A few months ago, it looked like the Russian economy was outperforming expectations, but today things aren't quite as rosy. When Putin first invaded in late February, the West imposed an unprecedented sanctions regime on the country, including cutting certain Russian banks off from the global financial system and seizing some $300 billion worth of offshore central bank assets. Originally, it looked like these sanctions had worked; the ruble collapsed, the Russian stock market closed, and there was some speculation that Russia was on the cusp of a financial crisis akin to that of the late 1990s. However, over the subsequent months, the economic outlook in the country has begun to improve. A combination of record hydrocarbon exports and interventionist economic policy pushed the ruble to a two-year high and allowed the Russian state to run a healthy budget surplus, which it used to finance its invasion of Ukraine. Now, this isn't to say that everything was rosy from the Kremlin's point of view. At the time, the ruble's strength was artificially inflated by new rules from the central bank requiring all exporters to give up their foreign currencies, and certain sectors really weren't holding up well, including finance and car manufacturing.

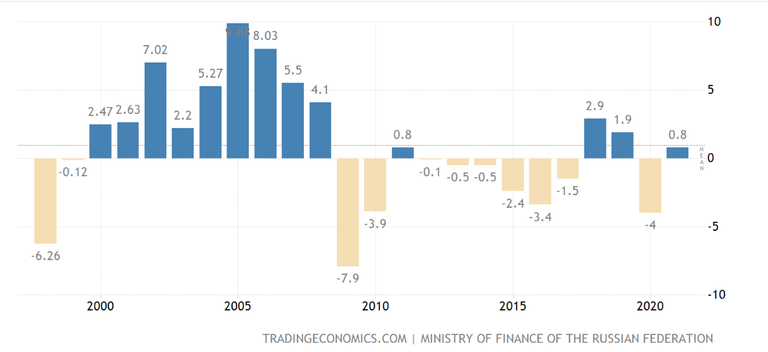

Nonetheless, the Russian economy did outperform at least the most pessimistic expectations, and its GDP forecasts, which were originally predicting a record-breaking recession, were revised upward. For example, the IMF predicted in April that the Russian economy would experience an 8.5% contraction, but this was upgraded to 6% in July, and the latest forecast from October now only predicts a 3.4% contraction. Unfortunately for the Kremlin, though, over the last month or so, Russia's economic outlook has deteriorated significantly. Inflation remains stubbornly high at nearly 13 percent, and preliminary data released last week by Rostat, Russia's national statistics institute, suggests that the Russian economy shrank by four percent year-on-year in the third quarter, meaning that Russia has formally entered a recession. On top of that, falling global oil prices and reduced European demand for Russian gas have meant that Russia's budget surplus has started shrinking, which will make financing the war significantly more difficult going forward.

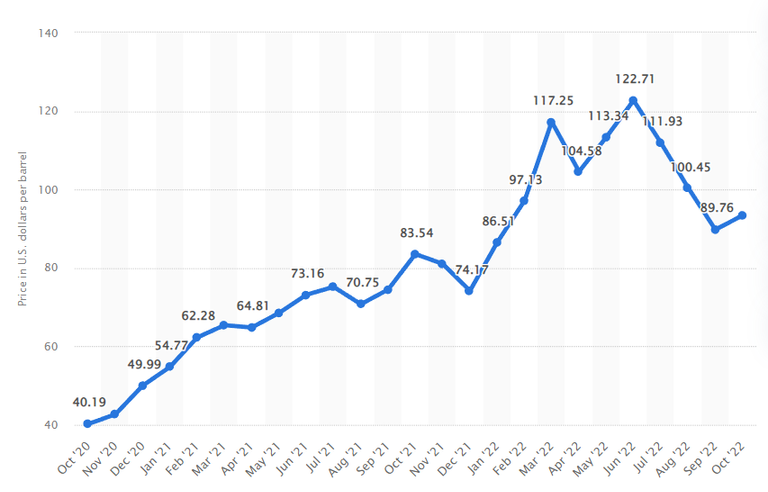

As we see it, there are three reasons that Russia's economic outlook is deteriorating: falling oil and gas prices, sanction-induced shortages, and human capital flight. Let's start with falling oil and gas prices. When Putin began his invasion, Brent Crude, the world's benchmark for oil prices, was trading at about $100 per barrel. Now, in part due to the geopolitical uncertainty created by this war, in the subsequent months, prices rose even higher, reaching a fairly stable high of about $123 by mid-June. Now, this was obviously good news for Russia, given that it's the world's second-largest exporter of oil after only Saudi Arabia. And in even better news for them, gas prices followed a similar pattern. European gas prices were already pretty high going into the war. In the days before Putin invaded on February 24th, the Dutch TTF, which is the benchmark for European gas, was already trading at about 80 euros per megawatt-hour. For context, for most of 2021, the TTF was trading at about 20 euros. However, in the months following the invasion, as European countries desperately tried to stock up on gas before the winter, prices skyrocketed, reaching a high of about 350 euros in mid-August.

Now, even though Russia was selling its oil at a discount, these high oil and gas prices were still great news for Russia. An analysis by the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air found that Russia's hydrocarbon export revenues were about 20 percent higher than average, running at nearly 1 billion euros per day. These enormous revenues allowed the Kremlin to run a massive budget surplus. For context, in January, Russia's budget surplus was a little over 250 billion rubles, but in June, when oil prices were reaching their peak, it was five times that at about 1.4 trillion rubles. And this money was crucial, giving Putin the fiscal space to continue and expand his invasion of Ukraine. However, in the past month or so, oil and gas prices have started falling, and as you'd expect, Russia's budget surplus has suddenly dried up. Thanks largely to reduced demand from China and a global recession, Brent Crude is now trading at just over $80 per barrel, well down from its June highs. Similarly, thanks to an average mild winter and a well-coordinated European gas storage initiative, Dutch TTF has dropped to a little more than 100 euros per megawatt hour.

Now, while that's still way higher than the pre-war average, it's down 60% from its August peak, and it's also worth mentioning that Russia is exporting less gas than it once did. Russian gas exports to Europe have fallen by about 80 percent, from 2.5 billion cubic meters in February to about 500 million today. Now, lower oil and gas prices combined with reduced export volume obviously imply lower revenues, which is why Russia's budget surplus has relatively quickly dried up. In October, Russia's budget surplus sat at just 50 billion rubles, down an astonishing 95 percent from the 1.4 trillion high achieved in June, and that's really important because falling revenues undermine Russia's ability to finance its war in Ukraine, especially because sanctions have limited Russia's ability to borrow on the global financial markets.

Let's move on to the second reason that they're struggling: sanction-induced shortages. When the Russian economy was outperforming expectations, the Russian state media was full of triumphant headlines about the apparent inefficiency of Western sanctions. However, as Russia's Central Bank acknowledged at the time, sanctions were never going to have an immediate impact because Russian industry could rely on stockpiles to see it through the first few months. However, as predicted, dwindling stockpiles have now given way to shortages, and it's clear that Russia is getting increasingly desperate for certain parts, especially semiconductors. While Russian companies have tried to mitigate the impact of sanctions by increasing imports from China, the fraction of 40 component imports has apparently increased from 2 to 40 percent, according to a report from October.

This is presumably because reputable Chinese companies are refusing to trade with Russian businesses for fear of either reputational damage or secondary sanctions, leaving Russia reliant on less dependable Chinese companies. Faced with severe shortages and no reliable source of imports, Russian authorities started stripping planes for parts back in August, and in the last month or so, evidence has emerged that Russia is smuggling in European-made appliances like fridges, washing machines, and even breast pumps to get their hands on much-needed components. As well as pushing up electronics prices generally, these shortages will also undermine Russia's ability to manufacture military hardware and weapon systems, which is clearly crucial for the war.

The third and final issue Russia is facing is the flight of human capital. Any modern economy relies on highly trained and specialized workers, but since Putin announced his invasion in February, thousands of these workers, representing a significant fraction of Russia's human capital, have fled the country. It's estimated that between 250,000 and 500,000 Russians, mostly men of military age, fled the country in the first six months of the war, and according to British intelligence, a further 170,000 or so have fled in response to the partial mobilization announced in late September. The thing is that those fleeing will be, in general, wealthier and better educated than the average Russian. Obviously, losing tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of well-educated young men will significantly reduce Russia's human capital. On top of that, this exodus will have a tightening effect on the labor market and put upward pressure on inflation, which is already well above the central bank's target.

In conclusion, all of these factors—reduced revenues, component shortages, and the recent Exodus—will undermine Russia's economy and, as such, their ability to wage war. This is because reduced revenues limit the amount of money that Putin can spend on the invasion itself. This might go some way toward explaining why, for the budget for 2023 released in September, Russia only announced that military spending would be increasing by 40 percent, the equivalent of just 4.5 percent of GDP. While this might sound like a lot given that the partial mobilization has increased the total troop numbers by 30 percent, it's not a significant increase in spending per soldier. On top of that, it's worth saying that historically, winning a full-scale war has required spending more than five percent of GDP, something that Putin hasn't committed to and might not be able to do. So if Putin's economy continues to struggle, then his war effort could get increasingly complicated.

War booty .will remain forever.the art of war is not just about money .

You cannot prove that the wheels of the Russian economy are running smoothly just by posting a news source link and an inflation chart published by the Russian state authority. Any individual who has taken Economics 101 or has basic economic literacy can tell you that these data are insufficient.

Moreover, Russia is a raw material exporter. This is the reason why inflation in Russia can still remain at low levels despite the sanctions, and I did not argue the opposite. The Russian people may find potatoes, vodka and bread, but they cannot find many products such as spare parts, phone, tablet computer components or they have to buy them at very high prices.

As for the European Union's lng purchase, the data I have shows that the eu has made the lowest lng imports in the last month since october 2021 1.100 million cubic meters (august)

It also represents a very small amount of LNG for the transport of Russian gas to the European Union. eu receives gas through the main pipelines, of which the vast majority supply gas far below their capacity. The only line that works at almost full capacity is the bluestream and turkstream lines passing through Turkey, and their capacity is very low compared to nordstream 1 and 2.

According to my source the EU imported about 30% more Russian LNG compared to last year

https://www.duurzaamnieuws.nl/waarom-nederland-nog-steeds-lng-uit-rusland-koopt/

"Het is niet geheim maar niemand praat er over: terwijl de levering van Russisch aardgas via pijpleidingen dramatisch is gedaald, is de invoer van vloeibaar aardgas LNG uit Rusland in de EU gestegen. Dat blijkt uit cijfers van de Europese Commissie die Politico heeft ingezien. EU-landen hebben tussen januari en september 2022 16,5 miljard kubieke meter (bcm) Russisch LNG ingevoerd, tegenover 11,3 bcm in dezelfde periode vorig jaar. Een flink deel daarvan was bestemd voor Nederland."

btw i upvoted you on accident lolz