You know Gregor Mendel right?

He's the priest who is ubiquitous in basic biology courses and commonly touted as the father of genetics (De Castro, 2016). Mendel was experimenting with the idea of his day that the traits of offspring appeared from some sort of dilution of its parents. He started with mice, but this was frowned upon by his bishop because it required studying sexuality in animals and the bishop didn't think this was something that a monk should do (Raudenska et al., 2023) He ended up working on the hybridization of pea plants, and created the laws of inheritance.

Gregor Mendel's hybridization experiment involved cross-breeding thousands of pea plants with different traits, such as tall and short or different colored peas, and observing the inheritance patterns of these traits across multiple generations (Mendel, 1866). He was a pioneer for his time using data to drive the hypotheses, not a gut feeling (Raudenska et al., 2023) Most importantly, he showed that the variation was not magic. It was predictable. They should have been screaming his name from the rooftops in his day.

Did they not celebrate because Mendel was such a peculiar fellow?

He was a monk, but found to not be suited to be a monk as he was too timid (De Castro, 2016). It was said that he was particularly good in his scientific studies, and that maybe he should focus on that, but he couldn't really make the cut in academia either as he failed his teaching certification twice. Mendel seemed to elude the credibility that checked all of the standard boxes. However, it is probably most likely that in his time no one cared or at the very best didn't understand the implications of his work. There were very few citations on his work in the years after. It wasn't until decades later that many noticed his work, and even then it was heavily scrutinized.

Maybe Mendel just needed some fruit flies.

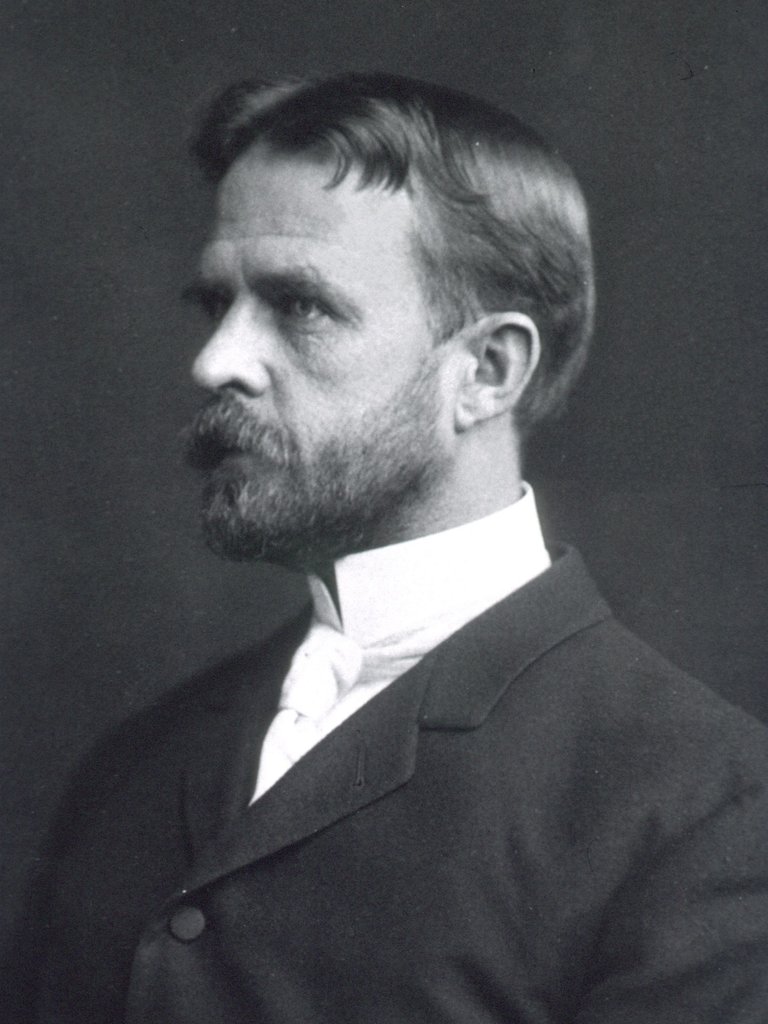

Photo of Thomas Hunt Morgan - By Unknown author - http://wwwihm.nlm.nih.gov/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=549067

Drosophila melanogaster wasn't the first choice of Thomas Hunt Morgan (professor of zoology at Columbia University)(Weiner, 2000). Morgan was a miser and lacked the space needed for a bigger organism. Morgan told his student to place some bananas in the window, and to catch some flies for experimentation. If this seems "cheap" to you, you'd probably find it more alarming that they housed the flies in stolen milk bottles. They were going to try to experiment with behavior, especially regarding drosophila's natural inclination to head toward light for the student's class project. After many generations they produced an underwhelming fly that "more slowly" moved toward the light.

Morgan and his students wanted to see some real definitive changes. They just started throwing things at the wall. They tried variations in temperature, using X-ray, and even injected acids/bases/salts/sugar/alcohol into the private parts of flies. There was little sophistication in their methodologies, but eventually they found something. When they focused on changing a specific piece of drosophila's anatomy through selective breeding, namely something that looks like a trident on the fly's thorax, they finally found one fly with white eyes. If that seems random to you, it's because it is. Everything in biology seems to indicate that things happen by chance. This was no exception. After two long years of ambiguity, they had a "feeble" white-eyed mutant.

Even though it was mission-accomplished for Morgan and his students, there was still the question of, "Why does this happen?" Also, it seemed to happen in males more often. Morgan remembered an obscure paper that he read written by a relatively unknown monk by the name of Gregor Mendel. He remembered what we now know about recessive traits and wondered if white eyes could be a recessive trait in flies. He observed an inheritance pattern that was sex-linked (Morgan, 1910). Males, only having one x chromosome would exhibit a more probabilistic chance to express a trait linked to the x chromosome that they received from their mother. Females have two x chromosomes, meaning they would have to have the white-eyed trait from their father and mother to exhibit the trait. Through records kept on breeding and the traits observed in offspring, they could float a hypothesis out there that inheritance wasn't magic, but a direct result of receiving information through chromosomes.

Morgan mentions that his idea of a gene was contested (Morgan 1917). He states:

"The objections have taken various forms. It has been

said, for instance, that the factorial interpretation is not

physiological but only "static," whereas all really scientific explanations are "dynamic." It has been said that since the hypothesis does not deal with known chemical substances, it has no future before it, that it is merely a kind of symbolism. It has been said that it is not a real scientific hypothesis for it merely restates its facts as factors, and then by juggling with numbers pretends that it has explained something. It has, been said that the organism is a Whole [sic] and that to treat it. as made up of little pieces is to miss the entire problem of "'Organization.'" It has been seriously argued that Mendelian phenomena are "unnatural," and that they have nothing to do with the normal process of heredity in evolution as exhibited by the bones of defunct mammals.' It has. been said that the hypothesis rests on discontinuous variation of characters, which does not exist. It is objected that the hypothesis assumes that genetic factors, are fixed and stable in the same sense that atoms are stable, and that even a slight familiarity with living things shows that no such hard and fast lines exist in the organic world. These and other things have been said about the attempts that the students of Mendel's law have made to work out their

problems."

Wow, that's a lot to take in. I love that it mentioned an argument that essentially says "bUt We'Re NoT mAdE oF aToMs." It just goes to show you that we need to take a step back in science every once in a while and evaluate the information. But I digress.

Photo of Gregor Mendel - By Unknown author - Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33347279

Unlike Mendel, Morgan's name was eventually shouted from the rooftops. He won the Nobel prize in medicine in 1933 for his work that showed chromosomes were linked to inheritance. Was the pea plant too benign for such accolades? Was Mendel viewed as too much of a failure by his peers? Did Mendel just need some flies?

Maybe it's secondary to the innate doubt built in every scientist, as Richard Feynman (1999) so eloquently put it:

“The scientist has a lot of experience with ignorance and doubt and uncertainty, and this experience is of very great importance, I think. When a scientist doesn’t know the answer to a problem, he is ignorant. When he has a hunch as to what the result is, he is uncertain. And when he is pretty damn sure of what the result is going to be, he is still in some doubt. We have found it of paramount importance that in order to progress, we must recognize our ignorance and leave room for doubt. Scientific knowledge is a body of statements of varying degrees of certainty — some most unsure, some nearly sure, but none absolutely certain. Now, we scientists are used to this, and we take it for granted that it is perfectly consistent to be unsure, that it is possible to live and not know. But I don’t know whether everyone realizes this is true. Our freedom to doubt was born out of a struggle against authority in the early days of science. It was a very deep and strong struggle: permit us to question — to doubt — to not be sure. I think that it is important that we do not forget this struggle and thus perhaps lose what we have gained.”

Would you have ever expected the revelation of inheritance to be born of a fruit fly caught in the window sill using bananas as bait? *It seems like flies might be important."

(Also, @coloneljethro isn't it crazy this dude was born and raised in Lexington, Kentucky? How come they never let us know about that in school?)

References:

De Castro M. (2016). Johann Gregor Mendel: paragon of experimental science. Molecular genetics & genomic medicine, 4(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.199

Feynman, R. P. (1999). The Pleasure of Finding Things Out: The Best Short Works of Richard P. Feynman. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books.

Mendel, Gregor. 1866. Versuche über Plflanzenhybriden. Verhandlungen des naturforschenden Vereines in Brünn, Bd. IV für das Jahr

1865, Abhandlungen, 3–47.

Morgan, Thomas Hunt. "Sex limited inheritance in Drosophila." Science 32.812 (1910): 120-122.

Morgan, T. H. (1917). The theory of the gene. The American Naturalist, 51(609), 513-544.

Raudenska, M., Vicar, T., Gumulec, J. et al. Johann Gregor Mendel: the victory of statistics over human imagination. Eur J Hum Genet 31, 744–748 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-023-01303-1

Weiner, J. (2000). Time, love, memory: a great biologist and his quest for the origins of behavior. Vintage.

Ah, so he's from that bunch of Morgans. Did learn about his Confederate general uncle but that was because I was a big Civil War buff growing up but they sure neglected to mention Thomas. Curiouser and curiouser.

On the genetics front, are you familiar with Lysenkoism?

I didn't realize there was a that bunch. I did read he was a "Kentucky aristocrat." Funny how we can learn about confederate generals, but not the dude who wins the Nobel Prize for genetics. Nice.

And not until just now for the Lysenkoism. Wow. I'm going to have to do some digging on it, but seems pretty messed up.

Glad I tagged you man! You learn something new everyday.

Yeah, I think his grandfather was the first millionaire this side of the mountains. Kentucky was a smaller place back then and there were a few families that kind of dominated politics/business and the Morgans were one of them.

It's quite messed up, and a nice case study in what happens when politics dictates science. Also curiously obscure.

Glad you did too, it's always good to hear from someone in this neck of the woods.

Thank you for sharing.

Thanks for your contribution to the STEMsocial community. Feel free to join us on discord to get to know the rest of us!

Please consider delegating to the @stemsocial account (85% of the curation rewards are returned).

You may also include @stemsocial as a beneficiary of the rewards of this post to get a stronger support.

Maybe they just weren't willing to take him seriously despite his being right, because his first choice was to be a monk?

This post has been manually curated by the VYB curation project

That could be, but it's hard to say in his time. I do know that there were many arguments brought up years later that he was falsifying evidence because he wouldn't agree with evolution because he was a monk. However, the timeline says otherwise. It's very unlikely that he knew anything about Darwin.

There were many scientists, especially at that time, who were religious. In fact some of them were some of the more famous scientists in history.

Thanks for the curation!

Do you have any information about VYB that I can read about?

It makes sense that religious people should pursue careers in academia. The Bible does challenge believers to study the natural world.

My pleasure :) VYB is a curation project founded by @calumam - all curators still hold both vyb and pob delegations, but the rest of it is currently on hold, as he is currently offline.

Congratulations @kryptik! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 20000 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP