The Restoration of Ancient History is a paper delivered in November 1994 by Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen in Germany, at a symposium in Portland, Oregon. This paper questions the conventional chronology of ancient history and offers in its place a radical reconstruction—the so-called Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the principal architect.

Heinsohn recognizes four periods in the history of Mesopotamia before the conquests of Alexander the Great:

| Dates BCE | Upper Mesopotamia | Lower Mesopotamia |

|---|---|---|

| 540-330 | Persian Empire | Persian Empire |

| 620-540 | Empire of the Medes | Second Chaldaeans |

| 750-620 | Assyrian Empire | Assyrian Empire and Scythians |

| 1150-750 | Early Assyrians | First Chaldaeans |

In this article we will examine Part 7 of Heinsohn’s lecture: Synchronization of Ancient Eurasian Chronology with the Chronology of Ancient China. In this section, Heinsohn synchronizes the chronology of the Near East with the chronology of Ancient China. As the latter is based solely on archaeology, it supports the Short Chronology and confirms Heinsohn’s revised timeline for the ancient history of the Near East.

Heinsohn first notes the glaring discrepancies between the conventional chronologies of these two regions. China appears to have passed through the same cultural stages as the civilizations of the Near East, but always one or two millennia later than the latter:

When the vast stretch of land from Spain to the Indus-Valley entered the Bronze Age in the -4th millennium, China slowly moved into the New stone Age (Neolithic). Even the urban oases in the Central Asian and Afghan west of China, which entered the Bronze Age more or less simultaneously with Mesopotamia, failed to tempt the Chinese to adopt the technological level of their barbarian steppe neighbors. The mythology of western Asia spoke of theomachies (combats of celestial deities) as the triggers of high culture in the -3rd millennium, whereas China’s mythology did not do so for another 1,500 to 2,000 years. When the Eurasian land mass entered the Iron Age around -1600/-1400, China slowly moved into the Bronze Age. The Chinese waited an additional millennium—around -600/-400—before they could bring themselves to work iron. The Chinese did not seem to care about falling millennia behind. Yet, they were extremely careful not to miss a single developmental step in culture, religion and technology the neighbors in the west had gone through so much earlier. (Heinsohn)

Why did it take a thousand years for the knowledge of iron metallurgy to reach China? Heinsohn cites the Chinese-American archaeologist Kwang-chih Chang:

Whichever chronological scheme we may chose, the fact is that the known beginning of civilization in China is approximately a millennium and a half later than the initial phases of Near Eastern civilization. We can also take note of the fact that many essential elements of Chinese civilization, such as bronze metallurgy, writing, the horse chariot, human sacrifice, and so forth, had appeared earlier in Mesopotamia. Here, then, is the problem of East-West relationships all over again (Chang 1963:136)

Chang wrote these words in 1963 in the first edition of The Archaeology of Ancient China. Five years later, however, he expressed somewhat different views in a revised and enlarged edition of the book:

As Max Loehr pointed out, “An-yang represents, according to our present knowledge, the oldest Chinese metal age site, taking us back to ca. 1300 B.C. It displays no signs of a primitive stage of metal working but utter refinement. Primitive stages have, in fact, nowhere been discovered in China up to the present moment. Metallurgy seems to have been brought to China from outside.” The same held true for other elements of Shang civilization than metallurgy: writing, chariot warfare, bronze types, and so forth. Many scholars, principally because they thought that civilization came to China suddenly and without previous foundation, argued that it came as a result of diffusion from the Near East, where civilization emerged some fifteen hundred years before it came to China. Now, during the last seventeen years, with the revelation of Erh-li-kang, it appears that the foundation and primitive stages of Shang civilization elements have been discovered. (Chang 1968: 234)

But even if this is conceded, it still does not explain why these elements did not diffuse to China from the Near East centuries earlier. Why did it take the Chinese so long to discover for themselves how to work iron ore into steel when this knowledge had been available in the Near East for over a millennium. Chang noted that tombs dating from before the Warring States Period never contained iron artifacts, whereas every cemetery of the Warring States Period and the Han Dynasty invariably yielded some iron artifacts:

This is confirmed by the occurrence of iron objects in Period IV (early Warring States) of the Chung-chou Road sequence at Lo-yang. ... it seems likely that the emergence of iron metallurgy as a major industry for tool-making should be placed in the sixth century B.C. at the latest, although the techniques probably were not perfected and widely used until the fifth century, so far as archaeological evidence is concerned. (Chang 1968:313)

Heinsohn believes that the chronology that has been established for China by archaeologists on the ground in China is a better guide to the true chronology of the Bronze and Iron Ages in both east and west:

Yet, it is only the territory from Spain to the Indus-Valley which is dated by Mesopotamian king lists tied to the biblical birthdate of Abraham the Patriarch, China—like Mesoamerica—is dated independently. It, therefore, can be used as an interesting measuring rod for the true age of the beginning of the Bronze Age. (Heinsohn)

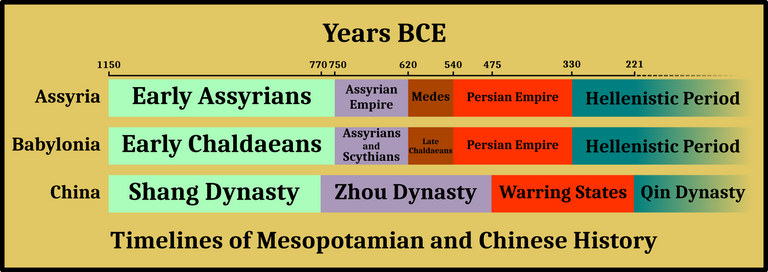

Heinsohn has not left us his precise timeline of Chinese history—his lecture notes for The Restoration of Ancient History include the phrase “do chart by hand”—but it is not too difficult to reconstruct it. One of the cornerstones of his revised chronology is that the great civilizations of the past arose more or less simultaneously around 1150 BCE. This synchronicity is due to the fact that earlier civilizations were all destroyed simultaneously by the global catastrophe that occurred at the end of the last glacial period (the Younger Dryas).

In Die Sumerer gab es nicht (1988), Heinsohn suggested that the fall of the Shang Dynasty and the rise of the Zhou Dynasty occurred around 770 BCE, quite close to the date he gives for the rise of the Assyrian Empire. Heinsohn has subsequently revised many of the ideas in that book, so I do not know if he still places the rise of the Zhou Dynasty around 770 BCE, but it is probably safe to assume that this is the case. The resulting timeline can be roughly synchronized with the timeline for the Near East if all the settlement gaps or hiatuses in Mesopotamian archaeology are removed. The Restoration of Ancient History concludes with the following words:

This author’s [ie Heinsohn’s] revision of ancient chronology claims that the gaps do not really represent a cessation of settlements but are due to unscholarly chronological constructs based on either Bible-fundamentalist premises of Assyriologists and/or pseudo-astronomical calculations of Egyptologists. Therefore, the years assigned to the gaps simply do not exist at all. The territories in India, Central Asia, Iran, Asia Minor, the Levant, Egypt and Mesopotamia proper, which have been dated via Abraham the Patriarch and false astronomical assumptions, must abandon the one-and-a-half-millennia allotted to their gaps—plus a few more centuries. The latter have to be deduced from the Early Dynasties whose levels nowhere provide the stratigraphic depth to reliably fill their conventional 600 years. Thus, the emergence of post-Neolithic high civilization does not come about before the turn to the 1st millennium B.C.E. This reduction brings China, the Ganges Valley as well as Mesoamerica (Olmecs) etc., into line with the rest of the world. (Heinsohn)

Here is my attempt at synchronizing Chinese and Mesopotamian chronology in accordance with Heinsohn’s 1994 lecture:

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Kwang-chih Chang, The Archaeology of Ancient China, First Edition, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT (1963)

- Kwang-chih Chang, The Archaeology of Ancient China, Enlarged and Revised Edition, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT (1968)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Frankfurt (1988)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

Image Credits

- Map of Shang China: © Times Books Limited, Geoffrey Barraclough (editor), The Times Atlas of World History, Third Edition, Page 62, Map 2, Hammond, Maplewood, NJ (1989), Fair Use

- K C Chang: © Boston University AsianARC, Fair Use

- Western Zhou Dynasty: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- China at the End of the Shang Dynasty: Georg Westermann (cartographer), Albert Herrmann, Historical and Commercial Atlas of China, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (1935), Public Domain

- Chronology of North China (Chang 1968:443): K C Chang, The Archaeology of Ancient China, Second Edition, Table 15, Page 443, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT (1968), Public Domain

Online Resources