FIAT MONEY AND ITS CONSEQUENCES FOR CAPITALISM

!( )

)

(Image from Pinterest.com)

INTRODUCTION

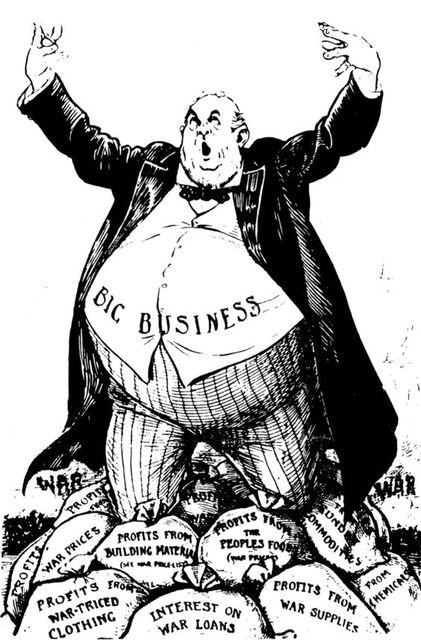

Take a look at these two images. What do they show?

!( )

)

(Image from commons.wikimedia)

!( )

)

(Image from monopoly.wikia)

Obviously, the answer is that they are pictures of real money and fake money, toy money, pretend money. But just what is it about a particular slip of paper or metal token (and not any old slip of paper or metal token) that makes it ‘real money’?

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MONEY

Before getting into that, it might be worth having a quick look at money’s history. What we use as money originated in Venice in the thirteenth century. Back then, people used gold coins as money. As you can imagine, walking around with gold in their pockets made folk vulnerable to theft and the goldsmiths saw a business opportunity in that unfortunate fact. They could charge customers a fee for keeping their gold safely locked away in the vaults. The townsfolk agreed that this was a good idea, handed over their gold along with the fee, and were issued with receipts that could be later exchanged in return for their gold.

The townsfolk then adopted the attitude that those receipts were as good as real money, which is to say they were generally regarded to have or represent value, and were acceptable as a medium of exchange. Indeed, in one way they were more convenient, in that it was much easier to carry around slips of paper rather than gold coins. And so tradesfolk accepted those receipts in payment for goods and services.

MAKING MONEY OUT OF NOTHING

!( )

)

(Image from pando.com)

As time went by, the goldsmiths noticed that the townsfolk preferred to use those slips of paper as 'money'. The more astute goldsmiths also noticed that when their customers did withdraw their gold, they rarely withdrew it all at once. Instead, they preferred to withdraw just a part of the total deposit and leave the rest where it was. So, the goldsmiths figured they could get away with issuing loans in excess of the gold that was in the vaults. Customers came along, receiving receipts they assumed were 'real money' ie represented a certain amount of gold. In reality, that gold did not exist.

The idea of selling somebody something you do not have sounds like fraud. Remember, though, that the goldsmiths did have some gold, just not enough to back all the paper money they were issuing. Since their customers rarely demanded all their gold, their scheme worked so long as debt repayments provided sufficient reserves to meet those needs. On the other hand, if word got around that a lot of that paper money was essentially worthless (since it was really backed by nothing) there would have been a rush to withdraw what gold there was before somebody else got to it. As for the act of issuing loans rather than buying and selling gold, it meant the customer was no longer dealing with a goldsmith but rather a bank, an organization whose main source of income comes from other other people's debt. Issuing loans is not intrinsically bad. There are times when it is very useful to borrow money. But when you are profiteering from debt there is a temptation to increase it as much as possible, since the more debt there is the richer you get.

The rest of the goldsmiths' story is a rather familiar one of great wealth made and reputations lost; of rules and regulations established and subsequently eroded as the lure of riches overrode common sense. And the reason why it is familiar is because the practice of making money out of debt now forms the very basis of the modern monetary system.

FIAT MONEY

When a person, business or country borrows money, they are not given money that somebody else deposited or that the bank has in its vault. Instead, if a person wants to borrow, say, £10,000, the bank types £10,000 into that person's account and, hey presto, there it is. This kind of money is called 'Fiat money' after a phrase in the Latin version of the Bible, 'Fiat Lux' or 'let light be'. The reference is obvious: Banks have the ability (or rather, the authority) to make money out of nothing (strictly speaking they are making money out of debt ).

Eventually, that newly created £10,000 will end up being deposited in another bank account. When that happens, that bank is obliged to hold ten percent of that deposit in reserve and is entitled to issue the other ninety percent as new loans. However, that ninety percent does not come out of the original deposit. Instead, it is £9,000 created on top of the original $10,000. This process repeats every time money is deposited in an account. Thus, the supply of credit money is expanded. This process is known as 'Fractional Reserve Banking'.

HOW IS PAPER WORTH ANYTHING?

What gives fiat money value? One answer is: The money that already exists. The new money steals value from the money already in circulation. When the money supply is expanded irrespective of demand for goods and services, that upsets the equilibrium of supply and demand and diminishes the buying power of each pound, dollar or whatever. This devaluing of the currency manifests itself in higher prices for goods and services. In other words, you get inflation. Today one would need $405 to purchase goods that cost $100 in 1975. Now, wealth cannot be destroyed only redistributed, so if some are finding their wealth is disappearing, it must be going somewhere. And where it is going is into the pockets of that part of society that has positioned itself to take advantage of the fiat money system. Officially, the role of central banks is to bring some stability to financial markets and banking, acting as 'lender of last resort' in order to save critical industry's from bankruptcy and therefore avoid disastrous depressions. However, some claim that central banks and the system they are part of have another agenda. Ruling bodies- monarchies, governments-get their wealth through taxes but this form of rent can only be raised so far before the masses revolt. It is claimed by some that the central bank's ability to print money out of nothing and therefore have great control over the rate of inflation, amounts to a hidden form of taxation that can extract wealth from the masses without them catching on to this loss.

You may have noticed that we have so far provided only a partial answer to the question of where fiat money gets its value from. After all, if the new money gets value by stealing it from the money that already exists, where does that money get its value from? The answer to that question can be found in the definition of 'real money' in a fiat money system.

THIS IS WHAT MAKES FIAT MONEY 'REAL'.

!( )

)

(Image from peterkuper.com)

If you have ever played Monopoly, chances are that somebody held up a pretend banknote and said, "imagine if this was real money!". But have you ever wondered why it is not? Well, first of all it is the law that fiat money is money, meaning that unless such money can be shown not to have come from the legitimate source (IE whoever has legal authority to print it) anybody selling anything must accept such money as payment. Thus, such money overcomes the greatest difficulty of any currency, which is not its creation but rather getting enough people to accept it in exchange for commodities.

But there is another, even more important reason why Monopoly money is not ‘real’: you cannot pay taxes with it. Why do we pay taxes? Not really for the reasons most often given. We are told taxes are essential if we are to have services such as road maintenance, schooling, or garbage disposal. But that is not true because even if we did not pay taxes all such services could still be provided. This is because there is a demand for them, and wherever there is demand market economies adapt to meet it. That is just good business sense. And it does not require so-called 'real money' in order to make this happen, because just about anything can serve as a medium of exchange and unit of currency provided it is portable, durable, divisible and fungible. Monopoly money could be one such item.

But you cannot pay taxes with anything other than what the law says is to be used for that purpose. And since you are required to pay taxes, you are therefore obliged to procure that which is used for this purpose. So the real purpose of taxes is to give value to whatever government decrees to be 'real money' and the definition of 'real money' in a fiat money system is, yes, 'that which is used to pay taxes'.

WHAT FIAT MONEY REALLY REPRESENTS

The fact that this is what 'real money' is under the current system, coupled with the way the fractional reserve system creates money out of debt through the issuance of loans, has implications for what money represents. The common assumption is that money equals wealth. It is not hard to see why: The more money you have, the richer you are. But, the money creation process commences with government defining what is money by saying what is to be used to pay taxes. Since we never stop paying taxes we always owe money to the government, which is to say, we are always in debt. Furthermore, the way the fractional reserve system works inherently creates more debt. In fact, today ninety seven percent of all money is created as debt. So, in a fiat money fractional reserve system, money equals debt. It may be the case that the more money you have the richer you are, but it is also the case that the more money there is the more debt there is.

INTEREST

Whenever money is borrowed, it typically has to be paid back plus accrued interest. For example, if I borrow £10,000, at 9% interest I must pay back £10,900. Now, the banking system only creates enough money to pay back the principle (ie the original £10,000) not the interest. Therefore, the total amount of money in existence is insufficient to repay all loans plus interest.

This has lead some to conclude that our-debt-based, interest-bearing currencies must lead inevitably to growing debt. There simply is no way for all the money plus interest to be repaid, other than to borrow the extra amount. But that extra also has interest charged. Therefore, the more we borrow, the more we have to borrow, in a never-ending spiral of growing debt.

There is, however, a way to pay back more money than actually exists. To see how, we can turn to a simplified example. Imagine that Alice and Bob live alone on an island. Bob is in possession of a pound coin, the only money on the whole island. Alice asks to borrow the pound, and after interest is added she must pay back £5. How can she do that? She can submit to paid labour. She paints Bob’s fence, and earns £1 salary. She hands that £1 over and pays of a part of her debt. Next day she prunes Bob’s roses, and receives the same £1 she was paid as wages yesterday. Again, she hands it back as payment for part of her interest-bearing debt. This revolving-door process of money handed back and forth as wages and repayment can continue until the debt is paid off entirely.

The same principle can apply in the real world. Say a bank loans £10,000 at £900 per month and that £80 represents interest. That interest is spendable money in the account of the bank. The bank decides to hire a cleaner, and the result is not all that different from the simplified case. Nor do you have to literally seek employment at the very branch of bank which you borrowed money from. So long as there is no requirement to repay everything at once, so long as the money needed to pay interest is spent into the economy, and so long as there are wage-paying jobs, it is possible to repay debt plus interest even though the total amount of money is never enough to cover all the money owed.

Another popular idea, in marked contrast to the previous belief of absolute shortage, is the idea that since banks spend interest charges as operating expenses, interest to depositors and shareholder dividends, there is in fact enough money released back into the community to make all payments. But this is an oversimplification that rests on the assumption that interest-bearing money is always spent into the economy, never lent at interest or invested for gain. In reality, there are a significant proportion of non-bank lenders, and if they manage to capture some of the money needed to retire the loan that created that money, the original loan cannot be retired. Beyond that there is a cultural expectation that money should generate more money- not through productive effort but through mere investment for personal gain.

The theory that there is always enough money spent into the productive economy to pay off interest has to be true 100% of the time. But that cannot be the case when the money needed by borrowers in everyday productive economics is instead moved ‘upstairs’ to play in a casino world where players essentially gamble on how money moves through financial systems. For example, the volume of trade on the world’s foreign exchange markets in just one week exceeds the total volume of trade in real goods and services during an entire year. This money is in continuous play by speculators hoping to make windfall profits on currency fluctuations; it is money circulated for no reason and no productive outcome, other than to make more money. Nowhere in our system is there any restriction on re-lending money or investing it for personal gain in the casino economy that is, arguably, completely auxiliary to the real, productive economy. It stands to reason that every time interest is added to money that already bears an interest charge (as happens when secondary lenders capture such money) and every time money is taken out of circulation in the real, productive economy, that increases the pressure on the system to repay the debt.

Producers may respond by increasing sales or raising prices. Consumers may meet the demand by taking on an additional job or paying off debts over a longer period of time. Governments may respond by raising taxes. But each tactic comes with possible negative consequences. For producers, competition for sales usually entails lowering prices, a move that necessitates even more sales and possible overproduction and saturation of the market. Increasing taxes drains money from the productive economy, thereby reducing the collective ability to pay taxes, which then necessitates deficit spending and additional interest charges. Competition for jobs lowers wages, lower wages means less consumer spending, and paying interest over longer periods adds enormously to the amount of interest owed.

WHO BENEFITS?

!( )

)

(Image from commons.wikimedia)

The truth, regarding the affect that interest has on our lives, lies somewhere between those opposing extremes in which the money supply is believed to be in absolute shortage on one hand, and always available on the other. In principle, the money could be made available provided it were always spent into the real, productive economy, but it isn’t. And the result- fuelled in part by the commodification of debt and what some call the ‘money sequence of value’ (meaning systems that do nothing except turn money into more money)- is increasing debt, and people finding the struggle to keep themselves afloat becoming harder as the system plays out.

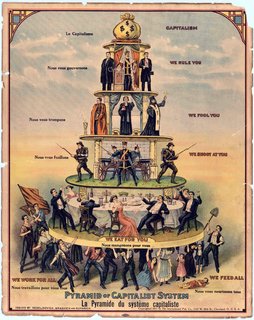

So who benefits from a crazy system like this which causes debt to grow and grow? Those who control the money, that’s who. Remember: banks profit primarily from interest-bearing debt. As G. Edward Griffin put it:

“No matter where you earn the money, its origin was a bank and its ultimate destination is a bank...this total of human effort is ultimately for the benefit of those who create fiat money".

In other words, the earlier you get the newly created money the more you benefit. Therefore, those who have the authority to issue money benefit the most: Governments and banks. Borrowers who get this money early- for instance large corporations and government contractors- are next in line of those who benefit. They can spend the money before inflation caused by the new money raises prices. Prices do rise due to inflation, so holders of assets such as houses or shares will see gains in the value of that asset without there necessarily being any real improvements made. As for those at the bottom of the pyramid- for example people on fixed wages or incomes- by the time the money trickles down to them, the prices of things they need to buy have increased. Since their wages remain largely unchanged and their savings now buy less, in some cases they have to take on debt just to be able to afford what they were previously able to buy. Which means, of course, going back to the banks. And so the rich-poor divide gets bigger and bigger. In practice, then, the debt-based fractional reserve system is one designed to redistribute wealth from the bottom of the financial pyramid to the top.

This conclusion was borne out by studies conducted by the monetary analyst Helmut Cruz. He found that there was an upward concentration of wealth from the bottom eighty percent to the top twenty percent, especially the top ten percent, and this transfer of wealth occurred independently of the cleverness or industriousness of the participants. It was, instead, due exclusively to the interest feature of the fiat monetary system.

Furthermore, Thomas Piketty argues that there is a fundamental inequality built into capitalism which can be expressed in the simple equation r>g. R stands for the average annual rate of return on capital- things such as profits, dividends, interest, rents- expressed as a percentage of its total value. G stands for the overall growth of the economy. IE the annual increase from income or output. According to Piketty, what this equation describes is a consequence of slowly growing economies. He wrote, "in slowly growing economies, past wealth naturally takes on disproportionate important, because it takes only a small flow of new savings to increase the stock of wealth steadily and substantially".

In other words, as some people, through a combination of entrepreneurship and luck, really win at the game of capitalism, they can become rentiers, living very well off of sources of income other than wages and profits. And, once one's income exceeds a certain amount, it becomes possible to purchase things which are really beyond affordability to most of us. For example, with one percent of the capital gained from interest, billionaires can hire the services of the world's top financial advisers and accountants, people with the greatest expertise in using every trick in the book to make money grow, not all of them moral. In fact, a recent study concluded that 35% of the world's top owners is due to providing goods and services in the real economy, and the rest comes from rent-seeking or methods of taking wealth away from the rest of us. Of course, most of us have nowhere near enough money to hire such expertise in managing wealth and increasing capital.

It is often said that no illegality is involved in the explosive growth of the .1%'s wealth, but that is not surprising when you consider that substantial amounts of money can be used to buy governments (not directly, perhaps, but through 'campaign contributions' and other indirect methods). Obviously, these tycoons expect something in return, and that something is a market that is rigged to favour their class over others. One might still argue that at least they contribute 35% of their wealth to creating jobs but eventually the assets they have built up and the rigged economy they have engineered gets passed down to new generations of rentiers who make no contribution at all. And, in accordance with r>g the inequality gap gets wider and wider irrespective of any meritocratic input, until democracy itself cannot continue and we are left, as G. Edward Robinson said, with "a form of modern serfdom in which the great mass of society works as indentured servants to a ruling class of financial nobility”.

Funny enough, I remember I think in economics class we learned about this one culture where they used these huge heavy sandstone discs for money. I think maybe so it would be harder to steal money. So I guess different money systems have their advantages and disadvantages. Some are better at solving certain challenges associated with money, whether it be liquidity, making it harder to steal, making it easier to carry, etc.