Read the introduction to this series here.

Book I, Part I, Chapter I, Section 1: Commodities

Marx begins his magnum opus with an analysis of capital. After all, one can't discuss capitalism without considering capital. Commodities are the first topic of discussion, and his initial definition of commodities is perfectly fine as far as I can tell.

A commodity is, in the first place, an object outside us, a thing that by its properties satisfies human wants of some sort or another. The nature of such wants, whether, for instance, they spring from the stomach or from fancy, makes no difference. Neither are we here concerned to know how the object satisfies these rants, whether directly as a means of subsistence, or indirectly as a means of production.

All well and good so far. I am sure economists might find ways to quibble already, but the opening seems quite sound to me.

Marx continues on to cover quantity and quality, convention, and his concept of use-value. He says the use-value of a commodity is independent of the labor used to appropriate it. So far, so good, but his use of the word, "value," at least in English, strikes me as a potential point of confusion already.

Intrinsic material properties, including scarcity, inform the individual of its suitability for any given purpose. The value of that purpose, however, is based on the subjective perception of the individual. As more people participate in a market of free trade, an equilibrium market price tends to be discovered through the process of multiple exchanges, but these prices do not represent a perpetual equilibrium or a value equivalence between goods. By this analysis, material properties, value, and price are interconnected, but not in the sort of relationship Marx seems to be arguing.

In the following passage where Marx goes on at length about the exchange value for wheat versus blacking, silk, gold, etc. Marx says,

...[T]he valid exchange values of a given commodity express something equal...

Then, he describes a mathematical and geometric equivalence theory of value between goods, insisting,

...[T]he exchange values of commodities must be capable of being expressed in terms of something common to them all...

Thus, after a clumsy attempt to define value in use and trade, he concludes that the only common property of all goods is being products of labor in the abstract. He argues that,

A use-value, or useful article, therefore, has value only because human labor in the abstract has been embodied or materialised in it.

I do give him credit for observing that slow labor does not add value. However, he continues to insist that there is some sort of "homogeneous human labor," calculable on the societal level. He then argues that commodities with the same labor and time expenditures are of equal value.

This is a dreadfully confused perspective that will doubtless pervade the rest of the work. It puts the cart before the horse. People do not value things because of the labor and time put into them, people put time and labor toward things they value, or have reason to believe other market actors will value. Exchange does not denote equivalence in a zero-sum game, but rather mutual benefit.

Any flaws in Marx's analysis of labor and value can only distort any arguments using this theory as a premise, and his next argument builds on it directly.

In general, the greater the productiveness of labor, the less is the labor-time required for the production of an article, the less is the amount of labor crystallised in that article, and the less is its value...

It is true that reducing the labor costs of production tends to result in lower prices, but this has no impact on the intrinsic properties of the commodities in question. Price and value are still distinct concepts,and changes in production processes and prices result in a complex interaction of numerous factors.

Carl Menger's work on marginal utility was still a few years from publication when Marx published the first part of Das Kapital, but Menger didn't invent the idea, he refined ideas that the economics community had been exploring for some time. Even though Marx sidesteps the worst caricatures of the labor theory of value, his insistence that labor is the foundation of value is still based on an obsolete idea, and his references to Adam Smith (1723-1790) and Nicholas Barbon (c.1640-1698) only offer the barest suggestion he had any understanding of outside economic thought thus far.

Still, in all fairness, this is just the first section of the first chapter of the first book in a very long work. I am reading a translation, so the potential for miscommunication arises there, too. While I find the reasoning here at the start deeply flawed, I plan to persevere while I can. If you see something I overlooked, wish to add commentary of your own, or have criticisms of my criticism, feel free to comment below.

I'm finding the quoted writing hard to read, although that could be due to translation. Was it translated soon after the original was written, do you know?

Your own thoughts bring an interesting perspective along side it. I hope to remember to check back in and read more.

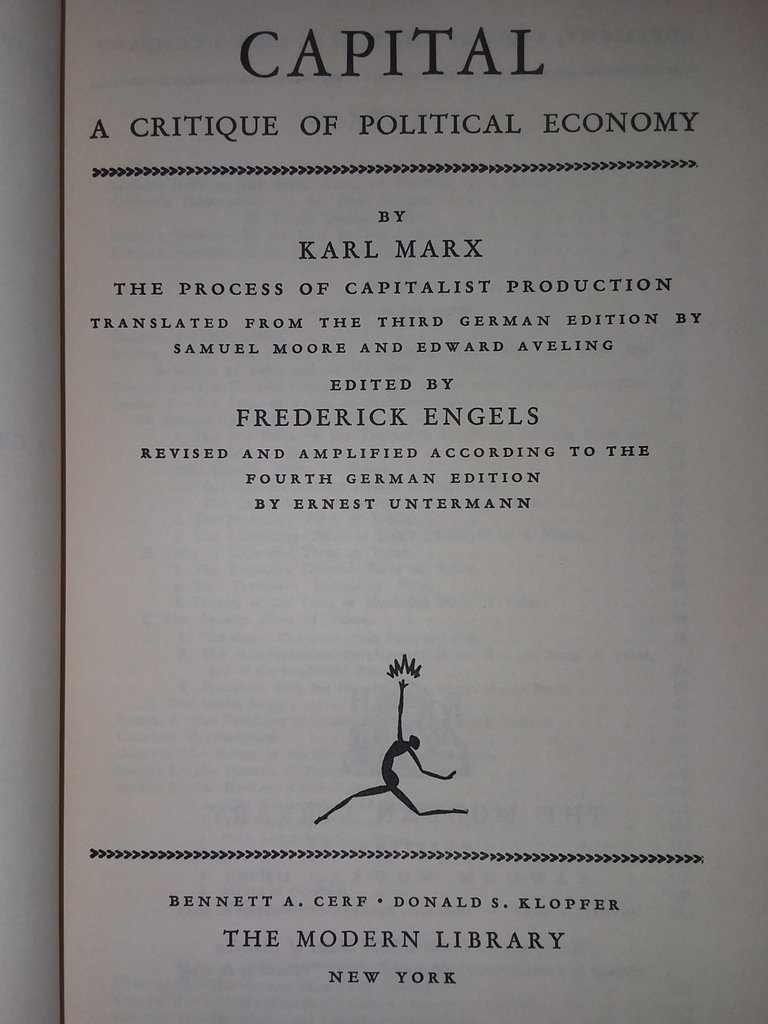

If memory serves, Marx published Book I in the 1860s, and died a few years later. Engels edited Marx's notes and published the entirety in the 1870s. This edition is a 1906 printing of an earlier English translation. I could wade through the assorted prefaces and forwards for more info later. My intro post has a link to a digital version though, if you want to check for yourself.

Marx's concepts are built on such flimsy, illogical, foundations that most 5 year old kids would question the veracity of the arguments.

...And then there are the lefties that swallow all the guff, and hail him as a genius - to illustrate just how retarded they must be...lol.

I can see the appeal of his arguments, but the reasoning thus far leaves me underwhelmed. I have started reading ahead to Section 2, and there seems little promise of improvement.

..you are destined to be feeling.....erm....bereft...lol

Have you read it yourself? I can't say I really know much about his work, just know the name.

yup - and the com manifesto - and parts of wage labor and capital - quite a few years ago though.

He really wasn't that intellectually bright, but quite persuasive in writing style - IF you buy into the foundational premises (which are bollocks).

Utopian ideas and ideals are often nice, but when you get down to reality they don't work and that old saying of the road to hell being paved with good intentions makes so much sense.

Except the intentions are not good - the intentions are control over others.

Fear is the unconscious motivator, not some apparent 'conscious benevolence'.

It always bugged me how capitalist right voting democrat factory owners use a communistic regime to rule over the workplace . For they always keep the extra profit made by faster working , but just as good or even better quality making , employees .

When trying to argue the fact that a 15 year old , that makes product's better as a 40 old year old , should earn more pay , you will get slapped in the face with Marxist bullshit that ends any logic .

Egg and chicken loops , like a horse behind the cart ;-)

Piece work > hourly pay for many jobs. When I did yard work, I preferred a lump sum for the job instead of an hourly pay rate.