Hello dear friends, today the topic dealt with will be genetic mutations as a cause of disease, in this first episode we will make a brief review of what mutations are, how they are classified and what effects they can cause at the molecular level, we will analyze the pathogenetic pathway of B-thalassaemias going then to evaluate the clinical picture, then we will start from a molecular approach to conclude to study the evolution of a mutation in clinical and pathological terms.

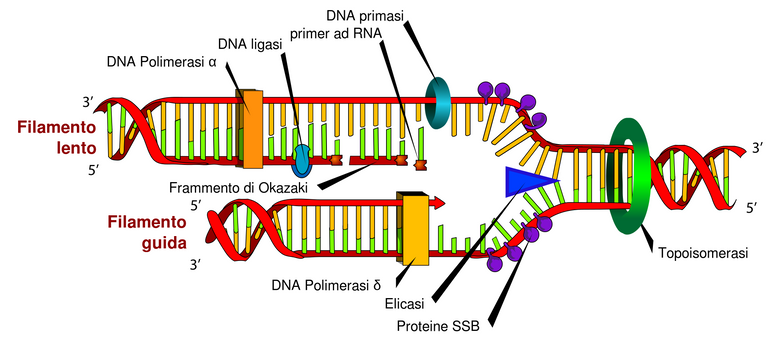

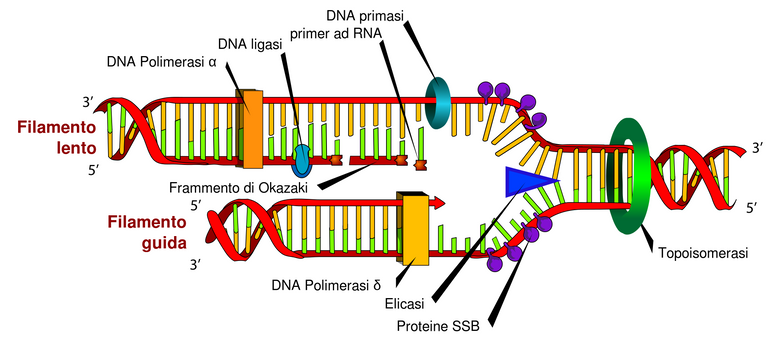

GENE MUTATIONS

Genome alterations, i.e. mutations, are sudden and irreversible alterations of the structure and function of the genome.

genetic material.

Mutations can cause different types of pathology depending on the cell type in which they occur and the gene affected:

for example, mutations involving gametic cells are far more severe than mutations involving cells

somatic, as the genes contained in them will surely be used for the development of the organism; in the same way,

mutations involving unused genes from the cell will be pathognomically irrelevant.

Therefore, not all mutations lead to pathological effects, i.e. there is a disjunction between genotype and phenotype: in

these cases the mutation occurs, but either it is repaired (an event that depends on the time that passes between the onset of the

mutation and cell division), is either silent (synonymous or on silenced genes) or occurs on a differentiated cell

terminally, characterized by a limited number of active genes and a large number of unused genes, or the

mutation is the cause of cell death.

In case the mutation is not cancelled by one of these mechanisms, if it happens in the gametic cells it will give

originates a hereditary disease; on the contrary, if it concerns oncogenes and oncosuppressants of a somatic cell, it will originate

to a tumor.

You can make a quantitative classification of mutations, which divides them into:

Gene mutations: they compromise a single gene

Chromosomal mutations: affect the functioning of several genes on the same chromosome.

Genomic mutations: they modify the number of chromosomes of an individual.

The pathogenic potential, i.e. the probability that the various mutations give rise to disease and that it is severe, is strictly

correlated with the number of genes involved; however, the greater the severity of the disease, the greater the probability and precocity

with which the death of the sick individual occurs and therefore it follows that most hereditary diseases

known are the gene mutations since these are disvital and allow the affected individual to reach age

fertile.

Mutations can occur at the level of both encoding and non-coding sequences of a gene; a

depending on the structure involved in the mutation, the probability that these cause disease does not change, since both

the two regions are necessary for the functionality of the gene involved. However, if the mutation occurs in a sequence that does not

If it occurs in a coding sequence there will be a quantitative alteration, if it occurs in a coding sequence there will be a qualitative mutation.

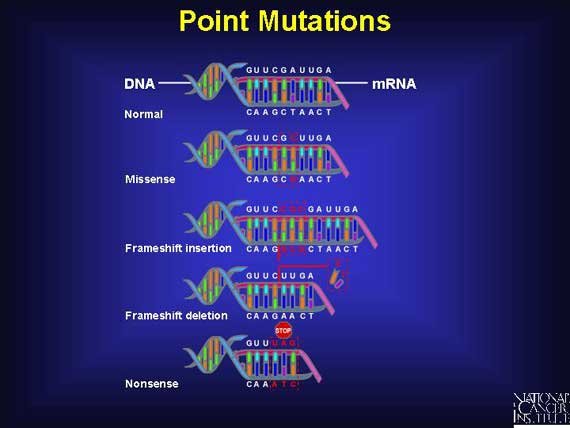

Gene mutations can be point or non-point mutations.

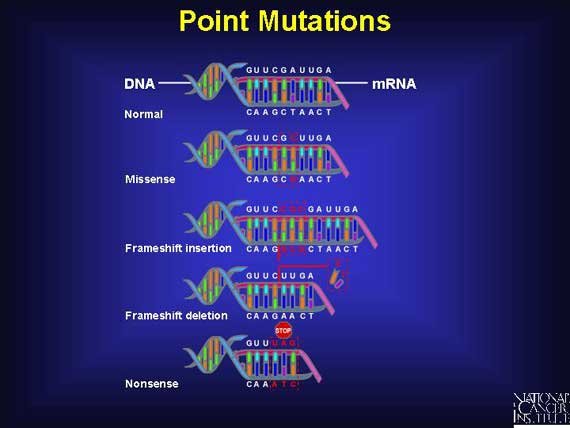

Point mutations are represented by the substitution of one nitrogen base with another (transversion, transition).

These mutations can be of different types:

Mutations missense: determined by replacing one aa with another in the nascent polypeptide chain. Can

cause phenotypic effects or be conservative.Synonymous mutations: mutation that does not lead to substitution of an amino acid in the polypeptide chain

and never has a phenotypical effect.Non-sense mutations: mutation that leads to the formation of a stop sequence: the resulting protein will be as follows

shorter than wild type. Alternatively, a stop tail may undergo a mutation and become coding: the protein will be longer than the wild type.

Non-point-shaped mutations include deletions, insertions, inversions, gene duplications; this type of mutation

usually gives more serious phenotypic effects than punctiformes:

Insertions/deletions of a number of base pairs equal to 3 or a multiple of 3: you get a polypeptide chain

shorter or longer than one or more aaInsertions/deletions of a number of base pairs other than 3 or a multiple thereof: you get the phenomenon of

frameshift, which is a completely different protein from the wild type and therefore deleterious.

A gene disease is always determined by a mutation and the pathway from mutation to clinical onset of the

disease is called pathogenesis. The pathogenesis of these diseases can undergo interruptions, i.e. the gene mutation does not

corresponds more to the phenotypical manifestation. The pathogenetic path therefore includes:

Genic alteration: alteration at the level of the nitrogen base sequence. The interruption occurs for example with

synonymous mutations (e.g. replacement of the third ATA triplet with a G and formation of the ATG triplet)Primary alteration: alteration at the level of the amino acid sequence. The interruption occurs with mutations

conservative (e.g.: aspartate instead of glutamate).Secondary alteration: alteration of the structure/function of the coded protein. The interruption may occur

if the mutation has completely nullified the gene (such as the promoter/enhancer deletion that

prevents the binding of RNA polymerase and therefore the gene is not transcribed and therefore the protein is absent) or

if the mutation is in heterozygous form, i.e. if the affected subject will produce 50% wild type protein, without

develop disease.Tertiary alterations: pathological manifestations at the biochemical-clinical level.

- Quaternary alterations: actual disease.

MOLECULAR BASIS OF β-TALASSEMIES

β-thalassaemias are quantitative hereditary disorders of haemoglobin synthesis, in which a genetic defect results in a

reduction or abolition of β globin chain synthesis.

The β chain gene is located on chromosome 11 together with a delta gene, a gene and two beta pseudogens and two y genes.

It consists of 3 exons, 2 introns (important for the RNA stability and splicing process) a poly-A sequence in 3'

(involved in transcript stability) and a promoter in 5'that regulates the speed and amount of transcription.

Depending on the defect characterizing the B-globin gene, B-thalassaemias can be classified in:

B+ Thalassaemia, characterized by a reduced synthesis of the B chain

B0 thalassemia, characterized by a lack of synthesis

Hb Lepore, characterized by the fusion of delta and beta genes

Hb Kenya, characterized by the fusion of Ay and beta genes.

HPFH, characterized by the persistence of fetal hemoglobin even in adulthood

The severity of the phenotype is determined both by the quantitative effect of the mutation of a single gene but also by the different

genotypical structure that derives from it, since a mutation into heterozygosity has completely different consequences compared to

to a mutation into homozygosity.

In fact, a β0 mutation completely cancels the production of the β gene, for this reason, if present in homozygosity,

will lead to sub lethal disease while, if present in heterozygosity, it will lead to a 50% production of HbA, and

despite some clinical manifestations, the heterozygous patient for this mutation will be able to lead a life

acceptable and to reproduce.

β thalassaemias are generally not caused by deletions of the β gene (which typically cause Hb Lepore or

Kenya), but rather by point mutations of exons, introns, control sequences, consensus sequences or

flanking regions.

Classifying mutations from early to late we will have 4 main types of mutation associated with secondary defects:

mRNA non-functional: They are usually frame-shift mutations or nonsense mutations, which therefore always give

a non-functional mRNA (beta° for the mutated allele) which is degraded by proteases.

Examples of nonsense mutations are the Chinese beta° thalassemia, characterized by T-A on codon 17 at formation

of a protein of 16aa instead of 146aa, and the Mediterranean beta thalassemia, characterized by a transition G

A on tail 39 (38aa on wild type 146aa). The McKees Rock variant is different, because the mutation is on the 144th

tail on 146 and then you will have a beta+ variant totally indistinguishable from a wild beta chain production

type.Alterations of the processing of the RNA: they are mutations that happen either in the consensus sequences, in the flanking

regions or in introns. Consensus sequences and flanking regions play a peculiar role in the process of

RNA splicing.

The consensus sequences are double bases of GT and AG situated between introns and exons which

make the endonucleases excide the intron at a specific point, thus avoiding mutations.

frameshift. The flanking regions, on the other hand, form a sequence of 5-10 nucleotides before and after the base pair

of the consensus sequences: these structures make the ANN assume a three-dimensional structure that is

recognized by the splicing enzyme.

A mutation affecting the two bases of consensus sequences will lead to an incorrect splicing process,

with transcript degradation.

An example could be the Mediterranean beta thalassemia, which sees guanine replaced with

an adenine. It is intuitable that this lack of final transcript is the cause of a beta thalassemia on the allele.

mutated.

A point mutation can also determine a new consensus sequences in the intron, by mutation

punctiform. In this case the new sequence will be called cryptic consensus sequence and the splicing enzymes

will alternately recognize both splicing sequences. The result in this case will therefore be,

statistically, 50% of the final product changed and degraded and 50% intact and functional: it is therefore

a beta+ variant.

Transcription-altering mutations, which take place in the promoter sequences (where RNA

polymerase) and in enhancer sequences.Mutations at the polyadenylation site: this site allows the stability of the mature transcript once migrated into the

cytosol because it protects it from the nucleases present. As the mRNA is translated, the nucleases digest the site of

polyadenylation.

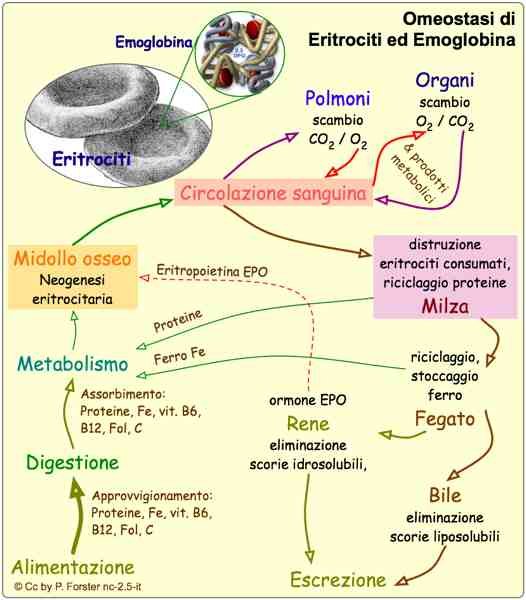

PATOGENESIS OF β-TALASSEMIA (COOLEY DEAD)

β-thalassaemia major or Cooley's disease is the quantitative haemoglobinopathy with the most severe phenotype among β-

thalassemias.

It is defined by its main cynical manifestation, a serious form of anaemia.

The clinical classification of beta thalassemia major is due to the severity of the anemia, which in turn depends on the type

of gene defect in homozygosity (B or B+ or Hb lepore). Medical onset occurs in 60% of cases in the first year of life.

in homozygous patients B0, the most severe form of the disease, and in 10% over two years old in homozygous patients Lepore, the most severe form of the disease.

mild of illness.

Patients with this severe anaemia have haemoglobin concentrations below 6g/dl.

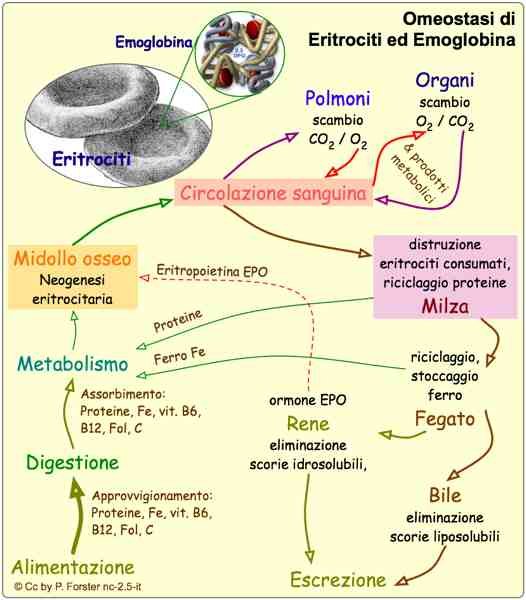

Anemia is a condition that lies between molecular defect and clinical manifestations; a reduced synthesis of β chains may

lead to two events happening in parallel.

First of all, at the medullar level, the remaining 4 α chains join together to form a totally deleterious tetrameter of α4: these

tetrameres precipitate into the erythroblasts to form the included bodies, which cause a change in the shape of the erythroblast

himself. The erythroblast thus constituted has a reduced survival and is apoptosis inside the marrow,

resulting in ineffective erythropoiesis; in the event that the erythroblast manages to escape from the marrow, it becomes

erythrocyte, it would still find difficulties in the capillary microcirculation because it would not be able to deform and would

thus witnessing the phenomenon of peripheral hyperhemolysis.

In addition, erythroblasts with included bodies entering the bloodstream are seized by the hemocateretic system consisting of the spleen.

and liver: these organs will work to eliminate the deleterious red blood cells, and therefore, because of their enormous work of

hematocateresis, a hepatosplenomegaly picture with possible compression of the abdominal organs.

Parallel to this, a selective survival of HbF is observed in the bone marrow. Since a

HbF is characterized by a greater affinity for 02, it is more difficult to release oxygen to the tissues, thus determining

tissue hypoxia.

This situation of hypoxia is perceived at the kidney level, which responds by increasing the production of

Erythropoietin: This hormone increases bone marrow activity for increased red blood cell production which due to the

of the lack of b-chain, produces an increase in erythrocytes including bodies, which again results in

ineffective erythropoiesis.

Ineffective erythropoiesis and peripheral hyperhemolysis are mainly responsible for the condition of

Cooley's patient's anemia.

The marrow and hemocateretic organs require entirely the reduced amount of oxygen present in the body for

perform their activities, and in this way deprive the brain and muscles of oxygen, causing mental retardation and cachexia.

The increased metabolic activity of the bone marrow also determines its expansion both at the level of bones in which normally

is not present (skull, face bones), either at the level of bones in which it is physiologically present causing serious abnormalities

skeletal and compromising bone growth. In addition, the exalted erythropoiesis occurs at the expense of the production of

of platelets and neutrophils, causing plateletstrinopenia (at the base of hemorrhagic diathesis) and neutropenia (at the base of deficit

immune).

Ineffective erythropoiesis leads to an increased demand for iron, to which the intestine responds by absorbing it in quantity

and causing siderosis. Iron is toxic for the liver (where it causes cirrhosis and fibrosis), for the marrow (where it aggravates the

situation, stimulating erythropoiesis and accentuating platelet and neutropenia), for the endocrine system (where it poses

the basis for the development of diabetes, hypothyroidism and thyroid disorders) and in the heart, causing cardiomyopathies which will then lead to

to the patient's death.

The only treatment available is transfusions that patients with Cooley's disease have to undergo.

periodically. However, transfusions also lead to iron overload and aggravate the situation, and furthermore

are causing hypervolemia, offset by increased heart activity. The use of iron chelators allows the patients

suffering from this severe anemia to survive until the age of about 30.

Gene therapies aimed at modifying diseased genes are currently being studied.

Ciao a tutti cari amici, oggi l'argomento trattato saranno le mutazioni genetiche come causa di malattia, in questo primo episodio faremo un breve ripasso su cosa sono le mutazioni, come vengono classificate e che effetti possono causare a livello molecolare, andremo ad analizzare il percorso patogenetico delle B-talassemie andando poi a valutare il quadro clinico, partiremo quindi da un approccio molecolare per arrivare in conclusione a studiare l'evoluzione di una mutazione in termini clinici e patologici.

MUTAZIONI GENICHE

Le alterazioni del genoma, ovvero le mutazioni, sono alterazioni improvvise e irreversibili della struttura e della funzione del

materiale genetico.

Le mutazioni possono causare diversi tipi di patologia in base al tipo cellulare in cui avvengono ed in base al gene colpito:

ad esempio, mutazioni che coinvolgono le cellule gametiche, sono di gran lunga più gravi di mutazioni che interessano cellule

somatiche, in quanto i geni in esse contenute saranno sicuramente utilizzati per lo sviluppo dell’organismo; allo stesso modo,

mutazioni che coinvolgono geni inutilizzati dalla cellula, saranno ininfluenti dal punto di vista patognomico.

Pertanto, non tutte le mutazioni determinano effetti patologici, ovvero esiste una disgiunzione tra genotipo e fenotipo: in

questi casi la mutazione avviene, ma o viene riparata (evento che dipende dal tempo che passa tra l’insorgenza della

mutazione e la divisione cellulare), o è silente (sinonima o su geni silenziati) o avviene su una cellula differenziata

terminalmente, caratterizzata da un numero limitato di geni attivi e da un grande numero di geni inutilizzati, o ancora, la

mutazione è causa di morte della cellula.

Nel caso in cui la mutazione non venga annullata da uno di questi meccanismi, se avviene nelle cellule gametiche essa darà

origine a una malattia ereditaria; al contrario, se riguarda oncogeni e oncosoppressori di una cellula somatica, darà origine

a un tumore.

È possibile fare una classificazione quantitativa delle mutazioni, che le divide in:

Mutazioni geniche: compromettono un solo gene

Mutazioni cromosomiche: compromettono il funzionamento di più geni sullo stesso cromosoma.

Mutazioni genomiche: modificano il numero di cromosomi di un individuo.

La potenzialità patogena, ovvero la probabilità che le varie mutazioni diano malattia e che questa sia grave, è strettamente

correlata con il numero di geni interessati; tuttavia, maggiore è la gravità della malattia, maggiore è la probabilità e precocità

con cui avviene la morte dell’individuo malato e pertanto ne consegue che la maggior parte delle malattie ereditarie

conosciute sono le mutazioni geniche poiché queste sono disvitali e permettono all’individuo affetto di raggiungere l’età

fertile.

Le mutazioni possono verificarsi sia a livello delle sequenze codificanti, sia a livello di quelle non codificanti di un gene; a

seconda della struttura coinvolta dalla mutazione, la probabilità che queste causino malattia non cambia, poiché entrambe

le due regioni sono necessarie alla funzionalità del gene coinvolto. Tuttavia, se la mutazione avviene in una sequenza non

codificante si avrà un’alterazione quantitativa, se avviene in una sequenza codificante si avrà una mutazione qualitativa.

Le mutazioni geniche possono essere puntiformi o non puntiformi.

Le mutazioni puntiformi sono rappresentate dalla sostituzione di una base azotata con un’altra (trasversione, transizione).

Queste mutazioni possono essere di diversi tipi:

Mutazioni missenso: determinate dalla sostituzione di un aa con un altro nella catena polipeptidica nascente. Può

causare effetti fenotipici oppure essere conservativa.Mutazioni sinonima: mutazione che non determina la sostituzione di un amminoacido nella catena polipeptidica

nascente e non ha mai effetto fenotipico.Mutazioni non senso: mutazione che porta alla formazione di una sequenza di stop: la proteina risultante sarà così

più corta della wild type. Alternativamente, un codone di stop può subire una mutazione e diventare codificante: la proteina sarà più lunga rispetto alla wild type.

Le mutazioni non puntiformi comprendono delezioni, inserzioni, inversioni, duplicazioni geniche; questo tipo di mutazione

dà solitamente degli effetti fenotipici più gravi rispetto alle puntiformi, e si distinguono:

Inserzioni/delezioni di un numero di paia di basi uguale a 3 o a un multiplo di 3: si ottiene una catena polipeptidica

più corta o più lunga di uno o più aaInserzioni/delezioni di un numero di paia di basi diverso da 3 o da un suo multiplo: si ottiene il fenomeno di

frameshift, che costituisce una proteina completamente diversa dalla wild type e per questo deleteria.

Una malattia genica è sempre determinata da una mutazione e il percorso che porta dalla mutazione all’esordio clinico della

malattia è detto patogenesi. La patogenesi di queste malattie può subire delle interruzioni, ovvero la mutazione genica non

corrisponde più alla manifestazione fenotipica. Il percorso patogenetico dunque comprende:

Alterazione genica: alterazione a livello della sequenza delle basi azotate. L’interruzione si verifica per esempio con

mutazioni sinonime (es sostituzione nella tripletta ATA della terza A con una G e formazione della tripletta ATG)Alterazione primaria: alterazione a livello della sequenza amminoacidica. L’interruzione si verifica con mutazioni

conservative (es: aspartato al posto di glutammato).Alterazione secondaria: alterazione della struttura/funzione della proteina codificata. L’interruzione può avvenire

se la mutazione ha completamente annullato il gene (come per esempio la delezione promoter/enhancer che

impedisce il legame della RNA polimerasi e pertanto il gene non viene trascritto e quindi la proteina è assente) o

se la mutazione è in forma eterozigote, ovvero se il soggetto affetto produrrà il 50% di proteina wild type, senza

sviluppare malattia.Alterazioni terziarie: manifestazioni patologiche a livello biochimico-clinico.

- Alterazioni quaternarie: malattia conclamata vera e propria.

BASI MOLECOLARI DELLE β-TALASSEMIE

Le β-talassemie sono disordini ereditari quantitativi della sintesi di emoglobina, nei quali un difetto genetico comporta una

riduzione o un’abolizione della sintesi della catena β globiniche.

Il gene della catena β è localizzato sul cromosoma 11 insieme a un gene delta, un gene e due pseudogeni beta e due geni y.

È costituito da 3 esoni, 2 introni (importanti per la stabilità dell’RNA e il processo di splicing) una sequenza poli-A in 3’

(coinvolta nella stabilità del trascritto) e un promoter in 5’che regola la velocità e la quantità di trascrizione.

In base al difetto che caratterizza il gene della B- globine, le B- talassemie possono essere classificate in:

B+ Talassemia, caratterizzata da una ridotta sintesi della catena B

B0 talassemia, caratterizzata da una mancata sintesi

Hb Lepore, caratterizzata dalla fusione dei geni delta e beta

Hb Kenya, caratterizzata dalla fusione dei geni Ay e beta

HPFH, caratterizzata dalla persistenza dell’emoglobina fetale anche in età adulta

La gravità del fenotipo è determinata sia dall’effetto quantitativo della mutazione di un singolo gene ma anche dal diverso

assetto genotipico che ne deriva, in quanto una mutazione in eterozigosi ha conseguenze completamente differenti rispetto

a una mutazione in omozigosi.

Infatti, una mutazione β0 annulla completamente la produzione del gene β, per tale motivo, se presente in omozigosi,

porterà ad una malattia sub letale mentre, se presente in eterozigosi, porterà ad una produzione del 50% di HbA, e

nonostante alcune manifestazioni cliniche, il paziente eterozigote per questa mutazione riuscirà a condurre una vita

accettabile e a riprodursi.

Le β talassemie generalmente non sono causate da delezioni del gene β (che invece tipicamente causano Hb Lepore o

Kenya), ma piuttosto da mutazioni puntiformi a carico di esoni, introni, sequenze di controllo, consensus sequences o

flanking regions.

Classificando le mutazioni dalla più precoce alla più tardiva avremo 4 tipi principali di mutazione associati a difetti secondari:

mRNA non funzionali: Sono solitamente mutazioni frame-shift o mutazioni nonsenso, che pertanto danno sempre

un mRNA non funzionale (beta° per l'allele mutato) il quale viene degradato dalle proteasi.

Esempi di mutazioni non senso sono la beta° talassemia cinese, caratterizzata da T-A sul codone 17 alla formazione

di una proteina di 16aa al posto di 146aa, e la beta ° talassemia mediterranea, caratterizzata da una transizione G

A sul codone 39 (38aa su 146aa della wild type). Diversa è la variante McKees Rock, perché la mutazione è sul 144°

codone su 146 e quindi si avrà una variante beta+ totalmente indistinguibile da una produzione di catena beta wild

type.Alterazioni del processing dell’RNA: sono mutazioni che avvengono o nelle consensus sequences, nelle flanking

regions o negli introni. Le consensus sequences e le flanking regions svolgono un ruolo peculiare nel processo di

splicing dell’RNA.

Le consensus sequences costituiscono doppiette di basi di GT e AG situate a cavallo tra introni ed esoni le quali

fanno in modo che le endonucleasi vadano a excidere l’introne in un punto preciso, evitando così mutazioni

frameshift. Le flanking regions costituiscono invece una sequenza di 5-10 nucleotidi prima e dopo la coppia di basi

della consensus sequences: tali strutture fanno in modo che l’RNA assuma una struttura tridimensionale che venga

riconosciuta dall’enzima di splicing.

Una mutazione che colpisce le due basi della consensus sequences porterà ad un incorretto processo di splicing,

con degradazione del trascritto.

Un esempio può essere la beta talassemia mediterranea, che vede la guanina sostituita con

una adenina. È intuibile come questa mancanza di trascritto finale sia causa di una beta° talassemia sull'allele

mutato.

Una mutazione puntiforme può anche determinare una nuova consensus sequences nell'introne, per mutazione

puntiforme. In questo caso la nuova sequenza verrà definita consensus sequence criptica e gli enzimi di splicing

riconosceranno alternativamente entrambe le sequenze di splicing. Il risultato quindi in questo caso sarà,

statisticamente, un 50% di prodotto finale mutato e degradato e un 50% integro e funzionale: si tratta pertanto di

una variante beta+.

Mutazioni che alterano la trascrizione, le quali avvengono nelle a sequenze promoter (dove si lega l’RNA

polimerasi) e nelle sequenze enhancer.Mutazioni nel sito di poliadenilazione: questo sito permette la stabilità del trascritto maturo una volta migrato nel

citosol poiché lo protegge dalle nucleasi presenti. Mentre l’mRNA viene tradotto, le nucleasi digeriscono il sito di

poliadenilazione.

PATOGENESI DELLA β-TALASSEMIA (MORBO DI COOLEY)

La β-talassemia major o morbo di Cooley è l’emoglobinopatia quantitativa che presenta il fenotipo più grave tra le β-

talassemie.

Essa si definisce mediante la sua manifestazione cinica principale, ovvero una grave forma di anemia.

La classificazione clinica della beta talassemia major è dovuta alla gravità dell’anemia, la quale a sua volta dipende dal tipo

di difetto genico in omozigosi (B o B+ o Hb lepore). L’esordio medico infatti avviene nel 60% dei casi nel primo anno di vita

in pazienti omozigoti B0, forma più grave della malattia, e nel 10% oltre i due anni in pazienti omozigoti Lepore, forma più

lieve della malattia.

I pazienti affetti da questa grave anemia hanno concentrazioni di emoglobina inferiori a 6g/dl.

L’anemia è una condizione che si colloca tra difetto molecolare e manifestazioni cliniche; una ridotta sintesi di catene β può

portare a due eventi che accadono in parallelo.

Innanzitutto, a livello midollare, le restanti 4 catene α si uniscono a formare un tetramero di α4 totalmente deleterio: questi

tetrameri precipitano negli eritroblasti a formare i corpi inclusi, i quali causano un cambiamento di forma dell’eritroblasto

stesso. L’eritroblasto così costituito ha una ridotta sopravvivenza e va incontro ad apoptosi all’interno del midollo,

determinando un’eritropoiesi inefficace; nel caso in cui l’eritroblasto riuscisse ad uscire dal midollo, esso trasformandosi in

eritrocita, troverebbe comunque delle difficoltà nel microcircolo capillare poiché non sarebbe in grado di deformarsi e si

assiste così al fenomeno di iperemolisi periferica.

Inoltre, gli eritroblasti con corpi inclusi entrati in circolo vengono sequestrati dal sistema emocateretico costituito da milza

e fegato: questi organi lavoreranno per eliminare i globuli rossi deleteri, e quindi, a causa del loro enorme lavoro di

emocateresi, viene a configurarsi un quadro di epatosplenomegalia con eventuale compressione degli organi addominali.

Parallelamente a questo, nel midollo osseo si nel midollo osseo si assiste a ha una selettiva sopravvivenza di HbF. Poiché a

l’HbF è caratterizzata da una maggiore affinità per l’02, essa cede più difficilmente l’ossigeno ai tessuti determinando così

ipossia tissutale.

Questa situazione di ipossia è percepita a livello del rene, il quale risponde aumentando la produzione di

eritropoietina: questo ormone aumenta l’attività midollare per una maggiore produzione di globuli rossi la quale a causa

della mancanza delle catene b, produce un aumento di eritrociti contenti corpi inclusi, e ciò si traduce nuovamente in

eritropoiesi inefficace.

L’eritropoiesi inefficace e l’iperemolisi periferica sono i principali responsabili della condizione di

anemia del paziente affetto da morbo di Cooley.

Il midollo e gli organi emocateretici richiedono interamente la ridotta quantità dell’ossigeno presente nell’organismo per

compiere le loro attività, e in questo modo privano di ossigeno il cervello e i muscoli causando ritardo mentale e cachessia.

L’aumentata attività metabolica del midollo osseo determina anche la sua espansione sia a livello di ossa in cui normalmente

non è presente (cranio, ossa della faccia), sia a livello di ossa in cui è presente fisiologicamente causando gravi anomalie

scheletriche e compromettendo l’accrescimento osseo. Inoltre, l’esaltata eritropoiesi avviene a discapito della produzione

di piastrine e neutrofili, causando piastrinopenia (alla base di diatesi emorragica) e neutropenia (alla base di deficit

immunitari).

L’eritropoiesi inefficace conduce a una maggiore richiesta di ferro, alla quale l’intestino risponde assorbendolo in quantità

maggiori e causando siderosi. Il ferro è tossico per fegato (dove causa cirrosi e fibrosi), per il midollo (dove aggrava la

situazione, stimolando l’eritropoiesi e accentuando la piastrinopenia e la neutropenia), per il sistema endocrino (dove pone

le basi per lo sviluppo del diabete, ipotiroidismo e turbe tiroidee) e nel cuore, causando cardiomiopatie che porteranno poi

alla morte del paziente.

L’unica cura disponibile è rappresentata dalle trasfusioni alla quale i pazienti affetti dal Morbo Di Cooley devono sottoporsi

periodicamente. Tuttavia, le trasfusioni determinano anch’esse un sovraccarico di ferro aggravando la situazione, ed inoltre

sono causa di ipervolemia, compensata da una maggiore attività del cuore. L’utilizzo di chelanti del ferro permette ai pazienti

affetti da questa grave anemia di sopravvivere fino all’età di circa 30 anni.

Attualmente sono in studio terapie geniche volte alla modifica dei geni malati.

Fonti/Sources

Immagini/Pictures

Questo post è stato condiviso e votato all'interno del discord del team curatori di discovery-it.

This post was shared and voted inside the discord by the curators team of discovery-it

Hello,

Your blog caught my eye because it has the word 'thalassaemias'. I carry this trait, without notable symptoms, except for yielding consistently peculiar blood tests. Of course, any family that has evidence of this trait has to emphasize the importance of genetic counseling. Also, anyone who has this trait should be cautioned against iron overload (which you allude to in your blog). Young women don't run this hazard but men and older women do. One more curiosity: there may be an association between this trait and the development of autoimmune diseases.

Since my family has both the trait and an elevated incidence of autoimmune disease, I found this interesting.

Thanks for translating from Italian--that would have been a challenge.

forse la consulenza genetica riguarda proprio qualsiasi patologia....chissà!!!

This post has been voted on by the SteemSTEM curation team and voting trail. It is elligible for support from @curie and @minnowbooster.

If you appreciate the work we are doing, then consider supporting our witness @stem.witness. Additional witness support to the curie witness would be appreciated as well.

For additional information please join us on the SteemSTEM discord and to get to know the rest of the community!

Please consider using the steemstem.io app and/or including @steemstem in the list of beneficiaries of this post. This could yield a stronger support from SteemSTEM.