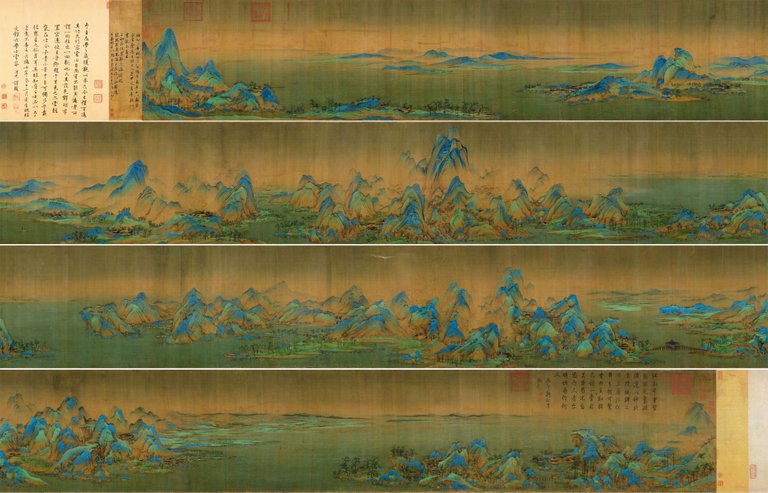

The various ways of viewing the natural environment and the rules of the six distances are often all used simultaneously in the same painting. All of these methods combined, it enables the artist to better represent the complexity of the natural scenery. For instance, let's take one of the most famous works in the history of mountain and water painting, by Wang Ximeng (王希孟, 1096–1119). He was one of the most renowned court painters of the Northern Song dynasty, who painted a 51.5 cm and 11.9 meters long scroll titled A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains 《千里江山图》.

This work was made on silk, revealing the lake and river scenery of the mountain complex of Mount Lu 庐山, in Jiangxi province. The mountains are signified by the use of green and blue. Misty and vast, the scenery ever-changing and magnificent. On the mountain, there are high cliffs and waterfalls, winding and quiet, red flowers, green willows, long pines and bamboo trees. In addition to the beauty and executive finesse, the painting also has an enormous narrative charge, describing a cross-section of a twelfth-century rural life in China. In order to represent the richness of the area developed around Mount Lu, the artist uses all of the perspective and visual expedients that we have just illustrated. The great mountains are represented through height distance, the valleys and rivers that extends into the deep are represented through deep distance and the low mountains and hills that develop in the distance through level distance. The river is particularly suited to the three distances rule of Han Zhou, we find distant mountains behind a large stretch of water in the broad distance, and the inaccessible scenarios of the remote distance and the mysterious and dreamlike ones of the shrouded distance. The artist certainly had crossed the area to be able to understand its development and training. He had observed it from a distance to understand its structure, which as Su Dongpo reminds us in the last two verses of the poem On the walls of Xilin: “I can't see the real aspect of Mount Lu, since I am between its mountains ","不识庐山真面目,只缘身在此山中", referring to the concept of "looking at the big through the small". Wang Ximeng observed the area of Mount Lu closely to grasp its details, it accompanies us in a microcosm rich in life, catapulting us into the rural society of central-eastern China 800 years ago. The painting is animated by about 360 characters, whose size does not exceed half a centimetre. Many of them are fishermen or travellers on foot who travels the many roads on the vast plains and mountains, the same path that Wang Ximeng himself travelled. We can see inns, bridges, places of worship and around a hundred boats used for travelling. We can also see almost 30 villages hidden in the mountains and by the river. The buildings are represented following different perspective rules, which adapt to the general harmony of the composition. The painting also displays the importance of fishing in the society during that time. In addition to the numerous fishermen on boats and along the shore with the rod, we can also see trabuccos and fish farms near the fishing villages. There are also several places of leisure with cultural activities, such as study centres and pavilions on top of the promontories where it would’ve been possible to admire the mountain and river landscape, creating a sort of meta-landscape. We see how the richness and complexity of the work is closely linked to the way in which the environment is observed. Such a painting would be impossible to create using the unifocal perspective or simply observing the area from a single point of view, it would involve a profound knowledge of a vast area through different methods of observation and consequently of representation.

Certainly, a single static point of view is not the means to represent nature and its complexity. Therefore, since the earliest times Chinese artists have endeavoured to find techniques to visually represent the variety and depth of their subject. When the eye of the observer settles on a work composed following these canons, the visual experience will not remain static, because a centre of attraction such as that of the focal perspective will not be present and it would be impossible to observe the whole work without movement, thus cancelling the instantaneousness of the visual experience. This movement will lead him to interact with the work and to feel part of it and not as an external observer. This is precisely because the painter did not interact with the environment as if it were external to it, but lived through it. Many famous painters spent part of their life in the mountains, such as Jing Hao 荆浩 (850-911) in the area of Mount Taihang 太行山 where it was said that he painted tens of thousands of pine trees, or Fan Kuan 范宽 (950-1032) at Mount Zhongnan 终南山, in order to know its secrets and learn to paint natural elements. This attitude of appreciation of the wild natural environment is at the basis of the great development of the mountain and water painting, an attitude that did not exist in the West at least until modern times. But in China, there was the will to know and understand these kinds of environments that inspired wonder and mystery since ancient times. This can be proven in the compilation of texts such as the Classic of the mountains and seas 《山海经》, probably composed in the fourth century BCE, a text that encompasses geographical, mythological, medical notions related to mountainous areas, seas and wild areas inside and outside of Chinese territory. The same appreciation for wild nature is found in sentences pronounced by Gu Kaizhi 顾恺之, a famous painter of the fourth century, who was amongst one of the first to apply himself to the mountain and water painting, referring to the beauty of a mountain area: “thousands of rocks compete for beauty , thousands of valleys compete for flow ","千岩竞秀,万壑争流 ". So, this appreciation of the mountains, which we have found since the most remote periods of Chinese culture, has led them to admire the mountain environments and not to fear them, as happened for most of the development of western culture, especially towards the Alps. Here another chapter would open on the relationship between nature and man in the West and in China which will be treated elsewhere.

For these reasons it is not suitable to use the term landscape when referring to the mountain and water painting, the term landscape in the mentality and in western languages, brings with it a whole series of elements, which has only been partially treated, ranging to come into conflict with the relationship Chinese artists have with nature and how to express it pictorially. The absence of the use of the mono focal perspective frees the work from the yoke of anthropocentrism, which severely limits the perception of nature as an extremely vast and complex entity, which cannot be reduced to the mere perceptual rules centred around the artist ego. This problem soon appeared to Chinese artists and theorists of painting, which led to a long and rich reflection that implicitly questioned the limits of sight and how to overcome them, often by bending the visual laws to artistic needs, in order to be able to express pictorial subjects as complex as the natural environment. In conclusion, it should be remembered that in the theory of Chinese painting, representing what you see as you saw it has never been the artist's goal. Indeed this practice was always highly criticized in the texts concerning painting, a famous verse by Su Dongpo quotes: "who discuss painting in terms of form likeness, has the understanding of a child", "论画以形似,见与儿童邻", since all the things are characterized by form (external appearance) and spirit, as Jing Hao in the Notes on Brushwork 《笔法记》said: “the form without the spirit is a dead form”, “凡气传于华,遗以象,象之死也”.

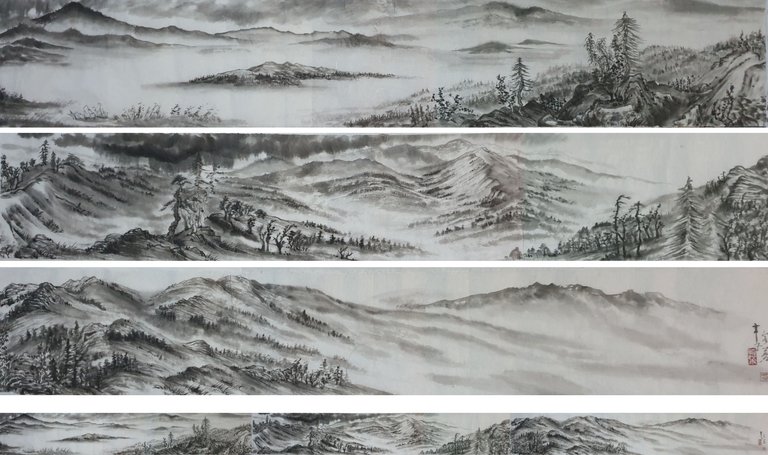

From Trasimeno lake to mount Tezio,

Check out more of my works - Xuan paper, Chinese ink, 22x422, 2021

https://saurosefolli.wixsite.com/giacomoshan/selezione-di-lavori

or follow me on Instagram @giacomofumo