The Siege Begins

On 28 September 1941 Field Marshal Leeb received an order from Berlin which stated German troops would not accept the capitulation of the city under any circumstances.

To prevent the German capture of Leningrad, the cradle of the October Revolution, Stalin was forced to take drastic action. On 11 September he dispatched General Zhukov to replace the incompetent Voroshilov with orders to hold the city at all costs. Zhukov’s first action was to countermand the suicidal order to scuttle the Baltic fleet. He realised that the big guns on these naval ships could provide much needed firepower for the defence of the city.

Previously, Voroshilov had bungled the evacuation of the Baltic fleet as it escaped from Tallinn leaving it in port until ordered to evacuate by Stalin. As the fleet, together with transport ships carrying civilians fled to Leningrad, the Luftwaffe bombed it mercilessly. No air cover was provided to protect the fleet. Several transport ships crowded with civilians were sunk including the Virona where the passengers sang the Internationale as it went down.

After the war Zhukov in his memoirs recalled the pivotal moment in the defence of Leningrad:

I knew the city and its environs well because I had studied there some years before at a school for cavalry commanders. Much had changed since then, but I still had a good idea of the battle zone … Energetic and resolute action was called for. The strictest order and discipline had to be maintained. Troop control needed to be tightened. We were working to stabilise conditions in the blockaded city in a most complicated situation.

His first priority was to stabilise the defence line around the city. The battered Eighth Army was cut off in a narrow strip of land around Oranienbaum. Meanwhile, the Forty Second Army and Forty Fifth Army were both retreating in disarray. Besides this, he gave orders to build up the city’s meagre defences which were in not fit state to hold off a frontal German assault on Leningrad.

Zhukov divided the city into six defensive sectors. Trenches were dug in each sector and strong points were built and anti-tank gun emplacements were created to be manned by new recruits drawn from reserve battalions. A crucial part of the city’s defence were to be the 338 big guns of the Baltic fleet. He believed that concentrated firepower would be effective in keeping German forces out of the city. In the week following one of the naval batteries of the Baltic fleet destroyed 35 German tanks, 12 artillery installations, an ammunition train and battalion of infantry.

On 16 September Zhukov issued military order number 419 which made a series of blistering criticisms of the hopeless Voroshilov. Action was now taken to coordinate action between the Baltic fleet and the Red airforce, reconnaissance planes were now accompanied by fighter escorts.

Zhukov took drastic action to prevent any further retreat by Red Army units. He issued an order to shoot any soldiers who withdrew from the new defence line. In some ways this action was uncalled for as the Germans had already taken the decision to consolidate their front lines and lay siege to the city. Hence the decision by Hitler to despatch the Panzer divisions attached to Army Group North to Operation Typhoon which was the attack on Moscow.

Sadly, Zhukov let arrogance and pride get the better of him and he ignored the mounting evidence that the Wehrmacht was digging in for a lengthy siege. From 18 to 21 September his head of intelligence reported on the movement of German armour away from the city. Zhukov angrily dismissed such reports out of hand. On 24 September he received another report that the Germans were forcing local people to chop down trees and help German troops build winter dug-outs and permanent trenches. Zhukov’s response to this report was characteristically blunt, “All my orders about active defence and local attacks remain in force.”

He had done great work to reorganise the city’s defences and stabilise the front around Leningrad. Tragically, Zhukov who promised Stalin that he would save Leningrad from capture, now sent his exhausted troops into a series of wasteful and futile attacks against the Wehrmacht. Woefully under strength and lacking both weapons and ammunition these costly attacks achieved nothing beyond getting thousands of soldiers killed. Despite some of his commanders openly opposing these attacks Zhukov remained adamant that they would continue.

Mikhail Nesihstadt, a radio operator at Leningrad’s Smolny Institute where the city authorities were based said of Zhukov:

He was a big theoretician and strategist – but he never seemed to care about human losses. He continued to order offensive after offensive against the enemy, regardless of the cost in lives. On a number of occasions local commanders were pleading with him that they were barely clinging on, and they desperately needed more troops and ammunition and that to try and launch an assault was madness. But Zhukov would not listen. I can still remember his chilling response: he would simply repeat ‘I said attack!’

The most ruinous of these attacks, which would be continued by his successors, was the decision to launch a series of attacks on German positions from a tiny foothold on the eastern bank of the Narva river known as the Nevsky bridgehead. Red Army soldiers in large numbers were crammed into this very exposed bridgehead. They had an adage to express their feelings towards this killing ground which claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of Red Army men, “If you have not seen the Nevsky bridgehead, you have not seen the real face of war.”

Michael Jones has commented that once the Germans had dug in and reinforced their position around this very exposed Soviet bridgehead and brought up their heavy artillery then the Nevsky bridgehead became a “death trap.’’ The Red Army soldiers stationed here had little artillery support, no air cover and were being “systematically blasted to pieces.”

Zhukov, aware of the futility of maintaining this bridgehead, which was suffering horrendous casualties, kept pouring troops into this killing zone which was a fire bag for the German artillery. One can only surmise that having promised Stalin that he would take measures to actively defend Leningrad he felt unable to back down from this military disaster out of fear of losing face.

On 5 October Stalin rang Zhukov to enquire about the situation facing Leningrad. The General acknowledged that German attacks on the city had stopped putting this down to his policy of ordering futile assaults on dug in German positions. This was a downright lie and ignored the fact that German troops had been digging in during the last two weeks of September. Satisfied that the situation around Leningrad had stabilised Stalin now recalled Zhukov back to Moscow to deal with yet another crisis - the German assault on Moscow.

Unfortunately for the citizens of Leningrad, the ineffectual Zhdanov was put in overall command of the city. Jones has observed that at this vital juncture it was necessary to abandon the Nevsky bridgehead and concentrate Red Army forces near Shlisselburg where conditions were more favourable for an attempt to break the German encirclement of the city, “But Zhdanov had neither the skill nor the experience to for see this possibility.”

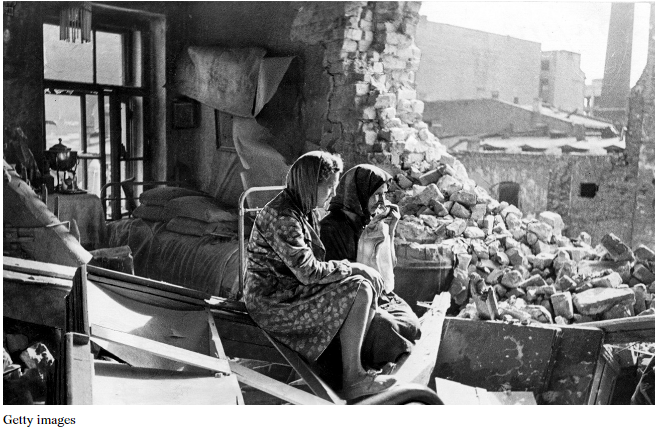

By now Leningrad was cut off from the rest of the Soviet Union. Siege lines had been drawn up around the city which would remain in place for the next sixteen months. To the north lay the Finns and to the south were the Germans. Under daily fire from heavy artillery and aerial bombardment the people of Leningrad began to sense that another more deadly foe was rapidly approaching.

German plans to annihilate the people of Leningrad

By late October a static war had developed on the Leningrad Front.

The Eighteenth German Army had dug in for a long siege. It's front line troops were accommodated in newly constructed dugouts and bunkers surrounded by a labyrinth of trenches, observation posts, barbed wire and firing positions. In the German rear were living quarters for the German army comprised of large bunkers with log walls and timber beams used for the roofs covered with soil for insulation. Inside these large bunkers were tables, wood burning stoves and bunks where soldiers could eat, sleep and relax. Beyond this, were the heavy gun emplacements which fired twice daily into the city of Leningrad. Behind the heavy gun placements the German army had built a mass of interconnecting roads, supply and ammunition depots to replenish their front line positions.

Field Marshal Leeb, the commander of German troops on the Leningrad front, decided to concentrate German heavy artillery between the towns of Uritsk and Volodarsky which were between five and seven miles from the front lines. From the rooftops of high buildings in these towns German artillery spotters enjoyed unobstructed views of Leningrad and were able to call down accurate fire into different quarters of the city.

The twice-daily German artillery barrage of Leningrad began at 10 am with a short intense barrage followed by another two hours of shelling at different locations in the city and then there would be a pause. This would be repeated again at 7pm every day. Field Marshal Leeb decided to inaugurate the daily methodical shelling of Leningrad by ordering an 18 hour barrage of the city on 17 September 1941.

On 28 September 1941 Field Marshal Leeb received an order from Berlin which stated German troops would not accept the capitulation of the city under any circumstances. This genocidal order called for the methodical destruction of all infrastructure which was essential to sustaining human life in Leningrad. The order from Berlin gave the following instruction to German troops laying siege to Leningrad:

In order to eliminate Leningrad as a centre of Bolshevik resistance on the Baltic without sacrificing the lives of our soldiers, the city is not to be attacked by infantry. It is to be deprived of its life and defensive capability by crushing its air protection and fighter planes, and then systematically destroying its waterworks food stores, and sources of power, any move by the civilian population in the direction of our troops should be prevented if necessary by force of arms.

As noted in part one, German occupying forces were not only intent on annihilating the people of Leningrad but were also committed to the genocide of civilians in the outlying villages and towns. Einsatzgruppe A worked closely with the German Eighteenth Army to eliminate Jews and all other civilians in the zone around German siege lines. Taking advantage of the growing food shortage in the Leningrad region German military police offered bread to starving civilians in return for which they would be sent into the city to gather intelligence for the German military.

In early October numerous German units began to ask for instructions concerning the starving population in their areas of operation. L Corps reported to Eighteenth Army that 20,000 people, “most of whom are factory workers, without food. Starvation is expected.” The quartermaster of the Eighteenth Army replied that “the provision of food by the troops and civilian population is out of the question.”

This reflected the thinking of the Nazi dictatorship's political and military leadership.

Hermann Goring, who was one of Hitler’s closest allies and head of the Luftwaffe, brazenly declared, “the fate of the great cities, especially Leningrad, is of absolutely no importance this war will witness the greatest starvation since the 30 years War.”

On 11 October 1941 Colonel General Kuchler, the Eighteenth Army's commander-in-chief, fully shared this thinking when he circulated the Reichnau Order amongst his soldiers. This genocidal decree explained to German soldiers what was expected of them in terms of their conduct on the Leningrad front. It declared:

The most essential aim of our war against Jewish Bolshevism is the complete destruction and elimination of the Asiatic influence from European culture. The soldier in the eastern territories is not merely a fighter according to the rules of war; he is also the bearer of a ruthless national ideology. Combating the enemy is still not been taken seriously enough. Feeding native inhabitants from army kitchens is a misguided humanitarian act.

During the course of October Field Marshal Leeb conducted extensive tours of his frontline positions in order to consult with his officers. Leeb became increasingly concerned about what to do if the increasingly hungry population of Leningrad attempted a mass breakout towards German lines. On 24 October senior officers from the German Eighteenth Army held a discussion about how to deal with this prospect. During the discussion it was reported that German soldiers may not keep their nerve when ordered to shoot defenceless women and children attempting to break out of the besieged city.

The war diary of Army group North reports on 27 October that the question of how to deal with Leningrad’s civilian population began to preoccupy Field Marshal Leeb. The war diary adds that Leeb was considering laying minefields in front of the German front lines in order to spare German soldiers from having to shoot down starving civilians at close range.

Finally, at the end of October, the commander of the German Eighteenth Army found a solution to his dilemma which was passed on to all artillery formations in front of Leningrad. The war diary of Army Group North recorded the decision of Leeb:

The commanding general visited a number of firing positions of heavy and light artillery batteries. He viewed the winter lodgings and newly constructed gun emplacements and then discussed with commanders the use of artillery to prevent the Russian civilian population breaking out from Leningrad. According to Army order 2737/Secret, such attempts are to be stopped if necessary by force of arms. It is the task of the artillery to deal such a situation, and as far away from our front lines as possible - preferably by opening fire on the civilians at an early stage [of their departure from the city] so that the infantry are spared the task to shoot civilians themselves.

The war diary of Army Group North on 15 November notes how this decision of Leeb’s was working in an efficient and satisfactory manner:

Some civilians who tried to get close to our lines were successfully hit by artillery fire.

During this period the Luftwaffe dropped macabre leaflets over the city addressed to the female population, “Put on your white dresses … Lie down in your coffins, prepare for death.”

The German army had drawn up accurate grid maps of Leningrad, which pinpointed targets for its artillery. For example, firing points 89 and 99 were hospitals, firing point 708 away was the Institute for Maternal Care, firing point 736 was an infant school, firing point 757 was civilian apartments on Bolshaya Street.

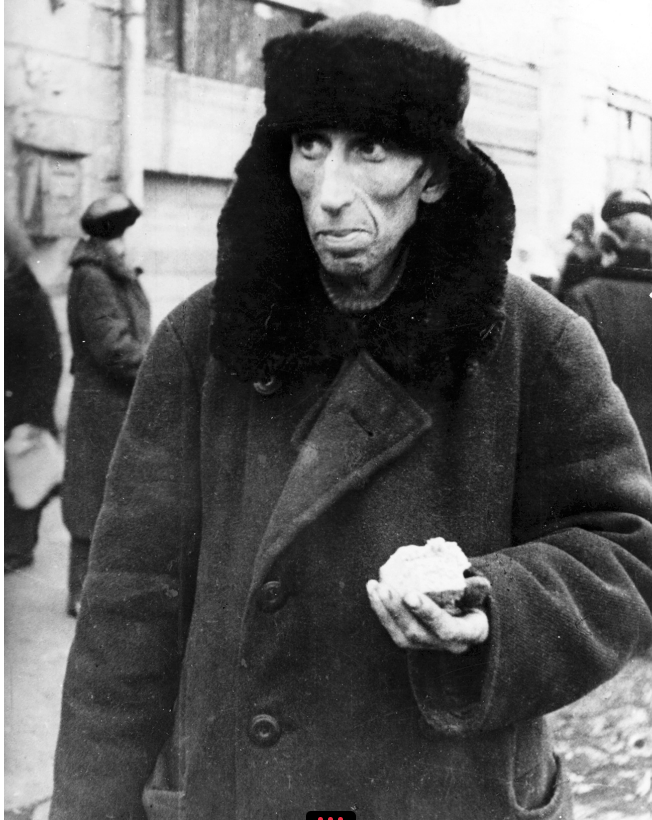

The Onset of Famine

As the civilian population of Leningrad became increasingly frantic and fearful about the approaching famine, German troops who were laying siege to the city were well fed and comfortable in warm front line bunkers.

Rations for front line German troops contained a generous amount of meat and potatoes along with plenty of bread, butter and cheese. The rations even included chocolate, vodka and even artificial coffee.

German troops knew full well they were starving a city of over 2 million people. On 30 October 1941 Lieutenant Thomas Berdahl sent a letter home to his family in which he mentioned the impending starvation of the Russian population:

The civilian population will suffer a great deal as fuel and food are not available. Our field kitchens over are already besieged. I see large-scale starvation coming. For one piece of bread, women work the entire day for us.

Sergeant Fritz Keppe of the second battery of the 910th Artillery Regiment testified later:

...for the bombardment of Leningrad our batteries received a special stock of ammunition, far beyond the average supplied to artillery units. It was almost an unlimited amount. On all our gun crews the purpose of the shelves: to destroy the city and wipe out the civilian population. We therefore regarded the bulletins of our Supreme Commander, who spoke of shelling the military objectives, with languor and ironic humour.

German artillery units not only knew that they were deliberately targeting the civilian population of Leningrad but began to display a growing sadism and relish for the murderous task to which they had been assigned.

Corporal Bakker of the 1st battery of the 768th Artillery Regiment later recounted;

We knew that there were a lot of civilians in the city and that we were mostly firing on civilian targets. We would joke as we were shooting saying ‘Hello Leningrad!’

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Kruschke of the 126th Artillery Regiment later recounted;

Our soldiers, who were shooting at city, would say, today we are feeding Leningrad again. They should be grateful to us - they have famine there, after all.

During these early days of the siege a growing number of Leningraders began to record their daily experiences in personal diaries. The city authorities had made an appeal for people to do this but many took up this task without any need for instruction from above. For many diary writing became an essential part of their survival, a way to find purpose and meaning as society began to collapse. Some diarists from the start regarded their writing as an essential task to preserve the historical record for future generations.

Semyon Putyakov noted in his diary on 7 October, 1941, “the situation with our food supplies is getting worse and worse. Our rations have been cut again.” Two days later he wrote, “Our soldiers are all saying that, in contrast to us, the Nazis are feeding very well. If that is true we are in big trouble.”

By late October he had noticed that the growing shortage of food was driving civilians to desperate measures putting their lives on the line in the search for scraps of food in the outlying countryside where they were very very vulnerable to German artillery fire:

It's awful to see women and old men desperately digging the same patch of land for the tenth time, trying to find a few potatoes.

October had been a hungry month for most but the real toll of famine began to appear in November as the city faced a grim winter ahead of them.