I find Philosophy of Mind and Epistemology really interesting. We don't have the answers, but we're getting there. We're making them.

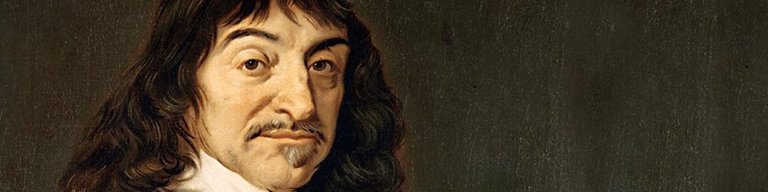

René Descartes (1596-1650) was a crazy genius, philosopher, mathematician and inventor who tried to establish some evidence for the external world in his Meditations on first philosophy.

This is original content by me ( @jonasontheroof )

What can be known of the external world? How can we attain such knowledge at all? In this essay I will present my thoughts on what the influential philosopher René Descartes has told. I will first give a short brief on the epistemic premises Descartes draws out in his Meditations on First Philosophy from 1641. To investigate and criticise these I will present objections from a few of the many who later have taken on this subject, including my own. Then I will look closely at meditation four, five and six to see what evidence I find that proves material things exists somewhere outside mind. And towards the end, a discussion where we will recall and see: What have we learned on the subject from the so-called father of modern philosophy? And at last: Some subject-relevant slam poetry.

To me, meditation is to clear the stream of thoughts. Descartes does the very opposite in his works. But meditation in eastern Buddhist tradition would not be as useful for Descartes' sceptic mission as for what he here has set out – to see if anything can survive his relentless doubt. In the beginning of the first meditation, Descartes rejects all sensuous information (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation one, p. 41). He settles that we cannot trust the senses, because they give different information through different lenses:

Surely whatever I had admitted until now as most true I received either from the senses or through the senses. However, I have noticed that the senses are sometimes deceptive; and it is a mark of prudence never to place our complete trust in those who have deceived us even once. (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation One, p. 41)

Descartes admits that there is sensuous knowledge which is harder to doubt; in example that I have two hands, a fact I am pretty sure about. But although my hands are what they seem, Descartes claims I cannot know whether or not I am having a dream. Therefore no knowledge that I have acquired through my senses is going to pass through these sceptic fences. Now, at this early point in the first meditation, Descartes has excluded all external information. So how are we now going to be able to find knowledge of anything outside the mind? The mind is the place for imagining, and what Descartes is (according to him), is this thinking thing. Though he does not do very much to prove this, and I find this premise hard to agree with; he claims the Cartesian mind is transparent within, so everything there is accessible to him. So a premise for knowledge of the external must be, that it is in the mind a clearly distinct idea. These ideas he can investigate freely, to reveal certain truths ideally. Such ideas can be mathematical truths, geometry and Gods attributes:

Thus it is not improper to conclude from this that physics, astronomy, medicine, and all the other disciplines that are dependent upon the consideration of composite things are doubtful, and that, on the other hand, arithmetic, geometry, and other such disciplines, which treat of nothing but the simplest and most general things and which are indifferent as to whether these things do or do not in fact exist, contain something certain and indubitable. For whether I am awake or asleep, two plus three make five, and a square does not have more than four sides. It does not seem possible that such obvious truths should be subject to the suspicion of being false. (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation One, p. 42)

But this may as well be an illusion for the subject, if God have not made the reasoner perfect. It also could be that the subject was led by an evil daemon to be mistaken instead. This leads Descartes to the only, most basic evident truth; "I think, therefore I am" in his skeptic pursuit (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation One, p. 42-43). It is the only thing for him impossible to doubt; the sceptic fences block all other things out.

In meditation four he comes to rest, regarding God: that He exists and intends the best and nothing bad (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation Four, p. 54). The errors he is capable of committing in his mind, comes from him not being infinite and divine. So the epistemic premises we will deal with further on, does not include that God have made him wrong. Descartes will be carefully aware to not judge anything not distinct and clear. The most important of his premises, is that he cannot trust the senses. The other is the substantial distinction: A mind is a finite, indivisible substance. The body another, which requires extension. And: The external world must be explored and understood nowhere else than in the mind's dimension. If he can settle any knowledge under such a strict condition, it must be the most basic truths of all, that is Descartes' ambition.

Objections to Descartes' Premises

The premises Descartes draws out in his highly influential writings, are radical in their sceptic standards and somehow quite exciting. Though Descartes have influenced many thinkers with his dualist view since the release of his meditations, it now seems clear that this very much has some crucial limitations. Descartes claims that the mind and the body are of substantial different sort, a theory of importance to him that with time fell short – i.e. in light of modern neuroscience, where studies have shown no trace of compliance with his dualist body/mind-alliance. According to Descartes, minds are indivisible, but two "half-minds" simultaneously functioning rejects his mind-substance principle (Gazzaniga, M. S., 1995). Different faculties of the mind operate in or through the different parts of the brain, and activity of consciousness can be traced with neuromagnetism (Hari, R. & Lounasmaa, O. V., 2000). This is modern evidence against Descartes' substance dualism. Other objections Descartes have met, was objections himself was eager to get. He asked for objections from Thomas Hobbes, Antoine Arnauld and many more, and this one (from Hobbes) I think gets right to the core:

[W]hen he appends "that is, a mind, or soul, or understanding, or reason," a doubt arises. For it does not seem a valid argument to say "I am thinking; therefore I am a thought" or "I am understanding; therefore I am an understanding." For in the same way I could just as well say, "I am walking; therefore I am an act of walking." Thus M. Descartes equates the thing that understands with an act of understanding, which is an act of the thing that understands. Or he at least is equating a thing that understands with the faculty of understanding, which is a power of thing that understands. Nevertheless, all philosophers draw a distinction between a subject and its properties and essences; for a being itself is one thing and its essence is another. Therefore, it is possible for a thing that thinks to be the subject in which the mind, reason, or understanding inhere, and therefore this subject may be something corporeal. The opposite is assumed and not proved. Nevertheless, this inference is the basis for the conclusion M. Descartes seems to want to establish. (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, p. 76)

In his reply to this objection, Descartes clearly shows some temper (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, p. 77). But he does not manage to reject this objection in his letter. To Descartes this was not too convincing – he still is, because he is thinking. It seems to me, that what Hobbes here revealed, have empirical backup in the neuroscience field. This "I" that Descartes holds as himself – the non-physical ego – must be a part of the man; or, must it be so? Bennett presents an argument from Voss; that proves "I" can survive, if the concept is tossed:

One of the questions that arises – and Voss raises it – is "So what?" How does Descartes' serious philosophical work need the concept of a man? That question brings into the limelight his understanding of "I". In the meditations he identifies himself with a mind, which he eventually comes to think is intimately associated with an animal body. If he can stick to this through thick and thin, perhaps he can dispense with the concept of a man, but it is easy to see one price he must pay. He will have to write off as not strictly accurate hosts of things that we ordinarily think are true. 'I remember when I was two inches taller than I am now.' That seems all right, but Descartes must say that it is not strictly true: what remembers is a mind; what has a height is a body; and the statement can be rescued only by taking its 'I was' and 'I am' as a vulgar shorthand for 'my body was (is)'. Though uncomfortable, this is not fatal unless Descartes absolutely needs men in his metaphysic – which I suspect he does not. (Bennett, J., 2001, p. 83)

This will be interesting to keep in mind in the investigation of the external world. Hence his body is external, and it is not Descartes, though it is somehow under his control. I don't believe Descartes was this thinking thing he claims, but that his thinking part was one of his domains. I don't see humans as being their thoughts and having bodies, though I do not have evidence for what the cause of the thought is. My last objection to his premises are: that the sceptic "rules" are quite bizarre. When applying such doubt in the search of the true, I can no longer prove that i.e. I am not you. If I cannot trust I am not in a dream, I could not even trust I am not a machine. But this very riddance of all certain things is like giving the ego metaphysical wings. It is close to madness, I do believe, but I admire Descartes for what he achieved.

Evidence of the External World

There is a distinction between the knowledge we can attain: (I) the certain kind, unchallenged by all thought, and the (II) probable kind which is more constrained. Descartes' evidence here is of the latter kind, and is induced from his understanding of imagination in the mind. For where understanding itself operates beyond the corporeal, the imagination makes use of body to envisage the ideal. Since Descartes can think of no opposing theory to this, he concludes that to imagine, a body must exist. A body is extended, a corporeal thing, therefore this is evidence for the external world it is in. He then returns to the mode of thinking that he calls "to sense", though the previous information given through the senses is dispensed:

In addition to pain and pleasure, I also sensed within me hunger, thirst, and other such appetites, as well as certain bodily tendencies toward mirth, sadness, anger, and other such affects. And externally, besides the extension, shapes, and motions of bodies, I also sensed their hardness, heat, and other tactile qualities. I also sensed light, colors, odors, tastes, and sounds, on the basis of whose variety I distinguished the sky, the earth, the seas, and the other bodies, one from the other. Now given the ideas of all these qualities that presented themselves to my thought, and which were all that I properly and immediately sensed, still it was surely not without reason that I thought I sensed things that were manifestly different from my thought, namely, the bodies from which these ideas proceeded. For I knew by experience that these ideas came upon me utterly without my consent, to the extent that, wish as I may, I could not sense any objects unless it was present to a sense organ. Nor could I fail to sense it when it was present. (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation Six, p. 62-63)

Descartes admits that it seems impossible for this sensual information to be coming from within.

He writes "[...] the remaining alternative was that they came from other things." (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation Six, p. 63) To be able to attain more knowledge of the external world, Descartes must again sense, but not undeterred. From these sensuous perceptions his mind receives different impressions about varieties of material things that in mind occurs as renderings. In the mind the rendering of extended things can be distinct ideas from remembering. In his mind he finds evidence of Gods existence distinct and clear; for as he is in this non-extended state, God must also be there:

In fact the Idea I clearly have of the human mind – insofar as it is a thinking thing, not extended in length, breadth or depth, and having nothing else from the body – is far more distinct than the idea of any corporeal thing. And when I take note of the fact that I doubt, or that I am a thing that is incomplete and dependent, there comes to mind a clear and distinct idea of a being that is independent and complete, that is, an idea of God. And from the mere fact that such an idea is in me, or that I who have this idea exist, I draw the obvious conclusion that God also exists, and that my existence depends entirely upon him at each and every moment. (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation Four, p. 54)

Pleasure and pain originates from the external world as well, and as it is sensed by the body, it becomes a sensation in the mind that the mind cannot dispel. Descartes says that this kind of reaction is a natural way to provoke a bodily action, i.e. when the throat is experiencing dryness, it is a natural need for hydration behind this. And when the thinking thing experiences thirst, despite not being extended – it now somehow knows that a drink is recommended. This is how the mind have knowledge of the bodily needs, it tells what to avoid and what to seek. For Descartes, this is evidence of God's perfection – there is no better way He could have made this connection:

[S]ince any given motion occurring in that part of the brain immediately affecting the mind produces but one sensation in it, I can think of no better arrangement than that it produces the one sensation that, of all the ones it is able to produce, is most especially and most often conducive to the maintenance of a healthy man. Moreover, experience shows that all the sensations bestowed on us by nature are like this. Hence there is absolutely nothing to be found in them that does not bear witness to God's power and goodness. (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation Six, p. 67)

At the end of meditation six, his hyperbolic doubt gets dismissed (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation Six, p. 68). He no longer fears the falseness of his senses, and he comes back to the world from behind his sceptic fences. It now seems that this project indeed has brought some fruits – at least one (to him) strong, incontestable truth. It seemed necessary for him to go this far, in light of his doubt being quite bizarre. He admits his skeptic premises being overly extreme, and distinguish the awaken state from being in a dream:

For now I notice that there is a considerable difference between those two; dreams are never joined by the memory with all the other actions of life, as is the case when one is awake. For surely, if, while I am awake, someone were suddenly to appear to me and then immediately disappear, as occurs in dreams, so that I see neither where he came from nor where he went, it is not without reason that I would judge him to be a ghost or a phantom conjured up in my brain, rather than a true man. But when these things happen, and I notice distinctly where they come from, where they are now, and when they come to me, and when I connect my perception of them without interruption with the whole rest of my life, I am clearly certain that these perceptions have happened to me not while I was dreaming but while I was awake. (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation Six, p. 68)

Discussion

Although such a long time since Descartes' meditations, his work still offers body/mind-implications. We do have knowledge that Descartes didn't know, but we still have a very long way to go. Many of these questions stands unanswered today, or, they have been answered in an insufficient way: What is consciousness really about? And how can we use his methodological doubt? Is there anything more to the human mind, than scientific research can let us find? You will not find answers to these questions in my essay. They are too big to answer in such an excess way. One thing I have learned from Descartes meditations is to question my knowledge and sensuous sensations. Another is that our minds are restricted – not all of the mysteries can be depicted. A third lesson learned is the one about dreams: I know I am awake, or, so it seems? We cannot really know anything for sure, except our subjective existence, so I have learned. Personally I have not changed my opinion about the external world from this, and I am still (happily) quite sure that it actually exists. But what Descartes has surely reminded me of, is that we see the world through our egos a lot. Descartes' view in this work, is the one from inside out. It is the best suited view for this methodological doubt. It is the ego's exploration of itself – but also with God the creator he dealt. Whether God as he claims is an actual being, I make no effort myself to try to believe in. When it comes to his arguments about the perfection of God, I must admit I have not interrogated them hard. To prove them is not necessary for the topic, for the time being I consider myself an agnostic. What regards the mind beyond body-thesis, I present here a poem to show what my belief is:

https://steemit.com/escape/@jonasontheroof/sleep-paralysis-ego-trap-what

I hope this little essay have confused you and amused you. I guess that this assignment is not the kind that you are used to. I have natural reasons to not go as deep as Descartes in these investigations – but one day I too may have to "raze everything to the ground and begin again from the original foundations." (Ariew, R. & Watkins, E., 2009, Meditation One, p. 40) We have much to do fully understand the human mind. From the inside out, and outside in and through the pineal gland. I think: Must philosophy and poetry go hand in hand – and put down in words those mysteries we not yet understand.

LITERATURE:

Ariew, R. & Watkins, E. (2009). Modern Philosophy: an Anthology of Primary Sources. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing (2nd ed.)

Bennett, J. (2001). Learning from Six Philosophers (vol.1). Oxford: Clarendon Press

Gazzaniga, M. S. (1995). Principles of Human Brain Organization Derived From Split-Brain Studies. Neuron (vol.14), February 1995, p. 217-228. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0896627395902805/pdf?md5=117b4e05edaa044f7da8d8545636f460&pid=1-s2.0-0896627395902805-main.pdf

Hari, R. & Lounasmaa, O. V. (2000). Neuromagnetism: tracking the dynamics of the brain. Physics World, May 2000, p. 33-38. Available from (via UiO vpn-login): https://vpn1.uio.no/+CSCO+00756767633A2F2F766263667076726170722E7662632E626574++/article/10.1088/2058-7058/13/5/30/pdf

I don't really know how to comment an essay.

I think it's tragic, that there are only few upvotes and no constructive comments.

Should you have included 'Descartes' in the title ? (I think so)

Would any of his 'Meditations' made have any sense without the 'God' part ? - I don't think so; it's crucial.

If he hadn't started on the pretense that there is only one truth, it would have ended in desaster.

The only reason that dismissing everything external doesn't lead him to madness, is this underlying 'truth' he believes in -he personifies it to 'God'.

I will write an essay about it.

Good post! In school I even didn’t know how to write an averege essay, always asked for help guys like this http://enhelp.org/