Good day Hivers and Book Clubbers,

Three years ago I went on vacation to Croatia with some friends of mine. For me personally it was the first time in what is considered the Balkans. It's an area of Europe not very well known by Western-Europeans overall, partly because of the distance between the countries, partly because news from the Balkans isn't considered front-page news here. Western Europe seems much more orientated towards the Antlantic, i.e. North America.

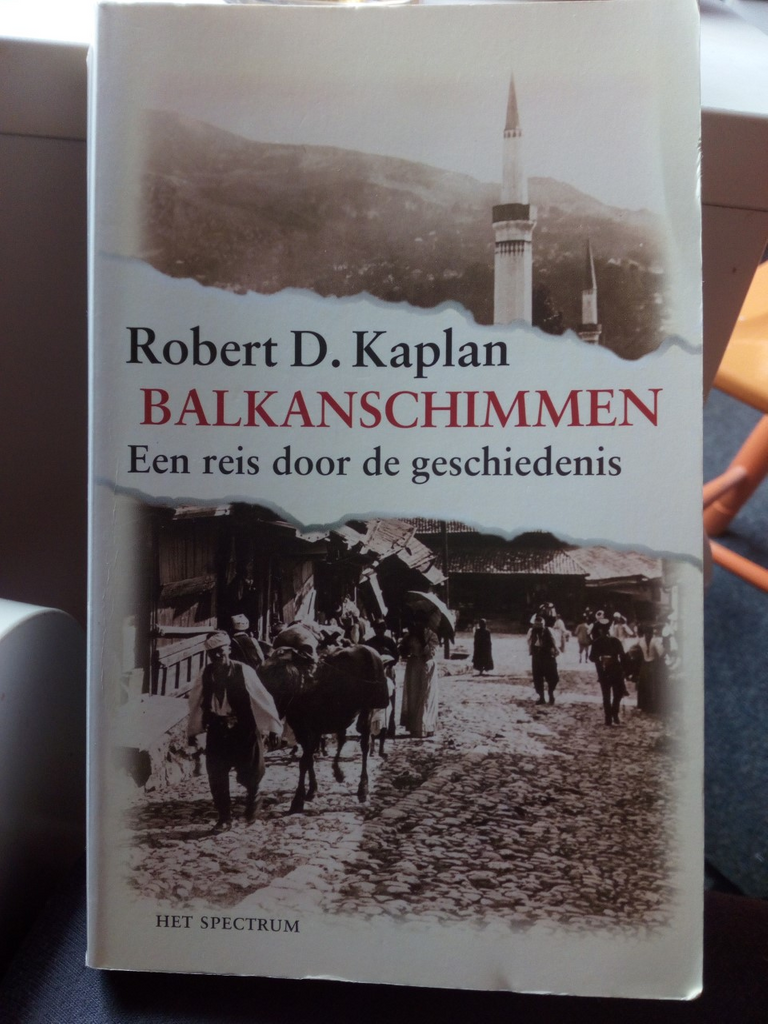

In short, this is what Robert D. Kaplan, a Jewish-American journalist and writer, found out for himself when he made many travels throughout the Balkans in the 1980s. He wrote many of his travels down in this book, titled in English 'Balkan Ghosts: A journey through history', first published in English in 1993. I got my hands on a Dutch copy, first printed in 1999. It numbers about 300 pages in total, so it's a decently-sized read.

Yugoslavia, or what's left of it

Kaplan's writings couldn't have been better timed, in a way: the world watched as the 45-year old experiment which was Yugoslavia imploded, due to both ethnic and religious tensions between several peoples and groups. However, Kaplan only dedicates 4 out of 17 chapters of his book to parts of Yugoslavia, and makes clear in a later-written foreword that his book was not intended as a 'crash-course in Yugoslav history'.

The historical background in these starting chapters are very relevant to the chaos and war that would commence in the 1990s. Yugoslavia was an odd creation from the beginning: after being occupied by Germany in WW2, the Partizans led by Josip Broz Tito grabbed power after the German loss in 1945. Tito kept the ship afloat for 35 years, until his death in 1980. Things quickly unraveled from there due to ethnic and religious tensions, and a severe lack of a strongman that was able to keep it all together nonetheless (something that Tito was able to do).

Kaplan first talks about the Croats, along with the Slovenes the only Catholic people in ex-Yugoslavia. This put them at odds with their historical rival within Yugoslavia: the Serbs. The Croats were very sympathetic to Germany in WW2, and thus were rewarded their own independent state at the time. This imploded when the Germans left, but the moniker 'fascist' was still often heard against them due to the collaboration of the Ustase.

The Serbs, a very old European people, were in a very complex position within (and without) Yugoslavia: though numerically the strongest, Tito (part Slovene, part Croat) often preferred to use a 'divide and conquer' tactic against the serbs, using other groups to prevent the Serbs from becoming the dominant group within Yugoslavia. The region where this became most painfully apparent is the region named 'Old-Serbia' by the Serbs, though most of the world knows it by the name 'Kosovo'.

Kosovo, recognised by about half of all the nations in the world, is mostly ethnically Albanian, and Albania has sought to annex it for decades. There is a minority of Serbs still there, however, and it is also of great symbolic importance to the Serbs due to the great battle they fought there against the Ottoman Turks in 1389... and lost. I find it pretty remarkable that such a definitive loss is still remembered vividly by a people. Its remembrance day is more a recognition of the suffering and loss, than most national holidays, which are often more positive.

Another odd dossier is North-Macedonia, still simply called Macedonia in the book. The book talks about the name-issue, which had become very relevant again last year, when the name of Macedonia was renamed North-Macedonia because of a long-standing historical dispute with the Greeks. The region that is now the independent country of North-Macedonia has been in many spheres of influence over the centuries: Greeks, Turks, Serbs, Albanians and Bulgarians all covet(ed) pieces or the entirety of the country in some form. However, in the second half of the 20th century, many Macedonians were wary of all these powers, and Macedonian nationalism became a force in itself, and successfully separated as an independent state from Yugoslavia.

Conclusion

The other three quarters of the book are dedicated to Romania, Bulgaria and Greece respectively. In this, Kaplan argues for their inclusion in the Balkan-story: they were all occupied by the Turks for long stretches of time, and took different routes from there: where Romania and Bulgaria fell under Soviet-Russian influence after WW2, Greece became part of NATO. Kaplan had lived in Greece for seven years at the time, and the Greek part is more of a review of Greek politics at the time than stories about his travels.

I have left out the more personal side of Kaplan's travels: who he met, which cities he travelled to precisely, and his thoughts of the social situations and poverty he saw while travelling and staying at these places. The book is very ambitious in its scope: to tell the histories of several countries, intertwined with his travels to places relevant to these stories. He succeeds for a large part, though he necessarily has to leave some big holes to get to the next subject. It's left to the reader to pick up the pieces, and to figure out for themselves what they would like to know more about.

I hope I've piqued your interest for this book, and to immerse yourself somewhat into the complex history of the many peoples that inhabit the Balkans. If you have any specific questions/additions, or live in any of the countries mentioned and want to weigh in, feel free to do so. I'm looking to do more reviews in the future, mostly in the non-fiction sphere, I'll see you all in the next one,

-Pieternijmeijer

(Top image: my own)

Nice review!!

!BEER

You need to stake more BEER (24 staked BEER allows you to call BEER one time per day)