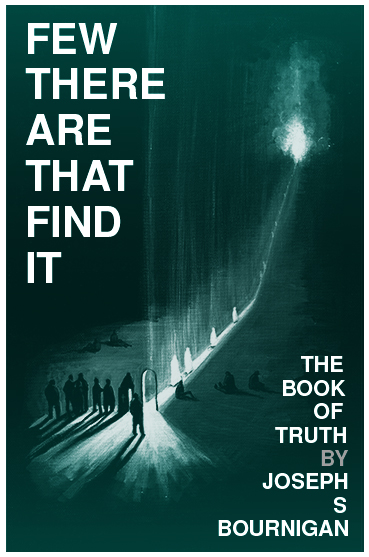

FEW THERE ARE THAT FIND IT

(The Book of Truth)

Chapter One

"Wandering Words"

The majority will fail to comprehend the message shared within these pages. It will not be due to a lack of clarity on my part, but a lack of commitment to understanding on theirs. This is because the unfortunate reality is that most of humanity have a considerably larger investment in comfort than in truth.

It is for the few who thirst for truth that I write this, in the hopes that you might find the path you were destined to walk without having to pay the heavy price that I did in order to attain this understanding. You will then have to decide upon whether or not you're willing to pay the even greater price that the message contained in this book will demand from you.

If my intention for you to know the truth is to be realised, I must first make it abundantly clear to you what is not the truth. The first portion of this book will be aimed at doing just that, beginning with the commonly believed but entirely incorrect notion that the surface level stories to be interpreted when reading the Torah, the Bible or the Quran, can be trusted on any level as an unsullied message from your Creator.

There are many rabbis out there who will tell you that the Torah is the preserved message of God. They will argue with a great deal of conviction that the message written by the authors has endured for thousands of years. Though we cannot be certain that the words written then are the ones that remain now, let's give them the benefit of the doubt and let us presume that those are indeed the exact same symbols and words written all those centuries ago.

The words being the same does not in any way mean that the message is the same. For words are but arrows; arrows that point to ideas. And if those arrows are no longer pointing to the same ideas, then we are no longer reading what was written.

To demonstrate the significance of this handicap of language, I would like you to consider the impact upon the message that a single word, or arrow, pointing in a different direction could cause. For the purposes of this demonstration, we are going to take a close look at a word used very often in the Torah - baal.

The word baal is synonymous with the words lord, master and husband. Essentially though, we understand all these words to mean owner.

If we sought through dictionaries in the hopes of discerning towards what idea this word or arrow "owner" is pointing towards, it may prove difficult. For a dictionary will tell us that an owner is someone who owns something, which is not much help. If we look up the definition of "own," we will find it to mean "possess." And if we look up the definition of "possess," we will discover it means "own." This is no use to us at all.

We could try and investigate the meaning of the word "belong" to find that it speaks to a relationship with property. But if we then search for the meaning of "property" we will find it leading us back to the word "possess." It is seemingly impossible to find a definition of the word owner that genuinely explains to us what it means to own something. This is very likely because, the modern understanding of the concept of ownership is entirely nonsensical.

To iterate my point I'd like you to imagine you're holding a bag of diamonds right now. You own them. Now imagine that someone approaches you and shoots you with a gun, killing you, and makes off with "your" diamonds. Where did your belief that you owned those diamonds get you exactly? They got you murdered, that's where.

Let's take this a step further. For if there is one thing that we can say, this, I definitely own; this is my property - it would be our body. But there is this thing we call rape, which is when another person decides that what you believe to be your body is actually their body. So where did your belief, that you owned your body, in this instance get you? It got you traumatised.

If we really want to know what the word owner means, we need only study our behaviour as it relates to the things we believe we own. In doing so, I think it fair to say that to own something in modernity, essentially means; This is mine to break - not yours.

You may wish to disagree with me, but this is surely what it means. And if we again observe how the majority of us treat the one thing we can all be certain is our "property," our bodies, this will become very clear. If I wish to damage my body by overeating, drinking alcohol, smoking or doing drugs, then most would agree that I'm entitled to - because it's my body. But if someone else tried to damage my body, against my will, we can agree that is not acceptable. Because I can break this - but you cannot.

It is through this perverted understanding of what it means to own something that many religious men find justification to mistreat their wives. For by the modern interpretation of the word, ownership is inexplicably linked to the concept of property. And the notion of property is inseparable from that of ownership. So what is a believer to think when the word baal, which we know to mean owner, is used to describe a husband in the Torah? We would of course think, since ownership, by our twenty first century understanding, is tied to property, that if the husband is the owner then the wife is the property. It does not matter that the word used for wife does not translate to property. A man looking for an excuse to mistreat his woman will interpret this passage as the Almighty Himself commanding him to treat his wife as he would any other things he believes he "owns."

This is why in certain denominations of the Abrahamic religions, women are treated very poorly. But I'd like you to consider that the word owner, or I should say, the word baal, did not in its conception mean what it does to us today, but in fact meant something far closer to someone who is responsible for the well being and longevity of a person or a thing.

How different would the world be if we understood the words owner and master and lord to be synonymous with wilful servant, protector or someone who has taken responsibility for someone or some thing? There are perhaps echoes of this notion in our language still, for we use the word "own" on occasion to speak towards the notion of responsibility. Think; "I take ownership of my mistakes."

Assuming this be true, the impact this one perversion of a word has had upon our world is huge. It has corrupted almost every aspect of our lives. Imagine how differently we might treat our women if we understood that taking ownership of them meant that we were taking upon our shoulders a duty towards ensuring they had the best lives possible? How differently would we treat our own bodies if we thought that owning them meant we were entrusted to take responsibility of them? Would we still poison ourselves with bad food and drugs? Would we allow them to fall into disrepute through a lack of exercise? Would we desecrate them by committing fowl deeds? If it did not carry with it a sinister connotation when we said the word "mine," but instead implied a sense of duty and responsibility, would we be fighting over resources and attempting to measure the things we "possess" against the things that others do or do not? Or would we be eager to share with our neighbours, no matter how distant, knowing that in doing so we are relinquishing a burden rather than losing an imagined piece of ourselves?

If the meaning of this word has been corrupted in this way, one would also need to reconsider whether the slave owners of antiquity were really men collecting organic "property," or men who had made a commitment to feeding and housing and taking care of others who were incapable of taking care of themselves.

I cannot prove to you, unfortunately, that this was the original meaning of the word baal. It is impossible for me to say even to myself with absolute certainty that it was to this idea that arrow once pointed, even if I know it to be true in some sense. But, I do not need to prove it did. Not to you, and not to myself. For the simple truth of the matter is - it could have. And if the meaning of a single word becoming corrupted could potentially have such a drastic impact upon the message of the Torah and upon our entire world, then when considering the amount of words that are contained within the Torah, how can we possibly say with any level of confidence that the message of the authors has been preserved - and not just the words?

The same argument can be made against any claim that any scripture is the preserved message of God. An imam would likely attempt to convince you that this problem with the meaning of words does not apply to the Quran because Islam has a bibliographic library that dates back to the authoring of the scriptures, and that by studying it, one can observe the changes of the meaning of the words used over time. But, this would be a weak claim to make. For, the same problem applies to the texts that apparently record the evolution of language, and because there is no way for us to be certain that those texts were written when we were told that they were anyway.

So, there is no ancient text that we can be sure still contains the same message, at least on the surface, as it did when it was penned. And to argue that any scripture is the preserved message of the Creator, is an argument against, not in favour of truth.

Follow fallfromdisgrace to keep up with the chapters of this book.