Hello Hivers and Book Clubbers,

Back with another review for the Book Club. The last few books read, and in turn articles written, were on subjects I wasn't familiar with at all. This one brings me into very familiar territory, as I'm very interested in South-African history, specifically that of the Afrikaners.

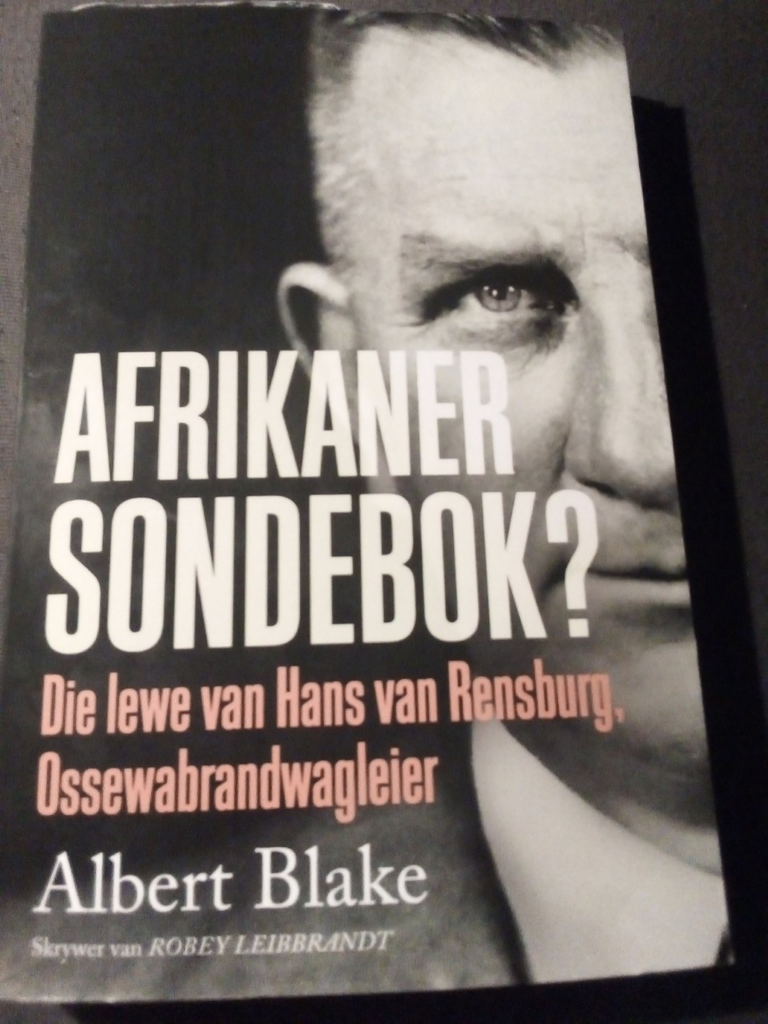

The book I'm reviewing today is fully titled 'Afrikaner Sondebok? Die lewe van Hans van Rensburg, Ossewabrandwagleier'. Translated to English it means 'Afrikaner Scapegoat? The life of Hans van Rensburg, leader of the Oxwagon-Sentinels'. This is a new study by Albert Blake, who has a position in the University of the Free State, and the study is released in both English and Afrikaans.

I got my hands on a paperback Afrikaans copy through Amazon. From a linguistic point of view; Afrikaans as a language has a vocabulary that is about 90% similar to Dutch, my mother tongue. Grammar is also very similar. Once you get used to it with some practice, it's quite easy to read Afrikaans as a Dutchman. I can recommend it to any Dutchies in the Hive-sphere to try sometime.

Biography

The book is structured as a biography, going chronologically through the life of Hans van Rensburg (1898-1966), while taking sidesteps to talk about important moments and events in South African history, and how Van Rensburg himself interacted with them. I'll be doing the same in this review, to give context to the events, because it's the most complete way to learn about Afrikaner/South African history.

Van Rensburg was born in a country on the brink of war. He was born in Winburg, a town in the Orange Free State, to a family that can be considered of middle-class background, being relatively wealthy farmers. The Orange Free state was one of the two Boer Republics, along with the Transvaal or Zuid-Afrikaanse Republiek (ZAR). These two republics were the result of the Afrikaners going their own way after many disagreements with their British overlords in the Cape area, which resulted in the Great Trek (1836-1838), in which about 10.000 Afrikaners migrated into the African interior.

These two republics would soon find themselves the target of British imperialism once again. One of the largest sources of gold in the world was found in the Transvaal in 1887, which made it a prime target for the British. The Boers, led by the legendary Paul Kruger in the Transvaal, were unwilling to give up their independence without a fight. And so, the second Anglo-Boer war started in 1899 (the first one being a somewhat minor battle in 1879, which the Boers won).

The war, which was lost by the Boers in the end (1899-1901), was a watershed moment in South African history. The cost for Britain was immense; it is estimated that about 450.000 soldiers were at some point in South Africa, almost double the entire population of the Boer Republics. Against such overwhelming odds, the Boers did the only thing they could; guerilla warfare, hit-and-run tactics, and a slow retreat into their hinterlands. They were put on their knees by the first use of concentration camps in history, which the British used to herd together the women and children of the fighting men. 27.000 people, mostly women and children, died there, and to me is probably the biggest atrocity the British ever committed in history, though the numbers are relatively low compared to other wars/famines.

Van Rensburg's first memories were of that war. Seeing the different soldiers in town and on their farm, first the Boers, and later the British. His grandfather and father had made a controversial decision for one living in the Free State; they did not go on commando with the Boer army, and were cordial with the invading British. They were not believers in the independent republican cause of the two Boer Republics, which was a position diametrically opposed to Van Rensburg's own thinking on the matter later on in his life.

The 1914 rebellion

The years 1902-1910 were a time of figuring out how to go on in South Africa. It was partly a time of rebuilding much that was destroyed in the Republics. Also, British politics were up to the question of how the new state would look and function. In the end, they settled on the Union of South Africa, with the borders that it still has today. The South African Party (SAP), led by Boer Generals Louis Botha and Jan Smuts, were tasked with trying to heal the wounds between English-speaking and Afrikaans-speaking white South Africans in the country.

International geopolitics would throw a wrench into this slow process, however. Britain saw itself threatened since 1870 by the then newly-formed German Empire, which threatened their European dominance. The complex web of alliances in Europe led to a chain-reaction in 1914, in which Britain would find itself at war with the Germans.

The German Empire held several African colonies at the time, one of them being German South-West Africa (today called Namibia). The British gave a simple task to the Union of South Africa in 1914: use the army to take and occupy South-West Africa for the Entente.

What they did not (care to) consider, was the response of the Afrikaners to this request. Only 12 years after the ending of a devastating war, in which about one-sixth of the Boer peoples died, they were now forced to fight for the power that fought them? This quickly devolved into a rebellion in the ex-Boer republics, led by the same Boer generals that had led them before, primarily Christiaan de Wet.

As mentioned, Van Rensburgs family was more British-oriented, and it showed once again during the developments of the 1914-rebellion. This time, his father Josh (remarkable name for an Afrikaner) went on commando, but with the South African army instead of the rebels. And he took his then 16-year-old son Hans with him for about half a year.

It would be a traumatic experience for the young Hans; seeing his people shoot each other in several battles, and seeing the corpses, some of whom he knew well, after the battles were over. It would instill in him the distinct necessity of Afrikaner unity, and not to be used by other powers against each other, which is what had happened during this rebellion.

Conclusion, for now

The rebellion, compared to the Boer War, was a small one, and was defeated. But it was a sign that Afrikaner resistance to the British was very apparent, both on the battlefield and in party-politics, where the newly-founded National Party was making waves, led by its leader, ex Boer general James Hertzog. Van Rensburg was still in the South-African equivalent of high school at the time, but his mind was already geared towards being of value to the Afrikaner cause.

This article will become way, way too long if I put the entire story into one article, so I will split it into several parts. It will allow me to make the detours and explanations necessary to tell the whole story as it should be told. I hope to see you all in the next installment.

-Pieter Nijmeijer

(Top image, self-made photo of book cover)

Your content has been voted as a part of Encouragement program. Keep up the good work!

Use Ecency daily to boost your growth on platform!

Support Ecency

Vote for new Proposal

Delegate HP and earn more