Run amok AI’s have become a very common sci-fi trope, even though Hollywood gets much of it wrong for the sake of an exciting story. One of the reasons this topic is so fascinating to me is that this doomsday scenario, until very recently, was something we as a civilization didn't really think to worry about. The danger of floods, fires, diseases, war, etc., has been troubling humanity since the beginning of time, but the idea that we would create intelligences far greater than our own – and that it would be our downfall – is, I think, something that we haven't even imagined until recently. What other catastrophic risks could potentially exist that we are unable to imagine yet?

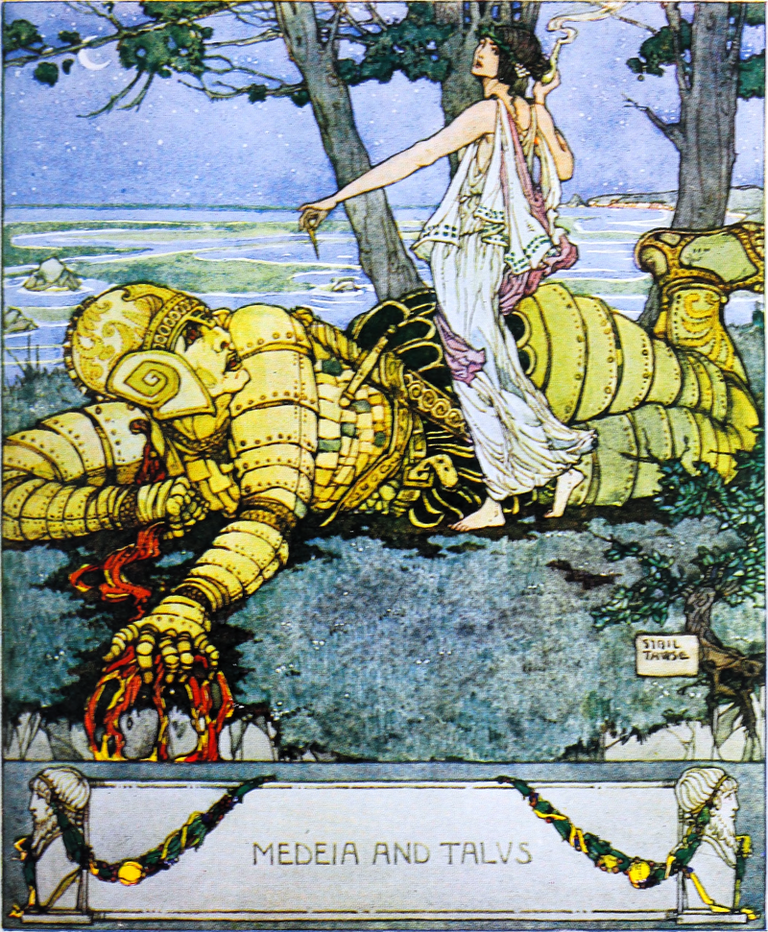

The idea of creating animate life is old as all of humanity. In Greek Mythology is mentioned a giant bronze robot, Talos, that defeated pirates around the island of Crete. Almost all societies have stories about automatons or automata (you can check out the history of AI from this Wikipedia page) and even more common are stories of statues or other lifeless objects being animated by divine intervention, but they rarely possess greater intelligence than what is required of them to act as reliable servants or soldiers. Interestingly, in Hellenic Egypt (circa 200 B.C.), Hero of Alexandria mentions elaborate theatrical performances with flames, dancing priestesses and elaborate mechanical puppets that, despite being controlled by a human priest, were believed to posess ka – a soul. These puppets could speak and dispense wisdom, while the pupeteer was believed to behave as some sort of medium.

Medeia and Talus by Sybil Tawse. Wikipedia.

I wonder if the thought process leading to the idea of automatic beings might have been something like the following. When early inventors looked at a water wheel, they might have pictured a mechanically more complicated version that could perform additional tasks, other than simply turning a millstone to grind grain into flour. They might have wondered if a craftier design could empty the grain from the sack into the mechanism automatically, instead of having that task being done by a miller, then add the flour back into the sack, lift it onto a cart, and cut out the middleman entirely. Money could be saved like that, instead of it going to the miller's cut. But, better yet, what if this mill was so cleverly designed that it could also be mobile? Perhaps a windmill on wheels, that were powered by wind power. It could come to the farm, instead of requiring the farmer to take their cartload to the mill. That's additional time and work saved.

Imaginations run wild and now there’s the idea that perhaps this machine could do additional tasks, like harvest the wheat on its own. That way you could manage much larger fields without hiring extra labor. Something like a very primitive robot. Clever mechanical engineering could reduce the size of this machine. It could be given arms to allow it to use already existing human tools. That way you could have one machine do many different things, instead of having a separate machine for every particular task, something like standardization.

You could have it decide for itself when the wheat is ready for harvesting – further offloading work from the busy farmer. Mechanical logic gates could have the contraption cut the wheat when it’s of a certain height. A machine like that would be extremely complex, but there’s nothing about it’s construction that would, to the early inventor, seem potentially undoable or impossible. Everything this robot does is a causal result of something else happening in this world. From a distance it would appear this robot is alive and consciously deciding to cut the wheat because it is ready for harvesting, but you would know that there’s a gear turning inside it somewhere that made it decide in that way. If the early inventor let his imagination run even wilder, he could envisage a machine that could even talk. Maybe it would require thousands and thousands of tiny turning cogwheels to manipulate a pipe organ and would be astonishingly complicated, but no laws of physics would suggest that it’s impossible.

However ingeniously this machine was designed, it would still lack the ability for abstract thinking, or to reason, be creative or original since it would always return the same action and result dependent on the initial conditions. Simply put, like a fancy calculator, which can tell you what 2+2 is, but not what the concept of a number is. The Google search engine, which is also a form of AI, is similar. It can understand human writing, albeit without any real comprehension, to search through a nearly limitless database of information. What we want is an artificial general intelligence, or AGI.

Higher level abstract thinking would require it to manipulate information in a wide-ranging way, to use already acquired and stored knowledge to create new models and network and interact them with each other. A mechanical computer, even if it could hold information, even digitally in the form of bits, would be too slow and too cumbersome for any complex information processing. And modern artificial neural networking technology, which a lot of AI research is based on, would be nearly impossible. Nearly. There's something that strikes us as weird about an intelligent AI that doesn't run on electricity. It almost feels impossible. However, down at the atomic level, a mechanical computer with gears and an electricty-powered supercomputer both work on the same principles of electromagnetism. It's just that we have come to associate robots and computers with electricty, by interacting daily with electronic devices.

Computers wouldn’t have been beyond the imagination of ancient people. While Charles Babbage (1791 –1871) is often regarded as the father of the computer, mechanical calculators were certainly a thing even in ancient times. The Antikythera mechanism, created by Hellenistic astronomers, is more than 2000 years old and was used to predict eclipses and stars. I’m sure the inventors were imaginative enough to conceive of an even more capable calculator. But something that a mechanical calculator would lack, even if placed inside a humanoid robot, is consciousness. By the way, consciousness is something that a modern version of artificial intelligence, e.g. C-3PO or SkyNet, does not necessarily have to have. We frequently see AI in movies that is sentient, but it is possible to have a super intelligent and highly competent AI that lacks consciousness entirely. It could decide that humanity should be destroyed or, conversely, that the next most logical step is to help humanity reach greater flourishment, but it would be a decision reached by unconscious arithmetic. It could even run virtual simulations of millions of humans, each one a conscious entity with thoughts, emotions and feelings, albeit in virtual space. But the AI itself, after it has run the required number of simulations to reach its goal of finding out some truth about humans, could destroy these simulations and continue on without any sentience of its own. Consciousness itself, however, is a fuzzy complicated thing that we haven’t fully understood yet.

When it comes to ancient civilizations, intelligences far greater than ours were relegated to the gods. The plausibility of mankind creating an automaton with an intelligence that of humans or greater still, was hard to believe. Mainly because for the longest of times, we as humans have regarded our own minds originating from something other than a purely physical source. Humans were enchanted by a divine spark or a soul. That kind of attitude is still widespread nowadays in religious teachings. It was thought that an automaton, created by humans, would lack such a soul. It could only do tasks that were given to it, but it couldn't imagine or have motivations other than serving its masters.

Only after sufficient knowledge was gathered about the human mind and neurology, coinciding with early progress in computer science, that we have come to accept that there is no physical limit in simulating intelligences greater than our own. There's no missing soul requirement in assembling a brain. With this realization, so came the realization of what that too would entail. The possibility of creating sentient minds that exist in not only wetware but hardware, not only in vivo but in silico. This is where the field of AI research is now. But what other mediums we could use to simulate a brain? I'll write about just that in the next post.