FREE ORIGINAL RESOURCE TO DOWNLOAD for you lovely steemians!

Information on multidisciplinary management of neuropathic pain in diabetes (see end of article for download links and images you can download!)

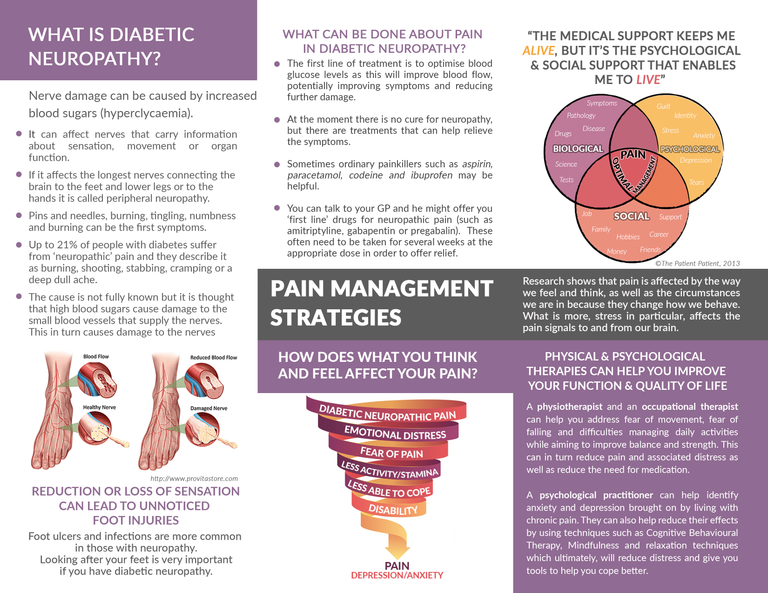

I am pleased to offer you all a patient information resource regarding neuropathic pain in diabetes. Currently an estimated 4.5 million or 6.5% of people in the UK live with Diabetes Mellitus (DM) (NHS, 2016). Within this group, research has estimated that 43% suffer diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) and that 10 - 24% of sufferers experience pain related to diabetic neuropathy (DPN-P) (Argoff, Cole, Fishbain, & Irving, 2006; Van Acker, et al., 2009).

Unfortunately neuropathic pain in general remains historically under-recognised and undertreated (Herman & Kennedy, 2005; Smith, Lee, Price, & Baranowski, 2013; Sobhy, 2016). Moreover, evidence suggests that certain individuals might not relate peripheral pain with diabetes so will not report it (Davies & Coppini, 2012). Therefore, raising its profile might help provide timely management strategies and, to facilitate this, the leaflet contains information about the prevalence and pathophysiology of the condition in very simple terms. It also includes information on initial medical treatment and self-management, but more importantly, it highlights the relevance of psychosocial aspects and interventions which I will explore further in this letter.

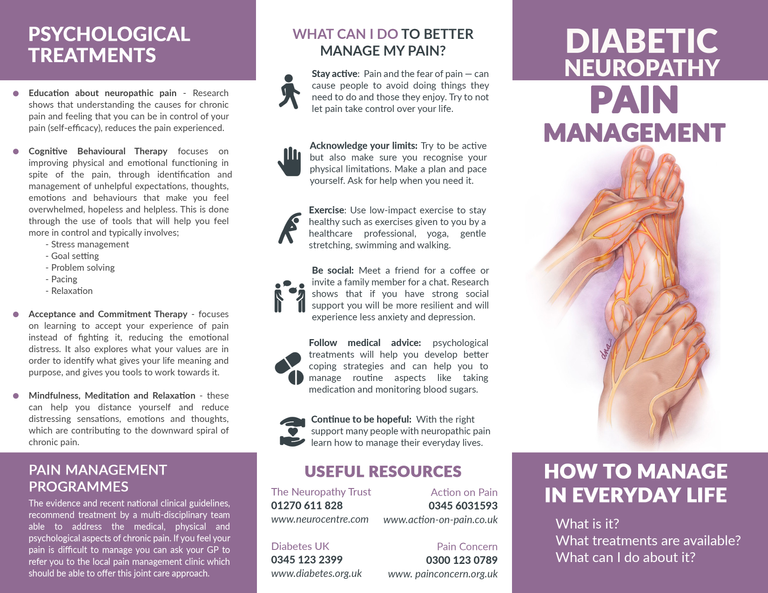

While pharmacological approaches are the first line of treatment, research has found that less than 50% of patients benefit from them, and those only experience a 30-40% improvement (Turk, Audette, Levy, Mackey, & Stanos, 2010). This suggests that factors other than biological pathology are at play, namely psychological and social, in line with the biopsychosocial model of pain (Wade & Halligan, 2017). Furthermore, many international guidelines have advocated the biopsychosocial approach in chronic pain management (WHO, 2002; Dowell, Haegerich, & Chou, 2016) and, for example, the British Pain Society recommend the parallel use of self-help, information resources and psychological interventions for neuropathic pain (Smith, Lee, Price, & Baranowski, 2013). There are several reasons for this.

Firstly, consistent evidence suggests that DPN alone increases the incidence of anxiety, depression, poor sleep and reduced quality of life (QoL) in diabetes patients (Bai, et al., 2017; Bartoli, et al., 2016; Geelen, et al., 2017). Furthermore, this effect is amplified in cases where pain is present, suggesting that DPN-P independently affects mental health and quality of life (Geelen, et al., 2017; Turk, Audette, Levy, Mackey, & Stanos, 2010; Van Acker, et al., 2009). In particular, researchers conclude that the association between DPN and negative affect is mediated by perceptions of symptom unpredictability, lack of control (self-efficacy), social role and activity restriction (Umarov, Prokhorova, & Mamatkulov, 2016). However, the causality of the relationship is unclear and it has been suggested that pre-morbid psychiatric and psychosocial issues are responsible for the pain experienced (Turk, Audette, Levy, Mackey, & Stanos, 2010). It is because of this inherent complexity that the use of psychological therapies and multidisciplinary teams, with specialist assessment and treatment skills, is recommended in the management of DPN-P.

Additionally, psychosocial issues can affect self-management of diabetes itself, thus creating a vicious cycle of progressively deteriorating DPN-P and quality of life (Pibernik-Okanović, Ajduković, Lovrenčić, & Hermanns, 2011). For example, a qualitative study by Geelen et al. (2017) found that patients with DPN suffer from various fears, such as fear of pain, falling, fatigue and movement which were shown to be associated with reduced quality of life and increased disability. More importantly, they found that fear of low blood sugar events led patients to avoid using blood glucose management strategies appropriately, which in turn resulted in these individuals maintaining high blood sugars with their associated risks such as increased nerve damage. These findings are consistent with the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain which proposes that fear of certain outcomes, which are interpreted as threatening, will lead to non-participation with treatment and daily activities, resulting in a vicious cycle of catastrophic thinking, avoidance, further pathology and increasing disability (Lethem, Slade, Troup, & Bentley, 1983). Thankfully these issues can be addressed through psychological treatments some of which are outlined in the leaflet.

For example, psychoeducation aims to improve self-efficacy by providing patients with information about their condition and skills within a counselling framework, thus gaining understanding, problem-solving strategies and goal setting skills (Authier, 1977). To support this, recent research in chronic pain has found that a combination of psychoeducation and physical therapy results in an evolution from passive to active coping strategies partly due to the patients change in perception about their pain and the effectiveness of interventions offered (Vanhaudenhuyse, et al., 2017).

Alternatively, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) which is widely utilised, places the emphasis on helping individuals with pain to realize that self-management is possible through learning to conceptualise their pain (cognitive restructuring) as well as acquiring proactive management skills (operant learning). CBT typically combines psychoeducation, stress management, problem-solving, goal setting, pacing of activities and relaxation (Turk, Audette, Levy, Mackey, & Stanos, 2010). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis of the literature have concluded that CBT in chronic pain results in significant and moderate changes in pain experience, cognitive coping and appraisal and expression of pain (Morley, Eccleston, & Williams, 1999). However, similar reviews concerning neuropathic pain have been inconclusive due to the methodological difficulties in defining and measuring neuropathic pain (Wetering, Lemmens, Nieboer, & Hujisman, 2010). Nevertheless, CBT has shown effectiveness in reducing depressive symptoms in diabetic patients as well as improving self-management and treatment compliance (Pibernik-Okanovic, Begic, Ajdukovic, Andrijasevic, & Metelko, 2009).

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) on the other hand, focuses on accepting pain, rather than fighting it, and targets ineffective control strategies and experiential avoidance. Patients are taught how to stay in contact with unpleasant emotions, sensations, and thoughts through mindfulness, and core values are identified and targeted to facilitate psychological flexibility (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999). Research has been inconclusive on its benefits over CBT (Veehof, Schreurs, & Bohlmeijer, 2011), but it provides an alternative for those that find CBT unhelpful and has been shown to result in higher satisfaction with treatment (Wetherell, et al., 2011)

In conclusion, DPN-P is debilitating and has effects on the mental health and quality of life of diabetes patients. The evidence for the existence of psychosocial components within neuropathic pain is clear. However, better recognition and management beyond the pharmacological options is required, and the use of psychological therapies and multidisciplinary teams is recommended.

You can dowload the .PNG images below or dowload as a PDF here!

References

Argoff, C. E., Cole, B. E., Fishbain, D. A., & Irving, G. A. (2006). Diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain: clinical and quality-of-life issues. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 81(4), S3-S11.

Authier, J. (1977). "The psychoeducation model: Definition, contemporary roots and content.". Canadian counsellor, 15-22.

Bai, J. W., Lovblom, L. E., Cardinez, M., Weisman, A., Farooqi, M. A., Healpern, E. M., . . . Keenan, H. A. (2017). Neuropathy and presence of emotional distress and depression in longstanding diabetes: Results from the Canadian study of longevity in type 1 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.05.002

Bartoli, F., Carrà, G., Crocamo, C., Carretta, D., La Tegola, D., Tabacchi, T., . . . Clerici, M. (2016). Association between depression and neuropathy in people with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31, 829-836. doi:10.1002/gps.4397.

Crombez, G., Eccleston, C., Van Damme, S., Vlaeyen, J. W., & Karoly, P. (2012). Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: the next generation. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 475-483.

Davies, S., & Coppini, D. (2012). Production of an information leaflet on diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Journal of Diabetes Nursing, 16(7), 276-280.

Dowell, D., Haegerich, T. M., & Chou, R. (2016). CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States. Journal of the American Medical Association, 315(15), 1624-1645.

Geelen, C. C., Smeets, R. J., Schmitz, S., van den Bergh, J. P., Goossens, M. E., & Verbunt, J. A. (2017). Anxiety affects disability and quality of life in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy. European journal of pain, 1-10.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. Guilford Press.

Herman, W. H., & Kennedy, L. (2005). Underdiagnosis of peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care, 28(6), 1480-1481.

Lethem, J., Slade, P. D., Troup, J. D., & Bentley, G. (1983). Lethem, J., Slade, P. D., Troup, J. D. G., & Bentley, G. (1983). Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception—I. Behaviour research and therapy, 21(4), 401-408.

Morley, S., Eccleston, C., & Williams, A. (1999). Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain, 80(1), 1-13.

NHS. (2016, October). Quality and Outcomes Framework 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2017, from NHS Digital: http://www.content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB22266/qof-1516-rep-v2.pdf

Pibernik-Okanović, M., Ajduković, D., Lovrenčić, M. V., & Hermanns, N. (2011). Does treatment of subsyndromal depression improve depression and diabetes related outcomes: protocol for a randomised controlled comparison of psycho-education, physical exercise and treatment as usual. Trials, 12(1), 1-8.

Pibernik-Okanovic, M., Begic, D., Ajdukovic, D., Andrijasevic, N., & Metelko, Z. (2009). Psychoeducation versus treatment as usual in diabetic patients with subthreshold depression: preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 10:78, 1-9.

Smith, B. H., Lee, J., Price, C., & Baranowski, A. P. (2013). Neuropathic pain: a pathway for care developed by the British Pain Society. British journal of anaesthesia, 111(1), 73-79.

Sobhy, T. (2016). The Need for Improved Management of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy in Primary Care. Pain Research and Management, 1-4. doi:10.1155/2016/1974863

Turk, D. C., Audette, J., Levy, R. M., Mackey, S. C., & Stanos, S. (2010). Assessment and treatment of psychosocial comorbidities in patients with neuropathic pain. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 85(3), S42-S50.

Umarov, A., Prokhorova, A., & Mamatkulov, E. (2016). Peripheral neuropathy and depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes. Endochrine Abstracts, 41 EP755. doi:10.1530/endoabs.41.EP755

Van Acker, K., Bouhassira, D., De Bacquer, D., Weiss, S., Matthys, K., Raemen, H., . . . Colin, I. M. (2009). Prevalence and impact on quality of life of peripheral neuropathy with or without neuropathic pain in type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients attending hospital outpatients clinics. Diabetes & metabolism, 35(3), 206-213.

Vanhaudenhuyse, A., Gillet, A., Malaise, N., Salamun, I., Grosdent, S., Maquet, D., . . . Faymonville, M. (2017). Psychological interventions influence patients' attitudes and beliefs about their chronic pain. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.09.001

Veehof, M. M., Schreurs, K. M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2011). Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain, 152(3), 533-542.

Wade, D. T., & Halligan, P. W. (2017). The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clinical Rehabilitation, 31(8), 995-1004. doi:10.1177/0269215517709890

Wetering, E. J., Lemmens, K. M., Nieboer, A. P., & Hujisman, R. (2010). Cognitive and behavioral interventions for the management of chronic neuropathic pain in adults–a systematic review. European Journal of Pain, 14(7), 670-681.

Wetherell, J. L., Afari, N., Rutledge, T., Sorrell, J. T., Stoddard, J. A., Petkus, A. J., . . . Hmapton Atkinson, J. (2011). A randomized, controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain, 152(9), 2098-2107. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.05.016

WHO. (2002). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Retrieved July 21, 2017, from World Health Organisation: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf?ua=1

@originalworks

The @OriginalWorks bot has determined this post by @olayar to be original material and upvoted it!

To call @OriginalWorks, simply reply to any post with @originalworks or !originalworks in your message!

To nominate this post for the daily RESTEEM contest, upvote this comment! The user with the most upvotes on their @OriginalWorks comment will win!

For more information, Click Here!

The only thing that interferes with my learning is my education.

- Albert Einstein