bildet sich ein elektrisch geladenes Teilchen, ein Ion (da es ein positives Ion ist, nennt man es Kation). Nichtmetalle dagegen nehmen viel lieber Elektronen auf, dabei bildet sich ein negativ geladenes Anion. Halbmetalle können sich diesbezüglich nicht so recht entscheiden und sind je nach Partner manchmal mehr wie ein Metall und manchmal mehr wie ein Nichtmetall.

Verbindungen

Um ihre 8 Elektronen zu erhalten, bleibt den Atomen meistens nichts anderes übrig, als sich zusammenzutun – sie bilden Verbindungen. Hierbei können wir drei Arten unterscheiden:

Was Salz, Stein und Keramik gemeinsam haben:

Die erste Möglichkeit, sich zusammenzutun besteht zwischen einem Metall und einem Nichtmetall. Beide sind sich dabei schnell einig, da das Metall seine Elektronen gerne abgibt und das Nichtmetall sie haben will. Da sich dabei jeweils ein Ion bildet, spricht man auch von der ionischen Bindung. Die entstehenden positiv und negativ geladenen Ionen ziehen sich gegenseitig an (wie ungleich gepolte Magneten) und umgeben sich gegenseitig miteinander. Die resultierenden Verbindungen nennt man Salze, aber auch viele Keramiken und Minerale sind so aufgebaut. Sie sind im Allgemeinen dadurch gekennzeichnet, dass sie erst bei sehr hohen Temperaturen schmelzen, im festen Zustand keinen Strom leiten und sehr hart, aber spröde (d.h. sie brechen) sind. Es ist in erster Linie egal, wie viele Ionen sich beteiligen, solange insgesamt gleich viele positive und negative Ladungen da sind.

Metalle untereinander

Findet ein Metall keinen nichtmetallischen Partner, so muss es sich wohl oder übel mit anderen Metall-Kollegen vergnügen. Hierbei entsteht das Metall in reiner Form (z.B. Eisen) oder eine Legierung aus verschiedenen Metallen. Da alle ihre Elektronen abgeben wollen, wird eine Art Sammelbecken eröffnet. Eine Vorstellung der metallischen Bindung beruht darauf, dass einfach alle Elektronen in einen Topf geworfen werden und sie sich anschließend um alle Atome verteilen (man spricht vom sogenannten Elektronengas). Dieses ist frei beweglich, was zu den typischen Eigenschaften (wie elektrische Leitfähigkeit im festen und flüssigen Zustand und Verform- bzw. Schmiedbarkeit) führt. Dabei ist es ebenfalls egal, wie viele Atome sich an dem gemeinsamen Konstrukt beteiligen.

Zwei Nichtmetalle und der schwierige Kompromiss

Bei einem Zusammentreffen zweier Nichtmetalle haben beide ein Problem: Beide wollen gerne mehr Elektronen haben, aber keiner möchte etwas abgeben. Der einzige Weg, um beide halbwegs zufriedenzustellen, besteht darin, dass sie ihre Elektronen mit ihrem Nachbarn teilen. Man nennt dies eine kovalente Bindung, wobei eine Bindung immer aus zwei Elektronen besteht, die dann zu beiden Atomen zählen. Daher müssen die Atome evtl. mehrere Bindungen ausbilden. Dies führt dazu, dass sich nicht beliebig viele Atome miteinander verbinden können und auch ihre Anordnung eine Rolle spielt (manche brauchen nur eine Bindung, andere 3 usw.). Die entstehenden Gebilde werden dann Moleküle genannt. Sie haben eine definierte Struktur und sind innerhalb sehr fest gebunden, zwei Moleküle allerdings hängen nur lose zusammen. Typische Molekülverbindungen haben daher meist einen eher niedrigen Schmelz- und Siedepunkt und sind bei Raumtemperatur flüssig oder sogar gasförmig (z.B. Sauerstoff, Wasser, Benzin).

Zum Abschluss

Ich hoffe, ihr konntet mir heute mit dem etwas trockenen Stoff folgen und dass ihr beim nächsten Mal trotzdem wieder dabei seid. Leider muss man manchmal etwas weiter ausholen und nächstes Mal wird es bestimmt wieder etwas anschaulicher um Dinge in unserem Alltag gehen. Dafür kann ich jetzt jederzeit auf diese Beschreibungen zurückgreifen und ihr könnt bei Bedarf dann hier nachlesen.

Quelle der Cartoons: https://wirdou.com/

Steemit definitely needs more people like you for sharing great science/education posts!

As a bonus, and in addition to resteeming for exposure, we are awarding you a small 10 Steem Power deposit as a thank you for creating quality STEM related postings on Steemit. We hope you will continue to educate us all!

Thank you guys! I definitely will continue and I hope that people like my content and can learn something out of them. :-)

Wow da hast du dir mächtig Arbeit gemacht mit! Das gibt 100% jetzt ists mir aber schon zu spät zum lesen :-) morgen dann hoffentlich. EDIT: warum votest du dich nicht selbst?

Danke dir!

Tatsächlich, weil ich eben keine Zeit mehr hatte. Zudem gab es ja bzw gibt es Diskussionen, ob man das Selbsvoting nicht lassen oder unterbinden sollte wegen der HF 19. Es macht zwar bei mir noch nur wenig Geld aus, aber ich verzichte jetzt einfach mal aus Prinzip darauf ;-)

Deine Artikel kannst du auf jeden Fall selbst voten (es ging eher um die Kommentare).

Genau, wieder etwas ungenau ausgedrückt von mir. Frage war warum du deinen Artikel nicht selbst votest ;-)

Na wie ihr meint, dann werde ich das wohl noch nachholen ;-)

"Votet" man nicht automatisch für seinen Artikel ? Bei mir ist das auf jeden Fall so ?

Kommt drauf an, ob du das Häkchen setzt oder nicht ;-)

Very nice post. I like the way you explained simple and sound, so that even the starters can understand. I had read full so that i can recollect it again. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you! I'm glad that you like my way to explain things.

Excellent post, followed and resteemed. Looking forward to your future articles!

Thank you! I hope, I don't disappoint you ;-)

That was a very clear chemistry lesson! Please write more! We need more good (and real) science posts on steemit!

Thank you!

I have already some ideas for the next articles, so stay tuned! ;-)

I will keep my eye open, even if chemistry is not really my field ^^

Nice job with this chemistry lesson! You need to make yourself a fancy thumbnail image for your series here. I like the name "Science for Everybody."

Thank you!

Indeed, I thought about such a thumbnail. But for now, I have not really an idea what it should look like. I'll see, what I can do about it because it would be a nice help to identify the series. :-)

Sehr schön erklärt, da kommen sogar Chemie-Nieten mit! :-)

Freut mich! Ich versuche auch, jeden mit den Grundlagen zu versorgen. Vertiefen kann man es dann immer noch, wenn genügend Interesse geweckt ist. ;-)

Ehrlich gesagt bin ich froh, dass ich es nichtmehr wissen muss. Aber wenn ich das damals gelesen hätte, hätte ich dir wahrscheinlich Steemits rübergeschoben, für diese aufschlussreichen Artikel :-D

Ich hab mal irgend nen Elementereim gemacht, dass ich mir die Reihenfolge merken kann, weiß aber nicht wieso genau diese Reihenfolge...

Ar-Na-Ne Be-Li-He! (Muss man aussprechen wie wenn man das bei einer Demo als Protestsong singt!)

Macht das irgendeinen Sinn?

Naja, es ist bei mir auch so, dass Sachen, die ich wissen muss/soll tendenziell schlechter hängen bleiben, als die, die ich wissen will. Aber man lernt ja auch nie aus, und wie gesagt, vielleicht ist ja auch mal was dabei, was dich schon immer interessiert hat. Oder du stellst Fragen für mich zur Anregung für neue Themen ;-)

Aus deinem Reim werde ich insofern schlau, dass Be-Li-He die umgekehrte Reihenfolge des Periodensystems ist. Für die anderen drei müsste es aber dann Mg-Na-Ne bzw. Ca-K-Ar sein ;-)

Vielleicht waren es auch nur zufällig gewählte Elemente, die unser Physiologielehrer als sinnvoll empfunden hat um dieses Schalen-Gedöns zu erklären. Ich hoffe dieser Begriff beleidigt dich nicht, aber ich finde auf die Schnelle jetzt keinen besseren Begriff. :-)

Wenn mir was einfällt (wahrscheinlich geht es dann um Reinigungsmittel oder sowas) bist du der Erste, den ich fragen werde!

Reinigungsmittel bzw. Seife... Ist notiert! :-)

Top!

It's nice to see so many good science content creators on this platform, upvoted and followed!

I'm also creating such content, if you want to take a look and leave some feedback it would be great :-) I hope to see more of your posts in the future!

Will keep an eye out :)

Thank you :-)

Thank you!

I'll take a look at your content later. For now, I have to recover my voting power a little bit ;-)

Whenever you want! Since I really like the kind of content you are creating , it would be nice to have your feedback and maybe, in the future, consider a collaboration on some project :-) In the meanwhile I'll wait for your future posts!

Sounds like a good idea!

As I said, I will look at your stuff when I'm able again to upvote it, so it would be better (for you) ;-) Besides, I have to work now a little bit. It is such a strange thing - I think, they call it real life or so... ;-)

I fully understand, I guess i have to do the same now. Have a good day :-)

Das war ein ziemlich guter Blogpost, Liebe Grüße Harald Lesch

Was? Harald Lesch ist auf Steemit? Ich werd verrückt... ;-)

Danke dir!

Well, I learned something new. I didn't know about the metals putting electrons in a pot (metaphorically speaking) which allows for free flowing of the electrons. It's good to know about the physical mechanisms behind the properties we see on the macro level (electrical conductivity in this case). I'm looking forward to the next articles in the series.

Thank you. In fact, this is one simple model to understand the bonding in metals. Actually, it is a bit too simple, because it doesn't explain effects like the metallic shine. But maybe, we come back to this in a future article. :-)

Science is life!

Thanks for sharing.

upvote would be appreciated. i´m also a science blogger and it can be hard .. you are commenting but not upvoting, why?

They exhaust all their voting power by upvoting their own comments ... (really a bad side effect of HF 19 to make self-voting so lucrative, as in the long run it will be very bad for the Steem price ...)

Wow! Thank you so much for educating us. Keep up the good work!

Such a great article, so many comments, but not a single upvote?!?

Let's change that!

I won over you. I was the upvoter #1 :D

I had to write the comment first. :)

Ok guys. Maybe we should offer a price for the first comment and the first vote next time? :-P

I fear a bot would win it then ...

Thank you! Seems like someone has to start with voting ;-)

I love Steem. It is growing so much. It looks there is a topic for everyone.

Honestly >>> Very good

then please upvote

Sehr guter Beitrag. Danke dafür!!!

I know @thepe , he is rather friendly, and I am really sure he wouldn't be angry at you in case you upvote his article - so just dare it! :)

(In that case I may actually consider to upvote your comment as well. :)

I'm not sure, if you got me right in the past... ;-) Maybe, I just played the friendly guy? :-P

Bitte, gerne! ;-)