Earth in Upheaval Revisited – Part 4

Chapter II of Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval, which is entitled Revolution, opens with a discussion of erratic boulders. An erratic is a rock or boulder that is found in a location where, geologically speaking, it does not belong. If a rock is formed in one place and subsequently transported to another place by a natural—ie non-human—agency, then it’s an erratic.

Erratics come in all shapes and sizes. Velikovsky, quoting G F Wright (p 239), mentions a mass of chalk near Malmö in Sweden three miles long, one thousand feet wide and from one hundred to two hundred feet in thickness, but even this is tiny compared to the Esterhazy megablock in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, which is 38 km long, 30 km wide and up to 100 m thick (Aber, Croot & Fenton 94).

Saussure

Erratics first entered the scientific arena in the late 18th century when the Swiss geologist and mountaineer Horace-Bénédict de Saussure noticed that the southern slopes of the Jura Mountains were strewn with rocks and boulders of Alpine origin:

One will see that the majority of these stones and boulders are made of granite, foliated rocks, or other rocks of Alpine and primitive origin, while the ground on which they have been deposited is composed of limestone or sandstone, and therefore of a completely different nature. One will observe that these stones and large fragments are only ever found on the surfaces of the limestone or sandstone ridges, and that these same ridges never contain the slightest trace of them in their interiors. On the contrary, if one compares each of these stones with those found in the Alps, one will recognize them almost to the point of being able to identify the very rock from which the stone in question was broken off. One will remark that they do not belong to the soil on which they have been cast, and do not resemble the earth that surrounds them, that this same soil has completely different qualities to them, and finally that one finds none of them on the northern slopes of the Jura, but only on those of its slopes which lie opposite the Alps. After having weighed these considerations, one cannot but recognize that these fragments were not formed in this valley, or on the surrounding mountains; but that they are foreign bodies, adventitious, torn from the Alps, their native land, by a powerful agent, which has transported them, rounded their surfaces and piled them up in confusion. (Saussure §206:201-202)

Saussure had no doubt that this powerful agent was water:

§207: That water was this agent cannot in the least be doubted; because these stones, both large and small, are found deposited on horizontal ridges, mixed with sand and gravel, just as water transports them. For if one sees one of these fragments exposed on a rock, inspection of the site alone clearly demonstrates that rainwater or meltwater has carried off the lightest pieces, which formerly surrounded these large masses. (Saussure §207:202)

Velikovsky quotes from Volume I of Saussure’s Voyages dans les Alpes, but his English translation—not credited—is faulty: Saussure’s creuserent de profondes vallées is mistranslated as crossed deep valleys instead of excavated deep valleys.

Les eaux se porterent vers ces abîmes avec une violence extrême, proportionnée à la hauteur qu’elles avoient alors, creuserent de profondes vallées, & entraînerent des quantités immenses de terres, de sables, & de fragmens de toutes sortes de rochers. Ces amas à demi liquides chassés, par le poids des eaux, s’accumulerent jusques à la hauteur où nous voyons encore plusieurs de ces fragmens épars.

The waters were carried towards these abysses with extreme violence, proportional to the height which they then had, excavated deep valleys, and entrained immense quantities of earth, sand, and fragments of all kinds of rocks. These semi-liquid masses, swept along by the weight of the waters, were piled up at the lofty altitude where we still see several of these scattered fragments. (Saussure §210:204-205)

Velikovsky also quotes the paragraph immediately preceding this one, but for some reason the enclosing quotation marks were omitted when the manuscript was set by the printer:

§210: Les eaux de l’Océan, dans lequel nos montagnes ont été formées, couvroient encore une partie de ces montagnes, lorsqu’une violente secousse du globe ouvrit tout à coup de grandes cavités, qui étoient vuides auparavant, & causa la rupture d’un grand nombre de rochers.

§210: The waters of the ocean in which our mountains had been formed still covered a part of these mountains when a violent paroxysm of the globe suddenly opened great cavities, which had been empty formerly, and ruptured many rocks. (Saussure §210:204)

Velikovsky does not translate the clause qui étoient vuides auparavant, which contains the archaic spelling vuides—a potential stumbling block for the inexperienced translator before the advent of the Internet. This suggests to me that Velikovsky himself was responsible for the English translations of Saussure in Earth in Upheaval. I have not found any English translation of Voyages dans les Alpes online. The translations in this article are mine.

Water or Ice

Saussure briefly considered and dismissed the possibility that the Jura erratics were pyroclasts. The idea that the agent of transport was ice never occurred to him. The rounded nature of their surfaces was proof in his eyes that water was the culprit:

§206: But drawing closer to Geneva, if one carefully examines the nature and position of the round stones and rocky fragments that are found in the valley of our Lake [Geneva] and on the neighbouring mountains, one will quickly convince oneself that they have been transported and rounded by water, and that it is quite out of the question that they were formed in the places in which they are now found. (Saussure >§206:200-201)

It is often claimed that another Swiss naturalist, Bernhard Friedrich Kuhn, was the first to suggest that these erratics (Findlinge) had been transported to their present positions by ice, not water. But this is not true: Kuhn’s remarkable essay of 1787 on glacial dynamics did not address the question of erratics. The Scottish geologist James Hutton, however, did. Hutton, it seems, was the first to implicate ice in the transport of erratics. In his Theory of the Earth (1795), he quoted Saussure extensively:

Let us now consider the height of the Alps, in general, to have been much greater than it is at present; and this is a supposition of which we have no reason to suspect the fallacy; for, the wasted summits of those mountains attest its truth. There would then have been immense valleys of ice sliding down in all directions towards the lower country, and carrying large blocks of granite to a great distance, where they would be variously deposited, and many of them remain an object of admiration to after ages, conjecturing from whence, or how they came. Such are the great blocks of granite which now repose upon the hills of Saleve. M. de Saussure, who has examined them carefully, gives demonstration of the long time during which they have remained in their present place. The lime-stone bottom around being dissolved by the rain, while that which serves as the basis of those masses stands high above the rest of the rock, in having been protected from the rain. But no natural operation of the globe can explain the transportation of those bodies of stone, except the changed state of things arising from the degradation of the mountains. (Hutton 2:7:218-219)

Hutton is often seen as the father of Uniformitarianism and the discoverer of deep time. Since his day the problem of erratics has remained a ground of contention between catastrophists and gradualists.

You may have noticed, however, that the Wikipedia article on erratics is called Glacial erratics. Wikipedia is notorious for toeing the mainstream line: dissenting voices are not welcome here : this debate is now closed!

Velikovsky takes his leave of Saussure with a passing reference to Pierre à Martin, a large erratic near Ballaison, close to the southern shore of Lake Geneva, which, he tells us, is over 10,000 cubic feet. What Saussure actually wrote is:

It is called Pierre à Martin. The regular form which this enormous stone most closely resembles is a rectangular parallelepiped. Its maximum height above the ground is 22 feet, its greatest length is 26 feet, and its greatest breadth is 18 feet. (Saussure >§306:342)

American Glaciologists

It is curious that Velikovsky next cites Richard Foster Flint’s Glacial Geology and the Pleistocene Epoch. Flint, a professor of geology at Yale University, was a gradualist. He is remembered today for his dogged opposition to the Missoula Floods hypothesis. He was satisfied that erratics were transported to their present locations by glaciers and ice sheets:

If a stone is foreign to the local bedrock it is an erratic. If, in addition, its place of origin is known by direct comparison with the bedrock there, it is an indicator as well ... Indicators were first recognized by Saussure, a sharp-eyed observer, whose classic description of them has never been improved upon ... In general a line drawn from the locality of an indicator to the locality of its origin parallels the striations and other evidences of direction of glacial flow between the two points. On the other hand the path of travel does not necessarily approximate a straight line inasmuch as the ice may have changed its direction of flow between the time the indicator was picked up and the time it was deposited in its present locality. (Flint 117)

Flint was the source for Velikovsky’s information on three large erratics: the Madison erratic near Conway, New Hampshire : the Ototoks erratic near Calgary, Alberta : and a large mass of Silurian limestone in Warren County, Ohio.

Another American geologist, George Frederick Wright, struggled for much of his career to balance a belief in Western science with his deeply-felt Calvinist faith. He accepted Hutton’s deep time and even defended Darwinian evolution, though he later subscribed to a theory of evolution that left room for intelligent design. One of his works bears the title Scientific Confirmations of Old Testament History. For the last fifteen years of his career he was Professor of Harmony of Science and Revelation at his alma mater, Oberlin College in Ohio. He was largely self-taught in the fields of geology and glaciology—he studied theology at Oberlin (Collopy 1).

Velikovsky cites one of his works, The Ice Age in North America and Its Bearings upon the Antiquity of Man, though he misspells the title. This is not the first time he has been careless with such details. Wright was Velikovsky’s source for information on four large erratics: Mohegan Rock in Montville, Connecticut : the same mass of Silurian limestone in Warren County, Ohio, mentioned by Flint : the aforementioned mass of chalk near Malmö in Sweden : and a similar mass of chalk in England upon which a village had

unwittingly been built (Wright 239).

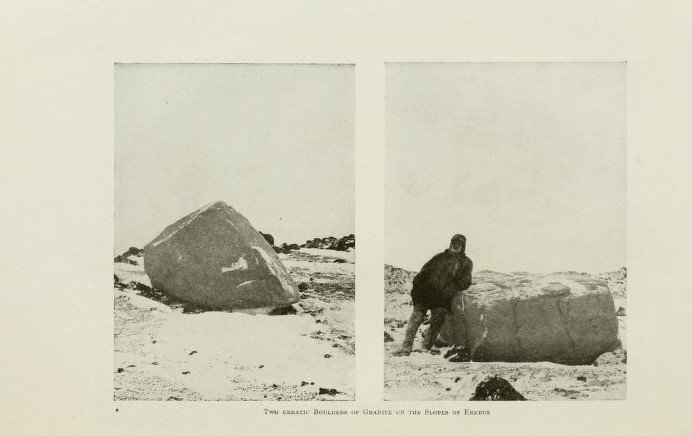

Ernest Shackleton

Velikovsky final source in this section is the Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton, whose record of the British Antarctic Expedition of 1907-09 includes the following photograph of two large granite erratics on the slopes of Mount Erebus:

Unsourced Material

Some quite specific details in this section of Earth in Upheaval are not to be found in any of the four sources Velikovsky cites:

There are erratic boulders in many places of the world. In the British Isles, on the shore and in the highlands, are enormous quantities of them, transported there across the North Sea from the mountains of Norway. Some force wrested them from those massifs, bore them over the entire expanse that separates Scandinavia from the British Isles, and set them down on the coast and on the hills. From Scandinavia boulders were also carried to Germany and spread over that country, in some places so thickly that it seems as though they had been brought there by masons to build cities. Also, high in the Harz Mountains, in central Germany, lie stones that originated in Norway.

From Finland blocks of stone were swept to the Baltic regions and over Poland and lifted onto the Carpathians. Another train of boulders was fanned out from Finland, over the Valdai Hills, over the site of Moscow, and as far as the Don.

I have not yet succeeded in tracking down Velikovsky’s source for these details.

The Erratic Boulders is a curious section of Earth in Upheaval. Velikovsky simply establishes the existence of erratic boulders, without drawing any conclusions. He does not argue that Saussure’s explanation of how they were transported to their final resting places—by cataclysmic floods—must be the right one. Nor does he even mention the competing hypotheses of Hutton and his gradualist disciples. This is a subject which will be explored more fully in Chapter IV, when he returns to the question of the Ice Age.

References

- James S Aber, David G Croot, Mark M Fenton, Glaciotectonic Landforms and Structures, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht (1989)

- Gavin Rylands de Beer, Bernhard Friedrich Kuhn’s Investigations on Glaciers, Annals of Science, Volume 9, Issue 4, pp 323-341, Taylor & Francis, Abingdon, Oxfordshire (1953)

- Peter Sachs Collopy, George Frederick Wright and the Harmony of Science and Revelation, Honors Thesis Submitted to the Oberlin College Department of History (2007)

- Richard Foster Flint, Glacial Geology and the Pleistocene Epoch, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York (1947)

- James Hutton, Theory of the Earth, with Proofs and Illustrations, Volume II, William Creech, Edinburgh (1795)

- Bernhard Friedrich Kuhn, Versuch über den Mechanismus der Gletscher [Essay on the Mechanics of Glaciers], Magazin für die Naturkunde Helvetiens, Volume I, pp 117-136, Johann Georg Albrecht Höpfner, Zürich (1787)

- Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, Voyages dans les Alpes, Volume I, Barde, Manget & Comp, Geneva (1786)

- Ernest H Shackleton, The Heart of the Antarctic: Being the Story of the British Antarctic Expedition 1907-1909, Volume II, J B Lippincott Company, Philadelphia (1909)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

- George Frederick Wright, The Ice Age in North America and Its Bearings upon the Antiquity of Man, Fifth Edition, Bibliotheca Sacra Company, Oberlin OH (1911)

Image Credits

- Motte Stone: © David Quinn, Creative Commons License

- Saussure: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- James Hutton: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Pierre à Martin: Wikimedia Commons, © Björn S, Creative Commons License

- R F Flint: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- G F Wright: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Two Erratic Boulders of Granite on the Slopes of Erebus: Public Domain