James Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake is not a dream, but it is punctuated by dreamlike interludes. The first of these, and one of the best known, is the Museyroom episode in Chapter 1. This short passage—it occupies less than two pages in The Restored Finnegans Wake, or two-and-a-half if we include the prologue—distils the very essence of Finnegans Wake: it is narrated by one of the principal characters, Kate, which gives it a unique turn of phrase and tone of voice : it can be interpreted simultaneously on several different levels or narrative planes : it has a flowing rhythm that one might describe as musical : it has a Viconian structure : it resonates throughout the rest of the novel.

In an earlier article in this series I pointed out how most of the salient moments from later in the book are foreshadowed by some episode in Chapter 1. If Finnegans Wake were an opera, the opening chapter would be the overture that is played by the orchestra before the curtain rises and that contains all the principal themes and melodies of the opera. And this applies especially to the Museyroom episode, which foreshadows another famous episode in the novel: Butt and Taff, Book II, Chapter 3§4-6.

Two Anecdotes

When Joyce was drafting his earlier novel Ulysses, he planned to include in it two anecdotes he had heard in his youth from his father:

The Story of How Buckley Shot the Russian General

The Story of How Kersse the Tailor Made a Suit of Clothes for the Norwegian Captain

It is the first of these anecdotes that concerns us here. Joyce was very fond of this story and recounted it to several of his acquaintances, including Ottocaro Weiss, an Italian he befriended in Zürich in 1915:

His favorite war story was sheer burlesque. One evening when Ottocaro Weiss had been discussing Freud’s theory that humor was the mind’s way of securing relief, through a short cut, for some repressed feeling, Joyce replied gaily, ‘Well, that isn’t true in this case.’ He then told his father’s story of Buckley and the Russian General, which was to be mentioned in Ulysses and to wind in and out of Finnegans Wake. Buckley, he explained, was an Irish soldier in the Crimean War who drew a bead on a Russian general, but when he observed his splendid epaulettes and decorations, he could not bring himself to shoot. After a moment, alive to his duty, he raised his rifle again, but just then the general let down his pants to defecate. The sight of his enemy in so helpless and human a plight was too much for Buckley, who again lowered his gun. But when the general prepared to finish the operation with a piece of grassy turf, Buckley lost all respect for him and fired. Weiss replied, ‘Well, that isn’t funny.’ Joyce told the story to other friends, convinced that it was in some way archetypal. [Footnote: Joyce had some difficulty working the story into Finnegans Wake, and in Paris said to Samuel Beckett, ‘If somebody could tell me what to do, I would do it.’ He then narrated the story of Buckley; when he came to the piece of turf, Beckett remarked, ‘Another insult to Ireland.’ This was the hint Joyce needed; it enabled him to nationalize the story fully ...] (Ellmann 398)

As Ellmann notes, it was Joyce’s original intention to include this anecdote—and the other one too—in Ulysses, specifically in the Cyclops episode, which is set in Barney Kiernan’s pub. As it happened, Cyclops took a different turn and Joyce never managed to fit them in. He did, however, set them up, as it were, earlier in the novel. In the Aeolus episode, mention is made of the assassination of a Russian General Bobrikov in Finland, an historical event which did indeed take place on the morning of the original Bloomsday, 16 June 1904 (though Bobrikov only died of his wounds the following day):

The professor, returning by way of the files, swept his hand across Stephen’s and Mr O’Madden Burke’s loose ties.

— Paris, past and present, he said. You look like communards.

— Like fellows who had blown up the Bastille, J.J. O’Molloy said in quiet mockery. Or was it you shot the lord lieutenant of Finland between you? You look as though you had done the deed. General Bobrikoff. (Joyce 1922:129)

And earlier in the day, in Calypso, Bloom wonders whether he will meet a certain hunchbacked Norwegian captain:

There’s whatdoyoucallhim out of. How do you? Doesn’t see. Chap you know just to salute bit of a bore. His back is like that Norwegian captain’s. Wonder if I’ll meet him today. (Joyce 1922:58)

Unwilling to waste such good material, Joyce preserved the notes he had accumulated on these two anecdotes. In the months after the publication of Ulysses, they found their way into two of the earliest of the Finnegans Wake notebooks: VI.A (Scribbledehobble) and VI.B. He was determined to use them in his next work.

And, boy, did he use them! The two tales, now inflated to epic status, became the centrepieces of II.3, The Scene in the Public, which is the Wake’s counterpart of the Cyclops episode in Ulysses.

Incidentally, Frederick A Buckley was a real person: a Dubliner, a raconteur, a collector of rates, a skilled marksman, and a colleague of Joyce’s father John Stanislaus Joyce. He is believed to be the only begetter of The Story of How Buckley Shot the Russian General. But the anecdote is just a tall tale: Fred Buckley was only eight years old when the Crimean War ended.

Freud and Joyce

James Joyce had an ambivalent attitude towards Sigmund Freud. He could not ignore so influential a scholar of the unconscious mind, not to mention the author of the definitive investigation of the dreamworld—two subjects at the very heart of Finnegans Wake. On the other hand, he was repelled by Freudian psychoanalysis—which Joyce disparaged but found useful is Ellmann’s comment (393)—being slightly more intrigued by Carl Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious. Nevertheless, there was surely something to the fact that Joyce and Freud shared the same name ... sort of: Joyce comes from the Norman French Joyeux, which means joyous, while Freud comes from the German Freude, which means joy. A Wakean association, perhaps.

It is also curious that Joyce’s recounting of the story of Buckley and the Russian General to Ottocaro Weiss was prompted by Weiss’s comments on Sigmund Freud:

One evening when Ottocaro Weiss had been discussing Freud’s theory that humor was the mind’s way of securing relief, through a short cut, for some repressed feeling ... (Ellmann 398)

The work to which Weiss is alluding is Der Witz und seine Bezeihung zum Unbewußten [Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious], in which Freud briefly explores the psychological role played by jokes in human life. Among the many jokes analyzed by Freud in this short book are two that concern the Duke of Wellington, both recorded by the German historian of art and culture Jacob von Falke:

So, too, the joke repeated by Von Falke: ‘Is this the place where the Duke of Wellington spoke those words?’ — ‘Yes, it is the place; but he never spoke the words.’ (Freud 1662)

Von Falke (1897, 271) brought home a particularly good example of representation by the opposite from a journey to Ireland, an example in which no use whatever is made of words with a double meaning. The scene was a wax-work show (as it might be, Madame Tussaud’s). A guide was conducting a company of old and young visitors from figure to figure and commenting on them: ‘This is the Duke of Wellington and his horse’, he explained. Whereupon a young lady asked: ‘Which is the Duke of Wellington and which is his horse?’ ‘Just as you like, my pretty child,’ was the reply. ‘You pays your money and you takes your choice.’ (Freud 1670)

The first of these jokes revolves around the “legend” that at a crucial point in the Battle of Waterloo, the Duke turned to the Foot Guards, whom he had been holding in reserve, and said: “Up, Guards, and at ’em!”. Both jokes are mined to exhaustion in Finnegans Wake. Even Freud’s farfetched analysis of the second joke is relevant to the Museyroom episode:

The reduction of this Irish joke would be: ‘Shameless the things these wax-work people dare to offer the public! One can’t distinguish between the horse and its rider! (Facetious exaggeration.) And that’s what one pays one’s money for!’ This indignant exclamation is then dramatized, based on a small occurrence. In place of the public in general an individual lady appears and the figure of the rider is particularized: he must be the Duke of Wellington, who is so extremely popular in Ireland. But the shamelessness of the proprietor or guide, who takes money out of people’s pockets and offers them nothing in return, is represented by the opposite—by a speech in which he boasts himself a conscientious man of business, who has nothing more closely at heart than regard for the rights which the public has acquired by its payment. And now we can see that the technique of this joke is not quite a simple one. In so far as it enables the swindler to insist on his conscientiousness it is a case of representation by the opposite; but in so far as it effects this on an occasion on which something quite different is demanded of him—so that he replies with business like respectability where what we expect of him is the identification of the figures—it is an instance of displacement. The technique of the joke lies in a combination of the two methods. (Freud 1670)

Throughout the Museyroom episode there is a conflation of the Duke of Wellington and his horse Copenhagen. The Big White Horse becomes Wellington’s Big Wide Arse, as though the Duke is a horse’s arse. Another legendary “quote” from the Duke is relevant here:

If a gentleman happens to be born in a stable, it does not follow that he should be called a horse. )

As quoted in Genetic Studies in Joyce (1995) by David Hayman and Sam Slote. Though such remarks have often been quoted as Wellington’s response on being called Irish, the earliest published sources yet found for similar comments are those about him attributed to an Irish politician:

“The poor old Duke! What shall I say of him? To be sure he was born in Ireland, but being born in a stable does not make a man a horse.”

Daniel O’Connell, in a speech (16 October 1843), as quoted in Shaw’s Authenticated Report of the Irish State Trials (1844), p. 93.

Wikiquote

Whoever said it, Joyce makes free use of it throughout Finnegans Wake. It is particularly piquant as it includes not only an insult to Ireland (cf Beckett’s comment on the Russian General’s use of the sod of turf) but also suggests that the Duke of Wellington may be a new Christ, another not-horse who was reputedly born in stable. Incidentally, one might recall how prominent our equine friends were in Ulysses, from the Wooden Horse of Troy to Throwaway to Stephen’s Horseness is the whatness of allhorse. It is also fortuitous that Napoleon’s commander in the field at the Battle of Waterloo was Marshal Ney—get it?

With his remarks about money exchanging hands and the public being represented by a single young woman, Freud inadvertently introduces a meretricious element to the tale—one which Joyce was not slow to exploit. In the Museyroom episode, this young woman becomes the subject of yet another legendary quote of the Duke’s. Wikiquote, has it that it was this way:

Publish and be damned.

His response in 1824 to John Joseph Stockdale who threatened to publish anecdotes of Wellington and his mistress Harriette Wilson, as quoted in Wellington—The Years of the Sword (1969) by Elizabeth Longford. This has commonly been recounted as a response made to Wilson herself, in response to a threat to publish her memoirs and his letters. This account of events seems to have started with Confessions of Julia Johnstone In Contradiction to the Fables of Harriette Wilson (1825), where she makes such an accusation, and states that his reply had been “write and be damned”. Wikiquote

But Joyce prefers the version George Bernard Shaw deploys in his early play Mrs Warren’s Profession:

“The old Iron Duke didnt throw away fifty pounds: not he. He just wrote: ‘Dear Jenny: publish and be damned! Yours affectionately, Wellington.’.” (Shaw )

Mrs Warren’s Profession was prostitution. I don’t know where Shaw found the name Jenny (perhaps it’s an allusion to Jenny Patterson, the older woman who took his own virginity on his twenty-ninth birthday) but it is curiously appropriate in this context: a jenny is a female donkey, and Jennifer is derived from Guinevere, the name of King Arthur’s adulterous wife. Wellington was never a king, but his given name was Arthur!

References

- Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, Second Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1982)

- Sigmund Freud, James Strachey (translator), Freud: Complete Works, Compiled by Ivan Smith (2000, 2007, 2010, 2011)

- Jacob Von Falke, Lebenserinnerungen [Memoirs], Georg Heinrich Meyer (1897)

- James Joyce, Ulysses, Shakespeare and Company, Paris (1922)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

- Giambattista Vico, Goddard Bergin (translator), Max Harold Fisch (translator), The New Science of Giambattista Vico, Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY (1948)

Image Credits

- Panorama de la Bataille de Waterloo (Detail): Louis Dumoulin (artist), © 2012-2019 Au goût d’Emma [Emmanuelle Hubert], Fair Use

- James Joyce (Zürich 1915): Ottocaro Weiss (photographer), University at Buffalo Libraries, Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

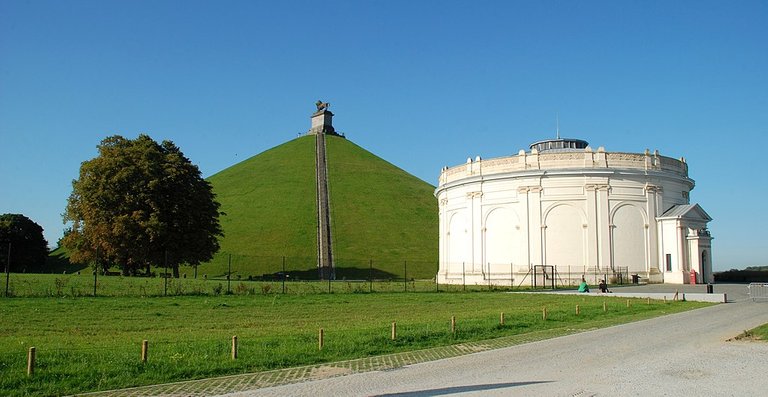

- The Rotunda and Lion’s Mound on the Waterloo Battlefield: © EmDee, Creative Commons License

- Sigmund Freud: Ludwig Grillich (photographer), Public Domain

- Copenhagen: The Duke of Wellington’s Horse at Waterloo: James Ward (artist), Public Domain

- The Wellington Monument in the Phoenix Park: Robert French (photographer), National Library of Ireland, The Lawrence Photograph Collection, Public Domain

Useful Resources

- James Joyce: Online Notes

- Joyce Tools

- FWEET

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- James Joyce Digital Archive

- Annotated Finnegans Wake (with Wakepedia)

- From Swerve of Shore to Bend of Bay

Very good written excellent friend, thank you for your contribution to this great community

Fantastic work friend friend congratulations is a very interesting post good job greetings

Great writing bro. Love you so much

The Rotunda and Lion’s Mound on the Waterloo Battlefield is nice