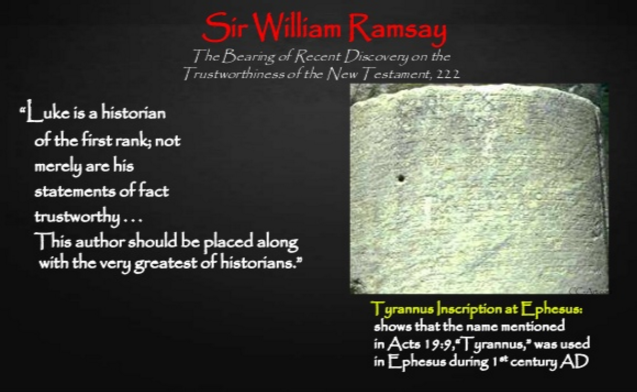

I see that there are several active posts attempting to question the historical veracity of the Bible. Clearly the attackers have not run across Sir William Ramsay: "First Professor of Classical Archaeology" and "Lincoln and Merton Professorship of Classical Archaeology and Art" at Oxford, and "Regius Professor of Humanity" at the University of Aberdeen, if you are into academic titles.

I'm grabbing a few snippets from his Wikipedia biography which as far as I'm concerned puts the question of historical veracity of Biblical accounts to rest. Here we have a skeptical archeologist who set out to prove once and for all that the New Testament was fiction. He wound up proving the opposite and became a Christian himself.

William Ramsay was known for his careful attention to New Testament events, particularly the Book of Acts and Pauline Epistles. When he first went to Asia Minor, many of the cities mentioned in Acts had no known location and almost nothing was known of their detailed history or politics. The Acts of the Apostles was the only record and Ramsay, skeptical, fully expected his own research to prove the author of Acts hopelessly inaccurate since no man could possibly know the details of Asia Minor more than a hundred years after the event—this is, when Acts was then supposed to have been written.

He therefore set out to put the writer of Acts on trial.

He devoted his life to unearthing the ancient cities and documents of Asia Minor. After a lifetime of study, however, he concluded: 'Further study … showed that the book could bear the most minute scrutiny as an authority for the facts of the Aegean world, and that it was written with such judgment, skill, art and perception of truth as to be a model of historical statement' (The Bearing of Recent Discovery, p. 85). On page 89 of the same book, Ramsay accounted, 'I set out to look for truth on the borderland where Greece and Asia meet, and found it there [in Acts]. You may press the words of Luke in a degree beyond any other historian's and they stand the keenest scrutiny and the hardest treatment...'

When Ramsay turned his attention to Paul's letters, most of which the critics dismissed as forgeries, he concluded that all thirteen New Testament letters that claimed to have been written by Paul were authentic.

Chris White is an excellent researcher, debunker & apologetic. Here is some of his research regarding the Bible.

These are very well done and answer most of the questions people have been sharing here recently.

I think these deserve to be their own post, so they don't get buried way down here.

Appeal to authority is a logical fallacy. Plus, we've learned a lot since his time.

When the alternative is to appeal to the opinions of the inexperienced, uncredentialed and uneducated? This forum is full of personal opinions stated as if they were facts. I offer an unquestionable expert who spent his life documenting those opinions.

So, to counter the actual scientific consensus of today, you dig out a single opinion from the past? From a time, when our knowledge especially in the field of archeology was still vastly inferior? No expert has ever been unquestionable and William Mitchell Ramsay is exactly one of those, whose findings have been thoroughly refuted by the facts we since uncovered.

Just curious. What facts?

thanks in advance for your response :)

Read my Steemit blog. In coming weeks, I'm posting a book full of such facts. So far I've only used published the introduction. Much more to come.

Have you read Ramsay's books and came to a conclusion that they are great work? Or do you just bring up the name because he supports your point of view?

You might want to check also some authors who have more critical view about history of the Bible, like Bart Ehrman.

Usually I look first for most recent authors if the question is about history. Ramsay died in 1939 and knowledge about history of Bible has been advanced after that. Maybe Ramsay had something interesting to say, but it might be better to start with more recent authors if you really want to learn higher quality information.

If you need a more recent author it's hard to beat Josh McDowell. He is the author of some 115 books and references Ramsay's research as part of a comprehensive tour of the evidence behind Christianity. I've even had the pleasure of hearing him speak.

While scientific knowledge undoubtedly advances and therefore Einstein's understanding supersedes Newton's, the uncovering of archeological evidence confirming historical accounts never goes out of style.

So called "evidence" from "textual analysis" presented by "modern" authors designed to cast doubt on ancient documents is typically of the form "here's a place where I could interpret things differently" or "there is no corroborating proof" that what the author said is true or that "remarkable claims demand remarkable proof." They are never of the form "here is irrefutable evidence that the work is a false account."

As an objective professional researcher, Ramsay proved that Luke was a first class historian who knew about things that no subsequent pretender could have known. That kind of information never goes out of date.

Ehrman has his fan club but so does Ramsay. Josh D. Chatraw has criticized Ehrman for the way he cites the "modern scholarly consensus" in support of his claims: "It is only by defining scholarship on his own terms and by excluding scholars who disagree with him that Ehrman is able to imply that he is supported by all other scholarship." Elsewhere, Chatraw suggests Ehrman writes "with a charismatic and appealing style" for a lay audience, but argues that "Ehrman represents a segment of biblical scholarship which he often implies is the only legitimate brand of scholarship, and he rarely exposes lay readers to the best arguments of opposing views."

Look, I don't care (I should, but I don't) whether people want to put their head in the sand and deny the historical accounts that Christianity is based on. I certainly don't want to waste my time arguing with people whose mind is made up and don't want to be confused with the facts. The only reason I bother to point this out at all is to help those who are seeking the truth have a chance of actually finding it in the modern hostile environment (which the Bible also foresaw).

Those who are seeking God will find Him and those who don't want to find Him will not seek.

So be it.

I watched a few videos from Youtube and didn't like what I saw. He clearly has biases to interpret all evidence like it supports him.

This video is clearly wrong:

It is well known that scribes have been making a lot of mistakes during the years, both accidentally and intentionally (to fabricate the message to support their own viewpoints). And of course we have the problem that God didn't make any material to explain how certain passages should be translated to other languages.

This is clearly not only a problem of the past, but there are also many different sects of christianity today. That proves without any doubt that God failed with his communication.

But what that proves? If you think that is a sufficient evidence, then you have a big problem because you have to evaluate same kind of evidences for other religions, too. Many religions have even better evidence for their views about supernatural (more written records, more recent authors).

Just because a religious text has some historical stuff that is right doesn't mean that the whole religion is right.

If you study about the proofs that have been made with textual analysis, you'll see that many of them are really good. There are a lot of versions of the same texts. Some differences are clearly accidents, but some are made intentionally to support a certain theological viewpoint. There are of course room for discussion what individual differences really mean but the overall picture is clear: There are a lot of different versions of christian texts but God hasn't clearly communicated which ones of them are right.

If you like facts, why don't you read more from authors like Ehrman and ignore people like McDowell (who clearly has religious bias)? Ehrman might have some problems too, but clearly he is much more unbiased. If you read reviews of his books from Amazon, you'll see that many believers have left a positive comment. He is not attacking faith, he is just documenting his results of studying the original texts.

What exactly you mean by "the truth"? As I have pointed out, there are several different sects of christianity. Those have so different views that they can't all be true at the same time. Which one of them you believe in? Why do you think that is the right one and all others are wrong?

I've always found this to be quite baffling. On the one hand, christianity is supposed to be a religion for everyone. But on the other hand, achieving the real faith is really difficult. The message is unclear and doesn't make any sense, and it has to be spread out by humans (God himself doesn't want to do that).

How many individuals do you think have found the truth today? There has been 2000 years to spread the message, but most people haven't accepted it. There are still lots of other religions, and christianity itself is also divided. Then there are also a lot of people who belong to church but don't have faith.

The reasons why God chose to do things this way are above my pay grade. The best I can figure out is what I've said: it is His intention to leave room for people to find an excuse not to believe while providing enough to satisfy "he who has ears to hear."

If you were deciding who to adopt into your family from a population of people who you have given free will, presumably you would want to see who you could trust. So you let the candidates spend a few decades on a test range where you learn whether they will seek to find you or go their own way. You don't want to make finding you so obvious that even those who reject you go along grudgingly. You want to make it very easy for those folks to walk away.

Of course, being all-knowing, you already know how the test will turn out but you still have to run the test anyway so that all creation can see that everyone had a fair chance.

Being all-powerful, you could force everyone to comply, but that's not who you want in your family. You want people who love you for Who you are and who obey you because of that love.

There is no doubt that Christianity has fragmented into thousands of different teachings, which is why I use the term "Biblical Christianity" as the standard, not any particular denomination or sect. Any teachings that make an honest attempt to anchor themselves in what is written there are going to be close enough and we can agree to disagree on how to best understand them.

Stuff that has been made up outside the canonical scriptures should be treated with a different standard as merely the non-binding, unofficial opinions of men. That doesn't necessarily mean it's wrong -- unless it contradicts Scripture. For example, choices about the proper ways to show respect and implement God's wishes can vary widely. That leads to countless variations that differ in worship style and content, but not in the fundamental message.

The fundamental message is blindingly simple and no amount of real or imagined gotchas in the text can change that:

Yet somehow, most humans can't bring themselves to do that. They would rather nit-pick whether certain texts are historically perfect or not. They would rather question God's motives or play logical games about whether there can be free will if God knows everything or not.

None of that matters. Therefore, most of the things various splinter groups argue about don't matter. That's just a distraction to avoid facing the main issue:

Jesus has stated that, sadly, he doesn't expect most of the human race to accept that offer.

The offer is open to everyone.

But so is the choice to walk away.

You inspired me to write this: https://steemit.com/christianity/@samupaha/hey-christians-you-may-give-me-all-your-money

There are many things in the Bible that christians don't take seriously, and being poor is one of them. Jesus is quite clear on this matter: you just can't get into Heaven if you have too much money. Preferably you should sell everything that you have and then donate all your money.

Oh man, it so difficult to answer you. You don't make anything clearer but instead present more absurd points. Full answer would take several hours to write.

So I'll just say this as a general answer: Try to look things from a point of view of an atheist.

The message that you think is clear is far from it. Bible is mixed bag of old texts that are hard to understand. Try someday read the gospels as a person who doesn't believe in God and doesn't know anything about christianity. If you can do this, you'll realize that it is quite weird shit.

I agree that the Bible can be hard for a noob to understand. It has taken me 62 years to get to my current inadequate level of understanding, despite teaching over 600 hours of college-level courses on the subject. The learning never stops.

But you reject the above ELI5 version, which is not too hard to understand, as "absurd". It is not absurd, it is all you need to accept to have eternal life in Heaven.

If you don't like reading the Bible directly, or my off-hand draft posts, there are tons of books that break it down. "Christianity for Dummies" or "Mere Christianity" by CS Lewis are good starting places.

You should be able to believe this: A credible ex rocket scientist and adult sunday school teacher who has achieved Hero status on both bitcointalk and bitsharestalk is telling you that it would be worth your while to take this seriously.

If such a person told you that there was credible evidence of buried treasure in your back yard would you refuse to go inform yourself about how to find it?

This is the greatest of all treasures.

You are definately not addressing Jewish scribes, called Masoretes, with this misinformation. If you were to research them you would find that your "well known" information above has absolutely no relevance to the Mesoretes whatsoever.

Here are some highlights :

And on and on and on. Feel free to research this if you like for there is far more to the Masoretes than I have listed above. I just wanted to point out the gross negligence in your statement above.

I haven't had time to read any of Erhman's books, but since you recommended it I did start to investigate. First step, read some reviews. Here is one of the top reviews which at least attempted to be even handed.

Stan

345 of 428 people found the following review helpful

3.0 out of 5 stars Notable for what Ehrman gets right as well as what he gets wrong, March 28, 2014

By Robert M. Bowman Jr.

This review is from: How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee (Hardcover)

Bart Ehrman’s book How Jesus Became God is the most recent example of a scholarly tradition of books offering to explain how Christianity turned a simple itinerant Jewish teacher into the Second Person of the Trinity. Already the skeptics are giving the book obviously partisan five-star reviews. Rather than engage in book review “star wars” by giving the book only one star I am giving it three stars, even though as a biblical scholar of an evangelical Christian point of view I strongly disagree with the thesis of the book.

Ehrman’s thesis is that Jesus was not viewed, by himself or his disciples, as in any sense divine during his lifetime, but that belief in his divinity arose almost immediately after his disciples had visions of Jesus that they interpreted as meaning that God had raised him bodily from the dead. According to Ehrman, the earliest Christians thought Jesus had been exalted by God to a divine status at his resurrection, but this belief quickly morphed, resulting in the idea that Jesus was God incarnate. The premise of his argument is that the category of divinity was an elastic one in the ancient world, even to some extent in Jewish thought, and so first-century Christians were able to entertain quite different conceptions of what it meant to regard Jesus as divine or even as “God” (a point Ehrman elaborates in two chapters, 11-84).

Having laid the foundation, Ehrman builds the house of his theory of Christian origins. Jesus was an apocalyptic preacher who mistakenly thought the end of the age was imminent and who hoped he would become the Messiah (a merely earthly king) in the impending age to come (86-127). Instead, he was executed by crucifixion and his body was probably not even given a decent burial, contrary to the Gospels (133-65). However, a few of Jesus’ disciples who had fled to Galilee had some visions of Jesus, perhaps of the type people sometimes have when they are bereaved (174-206). The disciples interpreted these visions almost immediately as meaning that Jesus had risen from the dead to an exalted, divine status in heaven as God’s adopted “son” next to God himself. Ehrman finds this earliest “exaltation Christology,” dating from the early 30s, in preliterary creedal statements imbedded in Paul (Rom. 1:3-4) and Acts (2:36; 5:31; 13:32-33), even though he recognizes that neither Paul nor Luke held to this view (216-35).

Ehrman thinks this exaltation Christology developed with extreme rapidity into what is the more recognizable view of Christ. By the 40s or at the latest the 50s, some Christians thought Jesus had become God’s Son at his baptism or at his birth, while others, such as Paul, thought Jesus was God’s Son even before his human life, serving as God’s chief angel (240-69). This angelic incarnation Christology was developed before the end of the century into the idea of Jesus as God incarnate, seen especially in John and Colossians, which Ehrman denies Paul wrote (269-80). Christian leaders of the second and third centuries hardened this incarnation Christology into a standard of orthodoxy, rejecting Christologies of their day akin to those of the earliest Christians attested in various parts of the New Testament. This process of defining orthodoxy and condemning heresy eventually led to the formulation of the doctrine of the Trinity and its codification in the creeds of the fourth and fifth centuries (284-352).

As I see it, Ehrman gets a surprising number of things right. Jesus was a real historical person. The New Testament Gospels are our best source of information about that person. Jesus was crucified at the order of Pontius Pilate and died on the cross. Some of Jesus’ original followers sincerely believed not long afterward that they saw Jesus alive from the dead. Already, we’ve eliminated about 90 percent of the nonsense we so often hear from skeptics about Jesus, and we’re not done yet. Ehrman agrees that the earliest Christians regarded Jesus as in some sense divine and that within about twenty years, even before Paul, at least some Jewish Christians believed that Jesus was a preexistent divine being. (Skeptics usually try to blame this idea on Paul.) The belief that Jesus existed before creation as God (and yet not God the Father) arose even before the Gospel of John. One could hardly wish for more agreements and even concessions from the world’s most influential agnostic biblical scholar.

Having given credit where credit is due, I must move on to identify what I think are some of the weakest links in Ehrman’s argument. For sake of brevity I limit the list to five.

Ehrman presents three models of the divine human in Greco-Roman culture: “gods who temporarily become human” (19-22), “divine beings born of a god and a mortal” (22-24), and “a human who becomes divine” (25-38). He admits that the case of Jesus does not fit any of these: “I don’t know of any other cases in ancient Greek or Roman thought of this kind of ‘god-man,’ where an already existing divine being is said to be born of a mortal woman” (18). He could have added to that sentence, “or Jewish thought.” This is the Achilles’ heel of Ehrman’s whole account of Christian origins. By his own admission, the Christian view of Jesus—a view he admits emerged within twenty years of Jesus’ crucifixion—was literally unprecedented.

Ehrman’s main thesis on its face appears completely lacking in credibility. According to Ehrman, whereas Jesus did not view himself as anything more than a man and did not expect to become anything more than a glorious earthly king, within a few weeks or months of Jesus’ death his original followers were sincerely proclaiming that Jesus was a divine figure ruling over all creation at God’s right hand in heaven. Apparently Jesus’ original disciples, who had walked all over Galilee and Judea with him and listened to him teach for hours on end, simply discounted Jesus’ own self-image as nothing more than the future human Messiah.

To make his theory work, Ehrman has abandoned his earlier view that the burial of Jesus in a tomb just outside Jerusalem was historically likely. He now accepts something like John Dominic Crossan’s view that Jesus received no decent burial at all. In a way, denying the tomb is a smart move on Ehrman’s part. As long as he acknowledged both the tomb and the appearances, he remained vulnerable to the vise grip of the historical argument for the Resurrection. So Ehrman, who knows he cannot deny that at least some of the disciples had experiences in which they thought they saw Jesus alive from the dead, has gone the more sensible skeptical route and questioned the burial in the tomb. But this move, while sensible enough from his agnostic perspective, lands him in evidential hot water, because the evidence that the Gospels are telling the truth about the empty tomb is very good. Craig Evans, in his chapter in the book How God Became Jesus that responds to Ehrman’s book, does an excellent job of critiquing Ehrman on this point.

Ehrman’s attempts to explain the appearances of Jesus naturalistically ignore entirely the testimony of the apostle Paul that Jesus had appeared to him when Paul was still a persecutor of Christians. Ehrman quietly omits any mention of Paul’s experience throughout his treatment of the resurrection appearances in the fifth chapter of his book. Then, having finished with the subject of Jesus’ resurrection, at the beginning of chapter 6 Ehrman says only that Paul, after converting to faith in Jesus, “later claimed that this was because he had had a vision of Jesus alive, long after his death” (214, emphasis added). That is all he says—and it is difficult even to take his statement seriously. That Paul sincerely thought he had a vision of the risen Christ is really beyond debate. That fact is a stubborn datum that Ehrman failed to incorporate into his account of the origins of the Christian movement.

Ehrman labors to defend the premise that the apostle Paul thought Jesus was the chief angel come in the flesh. He has one proof text for this claim—Galatians 4:14, where Paul reminds the Galatians that when he visited them they welcomed him “as an angel of God, as Christ Jesus.” Ehrman takes this statement to mean that Jesus is an (or the) angel of God. However, it is far more likely that Paul’s language is progressive or ascending: the Galatians treated him as if he were an angel of God, and even as if he were Christ Jesus himself (for similar constructions in Greek, see Psalm 34:14 LXX; 84:14 LXX; Song of Sol. 1:5; Isa. 53:2; Ezek. 19:10). Earlier in the same passage, Galatians 4:4-6 shows that Paul thought of the Son and the Spirit as two divine persons sent by God the Father—one of numerous proto-Trinitarian passages in Paul.

Ehrman has done the church a service by reminding us that the issues of the resurrection of Christ and the deity of Christ are inextricably linked. He has also thrown down a challenge to Christian scholars to make the case for both of these truths in a fresh way that engages the evidence within a broader range of religious studies. His own theory, however, suffers from some various serious—one might say grave—flaws. I have offered a more detailed review of his book on the Parchment and Pen blog.

Did you choose this one just because it supports your view or because it is really a truthful review? Maybe you should first read some books and then decide how good the criticism is.

I chose it because it was at the top of the critical views list with 345 of 428 readers finding it useful.

The points it mentions that the author was making uniformly are speculation about what is "likely" to have happened in lieu of what the eyewitnesses clearly state did happen. Really? This passes as your idea of top quality analysis?

For example, He says Jesus was "probably not given a decent burial" discounting every eyewitness's detailed accounts, such as:

Similarly, regarding when people started believing Jesus was God Himself wrapped in human flesh he comes up with a flimsy speculation of what "probably happened" long after the fact. But the Bible is full of quotes acknowledging Jesus deity: "Doubting Thomas" touched his resurrected body and then address him as "My Lord and My God" without rebuke.

Jesus said "Anyone who has seen me has seen the Father (God)" and many other places the Jewish leaders picked up stones to throw at him when he claimed to be God.

Even the prophets acknowledged that the coming Messiah would be recognized and called God, for example Isaiah the Prophet wrote this 700+ years Before Christ :

The idea that Jesus evolved into God years later is dead on arrival. And therefore so is my first impression of this author.

I have studied many independent english translations from the original Greek.

What I don't trust is modern liberals with a revisionist agenda. :)

But for the sake of argument, even if you make the case that during a "drafting period" several sets of pre-existing notes were referenced and used in producing more than one of the 4 gospels (Matthew and Mark seem to share some common passages) that doesn't change in the smallest way the key facts about God that run through all 66 books of the Bible and the references to them found in the writings of the early church fathers. You would have to introduce ten thousand changed verses to obliterate the underlying message that God has been laying down for over 3500 years and more than 40 different authors - all hanging together to tell a consistent story. The fact is that all of the 5600 surviving manuscripts dating back to that first generation say the same thing. Trying to cast doubt on bits of trivia doesn't change the essence of the Gospel.

First, you can't rely on english translation only. You should look at original texts and see what they really say and how reliable they are. There are many cases where experts are quite sure that some text is either added or changed later. I haven't read that particular book but I guess that this is how Ehrman proves his points.

Second, you can't trust those eyewitness testimonials. They were not written by eyewitnesses themselves, but by somebody else much later. If you think that is ok to trust those testimonials, then you have to trust also many, many other religious testimonials, including people who don't have christian faith.

How can your experience be anything but Reality? And if God is Reality, aren't you then part of God? What do facts matter? How can words and concepts do more than hint at the Truth?

The father, the son, the holy spirit; the source, the flesh, the understanding; the tri-unity; what if it's all pointing to an underlying truth that we can all experience, here and now? What if Jesus was a Bodhisattva, what if Buddha was a Christ? The word is flesh, always fresh and vibrant, otherwise it is a lie.

Watch out for dead thoughts in dead tongue. Concepts can become corpses, words can be zombies. What does it really mean to live in the truth, live in the light?

What are we afraid of? What casts shadows on everything? What steals away in the night? What reveals, what blinds? What is hiding, what is seeking? Who can accept, who can forgive, who can appreciate All Things?

The idea that other beliefs can be held simultaneously with Christianity is immediately falsifiable because they contradict each other. You have to choose. Christianity is fundamentally a historical religion grounded in real historical events dating back 6000 years. So its perfectly reasonable to talk about history as His Story.

Jesus himself spoke about these times, as captured in Matthew 24:4-14: