I remember it like it was yesterday, but it was October 2011, when advertising posters on the sides of buses in Rome announced the exhibition on socialist realism at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, showcasing great Russian painting from the Bolshevik Revolution until the 1970s. I went, bringing my children, who were still in school. I suggested the idea to them, and they happily accepted. We hurriedly climbed the white steps of the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, eager to see the large canvases of the revolutionary painters.

We eagerly absorbed those images and colors that filled our eyes. Each of us, with our own sensitivity, focused on a canvas that captured our attention. The kids were so pleased that they talked about it in class with their teachers. For me, it was a rare opportunity to visit a well-organized major exhibition with works by great painters. I was fascinated by the powerful painting and the idealistic fervor emanating from those works. Years later, I remember it and today, I will speak briefly and necessarily incompletely about it.

When the Bolsheviks seized power with the coup of October 25, 1917, it was immediately clear that art in all its expressions would play an important role in advancing revolutionary ideas by proposing a new aesthetic-philosophical program. Among the arts, painting led the way. The artistic renewal broke with the past under the impetus of Lenin, who called for

"art comprehensible to the masses."

From the start, there was a debate about who would best interpret the Soviet program, which was beneficial because it led to a pluralistic artistic movement. Although focused on celebrating progress in industrial, technological, scientific, social, and cultural fields, it did not shy away from expressing its own stylistic and expressive content.

One of the leading theorists of artistic renewal was Anatolij Lunačarskij, a revolutionary and writer, who argued that art should stimulate the improvement of human life with images of physically robust, harmonious men and women with smiling faces and intense colors, depicted while engaging in sports, working in the fields or factories. The new art of the future had to be realistic, with a strong idealistic impetus. For fifty years, it was called Socialist Realism.

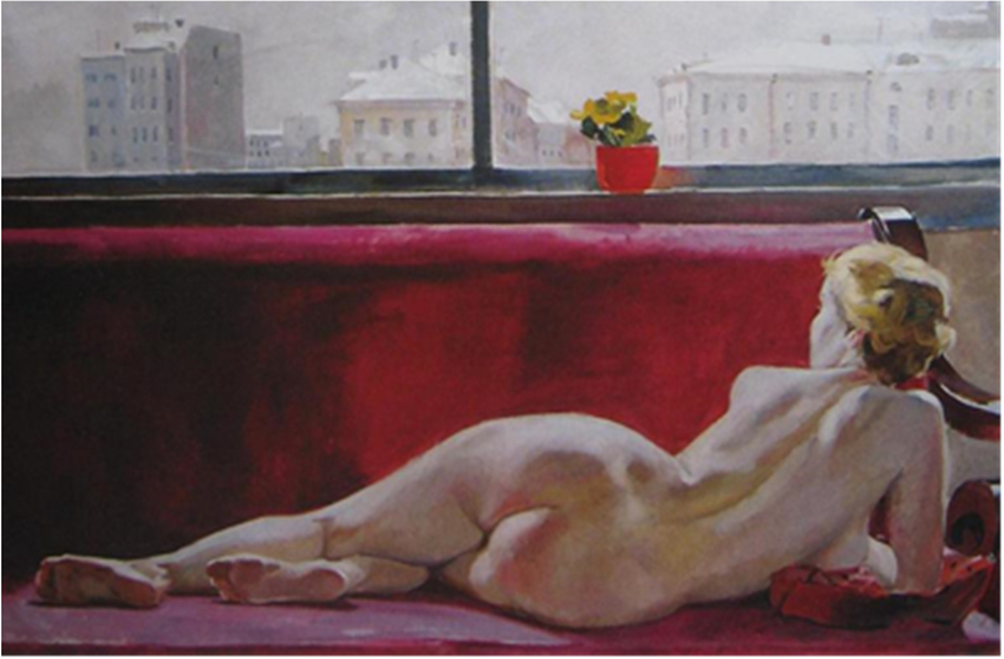

Among the artists featured in the exhibition, one particularly captured attention: Aleksandr Deineka (1899-1969). He was a painter, graphic artist, sculptor, and teacher and is considered by leading 20th-century critics to be the most important artist of Socialist Realism.

Deineka's art was not just propaganda; rather, it was a continuous effort to perfect formal and aesthetic content, experimenting with new techniques through rigorous drawing, graphics, photography, and cinema.

His paintings speak to us about life where it manifests: in sports, in the factory, in the fields, in war, through the representation of men and women aware and proud of the socialist ideal they are realizing. They are healthy and beautiful, smiling and happy, heroic and modern. In one of his writings, he stated what became the constant quest of his life:

“Art is somewhat of an ideal, the desire for a little more than what is seen, and a little better than what is lived.” Aleksandr Deineka

sources:

https://taccuinodicasabella.blogspot.com/2012/01/realismi-socialisti-grande-pittura.html

https://ilmondodimaryantony.blogspot.com/2019/10/aleksandr-aleksandrovich-deineka-1899.html

https://historia-arte.com/obras/carrera

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Aleksandr-Deineka-The-Model-1936_fig5_363928729

Ricordo come fosse ieri, ma era l’ottobre del 2011, quando cartelli pubblicitari posti sulle fiancate degli autobus di Roma annunciavano, al Palazzo delle Esposizioni, la mostra sui realismi socialisti, la grande pittura russa negli anni della rivoluzione bolscevica fino agli anni ’70. Ci andai portandomi i miei figli, ancora alle prese con la scuola dell’obbligo. Gli avevo proposto l’idea, che accettarono volentieri. Salimmo quasi di corsa la bianca scalinata del Palazzo delle Esposizioni, impazienti di vedere quelle grandi tele dei pittori rivoluzionari.

Con avidità rubammo quelle immagini e quei colori che riempivano gli occhi. Ognuno con la propria sensibilità privilegiò una tela che aveva rapito l’attenzione. I ragazzi furono talmente contenti che ne parlarono in classe con gli insegnanti. Per me un’occasione rara da cogliere, per poter visitare una grande mostra, ben realizzata con opere di grandi pittori. Fui affascinato da quella forte potenza pittorica e dallo slancio ideale che emanavano quelle opere. A distanza di anni la ricordo e oggi, ve ne parlo in modo fugace e necessariamente incompleto.

Quando con il colpo di stato del 25 ottobre del ‘17, i bolscevichi presero il potere, fu subito chiaro che un ruolo importate lo avrebbe dovuto svolgere, per far avanzare le idee della rivoluzione, l’arte in tutte le sue espressività, proponendo un nuovo programma estetico-filosofico. Tra le arti, la pittura fece da guida. Il rinnovamento artistico, rompeva con il passato sotto l’impulso dato da Lenin che invitava a fare

“un'arte comprensibile per le masse”.

Fin da subito vi fu una disputa tra chi avrebbe interpretato al meglio il programma dei soviet e questo fu un bene, perché diede corso a un movimento artistico plurale che se pur improntato ad esaltare i progressi nel campo industriale, tecnologico, scientifico, sociale e culturale, non rinunciò ha esprimere propri contenuti stilistici ed espressivi.

Tra i maggiori teorici del rinnovamento artistico vi fu Anatolij Lunačarskij, rivoluzionario e scrittore, il quale sosteneva che l’arte doveva stimolare il miglioramento della vita umana con immagini di uomini e donne dal fisico prestante, armonioso, con volti sorridenti e avvolti da colori intensi, dipinti mentre fanno sport, al lavoro nei campi o in fabbrica. L’arte nuova, del futuro, doveva essere realista, con un forte slancio ideale, per cinquanta anni si chiamò Realismo socialista.

Tra gli artisti presenti alla mostra, uno in particolare rubò l’attenzione, fu Aleksandr Deineka (1899-1969). È stato pittore, grafico, scultore e insegnante e oggi viene considerato, dai maggiori critici del novecento, il più importante artista del Realismo Socialista.

Non fu solo propaganda l’arte di Dejneka, al contrario, fu un lavoro continuo di perfezione dei contenuti formali ed estetici, sperimentando nuove tecniche attraverso il disegno rigoroso, la grafica, la fotografia e il cinema.

I suoi dipinti ci parlano della vita là dove si manifesta, nello sport, nella fabbrica, nei campi, nella guerra, attraverso la rappresentazione di uomini e donne consapevoli e fieri dell’ideale socialista che stanno realizzando. Sono sani e belli, sorridenti e felici, eroici e moderni. In un suo scritto affermò ciò che divenne la costante ricerca della sua vita:

“L’arte è un po’ l’ideale, il desiderio di un poco di più di ciò che si vede, e di un po’ meglio di ciò che si vive”. Aleksandr Deineka

Fonti:

https://taccuinodicasabella.blogspot.com/2012/01/realismi-socialisti-grande-pittura.html

https://ilmondodimaryantony.blogspot.com/2019/10/aleksandr-aleksandrovich-deineka-1899.html

https://historia-arte.com/obras/carrera

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Aleksandr-Deineka-The-Model-1936_fig5_363928729

Congratulations @marcelloracconti! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 3750 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP!discovery 35

Grazie! di essere passato a condividere

This post was shared and voted inside the discord by the curators team of discovery-it

Join our Community and follow our Curation Trail

Discovery-it is also a Witness, vote for us here

Delegate to us for passive income. Check our 80% fee-back Program

Veramente interessante! Un occhio critico e veritiero sulla società dell'epoca...

Grazie per la condivisione :)