Full disclosure: this is an edited, partially-rewritten version of a post I penned three years ago for the Steemit platform. I'm re-running it because it's a series I had fun researching, but also because I have a slew of new followers who might appreciate it. Upvotes are appreciated, but not required, and I'm using the #sbi-skip tag so as not to double-dip on rewards.

Shit happens. We're used to it. It's a daily occurrence. Sometimes, though, the world isn't content to merely dribble shit on you. Oh no. Sometimes the world unleashes a streaming, heaping torrent of shit on everyone and everything in a given area, and one of the nastiest ways it does this involves stuff blowing up. There's literally no spectacle of disaster that can't be made worse by adding explosions -- just ask Michael Bay -- but what's awesome on screen is considerably less awesome when it happens in real life. Need proof? Look no further than...

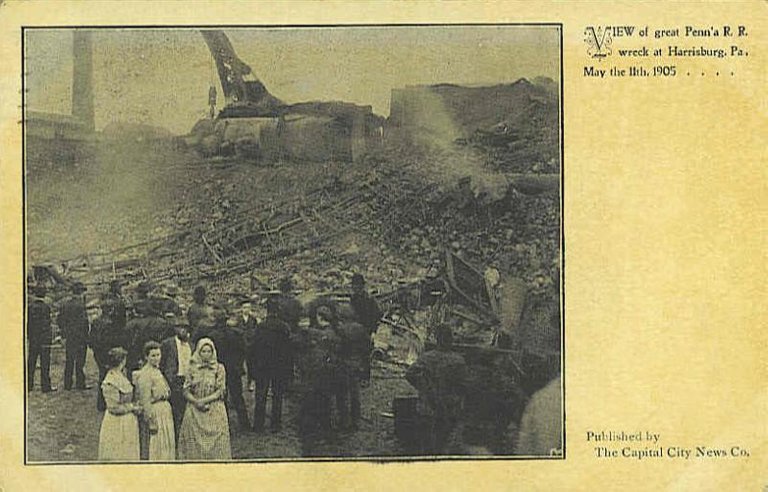

The Cleveland and Cincinnati Express Disaster of 1905

Train wrecks happen so infrequently in the US today that it's big news even if one derails without a catastrophic loss of life. For some commuters in the wee hours of May 11, 1905, things went from bad to worse in less time than it will take you to read the next paragraph.

Entering Harrisburg, Pennsylvania after passing through on it's way from New York the previous afternoon was the Cleveland and Cincinnati Express, hauling eight cars' worth of sleeping passengers. Unbeknownst to anyone aboard the Cleveland and Cincinnati, a freight train heading the opposite direction earlier had braked too hard to avoid a collision with a switch engine which was blocking its way.

The sudden brake derailed multiple cars beside an adjacent track: the very same track the Cleveland and Cincinnati Express now traveled. Under normal conditions, the railway would station a flagman a mile or so up the tracks to warn oncoming trains to slow down, but the Cleveland and Cincinnati Express was only minutes up the track when the mishap occurred. C&C Engineer H.K. Thomas saw the mess in front of him, but could not violate the laws of physics enough to stop in time. Having no other choice, he hit the brakes and crossed his fingers, hoping his engine (and all the trailing cars) might squeeze between the debris.

For a few seconds it seemed Thomas was in the clear: the engine and two cars behind it slid through unscathed. The third car, however, was a giant, roomy Pullman coach. Far too wide to fit through the gap, it sideswiped the other train and attempted to push its way through. This actually succeeded...at derailing everything.

That's actually the least worst part of this, if you can believe it. Passengers from the Cleveland and Cincinnati staggered from the wreckage to discover that, by some miracle, they'd all survived the crash. The worst mess came from all the burning coals and hot ash that burst out of the engine's firebox, but remarkably, no one suffered anything more than superficial injuries. While the crew got to work cleaning up and relaying the situation so no other trains came barreling along and added to the problem, the now very much awake passengers wondered how they were going to make their afternoon appointments and marveled at how close they'd all come to the brink of disaster. Then came the metaphorical 'Thanos Snap', courtesy of the fifty thousand pounds' worth of blasting powder carried by the previously-derailed freight train.

'Twenty-five fucking tons of explosives' and 'a bunch of burning coals and hot ash' make for an exponentially less jovial combination than 'beer' and 'pretzels'. The resultant explosion set every nearby wooden surface, including the rest of the passenger cars, on fire. It blew out the windows on every home and business for a mile up and down the tracks (did I mention this happened in Harrisburg, a rather populous area of the state?), and incinerated more than twenty people, including the engineer and two of his crew, on the spot. Over one hundred others suffered burns and injuries of varying degrees and intensities; noted theater producer and owner Sam Shubert, for whom the famous Shubert Theatre in New York is named, was among those killed. Compounding matters further, the shockwave from the blast caused a container of gasoline to fall off a shelf in a nearby cellar. It broke close enough to the active boiler that the open flames ignited the vapors; the resulting secondary explosion destroyed three more buildings and set several others on fire. All told, fire crews worked over seven hours containing the blazes both on the train tracks and in the nearby city itself.

You might think decorum prevailed and the reporters of the day treated the events in a way befitting the somber tragedies they were. This was 1905, after all, a time before the lawless wastes of the internet when men were men, women were women, and children were beaten within an inch of their lives if they spoke out of turn. A time we consider to be more staid. More proper. A time when people respected death instead of rushing to post pictures of it to their Instagram accounts so they could earn a million more followers.

You would be wrong.

Newspapers of the day gleefully recounted, in horrifying detail, the plights of the dead and injured in ways that would shame Jake and Logan Paul.

When all was said and done, the death toll stood at twenty-three, with the injured list more than quadruple that. Nation-wide attention (some 50,000 people are estimated to have visited the disaster site, not because they were helping, but because they wanted to gawk), and a butt-puckeringly enormous lawsuit on behalf of the families of the deceased, followed. The final absurdity: inspectors ascertained the initial train's derailment came as a result of a newly-installed air braking safety system. The air brakes didn't fail--they functioned exactly as they should have. Ironically, in doing so, the safety system averted a minor catastrophe only to cause an exponentially larger one resulting in over $200,000 in damages mere minutes later. Two hundred thousand bucks is a not-insignificant sum of cash, but remember, that's 1905 money. Adjusted for inflation, the damage estimate tops five million dollars.

Two days later, the US Senate put forth a bill suggesting rail companies not ship people and explosives on the same train--a common sense notion on par with "don't eat yellow snow", but one which apparently needed to be explained to rail companies anyway.

Fortunately everyone involved learned their lessons. Of course, in the 21st century, we'd never transport deadly, explosive, flammable substances by trains which--I'm sorry, what's that?

Oh.