The third section of Chapter IV of Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval is called Ice Age in the Tropics. In this section, Velikovsky recounts how one of the pioneers of the Ice Age Theory, Louis Agassiz, discovered evidence for an Ice Age in equatorial Brazil. Many of the tell-tale signs that had indicated the presence of ice sheets in northern Europe—glacial drifts, erratics, U-shaped valleys, and glacial till—were also to be found in the tropics of South America. Similar evidence was uncovered in British Guiana, equatorial Africa, Madagascar and India. Not only had these regions been covered by ice sheets, but there was unmistakable evidence that in some cases those ice sheets had spread from the equator to higher latitudes. In India, there was even evidence that the ice had spread up the Himalayas from the lowlands.

Curiously, Velikovsky does not cite a single work in support of this evidence. He does, however, open this section with the words:

In 1865, Agassiz went to equatorial Brazil ... (Velikovsky 36)

And, indeed, it is Agassiz whom he is paraphrasing in the opening paragraph. Agassiz published the results of his trip in A Journey in Brazil, which was co-authored by his wife Elizabeth Cabot Agassiz and published in 1868. Although the voyage to South America was undertaken for reasons of health, Agassiz had no intention of taking a holiday from his geological pursuits. Surprisingly, he went to South America convinced that he would find more evidence for the Ice Age—even in the tropics:

The existence of a glacial period, however much derided when first announced, is now a recognized fact. The divergence of opinion respecting it is limited to a question of extent ; and after my recent journey in the Amazons, I am led to add a new chapter to the strange history of glacial phenomena, taken from the southern hemisphere, and even from the tropics themselves.

I am prepared to find that the statement of this new phase of the glacial period will awaken among my scientific colleagues an opposition even more violent than that by which the first announcement of my views on this subject was met. I am, however, willing to bide my time; feeling sure that, as the theory of the ancient extension of glaciers in Europe has gradually come to be accepted by geologists, so will the existence of like phenomena, both in North and South America, during the same epoch, be recognized sooner or later as part of a great series of physical events extending over the whole globe. Indeed, when the ice-period is fully understood, it will be seen that the absurdity lies in supposing that climatic conditions so different could be limited to a small portion of the world's surface. If the geological winter existed at all, it must have been cosmic; and it is quite as rational to look for its traces in the Western as in the Eastern hemisphere, to the south of the equator as to the north of it. Impressed by this wider view of the subject, confirmed by a number of unpublished investigations which I have made during the last three or four years in the United States, I came to South America, expecting to find in the tropical regions new evidences of a bygone glacial period, though, of course, under different aspects. Such a result seemed to me the logical sequence of what I had already observed in Europe and in North America. (Agassiz 398-399)

In the following forty pages, Agassiz enumerates all the observations that led him to conclude that even here in the scorching tropics there had once been glaciers and ice sheets. He believed that this was evidence of a single global Ice Age of fairly recent occurrence:

It is my belief that all these deposits belong to the ice-period in its earlier or later phases, and to this cosmic winter, which, judging from all the phenomena connected with it, may have lasted for thousands of centuries, we must look for the key to the geological history of the Amazonian Valley. I am aware that this suggestion will appear extravagant. But is it, after all, so improbable that, when Central Europe was covered with ice thousands of feet thick; when the glaciers of Great Britain ploughed into the sea, and when those of the Swiss mountains had ten times their present altitude; when every lake in Northern Italy was filled with ice, and these frozen masses extended even into Northern Africa; when a sheet of ice, reaching nearly to the summit of Mount Washington in the White Mountains (that is, having a thickness of nearly six thousand feet), moved over the continent of North America, is it so improbable that, in this epoch of universal cold, the valley of the Amazons also had its glacier poured down into it from the accumulations of snow in the Cordilleras, and swollen laterally by the tributary glaciers descending from the table-lands of Guiana and Brazil? (Agassiz 425)

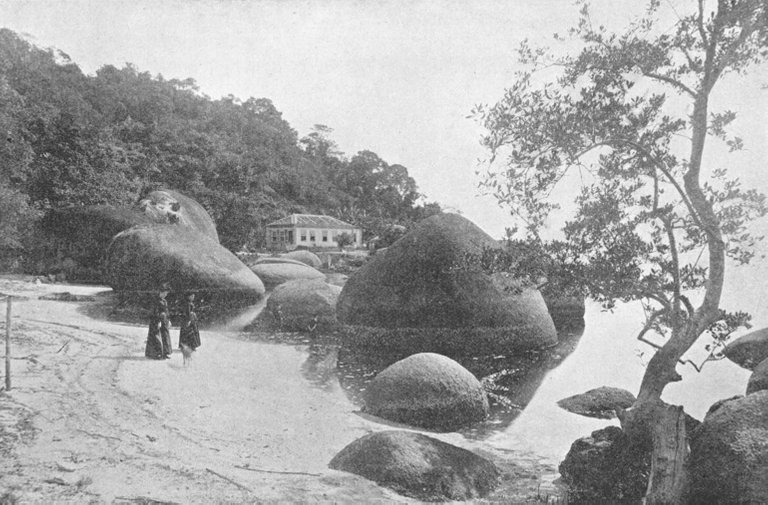

Agassiz admits that he did not find any trace of the furrows, striæ, and polished surfaces so characteristic of the ground over which glaciers have travelled (Agassiz 426). It is, therefore, quite odd that Velikovsky includes scratched rocks ... and the smooth surface of tillite among the signs of glaciation in the Brazilian tropics (Velikovsky 36). However, as the thumbnail image shows, glacial striations have been discovered in Brazil since Agassiz’s time.

There is also documentary evidence that Agassiz later downplayed his theory of Brazilian glaciation, emphasizing instead the signs of glaciation in the more southerly parts of South America. But he never formally retracted the opinion he had expressed in A Journey in Brazil. See John C Branner’s paper The Supposed Glaciation of Brazil for details.

What about Velikovsky’s references to similar vestiges of glaciation in British Guiana, Africa, Madagascar, and India? These are not taken from Agassiz’s work, and as Velikovsky again fails to cite his sources, I am at a loss to account for them. One of the other authors cited in this section, Carl Dunbar (see below), does mention glaciation in Africa, Madagascar and India (Dunbar 297-298). Although Dunbar notes that in India the ice flowed north, he never goes so far as to claim that it moved uphill, from the lowland up the foothills of the Himalayas (Velikovsky 37).

Late-Paleozoic Icehouse

Agassiz’s theory that there was in the recent past a global Ice Age, triggered by a precipitous drop in temperatures all over the world, is not one that is endorsed by modern glaciologists. Today, the signs of glaciation that Agassiz observed in the tropics are taken as evidence of other Ice Ages that occurred much earlier in the Earth’s history than the recent Pleistocene Ice Age. This is a point which Velikovsky concedes:

On reconsideration, the vestiges of ice in equatorial regions were ascribed to a different ice age that had taken place not thousands but many millions of years ago. Today the glacial phenomena in the tropics and in the Southern Hemisphere are ascribed, in the main, to the Permian Age, a much earlier period than the recent Ice Age. (Velikovsky 37)

Geomorphologists believe that Continental Drift resulted in the formation of a supercontinent, Pangaea, around 335 million years ago [Mya]. The southern part of this continent, Gondwana, was located in the vicinity of the South Pole, and included what would one day be South America, Africa, Madagascar and India—the very continents that preserved a record of this earlier Ice Age. The so-called Late Paleozoic Icehouse is believed to have comprised two major Ice Ages, which were formerly known collectively as the Karoo Ice Age:

Mississippian Karoo Ice Age: 360-320 Mya.

Pennsylvanian Karoo Ice Age: 320-300 Mya.

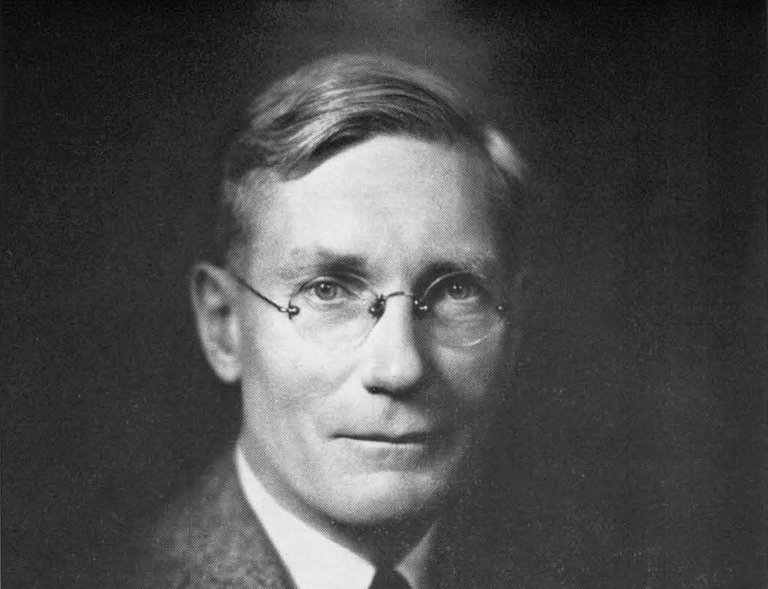

Rollin T Chamberlin

Today, continental drift is accepted as part and parcel of the Theory of Plate Tectonics. Consequently, uniformitarians are no longer embarrassed by the existence of evidence of glaciation in the tropics: these Ice Ages occurred, they argue, millions of years ago, when the affected continents were located close to one of the poles. But Alfred Wegener’s theory of Continental Drift, was still being vigorously debated as late as 1960, almost fifty years since it had been first proposed.

It is not surprising, therefore, to find Velikovsky citing two authors whose books were published in 1937 and 1949—before the general acceptance of continental drift.

The earliest of those authors is Rollin Thomas Chamberlin, who worked for the US Geological Survey in 1907 and 1908 and taught geology at the University of Chicago for almost a quarter of a century, before retiring in 1947, one year before his death. For most of this time, Chamberlin was the editor of the Journal of Geology, a periodical founded and edited by his father, who had also been a geologist, and published by the University of Chicago. He was also an accomplished mountaineer, a skill he put to great use when working in the field. He travelled extensively, visiting all the continents save Antarctica.

Velikovsky quotes from his article The Origin and History of the Earth, which appeared in 1937 in The World and Man as Science Sees Them,, a compilation of science-related articles edited by the American astronomer Forest Ray Moulton, who had been a colleague of Chamberlin’s father in the early 20th century. Chamberlin’s contribution to this anthology describes the origin and geological history of the Earth. It is notable for the complete absence of any mention of continental drift or sea-floor spreading:

At certain times in the Carboniferous and in the succeeding Permian period, which concludes the Paleozoic era, thick sheets of glacier ice covered enormous areas in Australia, northern India, South Africa ... and southern South America, somewhat as Antarctica is ice-bound today. Some of these huge ice sheets advanced even into the tropics, where their deposits of glacier-borne debris, hundreds of feet in thickness, amaze the geologists who see them. No satisfactory explanation has yet been offered for the extent and location of these extraordinary glaciers. they were, however, only one of many strange features of the Permian period. In no other period have we evidence of such widespread arid climates as occurred during its span of time. Glaciers, almost unbelievable because of their location and size, certainly did not form in deserts. But if we realize that there were perhaps 40 million years in the Permian period, the seeming contradiction is understandable in part. The glaciers and the deserts did not occur together. Marked diversity of climate was evidently the rule in these times. How vastly different must have been the living conditions from those when the fern plants were at their peak in the previous period [the Carboniferous]! (Chamberlin 80)

Carl Owen Dunbar

The other scientist Velikovsky cites in this section is Carl Owen Dunbar, an American palaeontologist, who was Professor of Geology at Yale University from 1920 to 1959. He is perhaps best remembered for his college textbook Historical Geology, which was based on the popular textbooks written by his predecessor Charles Schuchert. It went through many editions and reprints, and was still being used as a set book in the 1960s, after his retirement.

Like Chamberlin, Dunbar is not yet prepared to accept the Theory of Continental Drift. Unlike Chamberlain, however, he does concede that the theory could provide a satisfactory explanation of how regions that are today tropical could have been extensively glaciated in the distant past.

The Permian Ice Age. At times during the Permian period great areas in the southern continents were covered with ice sheets ... South Africa has the most spectacular evidence of glaciation, for there the ancient Dwyka tillite at the base of the Permian sequence includes large faceted boulders and rests upon heavily scored and polished floor over which the ice moved ... The ice cap covered practically all of southern Africa up to at least latitude 22° S. and also spread to Madagascar (which was then part of the continent). There were three or four centers of movement, but the greatest seems to have been in the Transvaal, which then was a plateau from which the ice moved southwestward for a distance of at least 700 miles. The tillite reaches a thickness of less than 100 feet in the northeast but increases to 2000 feet in southern Karroo. Australia was likewise the scene of extensive and repeated glaciations, the ice apparently moving northward across Tasmania, Victoria, and New South Wales. A series of five sheets of tillite is interbedded in some 2000 feet of Permian strata which have at least one horizon of commercial coal. South America bears evidence of glaciation in Argentina and southeastern Brazil, even within 10° of the equator. In the northern hemisphere, peninsular India, within 20° of the equator, was the chief scene of glaciation, with the ice flowing north; in the Salt Range on the southern flank of the Himalayas the thick Talchir tillite underlies the marine Permian ...

The most remarkable feature of the Permian glaciation is its distribution. It was chiefly in the southern land masses and in regions which now lie within 20° to 35° of the equator. This circumstance, more than any other, has made attractive ,the belief in “continental drift.” If the southern continents were united to Antarctica until after Permian time, the glaciation may not have spread into low latitudes. A later “drift” of these continents toward the north would account, far more easily than any other means yet postulated, for the present distribution of the glacial deposits. But this premise itself is still in the realm of speculation! (Dunbar 297-298)

Summing Up

This is, perhaps, one of the weaker sections in Earth in Upheaval. Today the idea of continental drift has been successfully incorporated into the uniformitarian doctrine of Plate Tectonics, so there is no compelling reason for uniformitarians to balk at the fact that many of today’s equatorial and tropical regions have been extensively glaciated. On the contrary, today’s uniformitarians use this information to recreate the pattern and timescale of the continental drift.

References

- Louis Agassiz, A Journey in Brazil, Ticknor and Fields, Boston (1868)

- John C Branner, The Supposed Glaciation of Brazil, The Journal of Geology, Volume 1, Number 8, pp. 753-77, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1893)

- Rollin Thomas Chamberlin, The Origin and History of the Earth, in F R Moulton (editor), The World and Man as Science Sees Them,, pp 48-98, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1937)

- Carl Owen Dunbar, Historical Geology, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York (1949)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

Image Credits

- Glacial Striations in the Paraná Basin, Paraná, Brazil: © SamirNosteb, Creative Commons License

- The Extent of the Karoo Glaciations: © GeoPotinga, Creative Commons License

- Alleged Erratic Boulders on Paquetá Island, Rio de Janeiro: John C Branner, Public Domain

- Rollin Thomas Chamberlin: © 1970 National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC, Fair Use

- Carl Owen Dunbar: © 1970 National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC, Fair Use

- Late Carboniferous and Permian Ice Sheet: © 2011 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc, Fair Use

You post has been manually curated by BDVoter Team! To know more about us please visit our website or join our Discord.

Vote @bdcommunity as a Hive Witness.

Are you a Splinterlands player? Get instant 3% cashback on every card purchase on MonsterMarket.io. MonsterMarket has the highest revenue sharing in the space, no minimum spending is required. Join MonsterMarket Discord.

BDVoter Team