The Restoration of Ancient History is a paper delivered in November 1994 by Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen in Germany, at a symposium in Portland, Oregon. This paper questions the conventional chronology of ancient history and offers in its place a radical reconstruction—the so-called Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the principal architect. In this series of articles, we are taking a closer look at the evidence cited in this paper in favour of Heinsohn’s new chronology:

In this article we will continue our survey of Part 3 of Heinsohn’s lecture: Archaeologically-missing history and historically-unexpected archaeology in major areas of antiquity.. In this section, Heinsohn reviews a long list of cases where archaeologists have discovered major discrepancies between the archaeology of the Ancient World and its history as recorded by the Classical historians. These discrepancies fall into two broad categories:

Excavations in which the archaeologists failed to find strata that the recorded history had led them to expect.

Excavations in which the archaeologists uncovered strata that did not correspond to any cultures or civilizations in the recorded history.

Central Asia

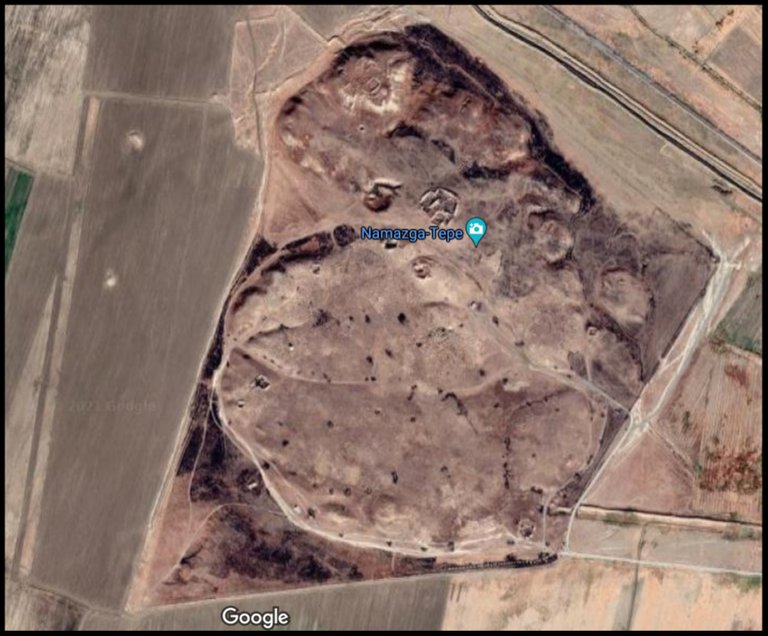

Heinsohn’s reconstruction of ancient chronology is not restricted to the heartland of the Ancient World. He also includes in his study two sites in Central Asia, whose stratigraphies are among the finest in the region: Namazga-Tepe and Altyn-Tepe, both of which lie in southern Turkmenistan.

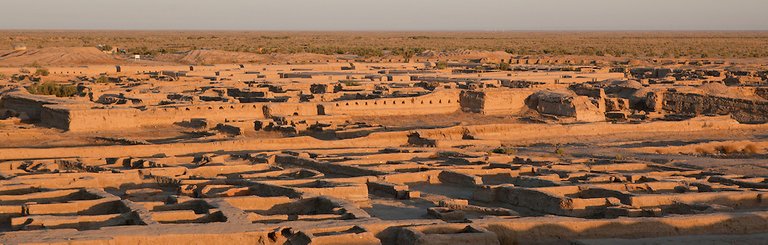

These are just two of several forgotten cities from this part of the Ancient World. Before dramatic changes in climate turned this fertile and productive region into a desert wasteland, Central Asia had been home to a flourishing urbanized civilization, the extent and significance of which are only slowly coming to light. According to conventional archaeology, the so-called Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex reached its peak during the Middle Bronze Age, which is conventionally dated to the second millennium BCE.

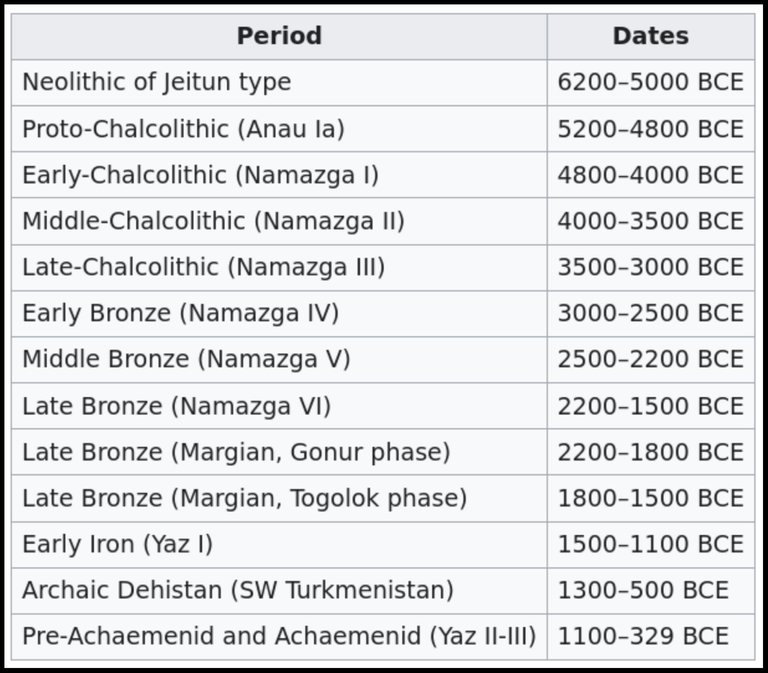

Namazga-Tepe once lay in the Persian satrapy of Parthia. Excavations at the site have been ongoing since 1949 and the well-developed stratigraphy has become the basis for the conventional chronology of the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age in this part of the world:

Namazga went into decline during the Late Bronze Age and survived only as a small village. It was finally abandoned during the Achaemenid Period (P L Kohl, Central Asia: Palaeolithic Beginnings to the Iron Age).

Altyn-Tepe is a similar site in Turkmenistan, located 100 km southeast of Namazga-Tepe. Archaeological excavations began in 1965 and uncovered about 30 m of strata dating back to the Neolithic. The city reached its peak during the Bronze Age, when it had cultural and trading links with the cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. It was abandoned around the same time as the Harappan cities, possibly due to soil exhaustion and climate change:

Altin Tepe reached its most flourishing stage at the end of the 3rd-early 2nd millennium B.C. (complex of the Namazga V type), when it was a settlement of the early urban type ... Altin Tepe was closely linked with the contemporary ancient East. In architecture and toreutics, traits of Mesopotamian influence have been noted; vessels of black clay have been found originating from northwestern Iran (Ḥeṣār, Shah Tepe), as well as ivory artifacts imported from the Harappa settlements of Hindustan. The culture of Altin Tepe reflects the process of the formation in southern Turkmenistan of a local civilization of the Ancient Oriental type. The abandonment of the site appears to have been connected with the exhaustion of the soil and climatic changes. (Encyclopaedia Iranica)

Heinsohn’s Reconstruction

Heinsohn has noted how the archaeology of this region reaches its apogee in the Late Bronze Age and then peters out, leaving a gap of almost a millennium before Central Asia was incorporated into the Achaemenid Empire. But why would the Persians concern themselves with a sparsely populated wasteland?

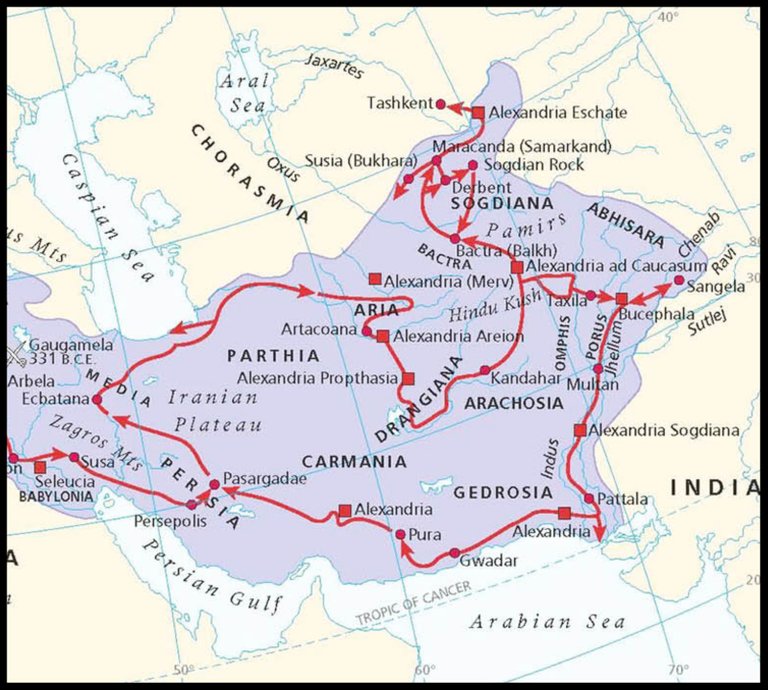

Students of Ancient Central Asia are stunned by the archaeological absence of the history of the land bridge between the Near East and India/China, from Ninos down to the end of the Persian Empire, which was taken for granted for nearly two and a half millennia. They are convinced that there was no urban Central Asia to talk of when Alexander the Great conquered it. Yet, they take pride in the discovery of a steppe bronze and iron high culture which preceded China's by l500 and more years. On the other hand, they are bewildered to have found Achaemenid looking, i.e., post-550 pottery as early as -l500. They are even more puzzled by the similarity of the material culture of -2000 to the material culture of -330. Irrigation canals of -1800 are reused 1500 years later. (Heinsohn)

In Herodotus’s list of the twenty provinces, or satrapies, of the Persian Empire, the sixteenth comprised the Parthians, Chorasmians, Sogdians, and Arians and paid an annual tribute of 390 talents of silver. (Sélincourt 244). Even Alexander the Great considered this area worthy of conquest. Between 330 and 327 BCE, he campaigned in this region, taking about three years to subdue it. One of the ancient cities of Turkmenistan, Merv, was actually known as Alexandria in Margiana for a time. According to Pliny the Elder, it was founded by Alexander (Natural History 6:18). Clearly, Central Asia was seen by both the Persians and the Macedonians as worthy of conquest.

Heinsohn has realigned the chronology of the region to close up the embarrassing gap in the archaeology. The high point of Central Asia’s ancient civilization, he believes, occurred during the Achaemenid Era:

| Conventional | Stratum | Heinsohn |

|---|---|---|

| 4000-2900 | Namazga I-III | 1150-750 |

| 2900-2300 | Namazga IV | 750-630 |

| 2300-1850 | Namazga V | 630-520 |

| 1850-329 | Namazga VI, Yaz I-III | 520-329 |

Discussion

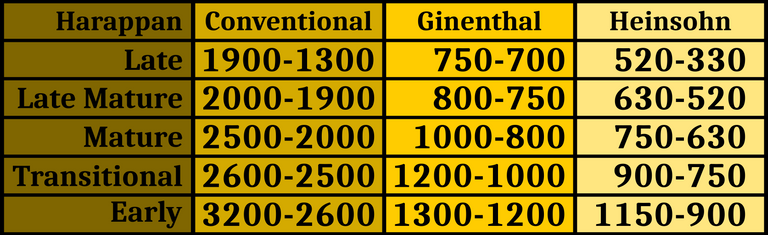

In an earlier article on the Indus Valley Civilization, we saw that the collapse of the Harappan cities was precipitated by a dramatic shift in climate—Klimasturz—which turned what had been productive agricultural land into a barren wasteland. According to Charles Ginenthal, this Klimasturz occurred around or shortly after 800 BCE. Heinsohn, however, believes that the climatic crisis which precipitated the collapse of both urbanized civilizations—Indus Valley and Central Asia—occurred much later than this, during the Achaemenid Period. It may even have played a pivotal role in the collapse of the Persian Empire.

In that earlier article, we read in Strabo’s Geography an account of Aristobulus of Cassandreia’s journey down the Indus Valley in 329 BCE, during Alexander the Great’s campaign in the region. Aristobulus reported seeing more than a thousand deserted cities (Strabo 15:1:19). These were obviously the recently abandoned cities of the Harappans. But how recently had they been abandoned? It sounds as though Aristobulus is referring to cities that had been abandoned very recently.

The conventional date for the collapse of the Harappan Civilization (c 1200 BCE, or more than a millennium before Aristobulus’s time) seems much too remote to be sustainable. Surely after a millennium, the cities would have been completely covered over by wind-blown, or aeolian, deposits. But if Ginenthal’s date of c 800 BCE is correct, this means that the cities had been lying abandoned for almost half a millennium. Is not this also quite a stretch? How long does it take for aeolian deposits to completely bury cities abandoned to a dry and dusty environment?

If there was a catastrophic climate change in the latter part of the Achaemenid Period, this could explain why the Persian Empire was already in a state of collapse when Alexander the Great launched his invasion. It has always baffled historians how a Macedonian army of only 32,000 infantry and 4500 cavalry (Diodorus Siculus 17:17:4) could march unopposed into Persia and take over the entire empire after only a handful of decisive battles. If the Persian Empire was already in a state of collapse due to environmental factors and internal dissensions, then the ease with which Alexander conquered it becomes less problematic.

According to the working hypothesis I proposed in an earlier article, the Indus Valley Civilization collapsed around 750-700 BCE. Some of its inhabitants migrated east into India, where they established the Vedic Civilization. Others migrated west, where they became the Medes and the Mitannians. I will have to modify this hypothesis if I wish to embrace Heinsohn’s thesis that the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization occurred just before Alexander’s campaign.

In the Heinsohn article on the Indus Valley Civilization, we saw that something dramatic occurred in the Indus Valley during the period known as the Transitional Harappan. Conventional archaeologists date this to 2600-2500 BCE. McIntosh summarizes this century in the following words:

Many settlements in the plains destroyed or abandoned, some rebuilt, many new settlements founded, probably including Mohenjo-daro; cultural integration; growing craft specialization; emergence of writing. (McIntosh 421)

Do these events imply that the Early Harappan state was conquered and colonized by foreign invaders? Or were these dramatic changes purely internal matters? Or were they triggered by some environmental upheaval? It is surely significant that this Transitional period was immediately followed by the golden age of the Indus Valley Civilization:

Cultural unity in Indus plains from Gujarat to northern Ganges-Yamuna doab; separate but related Kulli culture in southern Baluchistan; separate Late Kot-Diji culture in northern Indo-Iranian borderlands; well integrated internal distribution network; external trade with neighbors, Gulf and northern Afghanistan where Shortugai is founded; towns and cities; writing; craft specialization and industrial villages. (McIntosh 421)

The changes that occurred during the Transitional Harappan remain unexplained:

An understanding of how and why these changes took place is still elusive. (McIntosh 82)

In Heinsohn’s chronology, the Transitional Harappan occurred around 750 BCE. Perhaps this was the event that led to large-scale migration out of the Indus Valley, while Ginenthal’s Klimasturz did not take place until around 350 BCE? It may be possible, then, to accommodate both Heinsohn and Ginenthal.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volume 2, Forest Hills, NY (2008)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Frankfurt (1988)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

- Olivier Lecomte, Ulug Depe: 4000 Years of Evolution between Plain and Desert, in Historical and Cultural Sites of Turkmenistan, Turkmen State Publishing Service (2011)

- Jane R McIntosh, The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives, ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, CA (2008)

- Aubrey de Sélincourt (translator), Herodotus: The Histories, Penguin Books Limited, Harmondsworth, Middlesex (1954)

Image Credits

- The Ruins of Gonur-Tepe in Turkmenistan: © 2012 Deidre Sorensen, Fair Use

- Archaeological Sites in Turkmenistan: Map of Turkmenistan from CIA World Factbook, Public Domain

- Conventional Chronology of South Central Asia (Lecomte 223): © Olivier Lecomte, Fair Use

- Altyn-Tepe: © Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Turkmenistan, Fair Use

- Namazga-Tepe: © 2021 CNES/Airbus, Maxar Technologies, Fair Use

- Alexander’s Campaigns in Central Asia: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Anau, Turkmenistan: © Advantour, Fair Use

Online Resources