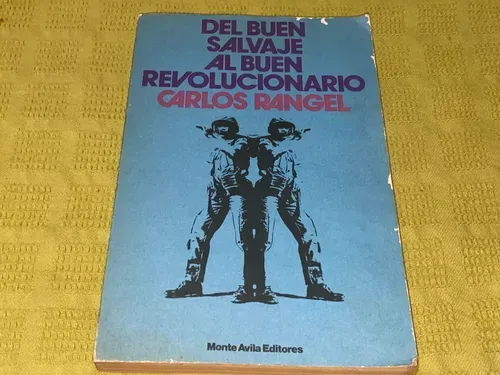

Anytime I think about Latin America I find traces of stories I once believed without question. Reading Carlos Rangel’s book felt like walking into a room where every comforting lie had been quietly removed. The figure of the good savage had always seemed almost noble in textbooks and lectures but Rangel forces me to see it for what it is: a myth built to excuse inaction and maintain dependency. I could feel the weight of centuries of borrowed ideas that painted innocence over complexity and passivity over responsibility. The shock is not only intellectual but personal because it demands that I recognize how deeply these illusions have shaped my own understanding of my society.

Bringing myths into daylight is never comfortable. The good revolutionary is even more insidious, appearing as a symbol of moral perfection while masking the destruction it causes. I felt a tension between admiration and disgust because I had once allowed myself to romanticize rebellion without examining its consequences. Rangel does not allow that luxury. His arguments cut precisely, showing how idealizing revolutionaries can justify tyranny, chaos, and economic stagnation. I found myself revisiting moments in history and current politics where we have elevated violence or suffering into a virtue, realizing how seductive these simplifications have been.

Critique in this book is always paired with responsibility. Progress cannot come from nostalgia or myth. Rangel insists that development requires institutions, transparency, and a clear recognition of human flaws. I found myself challenged by the idea that there are no external saviors or universal answers but only the work we choose to undertake ourselves. The text made me confront the gap between ideas and action, reminding me that ignoring facts for the sake of comforting stories only perpetuates decay. It is a sharp call to see clearly and act intentionally.

Every argument exposed how identity can be manipulated by symbols and ideals. I saw how the myths of the good savage and the good revolutionary have served to excuse both failure and cruelty, often simultaneously. Rangel holds up a mirror that is precise and unforgiving yet profoundly human. I felt the discomfort of recognition but also the clarity that comes with seeing a distorted culture and self honestly. The book demanded introspection not only about Latin America’s past but also about my own complicity in perpetuating unexamined beliefs.

Finally I closed the book aware of both the responsibility and the possibility that come with truth. No myth can be left unquestioned and no idealized figure should be trusted without scrutiny. Rangel’s work is not a consolation but a challenge: to think critically, abandon false narratives, and engage with reality on its own terms. I was left unsettled yet empowered because confronting myths is painful but necessary. On Good Savages and Good Revolutionists reminds me that liberation begins with clarity, courage, and refusal to accept comfortable lies. It is a book that does not flatter but transforms by forcing honest engagement with history, culture, and personal accountability.

All photographs and content used in this post are my own. Therefore, they have been used under my permission and are my property.