"With so much abundance, it very likely never occurred to most entomologists of the past that their multitudinous subjects might dwindle away. As they poured themselves into studies of the life cycles and taxonomies of the species that fascinated them, few thought to measure or record something as boring as their number."

-Brooke Jarvis, The Insect Apocalypse Is Here, November 27, 2018

Late last year, The New York Times published a long-form article, The Insect Apocalypse is Here, about the dramatic decline in global insect populations. After decades of under-studying the abundance of insects, we are realizing that their numbers are plummeting, with devastating potential consequences. As author Brooke Jarvis writes, “Insects are a case study in the invisible importance of the common.” Central to the piece, and the research illuminating the scale of the problem, are volunteer naturalists who have painstakingly collected and cataloged insects that professional science has frequently neglected or been unable to research. Researchers are now turning to their records and collections—sometimes centuries old and decades long—to retroactively document what we’ve lost. At the same time, a worldwide array of universities, museums, scientists, and volunteers are stepping up to gather insects and data.

"The long-term details about insect abundance, the kind that no one really thought existed, hadn’t appeared in a particularly prestigious journal and didn’t come from university-affiliated scientists, but from a small society of insect enthusiasts based in the modest German city Krefeld." - Brooke Jarvis

The secrets in historical collections, passionate “amateur” scientists, the relevance of science to humans’ everyday lives—these are all part of the world of the Wagner, too.

From May 2015 to March 2016, the Wagner conducted an insect diversity survey in our yard using a malaise trap. A malaise trap is a large, fine net with a bottle on one end. Insects fly into the trap’s wide opening, then continue to fly upwards, where the trap narrows and leads to a bottle of ethanol. The project was a collaboration between Greg Cowper of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University’s (ANSP) Entomology Department, Wagner staff, and volunteers. Greg has long used a malaise trap to record insect populations on the grounds of Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary. (Greg is also a member of the Wagner’s faculty and regularly teaches our free college-level entomology courses.) Wagner site manager Don Azuma suggested that Greg install a malaise trap in the Wagner’s yard as both a teaching tool and chance to expand his data.

In May 2015, Greg and ANSP entomology collection manager Jason Weintraub installed the trap in the Wagner’s yard. About every two weeks over the ten months that the trap was in use, Don and Wagner museum assistant Adam Knapp removed the trap’s harvest. Adam also worked the front desk at the Wagner. During quiet periods, he pre-sorted the insects by order (e.g. flies, butterflies) and, when possible, genus and species. Over the course of the project, Adam began volunteering in the ANSP’s entomology department, giving him access to more sophisticated tools.

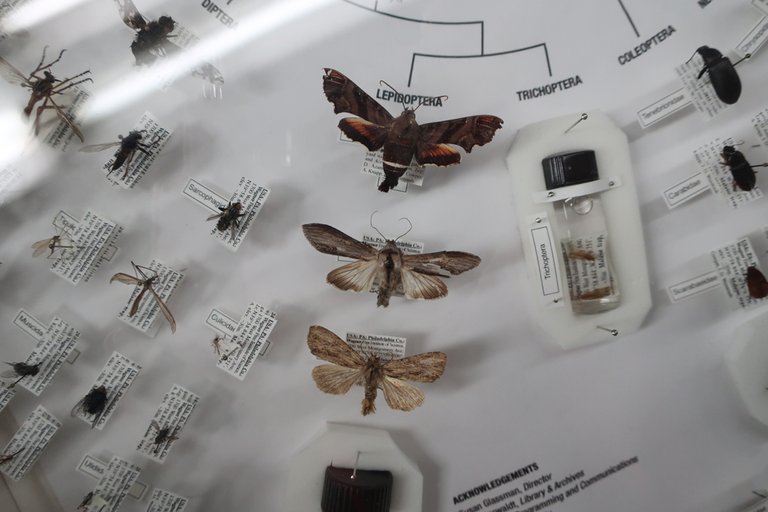

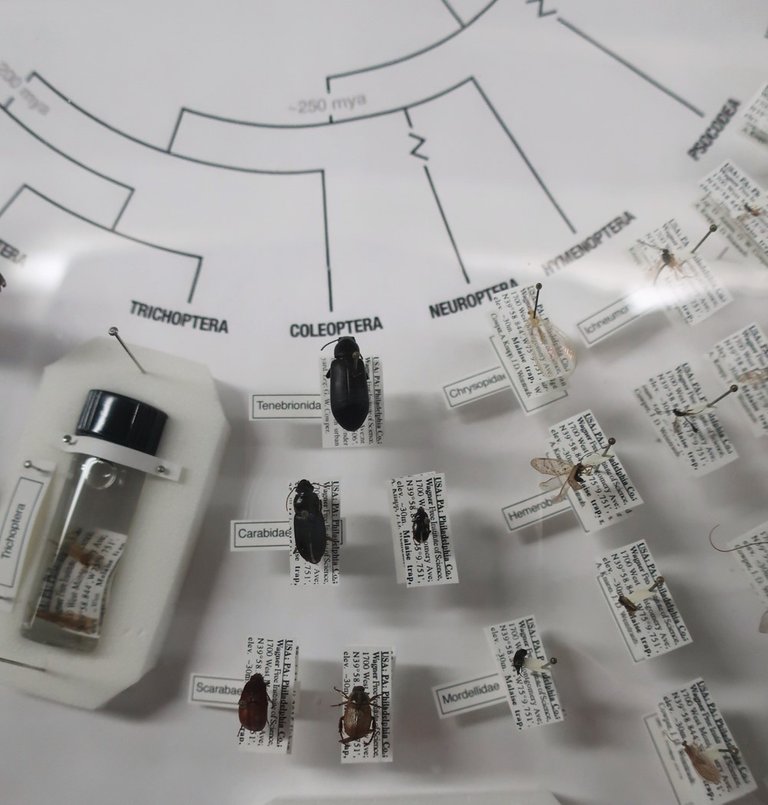

In the end, 1,250 insects were pinned and labeled and 150 vials of insects were preserved. Most of the insects are in the Academy of Natural Science’s entomology collection for future cataloging and research. A sampling of the collected insects joined the Wagner’s museum collection, painstakingly mounted in pins or preserved in small vials and labeled with their species. With the help of paleontologist Jason Downs, the insects are arranged phylogenetically in a circular “Tree of Life” depicting their evolutionary development and history. (Jason is also a Wagner faculty member!) The phylogenetic chart was partially informed by genetic data, technology not available to the creators of our historic collection. The drawer with this display sits in case 22B in the Wagner’s museum, next to and surrounded by 19th and early 20th-century insect displays. Besides the drawer’s rich detail of biological information, this juxtaposition provides additional insights.

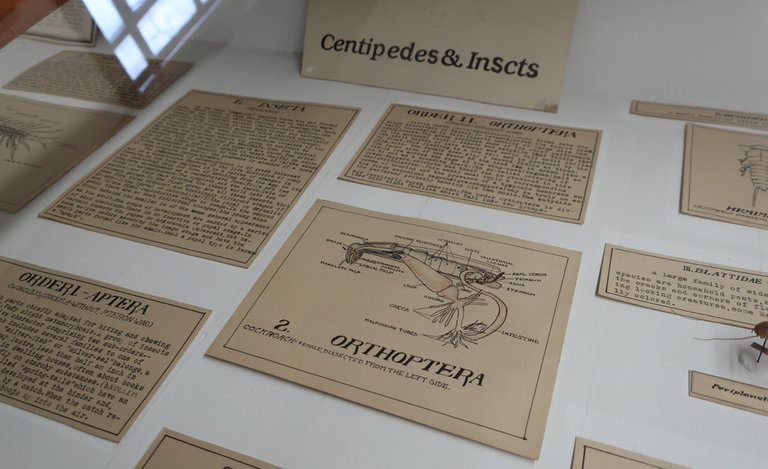

Most of the Wagner’s insects were collected and organized by Wagner curator Charles Willison Johnson. Johnson was an entomologist and malacologist who was curator of the Wagner from 1888 to 1903. Some of the Johnson cases are a dizzying mass of carefully sorted insects, their taxonomic label the only written guide. Others include explanations and illustrations of the notable features of the family or order. In some cases, the taxonomies have changed since the insects were labeled, turning the labels into artifacts of early 20th-century scientific knowledge.

Family Culicidae

Antennae thread-like composed of 15 joints; the 1st joint thick, the following small, round and beset with whorls of hair, forming in the male a long dense plumosity. Proboscis long. Wings long and narrow, the hind margin fringed, veins numerous. The larvae live in still water.

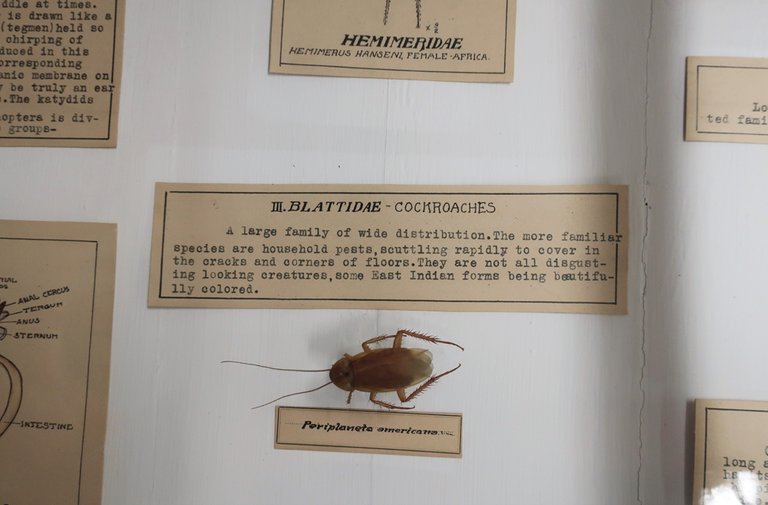

Like metamorphic rocks, the insect cases in Wagner’s synoptical collection have an additional layer of historical interpretation. The Wagner’s synoptical collection, begun during Johnson’s time as curator, was designed to show a sampling of nature’s diversity and the range of complexity in the animal kingdom. While the insects in the synoptical collection are Johnson’s, Wagner employee and curator John G. Hope re-labeled them in the 1930s/1940s. Like Johnson’s, Hope’s displays are organized taxonomically and include descriptive labels and detailed illustrations. Unlike Johnson, Hope added more ecological context, including subjective commentary about the beauty and merits of different insects.

VI ODONATA

Dragon flies. Conspicuous insects for their large size; slender elongated abdomen; movable head and large eyes. Wings situated back of the legs. Metamorphosis but no pupal stage; larvae an aquatic nymph. Predatory, voracious feeders destroying large numbers of insects, particularly mosquitoes capturing their prey on the wing by “hawking” methods. Known also as “mosquito hawks,” devil’s darning needles” and “horse stingers” and held in some awe by country folk. Wonderful fliers, dazzling and resplendent in the sunshine when they are most abundant. Certain very slender species are known as damsel flies.

Hope’s narration also hints at broader concerns and views about insects in the early 20th century, some of which continue today.

BLATTIDAE – COCKROACHES

A large family of wide distribution. The more familiar species are household pests, scuttling rapidly to cover in the cracks and corners of the floors. They are not all disgusting looking creatures, some East Indian forms being beautifully colored.

What do we need to know to understand the natural world? What do we need to show to convey it? Johnson collected, labeled, and described it, and gave us a record of the nature we knew. Hope edited and interpreted it, and gave us a record of our relationship to it. Our insect diversity survey drawer tries to do all of the above. When people view our insect diversity survey drawer in 60 or 120 years, how will they characterize it? Will they note our outdated scientific knowledge and use of hilariously antiquated paper and pins? In the context of the global insect population collapse, the Wagner’s survey is a drop in an Aral Sea of missing data, a bud from the Garden of Babylon. Might the insect diversity survey drawer become precious scientific evidence of global insect population changes, or in its brevity and neutrality, damning evidence of our inaction as insects vanished? In this era of rapid, human-propelled change, the yard drawer is both a progression and a reflection.

ORDER VIII HEMIPTERA (RHYNCHOTA)

The forms included in this order are known as “bugs” […] The bugs are an ancient group, rather isolated in their geberal [sic] characters from the other insect orders. They are our enemies. As David Sharp says— “there is probably no order of insects that is so directly connected with the welfare of the human race as the Hemiptera; indeed if anything were to destroy the enemies of the Hemiptera, we, ourselves should probably be starved in the course of a few months. […]”

Learn More:

Wagner Free Institute of Science video about the malaise trap project and Adam's sorting work

KYW: Philly expert offers insight on studies that raise fear of 'insect apocalypse'

100% of the SBD rewards from this post will support the continuation of a fellowship program at the Wagner Free Institute of Science.

Hello @phillyhistory! This is a friendly reminder that you have 3000 Partiko Points unclaimed in your Partiko account!

Partiko is a fast and beautiful mobile app for Steem, and it’s the most popular Steem mobile app out there! Download Partiko using the link below and login using SteemConnect to claim your 3000 Partiko points! You can easily convert them into Steem token!

https://partiko.app/referral/partiko

Congratulations @phillyhistory! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!