Mass starvation and Cannibalism

November 1941

By early November some of the most vulnerable sections of the civilian population were beginning to die from starvation. On 2 November Stephan Kuznetsov wrote:

The temperature is really dropping now, and hunger is a constant presence amongst us. The food we are issued with is very poor. Today I saw some civilians crying by the roadside - they were so desperately hungry. They told me their babies are dying from malnutrition.

During late October and throughout November the Red Army was ordered by Zhukov and later by Zhdanov to launch numerous offensives from the Nevsky bridgehead in an attempt to break the German siege of the city. At this point the only route available for getting supplies into Leningrad was across the waters of Lake Ladoga. The German air force was bombing all Soviet ships which transported essential supplies across the lake. By early December the Red Army had suffered devastating losses in its attempts to break the German encirclement of the city largely due to the relentless massed fire from the German artillery. On 13 December Hitler’s chief of staff, Colonel General Franz Halder, wrote in his diary with great satisfaction:

The commander of the army group is inclined to the view-after the failure of all attempts by the enemy to break through our position along the Neva-that we may expect complete starvation of Leningrad.

By this point the fate of the population of Leningrad was sealed. It was condemned to mass starvation against the backdrop of one of the harshest winters in recent memory.

Besides starvation, an increasing number of young and old began to die from a variety of diseases from consumption to grippe. The relentless reductions in daily food rations led many to people to resort to a variety of extreme measures to supplement their starvation diet. Dogs and cats disappeared from the streets. Many tore the wallpaper from their the walls and scrapped off the paste which they believed was made from potato flour. People chewed and ate the wall paper as well to simply fill their stomachs. Lipsticks were eaten as food while face powder was mixed in with the diluted flour rations. As more and more inedible elements appeared in people’s diets from sawdust to plaster so did incidences of dystrophy and diarrhoea.

Harrison Salisbury has noted that:

A certain order of starvation emerged. It was not the old who went first. It was the young, especially those fourteen to eighteen, who lived on the smallest rations. Men died before women. Healthy strong people before invalids. This was the result of the inequity in the rations. … vigorous, growing children needed as much food as a worker. [Yet they only received half the bread ration of a worker] This was why they died so swiftly. The ration for men and women was the same … But men led more vigorous lives. They needed more food. Without it they died more rapidly than women.

Yelena Skryabina wrote in her diary, “Today it is simple to die. You just begin to lose interest, then you lie on the bed and you never again get up.”

It became increasingly common to see people collapse of hunger in the street.

After the war Nadezhda Ivanovna recalled how hunger-induced weakness led people to ignore the plight of those who had collapsed from hunger in the street. She recalled:

We all did things that made us ashamed. We had to in order to survive. We want to be saints we are not. There was one incident - I don't often talk about it - when I was walking home at dusk, exhausted. It was a time when people were afraid to be on the streets alone. I came to a crossroads. Two girls were in front of me. One of them collapsed in the snow and the other was trying to lift her up. ‘Help me, help me with my sister’, she pleaded as I approached. But I feared that if I bent down I would fall too and no one would come by who would help us up again. ‘I have a sister too,’ I whispered. ‘We are alone.’”

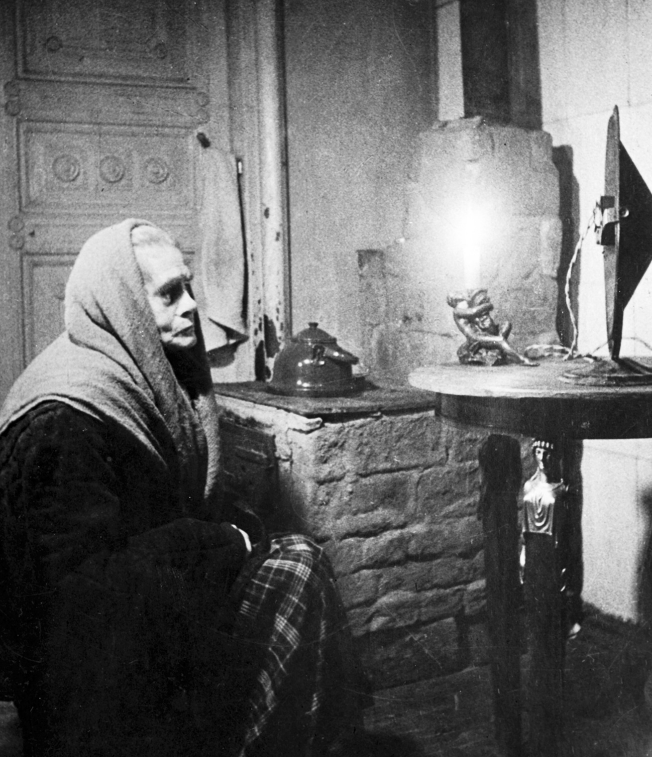

As each day started anew it required a Herculean effort of will for many to keep going about their daily business. Many realised how essential it was to keep up with the daily routines of ordinary life, as they knew that giving in and succumbing to hunger was tantamount to a death sentence for many people. In his diary of the blockade, which was published after the war. A.N. Boldyrev recorded his struggle for life:

Today I didn’t get up until 1 o’clock. Very weak. For the first time my face has swollen. Lying in bed my spirits fail, I experienced something like hysterics i.e. I simply howled for a while. … Death sucks one towards it like a current beneath a narrow bridge. As soon as you lower your guard you have to redouble your efforts to escape it.

By the end of November 18% of hospital cases were starvation related disease. Doctors became increasingly alarmed at the astronomical increase in dystrophy and scurvy. In some districts of the city the authorities struggled to keep up with the demand for death certificates. The month of November saw the deaths of at least 11,085 people from starvation.

Already rumours began to spread that some of the sausage meat which could be bought in the markets was not made of pork but of human flesh. Not surprisingly, the sex drive of most people evaporated. It became harder and harder to tell men from women. The birth rate dropped catastrophically during the winter of 1941/42. The birth rate was 25.1 per thousand in 1940 by 1942 this had collapsed to 6.2 per thousand.

The prices of food on the black market rapidly rose. A same loaf of black bread cost 60 roubles while kilo of meat went for 1,200 roubles.

Lake Lagoda

In the two months up to the freezing of Lake Ladoga on 15 November a meagre 24,097 tons of flour/grain was shipped across the water while 1,131 tons of meat and dairy produce were supplied to feed a population of over 2.5 million of whom over 400,000 were children. Besides food the other main cargo of these ships was munitions for the Red Army soldiers defending the city. Many of the small boats bringing in supplies sank due to a combination of being overloaded in stormy waters or were destroyed by German bombers and fighter planes who mounted regular patrols over the lake.

Thousands of refugees, mainly women and children, were killed as boats leaving the city from Osinovets to cross the lake to Novaya Ladoga were sank by German warplanes. One of the worst acts of murder by the German Luftwaffe came on 5 November 1941 when a boat whose decks were loaded with refugees was sank with the loss of 204 lives.

Once Lake Ladoga froze and was covered with thick ice the city authorities set up the so-called ‘Road of Life’ which involved convoys of trucks making the dangerous journey across the lake in the face of German artillery and aircraft trying to destroy the convoys and break up the ice. Truck drivers making the perilous journey would always leave the passenger door of their trucks open in case they had to jump out if the ice gave way.

Further disaster struck the city on 8 November when news came through of the German capture of Tikhvin, which severed the rail connection between Moscow and the Ladoga supply route. On that day Hitler spoke at a meeting in Munich where he declared with relish:

Leningrad’s hands are in the air. It falls sooner or later. No one can free it. No one can break the ring. Leningrad is doomed to die of famine.

Harrison Salisbury has noted that news of this calamity soon spread across the doomed city;

There were now panic and disarray in Leningrad. The news of Tikhvin’s capture spread like the fierce wind on the Nevsky from person to person.

On 9 November Dmitri Pavlov and his colleagues worked out that the city had flour for 7 days, cereals for 8 days, fats for 14 days, sugar for 22 days and no meat. On the other side of Lake Ladoga were 17 days of flour, 10 days of cereals and 9 days of meat.

Emergency orders were issued to try and keep the population alive. Rations for front line soldiers were cut from 800 grams a day plus stew to 600 grams a day and 125 grams of meat while units in the rear had their rations reduced to 400 grams of bread and 50 grams of meat. It was decided that there would be no reduction in rations for civilians as it was felt that to do so would ‘doom the whole city to more rapid starvation.’

Zhdanov and the Leningrad Defence Council gambled on the ice on Lake Ladoga becoming thick enough for trucks to travel over the ice. Factory workers had their bread ration cut to 300 grams (about two thirds of a pound) while for everyone else the daily bread ration was reduced to 150 grams. As by13 November the ice had not become thick enough to sustain the weight of trucks so, as a last resort, food rations for the population were reduced to starvation levels.

Pavlov knew that even these starvation levels could only be maintained for a few days. He waited and waited for the ice to freeze thick enough to sustain the weight of trucks. On 20 November food rations were cut again. Factory workers working in freezing cold conditions were now given 250 grams of bread while for everyone else it was reduced to 150 grams, which was two slices of bread per day.

The Approach of Mass Starvation

Harrison Salisbury in his account of the siege observes that,;

These rations doomed thousands to their deaths. By one estimate the cut doomed one-half of the population. Zhdanov knew this. So did Pavlov. They saw no alternative.

In desperation Zhdanov called a meeting of the leaders of Leningrad’s Young Communists. He told them that on these young people would rest the responsibility of trying to pull city though the unfolding famine:

Factories are beginning to close down. There is no electricity, no water, no food. The fall of Tikhvin has put us into a second ring of encirclement. The task of tasks is to organize the life of the workers - to give them inspiration, courage, firmness in the face of all the difficulties. This is your task.

Young communists were used to mobilise citizens to go out and collect ‘edible’ pine and fir bark. Each district of the city was given a target of producing two and half tons of sawdust each day to put into the bread ration.

To compound matters for the hungry population the drop in temperatures meant that many would freeze to death before they died of starvation. On 11 November it was minus 15 degrees and by 14 November it had fallen to minus 20 degrees.

During the last week of November rumours spread like wild fire that all rations would be halted at the end of the month. Mobs of starving people began to storm the few remaining food stores. On 25 November over 2,000 people barged their way into the Vasilevsky Island department store in search of food.

As each day passed many were killed in the huge queues for food by German artillery shelling which showed no mercy for the starving population. There was a concerted attempt by the German army to break the will of the population to resist. German artillery spotters watched the city, and when they spotted large gatherings of people sent the coordinates to their gunners would then launch a murderous bombardment designed to instil terror amongst the civilian population of Leningrad.

Vera Inber described the terrible fear she experienced caught out in the open mixed sustained burst of artillery fire. She had just boarded a tram on Bolshoi Prospect:

We had hardly started when the shelling began. Shells fell to the right and left of us. There was a roaring sound - the street was an inferno. Crashes reverberated as if we were at the bottom of a canyon. No one in the tram said a word. We were carried into the actual zone of fire. The most frightening part was to see people on the pavement running away from the very place we were approaching, getting nearer every moment…I can no longer remember how - but I managed to jump out, run across the street and into the baker shop on the corner. At the very moment I entered the shop a shell hit the tram. Everyone who had stayed in that tram was killed. Later, I learned that the shelling had been deliberately aimed at Sitnoy Market - into the midst of the crowd of people gathering there.

As winter approached the mental strain of the siege began to take a devastating toll on many people. The distribution of food was poorly organised leaving large numbers of people standing in line in sub zero temperatures while the German artillery pounded the city. In October the number of bread stores was reduced to 34, this meant that the remaining stores often ran out of bread before everyone had received their ration. This led many people to start queueing in line before 6am each day.

As the hunger of the population intensified it made walking the streets of Leningrad an increasingly dangerous occupation. Rumours spread of people being abducted and killed by cannibals. A growing number of people reported thefts of their ration cards and/or their bread ration itself while walking the streets. Nelly Pozner recalls an incident when she was out collecting the family bread ration with her mother:

One day I was at the bakers with my mother. We collected our ration - 125 g for each of us - when suddenly a youth rushed up, knocked into my mother snatched the bread from her hands. He ran off. Mum cried out in her loud operatic voice. A patrol soldiers was passing by. They ran after the boy, caught him and brought him back to the shop. The boy had already sunk his teeth into the bread. I have never forgotten that boy's face. It was swollen … and his eyes were expressionless, eyes that are no longer human. The soldiers asked my mother, ‘Was it him?’ ‘No’ she said, ‘it was not him.’ Thieves were shot on the spot. Perhaps it was too late for the boy and the bread would not have saved him.

As the siege intensified Leningrad's radio station began to send out broadcasts aimed at German troops who it knew were able to pick up its signal. An Austrian communist named Fritz Fuchs was put in charge of radio Leningrad's counter propaganda department. In his broadcasts he tried to strike a balance between a note of defiance coupled with an attempt to get German soldiers to consider what they were doing to the people of Leningrad. In one broadcast Fritz Fuchs stated:

German soldier - have you really thought about the meaning of this war, what you are inflicting on others, all the blood, all the suffering? You have marched triumphantly through half of Europe, and everywhere new cities have been waiting for you. You have always believed that you are the Master Race. This is not tiny Belgium vast Russia. You are now so close to Leningrad, German soldier, you are never going to see the city.

Sadly, it would appear from many accounts that most German soldiers had little or no sympathy for the people they were trying to starve. In mid November 1941 two German officers were captured outside the city and brought to the offices of Radio Leningrad for interrogation. Lieutenant Kurt Braun told his interrogators defiantly:

We know that everyone in Leningrad is dying of hunger. We have agents within the city, they have reported to us that cannibalism has started to occur. You will be destroyed. We have just captured Tikhvin, cutting your last supply route. Mass starvation within the city is now inevitable. You are all going to die.

As rations were cut once again in mid November and temperatures plummeted to minus 20 degrees, death from starvation became commonplace on the streets of Leningrad. Setting out in the morning to collect the daily bread ration became a perilous journey from which many did not return. Many simply collapsed and died on the street while some would simply stop and be unable to go on and would freeze to death. Lev Pevzner later recalled such a moment:

The November I was walking back from work, and at a certain place, by the Haymarket Square, I just felt that I could go no further. I came to a section of iron railing, surrounding a small garden, and I paused and leant against it. It was so very cold. But strangely I felt good standing there, really, really good.

A lady came up to me and said, ‘Are you okay?’ I replied, ‘Yes yes, I feel fine.’ But she persisted, asking, ‘Why don't you keep going?’ I just kept repeating, ‘I can't go on.’ Then she shook me, saying, ‘Get up please get up.’ She helped me get to my feet and accompanied me all the way back to my house making sure I got to the second floor waiting there until my mother let me in. That woman saved my life.

By late November the people of Leningrad faced a ‘truly catastrophic’ situation. Besides hunger and daily shelling from the German army. The trams stopped, the water supply to houses stopped as did the supply of electricity as the city's power stations ran out of coal and oil. The Leningrad government decided to start demolishing large wooden structures to provide firewood for the freezing population. Zhdanov gave the order for a large fairground on the fringes of the city to be chopped up.

Besides the perilous journey to collect the daily bread ration the people of Leningrad now had to add on a journey to collect water from the local rivers. When interviewed after the war Nelly Pozner recalled:

The water was cut off. We had to go to the river with buckets and boil the water before we could drink it. One day my mother came back in tears without the bucket. She told me she had been bending over an ice hole in the Fontanka when she saw a human head beneath the water. In her horror she let go. After that she had to use a kettle. It only held two litres and emptied so quickly that mamma would cry as she pulled on her felt boots again.

German artillery bombardments often started fires which more often than not were left to burn out of control. At the start of the war Leningrad had a shortage of firefighting equipment. This, together with the lack of running water, coupled with a weakened starving populace meant that fires were often left to burn themselves out.

December

The situation facing the population of Leningrad took a turn for the worse during December 1941 with the onset of mass starvation. During this terrible month children’s sleds began to appear across the city. On the sleds were the dying and the dead. In his diary for this period the artist Vladimir Konashevich recalls how he was traumatised by the sound of the squeaking of sleds carrying the coffins of children being dragged throughout the city.

Thousands of people were now dying each day. The numbers began to overwhelm the emaciated survivors who in any case simply did not have the strength to take the bodies for burial. At the Hermitage Museum when a member of staff died their body was carried to the Vladimir corridor in the hope that an army crew would come along to take the bodies away.

Many Leningrad diarists commented on the quiet of the city. The city became as quiet the grave. The silent streets saw increasing numbers of very frail people who were starving slowly pulling children’s sleds. One diarist Luknitsky wrote:

To take someone who has died to the cemetery is an affair so laborious that it exhausts the last vestiges of strength in the survivors, and the living, fulfilling their duty to the dead, are brought to the brink of death themselves.

On some sleds there were small coffins, however in many cases children's bodies were simply covered in a sheet. At the cemeteries there was no one to dig a grave, or to say a prayer the bodies were simply dumped on the frozen ground.

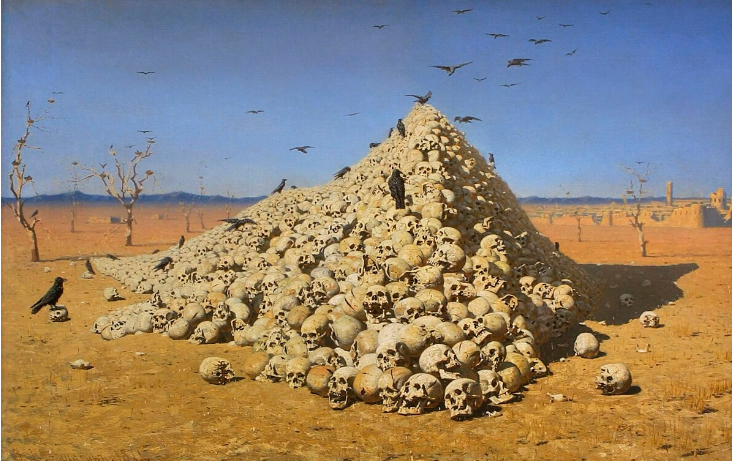

Corpses began to pile up in huge numbers on the grounds of hospitals. Reception rooms at hospitals began to resemble catacombs as they were full to overflowing with dead bodies. On many occasions family members died from the effort of taking a body of a loved one to the reception room of the hospital. Deaths were no longer registered under these harsh conditions. Starving staff simply recorded the numbers of bodies for the city authorities.

Leningrad was experiencing its coldest winter in modern times with an average temperature in December of 13 degrees below zero. The weakened population lacked the strength to hack out graves. The city authorities sent army sappers to numerous cemeteries and were ordered to use dynamite to blast large trenches which would be used as common graves for the population. During the winter of 1941-42 662 common graves were dug the total length of which was 20,000 yards.

Y.I. Krasnovitsky, director of the Vulcan factory, recalls his horror on first witnessing a mass burial:

I remember the picture exactly. It was freezing cold. The bodies were frozen. They were hoisted onto trucks. They even gave a metallic ring. When I first went to the cemetery, every hair stood up on my head to see the mountain of corpses and the people, themselves hardly alive, throwing the bodies into trenches with expressionless faces.

Despite the efforts of the authorities, large numbers of bodies remained unburied across the city. In desperation the city government issued draconian decrees threatening with execution those that simply abandoned corpses by the roadside. One diarist recorded his impressions of driving towards the outskirts of the city:

The nearer to the entrance to Piskarevsky I approached, the more bodies appeared on both sides of the road. Coming out of town where there were one story houses, I saw gardens and orchards and then an extraordinary formless heap. There were on both sides of the road such enormous piles of bodies that two cars could not pass. A car could only go on one side and was unable to turn around. Through this narrow passage amidst the corpses, lying in the greatest disorder, we made our way to the cemetery.

During this mass starvation the smell of the city began to change. The streets began to smell of turpentine. Trucks taking corpses to the cemeteries were drenched in turpentine. Harrison Salisbury has observed, “The harsh smell lingered in the frosty air like the very scent of death.”

The streets of Leningrad became terrifying places as chaos and disorder began to prevail. Elena Kochina wrote the following blood-chilling description of the corrosive effects of the siege on people struggling to survive:

Some seek to save their lives at any price: they steal ration cards, they tear bread out of the hands of passers-by, eating it under a hail of blows, they even kidnap children. They roam the streets, mad from hunger, and the fear of death. Countless tragedies are taking place every day, dissolving into the silence of the city…Meanwhile, the Germans look at Leningrad with cold curiosity.

The German besieging army was fully aware of the mass starvation gripping the city. Its spies gave daily reports on the tragedy unfolding. A situation report in December 1941 gives a chilling insight into the impact of mass starvation:

The people of Leningrad have become so habituated to our artillery bombardment that hardly anyone goes to the shelters anymore, and casualties have therefore greatly increased. The number of deaths from starvation is now rising dramatically. For instance, on 17 December, an informer on Stachek Street, between the Narva Gate and the city limits, saw six people collapse from hunger, lying where they fell, unable to move, over a distance of five kilometres. These cases are now so frequent people no longer go to the assistance of others. Because of the general exhaustion of the civilian population, very few are able to provide effective help.

As the month of December progressed mass starvation had a radical effect on people’s behaviour. In some it brought out the worse as they resorted to any means necessary to secure food while many others stood firm and maintained their humanity only taking what was due them and /or helping others when they themselves were not far from death’s door.

After the war Tatiana Chertkova was interviewed about her experiences of surviving the siege:

It was the values that my parents instilled in me that enabled me to live through the siege. At home we divided our bread between us. We could never consciously take anything if it involved hurting someone else.

Her friend Lidiya Ivanovna agreed with that sentiment:

That’s right. Sometimes at the bakers emaciated old people held out pieces of bread to us children, but we never took anything that didn’t belong to us. It was only a short step over that line but we never crossed it. I remember one day I came across a building that had just been bombed. On Chernyshevsky. It didn’t have a proper concrete shelter, just an ordinary basement. The house had collapsed, burying those inside. A soldiers stood by the ruin, covering his face with his hands. ‘They’re all dead!’ he wept. Then he noticed me. ‘Here, girl take this bread.’ He then offered me three loaves, two white and one brown. ‘What if someone comes out alive,’ I asked. ‘What will they eat?’ He just shrugged and shook his head in despair. I only took one loaf.

Zoya Taratynova was a frail fourteen year old girl who saw how starving people reacted in different ways to hunger. One day on her way home she saw a large crowd of people hacking an old horse to pieces as it lay on the ground too weak to stand any more. Then several days later she was delivering a cart full of bread from the bakery to a hospital. She soon found company in the form of a sizeable crowd, full of haggard and desperate looking people. The cart got stuck in a rut in the road and some loaves fell on the floor. Zoya was terrified and fearful for her own life and for the cart of bread. Instead of running away and abandoning the bread she displayed great courage and pleaded with the crowd:

‘Please don’t take the bread - it’s for the hospital.’ The crowd hesitated for a moment. Then thankfully the crowd stepped forward to pick up the loaves from the floor and helped get the cart out of the rut in the road. She later recalled, They could smell the bread and even touch it - but not a piece was taken.

The growing horror of daily life imposed an immense strain on everyone. Olga Mikhailova who worked at the Hermitage remembers:

The blockade began to reveal things more clearly. You could see straight away the good and bad sides of a person. Those who were greedy certainly grew worse, and tried to live at the expense of others. But goodness would flourish too.

Michael Jones has observed of this period of the siege:

The mood of the city’s population lay on a knife edge. On one side were the finest human qualities, stoic cooperation and heroic endurance. On the other lay the basest, cruellest indifference and the predator’s instinct for survival regardless of cost to others.

One of the most agonising dilemmas people faced was should they help someone who had fallen down on the street. Valentina Grekova recalls an incident when she was nine and going home with her mother:

My mother was carrying me past the Admiralty Building on a sledge. We were both feeble with hunger. But suddenly we saw a little boy clinging to a rail. He was collapsing with exhaustion, unable to go any further. I remember my mother saying: ‘We have to help that boy!’ Neither of us had much strength left. But my mother moved me from the sledge and put the little boy on it. Then we found out his address, and slowly made our way to his home. When we got there, a woman ran out, calling his name in relief and delight. It was Boris Pushkin - and it turned out that he was a descendant of the great poet Alexander Pushkin. For us that seemed a good omen - by rescuing the little boy, we had made the right moral choice.

However, making the right moral choice was no easy thing when you were very weak from starvation and fearful that if you helped someone it might lead to your own death as well. Tatyana Antonovna remembers her own mother’s moment of truth when walking home from her factory job:

She was walking through the snow, and bodies were lying, scattered about, everywhere. But one man was still alive. He cried out: ‘Dear lady! Give me your hand, I am freezing to death here.’ She bent over him and said, ‘Forgive me. I have a daughter at home. I am very weak, and can hardly walk myself. I haven’t the strength to help you - you will pull me over and I’ll fall. Forgive me.’ She turned away and walked on. She did not help him. When she arrived home she told me about it, and broke down and cried. ‘I have committed a sin,’ she kept saying. ‘But what could I have done? I would have been lying there myself.’

As the city stared into the abyss the population were dealt another severe blow to morale with the news that a number of Leningrad’s city leaders were evacuated by plane on 8 December. This contributed to a sense of being abandoned which was felt so strongly by many. It sent a clear message to the people that there was going to no be relief from the German siege and that the people were very much on their own.

Against this backdrop of feeling abandoned people began to self organise in small groups. These small collectives were made up of family, friends and/or work colleagues. They enabled people to pool their meagre resources together in order to survive and above all else to keep their humanity intact.

Anatoly Molchanov recalls this self organisation sprang from a realisation that:

We realised that we had a better chance of survival if we formed into groups.” He further noted the spontaneous nature of this phenomenon; “We were not instructed to do this by anyone; we made the decision ourselves, quite spontaneously. We gathered together in a spirit of mutual support. We called ourselves ‘friendly collectives.’

This spirit of cooperation ensured that no one was left on their own and everyone benefited from an egalitarian notion of from each according to his ability to each the rations would be divided equally. Alexandra Shushtakov remembers:

In our communal apartment we had fifteen people living with us. And we always shared what we had. If someone got hold of carpenters glue, we made a jelly for everyone; if someone went outside the city and found some frozen scraps of food, we would boil them. One of us got a piece of horse hide. We burnt off the hair and made a soup out of it- a delicacy. The crucial thing was, we were doing it all together.

Molchanov states that these groups were not just founded on the idea of merely surviving but also on the idea of keeping hold of one’s humanity. He observed that:

People who isolated themselves from others went down. And we saw many people in the city becoming scoundrels, always seeking to profit from the misfortunes of others. But something else was coming to life as well - a deeply felt wish to help each other in adversity.

The onset of the new year saw an intensification of the mass starvation which held the city in its iron grip. One diarist, Georgi Knyazev wrote, “People are living on their last hope...the weakened just keep on dying.”

##January

On 8 January 1942 Alexander Boldyrev recorded in his diary the following observation:

The death rate is astronomical … I saw with my own eyes a caravan of sledges, loaded with coffins, boxes or simply corpses in sacks, making it way to the cemetery. There I saw corpses left just as they were, dumped at the entrance, turning black in the snow. For some reason, one of them sat, his legs spread wide, on a large box, wrapped in a multi-coloured floor cloth … Are we nearing the end? We are a city of the dead, shrouded in snow.

Reports from the NKVD confirmed the dire situation facing the city and noted the breakdown of law and order regarding food distribution. On 12 January one report noted:

Over the last three days there have been instances in which citizens queuing for food have demanded servers give them bread several days in advance. On a number of occasions they have met any refusal with force, seizing and distributing the bread to others. The number of thefts and murders where food was the motive has risen.

On 15 January the diarist Nikolai Gorshov described the following scene, “On a street corner, some people began to gather - mostly teenagers - when it was evening and already dark. They waited until a bread wagon approached, then attacked it, and stole it’s cases of loaves.”

The same report made the self evident observation that “The mortality rate continues to rise.” In the first ten days of January 1942 official figures recorded 28,043 from starvation. This figure was undoubtedly a huge under estimate of the massive numbers of deaths from famine. Many deaths were not being registered as there were far too many against the background of a collapsing administrative system.

The NKVD report of 12 January included the observations of informers who relayed numerous critical comments on the terrible situation facing the city. One comment lamented:

The situation is hopeless. It is impossible to live on 200 grams of bread. So many people are dying of hunger. All cats and dogs have been eaten and now they are starting on people. Human meat is being sold in the markets, while in the cemeteries bodies pile up like carcasses without coffins.

The Leningrad authorities began to publicly step up its propaganda blaming racketeers and food thieves for the food distribution crisis. The reality was that it was the failure of the authorities to distribute food effectively which greatly accelerated the spiralling mortality rate. Evgeny Moniushko’s brother was a party organiser in the city and he told him:

During the first half of January, for reasons unrelated to the lack of flour, but instead due to the reduced amount of fuel for baking and the interruption of the water supply, bread deliveries to stores were seriously disrupted. As a result, there were severe bread shortages. Long lines of people stood in the freezing cold, refusing to disperse, even after enemy shells had exploded nearby.

This delay had a catastrophic effect on many people who were starving and suffering from severe stress. Moniushko’s brother told him, “This delay proved too much for some people to endure, and, as a consequence, the number of starvation victims began to increase noticeably during this period.”

On 23 January 1942 the last water pumping station in the city stopped working. Large groups of people went down to the Neva river and broke holes in the ice. To avoid the danger of falling down the river embankment, people formed a human chain passing buckets of water from hand to hand ensuring that precious water got home.

On 24 January the city authorities raised the bread ration as a desperate measure to forestall a planned hunger demonstration. They now began to fear the starving population. Michael Jones has commented on the cynical nature of this action when they knew that the city was about to run out of bread in a matter of days:

It was all a cynical diversion. Food distribution problems were worsening dramatically. Even as they made the announcement, Leningrad’s leaders knew that in matter of days bread would be no longer reaching the stores. When that happened, people would be left with absolutely nothing. The most terrible period of the siege was about to begin.

February

Leningrad stared into the abyss as society began to break down

In February 1942 the German Eighteenth Army issued a new report on the catastrophic situation facing people of Leningrad. Thanks to its informers, which operated throughout the city, German commanders had an accurate picture regarding the mass starvation which was taking place thanks to the siege they maintained.

German operational situation report February 1942:

By December large part of the population showed hunger swellings. Increasing numbers of people collapsing on the streets and dying. During the course of January the population was dying en masse. In the evening hours corpses were pulled on hand sledges from houses to cemeteries, where they were simply thrown onto the snow due to the impossibility of digging. Lately relatives are saving themselves the effort of going to the cemetery unloading corpses at the curbside.

The Nazis asked their informers to make counts of the numbers of bodies across the city so as to give them as accurate a picture as possible of the impact of their genocidal siege:

In one afternoon at the end of January a defector undertook to count passing sledges loaded with corpses on a main street of Leningrad. A hundred were counted within an hour. In many cases, the corpses were piled up in yards and unfenced squares. A pile of corpses in the yard of a bombed apartment block was 2 metres high and 20 metres long. In many cases however, the bodies are not even taken of apartments but only placed in unheated rooms. In air raid shelters one often finds dead bodies that have not been removed. Also, for example, in the Alexandrovskaya hospital there are about 1200 corpses placed in unheated rooms corridor, and the yard.

At the end of January it is rumoured that 15,000 were dying each day and that 200,000 died in the preceding three months. This number is not too high in relation to the total population. It must be taken into account, however, that the number of dead will increase greatly with every week the present conditions of hunger and cold continue. The food rations stored and distributed to individuals will have no effect. In particular, children are said to be becoming victims of the hunger, namely infants for whom there isn’t food. Recently, a smallpox epidemic is set to have broken out, which is also claiming many children's lives.

As the famine intensified the people of the city began to experience a terrible increase in food related crimes. The breakdown in law and order was a terrifying ordeal for the starving population.

During the next two months the people of Leningrad were pushed to the very brink. On 24 January 1942, the bakeries stopped working due to a lack of water. The food supply became completely disrupted with massive queues forming outside the bread stores. On 26 January Elena Skrjbina wrote in her diary, “There is no bread – none of the bakeries have baked their quotas.” When no bread appeared in the bakeries the next day mass panics broke out across the city. Alexander Boldyrev wrote on that day: “I have to fight for my life now, for my very existence. There is nothing in the stores...I have to find water – but where? The River Fontanka is polluted. Perhaps we are entering our final days?”

At this point it appeared to many that the city was entering it’s final death agonies. On 28 January, fires broke out in several parts of the city. Nikolai Gorshkov gave a grim portrait of the situation on that day:

“The temperature is minus 27 degrees Celsius…The shelling has caused fires in the city…Many of the high rise buildings are in flames. The fire brigade no longer has the resources to put the fires out – there is simply not enough water. The situation is most ominous, for parts of our city are in flames and the fires are completely out of control, casting an eerie, frightful light. People are talking about a growing number of incidents, where, under the cover of darkness, gangs attack anyone seen carrying food. They are also speaking of a rise in cannibalism, and it is truly hard to record this.”

From late January to early February many people went an entire week without food. Not surprisingly, people were now dying like flies. Igor Chaiko wrote in his diary, “Corpses, corpses, corpses, left in the snow hills, along the city streets and lanes, wrapped in blankets, curtains and shifts.” Tamara Zaitseva later recalled of this period: “We could see people’s bones through their skin, as they searched the city, scavenging for scraps of food. At home, we started eating our books – mother soaked the pages in water, and we swallowed the liquid.” Tamara recalls that the little girl she used to play with across the street had disappeared. The little girls mother and grandmother, driven insane by hunger had eaten her.

The historian Michael Jones has observed of this period;

The madness of unspeakable hunger was sweeping the city, and alongside it something more calculated and cold blooded...Organised bands of cannibals were now working within Leningrad.

Cannibalism

He points out that during February the Leningrad authorities were in danger of completely losing control. Back in November 1941 rumours spread about meat patties at the local markets being contaminated with human flesh. Many parents began to make sure their children never left the house due to these rumours.

Cannibalism came an ever present danger. In the first ten days of December 1941 there had been only nine arrests for cannibalism. However in the first ten days of February there had been 311 arrests made for the crime of cannibalism. Elena Martilla remembers, “It had become dangerous to make a journey through the city, and it was becoming difficult to trust others.”

Nikolai Gorshkov made a visit to a local police station he recalls that twelve women were being held there all on charges of cannibalism:

One woman, utterly worn out and desperate, said that when her husband fainted through exhaustion and lack of food, she hacked off part of his leg to make a soup to feed herself and her children. Another said that she cut off part of a dead body lying in the street – but was followed and caught. These women are crying: they know they will soon be executed.

Gangs of organised cannibals infiltrated various public services. For example, a group of doctors were hacking pieces off dead bodies brought to one of the hospitals. A gang of twenty cannibals were caught after killing military couriers coming into the city. More and more rumours spread of cannibals using various ruses to lure people into their lairs.

One of the centres for the cannibal underworld was the Haymarket. Anatoly Darov later told the story of how two of his friends had visited the Haymarket in order to trade six hundred grams of bread for a pair of winter boots. They started talking to a well dressed healthy looking man and haggled over a price for the boots. The well dressed man told them that his boots were at his flat in a nearby side street. He took them to a large building which had not been damaged by German bombing. Once inside he told the young couple to climb up a staircase to the top floor flat. At the top floor the well dressed man knocked on the door which when it was opened released a disturbing, warm, heavy smell. Through the opening in the door the young couple glimpsed several human body parts swinging from hooks on the ceiling. At this point the two cannibals lunged towards the young couple. Terrified the young couple fled down the staircase ahead of their pursuers. They ran out into the street and bumped into an army patrol passing through the lane. The couple screamed “cannibals!” Soldiers from the patrol rushed into the building and several moments later shots rang out. A few minutes later, the soldiers reappeared carrying a loaf of bread which they had taken from the great coat of one of the dead cannibals which they then gave to the young couple. The soldiers told them that they had found five human bodies hanging in the cannibal’s flat.

People became afraid of going out into the street to collect their food rations or take the body of a loved one to the nearest cemetery or hospital. Eight year old Nina Pechanova watched her entire family die from starvation. After her mother died at the beginning of February 1942 she was completely alone. After the war she remembered, “For three days I clung to my mother’s corpse, I was terrified of leaving the apartment - I was so scared of cannibals.” When she did summon the courage to leave the apartment and go and collect some bread she was stopped by two adults in the street. They said to her, “Give us your bread little girl, or we will eat you.” Nina dropped the bread and fled in terror to her home. The next day, delirious with hunger, she once again summoned up the courage to leave her home and go and collect her bread ration. She later recalls, “I decided that I was going to fight for my life.”

Many people reported a family member gone missing. When they reported this to their local NKVD office they would be told to look through boxes of clothes which were arranged district by district. If they found any clothes belonging to their loved one then at least they would know in which district they were killed by cannibals. The NKVD openly admitted to members of the public that the Petrograd side of the city was overrun with cannibals.

Besides, cannibalism there was a huge wave of food related thefts which ranged from stealing a person’s bread ration to stealing ration cards. The loss of a ration card was tantamount to a death sentence at this time of the siege. Bakeries were often broken into as were shops which distributed food rations.

To counter this food related crime wave the Leningrad authorities sent special patrols of Red Army soldiers across the different districts of the city. They had orders to shoot looters, cannibals or food thieves on the spot. Colonel B. Bychkov kept a diary of the problems he encountered when out on patrol. He describes how his men would stop suspicious looking people and search them for stolen ration cards or unaccountable food supplies. If found the person or persons would be shot on the spot.

Despite the death and destruction which was overwhelming the city many Leningraders found solace in books. Those who had not burn their books for fuel found Tolstoy’s War And Peace to be a great comfort. Lidiya Ginzburg remembered:

Whoever had enough energy to read used to read War And Peace in Leningrad. Tolstoy had said the last word about courage, about people doing their bit in a people’s war. And no one doubted the adequacy of Tolstoy’s response to life. The reader would say to himself: ‘Right-now I’ve got the proper feeling about this. So then, this is how it should be.’

For some, at least, in February 1942 salvation came with their evacuation across the ice road which had been constructed in atrocious conditions over the surface of Lake Ladogoa. Those who were not connected to the privileged elite amongst the city authorities were evacuated in open trucks. To get evacuated by open air truck people had to pay for their fare with bread. No food or shelter was provided for people making the perilous journey across Lake Ladoga. As Michael Jones has observed in his account of the siege the transport convoys across the ‘Road Of Life’ were plagued by corruption.

Many died on the journey across the ice road just when it seemed they were to be saved from famine. Olga Melnikova, a medical workers on the ice road, recalled,;

We would see sick, emaciated mothers, wrapped in blankets, clinging to their babies and small children. These people looked horrific. Their children were so tiny, so wizened-we called them the ‘aged little people.’

When, unable to get on an open truck, some people in desperation decided to try and walk across the lake. This was not permitted and many were arrested by the NKVD when they reached Lake Ladoga. Those who evaded the patrols often died when they picked up German mines, dropped by the Luftwaffe, which were disguised as food cans.

Many Leningraders were appalled by the corruption and mismanagement of the authorities when it came to the so called ‘Road Of Life’. Dmitry Likhachev bitterly recalled, “It was never the ‘Road Of Life’- the sugary term used by later writers. It was always known as the ‘Road Of Death.’”

Truck drivers evacuating the poor of Leningrad drove as fast as they could across the ice road. If the truck hit a bump in the ice many mothers lost hold of their children who flew out of their arms onto the ice where they were often killed on impact. The drivers never stopped despite the agonised pleas of the mothers. Sometimes mothers were separated from their children only to see the truck carrying their children crash through the ice. The drivers never stopped to let the mothers try and rescue their drowning children. Besides this, the evacuees had to endure German shelling of the ice road and snowstorms. Michael Jones has observed;

So much more should have been done to help. Instead, robbery and corruption were rife. The weak had their possessions stolen and were pushed under the ice.

By the end of January 1942 over 2,000 tons of food had been brought across Lake Ladoga yet it was hoarded by the Leningrad Party elite fuelling the famine of the population. At the end of February 1942 the German army issued a report on the catastrophic situation in Leningrad:

The ice road across Lake Ladoga is now being used to evacuate some of Leningrad’s inhabitants. The number of evacuees is insignificant compared to those dying within the city. The drastic reduction in Leningrad’s population continues unabated. Estimates of the daily death rate vary, but are always in excess of 8,000 and often significantly more. Causes of death are hunger, exhaustion, heart failure and intestinal disease.

The growing break down in law and order forced the Leningrad authorities to issue more food to the shops. On 18 February Vasily Vladimirov noted in his diary: “Sausage has appeared in a few of the shops. There is a rumour that more meat will become available.”

Many previously loyal Party members became enraged at the corruption and callous indifference of the Communist Party elite in the city. The NKVD often produced reports based on comments reported by its informers. On 23 February a report carried the comments made by the head of one of the city’s factories:

The authorities announced that we had substantial reserves of food – but in practice they could not even lay in stores of dried roach, which we used to stoke up the ovens. I have been in the party a long time, and used to carry out its directives in good faith, but now I realise that I have been lying to the people.

Others were even more blunt. The writer Ivan Gruzdev wrote;

Leningrad’s leaders are appallingly incompetent. They are responsible for a massive number of deaths from starvation. Ordinary people loathe Popkov [mayor of the city], and many women in the streets say they would like to shot him dead personally.

The artist Anna Ostroumova wrote about the corruption in the food distribution system which was responsible for so much death and suffering:

In bakeries and co-operatives they cheat the unfortunate inhabitants; in soup kitchens and children’s centres they simply steal. The same thing goes on, I think, at the highest level of food distribution. What happened to the 200 cars of food, brought as a gift to Leningrad from the collective farm workers? On many occasions we have received gifts of food from various districts [within the USSR] – but what do we actually see of it all? Everything gets lost in the ‘apparatus.’

Despite the horrors of the siege many ordinary citizens of the city discovered an incredible resilience which kept themselves alive and enabled them to help others who were on the verge of death. Mikhail Chernorutsky, a doctor who treated many for clinical dystrophy, an illness caused by severe malnutrition observed:

We saw quite a few cases in which, all other conditions being equal, a weakening of the will to live, depression and giving up on one’s daily routine considerably hastened the course of the disease and led to a sharp deterioration in the general state of the patient. Conversely, firm and purposeful self-belief, cheerfulness, optimism and an organisation pattern of life and work – even if such an outlook seemed entirely contrary to actual events – sustained the weak body and apparently gave it new strength.

Thousands of young communists led the way and organised themselves into service brigades which visited people at home to provide medical aid and supply food to starving citizens. If possible they also removed the dead. They also rescued many starving children found clinging to their dead parents. Harrison Salisbury has observed, “The sights which met the eyes of the youth brigades in the frozen and bleak flats of Leningrad were almost beyond the power of a Durer or a Hogarth to depict.”

The young communists also carried water from the River Narva to bakeries and took people dying of starvation on sleds to local hospitals. The official report of the Young Communists notes that its brigades took food to 10,350 people on a daily basis.

Many others heroically rose to the challenge posed during the gravest time of the siege. In freezing temperatures, which on occasions fell to minus 40 degrees, thousands of people put their own lives on the line to serve on the ‘Road of Life’ across Lake Ladoga bringing essential supplies into the starving city. Thousands of starving young people worked in the freezing factories to produce bullets and artillery shells. By February 1942 the factories had stopped working as there was no electricity and no heat for the plants to work. In this situation the strongest amongst them formed small groups which visited people in nearby flats to bring a small amount of food or water or even remove the dead.

Dmitri V. Pavlov, who was in charge of Leningrad’s food supply, has estimated that during January-February 1942 around 199,000 people had died from starvation. Many historians state that this is an underestimate due to the collapse of the medical system during this period when large numbers of deaths were not recorded. Most people would keep on using the ration cards of a family member who had died giving the authorities an inaccurate view of how many people they were actually feeding.

Besides death from starvation, it should be noted that the death rate from all diseases rose astronomically during this period. Harrison Salisbury gives the following figures: death from typhus rose from 4 per cent in 1941 to 60 per cent in 1942, death from dysentery rose from 10 to 50 percent, stomach diseases rose from 4.5 to 54.3 percent. The number of people suffering from chronic diseases rose dramatically. For example, over 40 per cent of people aged over 40 years of age were estimated to be suffering from heart disease.

Despite the intensification of the famine during the first quarter of 1942 the situation facing the city did improve in several crucial areas. For example in late January 1942 the mass evacuation of people began across the ice road on Lake Ladoga. As noted earlier, many thousands died during the perilous journey. Despite this, it is estimated that from 22 January to 15 April over 554,000 people were evacuated from the city including 35,713 wounded Red Army soldiers.

Thousands of Leningraders were dying every day from starvation yet the people clung on determined to thwart the German army which was working so diligently for their demise. The poet Olga Berggolts, whose radio broadcasts inspired so many to keep alive, told her audience:

That winter, death looked straight into our eyes, and stared long, without faltering. It wanted to hypnotise us, like a boa constricter hypnotises its intended victim, stripping him of his will and subjugating him. But those who sent us so much death miscalculated. They underestimated our voracious hunger for life.

Pavel Luknitsky exemplified this determination to save the people of the city when he wrote in his diary;

I am happy that I did not run away, that I share its fate, that I am a participant and a witness of all its misfortunes in these difficult, unprecedented months. And If I live, I will remember them - I will never forget my beloved Leningrad in the winter of 1941-42.