A couple of days ago, I shared some surprisingly good news about Africans getting out of extreme poverty - the news goes completely against what we expect from our daily feed from the media. Today I'll add a couple of thoughts to put the news into even better future context.

The news is so good that this little girl might not comprehend a world where de facto we assume Africa is a place of misery and suffering.

I'm warning you, it's really good news

Frankly, I never thought I'd see this in my lifetime (yes, I plan on living well past the year 2030).

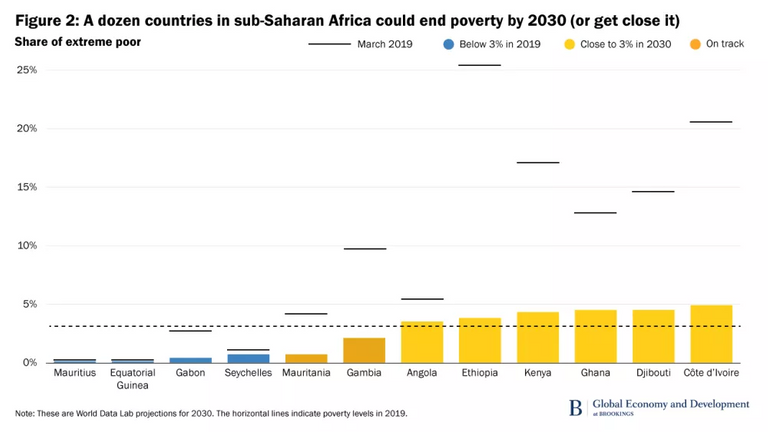

For the sharp-eyed, this graph captures what you read in last Saturday's post. It resets the paradigm of hopelessness - these countries have a real shot at achieving a better standard of living for their citizens.

As Brookings put it:

If current trends stay as they are, Ethiopia and Kenya are projected to achieve SDG 1 by 2032; Ghana, Angola, and Côte d’Ivoire in 2033; while Djibouti will follow a year later in 2034.

As the global poverty narrative shifts towards Africa, including at this year’s U.N. General Assembly, it seems clear that ending extreme poverty by 2030 seems almost impossible at this point. However, it is important to note that the continent has turned the corner and poverty levels could come down substantially over the next decade.

Did I mention it's good news? Just want to be clear

That these people will be out of extreme poverty means a few important things for them and their families.

- the likelihood of children in their families dying from disease or malnutrition before the age of 5 will plummet, as their access to quality food in enough quantity and the possibility of living in more hygienic conditions will increase

- the likelihood of these same children having access to education will increase, as their families will have more funds available to spend on educational expenses such as fees, uniforms and class materials

- the women are likely to have less children (sounds counter-intuitive, but as people prosper generally birthrates decrease)

- they will also likely have these children later in their lives

- that will give them a shot at getting an education themselves, becoming more literate and accessing more empowering work opportunities

- there's a chance these women will suffer less violence at the hands of men in their communities.

And the list goes on.

However, some necessary sobering thoughts

As Our World in Data reminds us, becoming "not poor" is generally not a binary experience (unless a person wins the lottery, I suppose) - people who have access to more money don't usually experience a visit from a fairy godmother who waves a magic wand and poof!, the world becomes beautiful for them.

...the smooth relationship between income and subjective well-being highlights the difficulties that arise from using a fixed threshold above which people are abruptly considered to be non-poor. In reality, subjective well-being does not suddenly improve above any given poverty line. This makes using a fixed poverty line to define destitution as a binary 'yes/no' problematic. Therefore, while the International Poverty Line is useful for understanding the changes in living conditions of the very poorest of the world, we must also take into account higher poverty lines reflecting the fact that living conditions at higher thresholds can still be destitute.

Which means it's good news when these countries cross the International Poverty Line, but it's not the whole story.

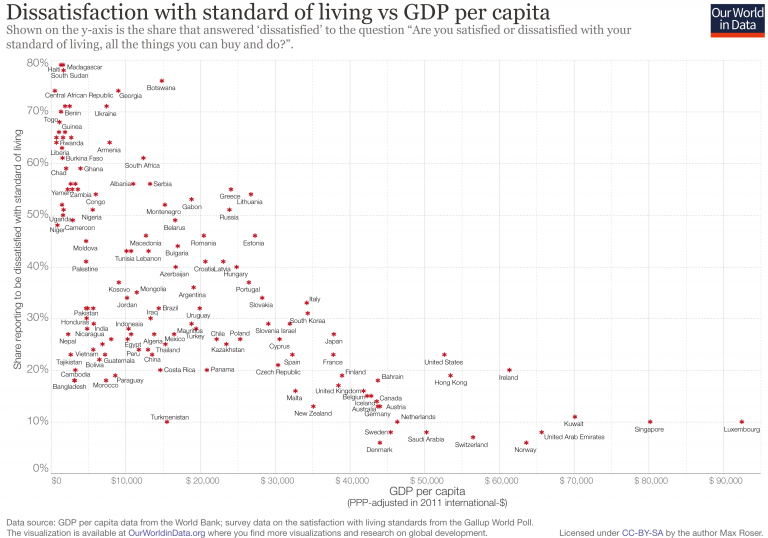

Let's take a look at global perceptions of prosperity

It's quite interesting to look at how dissatisfied people in, say, Bangladesh, Cambodia or Vietnam are compared with how dissatisfied people in South Africa, Madagascar and South Sudan are with their standard of living. Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam are each characterised by much lower Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita than South Africa, and they're pretty much on par with Madagascar and South Sudan for GDP per capita, which puts them at the far left of the graph...but less than 30% dissatisfied, while the other three countries sit somewhere between 60% and 80% dissatisfied.

So it can't be just about how much money you have to get by. It must be more complex than that. What factors do you think influence people's satisfaction with their standard of living?

References

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2019/03/28/poverty-in-africa-is-now-falling-but-not-fast-enough/?utm_campaign=Brookings%20Brief&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=71274287

https://ourworldindata.org/extreme-poverty

Team South Africa banner designed by @bearone

It would be amazing to see Sub-Saharan Africa uplifted. In South Africa the dissatisfaction definitely is lack of facilities to good education, crime and rampant poverty.

Certain things such as running water and electricity should have reached a lot more people by now. Housing in shacks is not a place to live!

If there is a silver lining under the dark cloud, let it be people receive what was promised many years ago.

I couldn't agree more with you, @joanstewart! I thought I'd take a look at the Gini coefficients for those six countries I mentioned and see the extent to which dissatisfaction with standard of living correlates with inequality. I also think visible, rampant corruption and its products - the ones you've mentioned above - have a major role to play in that dissatisfaction.

South Africans simply deserve better than what they're getting. They were sold a bill of goods that they were getting a democracy along with its fruits that would overturn a great historical wrong, and instead they got, well...this.

After the last ten years I think most are gobsmacked and confused. Swan song of politicians in many countries....

Sigh....