Puntos Lagrange del Sistema Sol-Tierra / Lagrange Points of the Sun-Earth System Fuente / Source

Español

Puntos de Lagrange

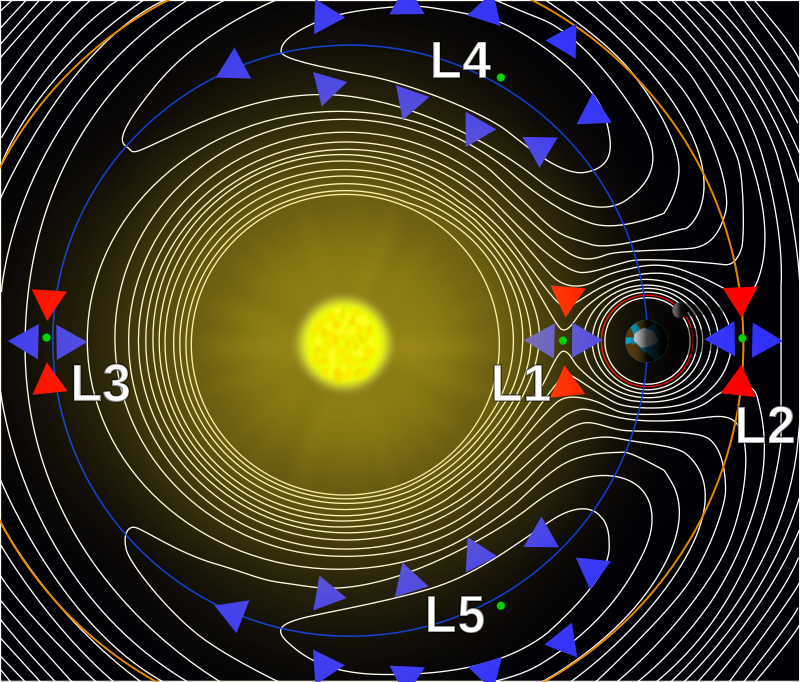

Existen varios puntos de la orbita de un objeto masivo que gira alrededor de otro de mayor masa, en los cuales, sus campos gravitacionales se equilibran, de tal forma que la fuerza centrípeta en ellos permite a un objeto, de masa despreciable, en relación a la de los otros dos, orbitar al cuerpo mayor, en sincronía con el de menor masa, estos puntos son los llamados puntos Lagrange y son exactamente cinco, denotados por L1 a L5. [1][4]

Si bien un objeto cualquiera puede compartir la órbita con otro mayor, estas relaciones no suelen ser del tipo sincrónicas, es el caso de los satélites, que están sujetos a la influencia del campo gravitacional del objeto al cual orbitan y lo acompañan en su órbita alrededor de otro mayor, pero no existe sincronía en su órbita.

También puede ocurrir que un cuerpo, de masa muy pequeña, se adhiera a la órbita de otro mayor, y lo acompañe sincrónicamente durante algún tiempo, pero si no está situado en uno de estos puntos, terminará tarde o temprano siendo expulsado de su órbita o dependiendo de su posición, colisionando con el objeto de mayor masa.

Una situación interesante es en la que un objeto de masa considerable, comparte la orbita de otro con el cual está en sincronía, situado en uno de los puntos Lagrange, este tipo de interacciones suelen ser temporales pues tarde o temprano la interacción del campo gravitacional del objeto, lo hará ser expulsado o caer en el campo gravitacional del objeto mayor con el que comparte la órbita, tal es el caso de los denominados Planetas Troyanos, que viajan en los puntos L4 o L5 de un planeta de mayor masa. [6]

Un ejemplo de esto último es Teia, un hipotético planeta troyano de un tamaño similar al de Marte que orbitaba junto a la Tierra en el sistema solar primitivo, ocupando una posición del punto Lagrange 4 o 5 (L4 o L5), que tras acompañar sincronizadamente a nuestro planeta por algún tiempo, su órbita poco a poco terminó decayendo afectada por la influencia de algún agente externo, como el campo gravitacional de Venus o Júpiter, por lo que terminó colisionando con la Tierra, dando lugar a la casi destrucción de la Tierra primitiva y la expulsión de gran cantidad de materia al espacio, que constituiría un disco de acreción alrededor de ésta, el cual se terminó consolidando en lo que hoy es la Luna. [2]

Los puntos L fueron calculados en 1772 por el matemático italofrancés Joseph-Louis Lagrange, quien trabajaba en una solución al problema de los tres cuerpos, el cual es un clásico problema matemático, que consiste en calcular simultáneamente la posición y velocidad de tres cuerpos de diferentes masas que se mueven afectados por la atracción gravitacional mutua, dada la velocidad y posición inicial de los mismos. En consecuencia, los puntos Lagrange son las cinco soluciones posibles a este problema, cuando los objetos tienen órbitas casi circulares. [4][3]

Lagrange se planteó la posibilidad de tener un sistema en el que los cuerpos tuviesen orbitas casi circulares e incluir en él un tercer cuerpo de masa despreciable, el cual pudiese seguir una órbita también casi circular, de mínimo cambio en el tiempo, lo que le llevo a encontrar cinco soluciones posibles, de posiciones, en las que el cuerpo, desplazándose una velocidad similar a la del menor de los dos cuerpos principales, podría mantener una órbita más o menos estable en el tiempo. Estas cinco soluciones son los denominados puntos L1 a L5 [4]

De los puntos Lagrange resultan de especial interés para la astronáutica los puntos L1 y L2, pues permiten posicionar artefactos que permanecerían en órbitas más o menos estables, por mucho tiempo, recibiendo siempre misma cantidad de energía solar, lo que les brinda una fuente continua para la generación de electricidad. Al mismo tiempo estas localizaciones los posiciona en ubicaciones donde están más o menos alejados del polvo o partículas, que regularmente cruzan en la proximidad de la influencia gravitacional terrestre. Además, de proporcionarles una vista continuamente despejada del espacio. Por esto, ambos puntos son de especial interés para el posicionamiento de instrumentos astronómicos. [1]

Por su parte los puntos L4 y L5, son los únicos realmente estables del sistema. Cualquier objeto artificial que sea situado en alguno de los otros tres deberá hacer correcciones ocasionales de posición, para evitar terminar siendo expulsado con el tiempo. Sin embargo, en los puntos L4 y L5, estas correcciones no son necesarias, cualquier objeto que se encuentre en sincronía con la órbita de la Tierra en esos puntos permanecerá ahí permanentemente, al menos que alguna influencia externa altere su curso. [1][5]

Lo anterior hace que los puntos L4 y L5, tiendan a acumular partículas de muchos tamaños, desde polvo hasta asteroides, por lo que no son adecuados para el posicionamiento de artefactos astronáuticos, la Tierra, al igual todos los planetas del sistema solar, tienen pequeñas nubes de objetos naturales, que los acompañan en sus órbitas, en los puntos L4 y L5 siendo denominados Troyanos. [5]

EL nombre de Troyanos se les atribuye a estos objetos, pues por convención se decidió dar el nombre de personajes de la guerra de Troya a los asteroides que se sitúan en los puntos L4 y L5 de la órbita de Júpiter los cuales son todo un sistema formado por más de 4000 objetos, que van del tamaño del polvo hasta los 102 kilometro de radio de Héctor, el mayor de los asteroides troyanos, siendo este el mayor sistema de asteroides Troyanos del Sistemas Solar. [5]

English

Lagrange points

There are several points in the orbit of a massive object revolving around another of greater mass, in which their gravitational fields are balanced, so that the centripetal force in them allows an object of negligible mass, relative to that of the other two, to orbit the larger body, in synchrony with the lower mass, these points are called Lagrange points and are exactly five, denoted by L1 to L5. [1][4]

Although any object can share an orbit with a larger one, these relationships are not usually of the synchronous type, as in the case of satellites, which are subject to the influence of the gravitational field of the object they orbit and accompany it in its orbit around a larger one, but there is no synchrony in its orbit.

It can also happen that a body, of very small mass, adheres to the orbit of a larger one, and accompanies it synchronously for some time, but if it is not located at one of these points, it will sooner or later end up being expelled from its orbit or, depending on its position, colliding with the object of greater mass.

An interesting situation is in which an object of considerable mass, shares the orbit of another with which it is in synchrony, located in one of the Lagrange points, this type of interactions are usually temporary because sooner or later the interaction of the gravitational field of the object, will make it be expelled or fall into the gravitational field of the larger object with which it shares the orbit, such is the case of the so-called Trojan Planets, which travel in the L4 or L5 points of a planet of greater mass. [6]

An example of the latter is Teia, a hypothetical Trojan planet of a size similar to Mars that orbited next to Earth in the early solar system, occupying a position of Lagrange point 4 or 5 (L4 or L5), which after synchronously accompanying our planet for some time, its orbit gradually ended up decaying affected by the influence of some external agent, such as the gravitational field of Venus or Jupiter, so it ended up colliding with the Earth, resulting in the near destruction of the primitive Earth and the expulsion of a large amount of matter into space, which would constitute an accretion disk around it, which ended up consolidating into what is now the Moon. [2]

The L points were calculated in 1772 by the Italian-French mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange, who was working on a solution to the three-body problem, which is a classical mathematical problem, consisting in calculating simultaneously the position and velocity of three bodies of different masses moving affected by mutual gravitational attraction, given their initial velocity and position. Consequently, Lagrange points are the five possible solutions to this problem, when the objects have nearly circular orbits. [4][3]

Lagrange considered the possibility of having a system in which the bodies had almost circular orbits and including in it a third body of negligible mass, which could follow an orbit also almost circular, of minimum change in time, which led him to find five possible solutions, of positions, in which the body, moving a velocity similar to that of the smaller of the two main bodies, could maintain a more or less stable orbit in time. These five solutions are the so-called L1 to L5 points [4].

Of the Lagrange points, the L1 and L2 points are of special interest for astronautics, since they allow positioning devices that would remain in more or less stable orbits, for a long time, always receiving the same amount of solar energy, which provides them with a continuous source for the generation of electricity. At the same time these locations position them in locations where they are more or less far away from dust or particles that regularly cross in the vicinity of the Earth's gravitational influence. In addition, it provides them with a continuously unobstructed view of space. For this reason, both points are of special interest for positioning astronomical instruments. [1]

L4 and L5, on the other hand, are the only truly stable points in the system. Any artificial object that is placed in any of the other three will have to make occasional position corrections to avoid being ejected over time. However, at points L4 and L5, these corrections are not necessary; any object that is in sync with the Earth's orbit at those points will remain there permanently, unless some external influence alters its course. [1][5]

This means that the L4 and L5 points tend to accumulate particles of many sizes, from dust to asteroids, so they are not suitable for the positioning of astronautical devices, the Earth, like all the planets of the solar system, have small clouds of natural objects, which accompany them in their orbits, in the L4 and L5 points being called Trojans. [5]

The name Trojans is attributed to these objects, because by convention it was decided to give the name of characters of the Trojan War to the asteroids that are located at points L4 and L5 of the orbit of Jupiter which are a whole system formed by more than 4000 objects, ranging from the size of dust to 102 kilometer radius of Hector, the largest of the Trojan asteroids, this being the largest system of Trojan asteroids in the Solar Systems. [5]

Referencias / Sources

- Astronoo, Los puntos de Lagrange L1 L2 L3 L4 L5, Astronoo.

- Wikipedia, Tea (planeta), Wikipedia.

- Wikipedia, Problema de los tres cuerpos, Wikipedia.

- Wikipedia, Puntos de Lagrange, Wikipedia.

- Wikipedia, Asteroide troyano, Wikipedia.

- Wikipedia, Planeta troyano, Wikipedia.

Space math is always intriguing

!1UP

You have received a 1UP from @gwajnberg!

@stem-curator

And they will bring !PIZZA 🍕.

Learn more about our delegation service to earn daily rewards. Join the Cartel on Discord.

I gifted $PIZZA slices here:

@curation-cartel(12/20) tipped @amart29 (x1)

Please vote for pizza.witness!

Thanks for your contribution to the STEMsocial community. Feel free to join us on discord to get to know the rest of us!

Please consider delegating to the @stemsocial account (85% of the curation rewards are returned).

You may also include @stemsocial as a beneficiary of the rewards of this post to get a stronger support.

Su post ha sido valorado por @ramonycajal