Many of you followed me as I wrote chapter after chapter of "Katharsis," and now I'm happy to present you with the fruits of that labor. I felt I was getting a little disjointed and aimless with the novel I was writing, and I decided it was best to give up on that draft. However, I've edited down the middle portion of what I wrote, focusing on one plot in particular, and it makes for a complete and compelling story. I have converted it into a stand-alone novella that I will publish on Amazon in the coming months, but I thought the Steemit community ought to be the first to read it. You guys gave me the motivation to write it, so I hope you'll enjoy what I've written! It's a tad long to post it in two parts, but I feel it would be disingenuous to milk it into a bunch of separate posts that some of you might have already seen...

Anyway, enjoy, and tell me what you think in the comments!

.

.

.

.

Buddy

81 1/2 Rutledge was the second and third floor in the back of a two hundred year old mansion by Colonial Lake. The front of the building was flat stone and imposing, coming right up to the sidewalk, with giant wooden doors and a metal plaque beside them to commemorate its historical significance. The part I was to move into was a wooden extension built a little over a hundred years ago, and to get to it you had to walk down a long driveway of cracked pavement, then climb a flight of dilapidated wooden stairs that threatened to collapse with every step. It was 99 degrees in Charleston the day I arrived, and I hadn’t noticed during my visit a few months earlier that there was no central AC in the house, just a few plastic AC units stationed here and there, hardly doing anything.

The heat was oppressive and unsettling, but it was not as unsettling as the presence of an unexpected fourth roommate named Buddy, a thirty-four year old alcoholic and cokehead who greeted me at the top of the stairs, cigarette in his mouth and beer in his hand at one in the afternoon. He had a sort of glazed look in his eye that I would later come to understand as a mixture of depression and inebriation, but even in that first glance I had the weird feeling there was someone else in him, looking out as if through a cracked and dusty pane of glass. He shook my hand and introduced himself, then he helped me carry the first of my bags into the living room. With the front door still open and the beer still in his hand he sat down on the couch and took a square mirror from the cushion beside him. Without bothering to roll up a dollar bill he pressed his bearded face to the mirror and snorted a sizable line of white powder, then he looked up at me with white specks all over his beard and held the mirror out to me.

I waved him off and said, “Nah, I’m gonna keep unpacking. Thank you, though.”

“Suit yourself,” he said. He put his face down and did the other line.

The room I was to inhabit, formerly Kat’s, was on the other side of the wall that faced the front door. I learned later that the wall had only been added a few years prior. My room and the living room had once been one room that doubled as a sort of speakeasy, a place where Charleston’s inbred elite would come to drink and do blow after the legal bars all closed at 2 AM. Mr. Braddon’s son Matthew was living in the house at that time, and he was the bar manager, bartender, and chief coke dealer. When the cops finally stopped turning a blind eye and shut the whole thing down, Mr. Braddon kicked Matthew and his buddies out of the house, built the wall through the middle of the living room, and started renting the place out to college kids.

The side that became my room was remarkable only in its gloominess. Dark wood floors with paint stains, cobweb covered windows with no blinds, a fireplace between the windows, a brass chandelier with candelabra lightbulbs, all wrapped in dark maroon walls that looked like they’d been painted a hundred different times by a series of increasingly inept or indifferent painters. There were sloppy patch jobs marring every smooth surface, there was a noticeable gap between the wall paint and the white molding of the ceiling and floor, and the paint was peeling and chipping from just about everywhere, each gap revealing a different layer of color from years past.

I started piling my things in the middle of the floor, making trips back and forth to my car which was still parked in the driveway, radiating heat. At some point Buddy made his way into my room, fresh beer in hand, and started rummaging through the cardboard box of books that’d I’d set down near the fireplace. He took out a grey paperback called I am the Cheese, laughed at the title, then he took out a little plastic baggy of cocaine from his pocket and started making himself more lines on the surface of the book, which he had set down on the mantel over the fireplace.

“I already know I’m gonna like you,” he said.

I laughed half-heartedly and said, “Likewise.”

I inflated an old aero bed against the wall that ran along the hallway, and I piled the remainder of my luggage in the corner of the room in front of a locked door I initially thought was a closet. It really led to the laundry room, which was the connecting point between the kitchen, the bathroom, and Buddy’s room in the far back of the house.

I left Buddy by the fireplace still drinking and doing lines, and I went up to the third floor to see if the other roommates were home. I found Robbie playing Fortnite in his room. He offered me a hit of his bong and I was foolish enough to accept the offer. A few minutes later my anxiety was pumping in a big way, and I had to retreat back to my room on the pretense of being tired before the panic attack could work itself up into full force.

Thankfully, Buddy was gone when I got down there, and I collapsed onto the Aero bed and began the all-too-familiar effort of trying to calm down and not die of a heart attack. The bed rocked around with the slightest movement, like laying on JELLO, and in my panic-stricken state it seemed the bed was the physical embodiment of a metaphor for my life. I had lost all foundation and stability, and my attempt at reclaiming that foundation by returning to Charleston was already having the opposite effect. I missed my real bed, my parents, my dogs, my air-conditioning. I had been a fool to think I could come here and become the person I used to be or live the life I used to live. My parents were right: there was nothing left for me here.

Like all panic attacks, this one eventually passed and gave way to relief. Since I had begun my new life with failure and resignation, I gradually decided things could only get better from there, which was true, more or less.

Hunter got me a job at the deli by his house on Dewey Street, and after work we would go to his place to barbecue or go to the bar at the end of the street, Faculty Lounge, to drink and play pool. His paranoia about the cops and gang violence seemed to have subsided, and it was encouraging to see that he was genuinely happy to have me back in the city. The sincerity of his friendship was enough for me to feel like maybe returning to Charleston had been the right choice after all.

Back at the house, Robbie and I were butting heads over small things: my contributions to the dishes in the sink, my culpability in our outrageous Comcast data charges, my friendliness toward our downstairs neighbor Sharon, who he used to have a thing with. We might have strangled each other in those first few weeks if not for Joe and Darian around to break the tension. The four of us started making regular trips to the tennis courts by Colonial Lake, and while we were all far too competitive we enjoyed it anyway. Despite drinking vodka mixed drinks every time we played, I treated every match, every game, and every point as if it were the U.S. Open, and I kept track in my head of how many matches I won in a row, as if this was an objective barometer for life progress.

There was a pleasant irony in the fact that each time we walked to the courts we walked past Nelson Hollings’ old apartment, the one I’d stayed in six years earlier on my first visit to Charleston, now known only as the “trap house” after eight people got arrested there in an FBI drug raid. The story had been all over the news, and some Post and Courier reporter won a Pulitzer for his article on it. It felt I had become a part of the city’s history in some obscure way, and now that I was back I was once again an actor in its future.

As I fell back into a comfortable routine— working at the deli, playing tennis with my roommates, and drinking every night with Hunter— my anxiety gradually subsided. I got back on Tinder and had some relative success (no humiliating failures at least), and I started smoking weed again in tiny amounts without having any panic attacks. I still had no idea what I wanted to do with my life or how I would accomplish it, but it seemed this effort to find myself or fix myself might, by baby steps at least, be paying off.

But at the same time that my own life was incrementally improving, someone else’s was approaching an irreversible nosedive. In those first few weeks that I knew him, Buddy kept to himself mostly. Joe, Darian, and Robbie had been avoiding him since before I moved in, and, as Buddy quickly began to detect the same energy from me, he stopped barging into my room to do cocaine, a habit which I failed to realize was his unconventional way of offering friendship. He had an obese girlfriend named Caroline, and whenever she was over they’d stay locked up in his room in the back of the house doing things no one wanted to imagine. Eventually he started to stay in his room even when Caroline wasn’t there. The only times he ventured out, that I can recall, were his frequent trips to the bathroom and refrigerator and his daily pilgrimage to the living room to do cocaine on the couch. He never went to the third floor without a good reason, he never went to play tennis, and as far as I could tell he never left the house at all. If he needed food, he just ordered delivery or took someone else’s out of the refrigerator.

He became a frequent topic of conversation, all of us telling our latest Buddy sightings as if he were last of some bumbling but exotic species of animal. The commentary on this peculiar creature always came back to one rhetorical question, which shocked me the first time I heard it: “Can you believe he has a five year old daughter somewhere?” Supposedly, he was a father to a daughter none of us had ever seen.

There were many things I didn’t know about Buddy until much later, and much more that I’ll never know. The Buddy that I saw was the tip of an iceberg floating in and made from the murkiest water imaginable. There were plenty of good things about him that I never got to see myself and couldn’t imagine being true. Joe and Darian swore he had an angelic voice, that he used to be an opera singer and with one note he could bring a grown man to tears. At the same time they also swore he had “the eyes of a man who’s had a dick in his mouth,” that one look in his eyes and you could see the muddled shame of having sucked someone off at some point. Anyway, it was clear that there was more going on with him than I would ever know.

I saw so little of Buddy that I didn’t even know he had a job until the day they fired him, which was also the day he started doing Katharax. Buddy had been working as a waiter at the Bubba Gump Shrimp Co. on South Market Street. From what I’m told, he started regularly coming in to work drunk or hungover, and costumers started to complain that he was forgetful and rude. Instead of firing him, the management moved him to bartender. As a bartender, Buddy started drinking on the job to the point of slurring his words, messing up orders, and, on at least one occasion, throwing up in the trashcan behind the bar. His manager was a friend of his and didn’t really want to fire him, so he pulled Buddy aside one day and gave him a stern talking to, telling him he needed to get help and that he’d lose his job if kept up this sort of behavior. Buddy told him to fuck off, then he skipped work the following day. And the day after that. The day after that, Buddy got a text message from his manager friend. The text said, “I’m sorry to say this but you’ve been fired. There was only so much I could do. Get some help, sober up, and I can help you get your job back when you’re ready.”

Buddy didn’t handle the news well. I knew something was wrong when I woke up to the sound of glass breaking in the kitchen, followed immediately by a howl of either pain or frustration. An hour later when I walked down the hallway to go to the bathroom, I saw Buddy standing in front of the open refrigerator, chugging with abandon directly from my carton of milk. He belched, wiped some of the milk from his beard, then looked over at me vacantly and grumbled, “Oh, hey,” his voice sounding, to my mind at least, distinctly like an impression of Buffalo Bob from the film Silence of the Lambs. I was about to tell him to use a cup next time he wanted to take some of my milk, but as I opened my mouth to speak I saw that there was blood all over his hand— the same hand that was clutching the carton— and his bare feet were surrounded by shards of glass. I decided not to say anything about the milk, and I decided to use the third floor bathroom instead of walking past him.

Fifteen minutes later I was smoking a cigarette on the third floor balcony and Buddy came staggering out and asked me if I could drive. It sounded like he was asking if I knew how to drive or was physically capable of driving, though it was obvious that he would follow up by asking me to drive him somewhere, so I cut to the chase and said, “Yeah, where you trying to go?”

He said, “Need to go to a friend’s place ’n pick somethin’ up, an if you cou’n’t tell I been drinkin’.”

I rarely ever say no to someone when they ask a favor of me, even when I have absolutely no desire to help them. I regularly turn people down when they ask me if I want to hang out or something like that, but with legitimate requests for help I always find myself saying yes, then regretting my spinelessness forever after. So, in keeping with this character flaw, I reluctantly said, “Okay, now where is the friend’s place you’re trying to go?”

The friend’s place was in North Charleston, about twenty minutes away via the interstate. It was a long and somewhat uncomfortable ride, lots of traffic and Buddy was smoking cigarettes the whole way, blowing the smoke straight at me instead of out the cracked window. He was mumbling and rambling, mostly to himself, about how pissed off he was at getting unjustly fired from Bubba Gump. “I mean, I did stuff I shou’n’t'ah done, but I work there for, shit, three years…? And then to— they thruh me out like I was whad, the trash?”

“That’s fucked up, man,” I kept saying over and over.

Eventually I got around to asking him what he needed to go to the friend’s place for, and he answered simply “drugs.”

“What kinda drugs?”

“Diff’ren stuff,” he said. “I’ll gi’ yuh some fer drivin’ me.”

The place we were going was in a decidedly bad neighborhood, and I was simultaneously alarmed and relieved to see that there was a patrol car posted about a half a block away from where I had chosen to park. Alarmed, because it meant the cop might be watching the very house Buddy was going into and that I might get arrested by association— and relieved, because it meant I was less likely to get robbed or arbitrarily murdered, which seemed to happen fairly often in this part of town.

Buddy opened his door and said, “Wait here.”

I said, “That sounds ideal. I would feel kinda—“ but he was already out. He shut the door before I could finish what I was saying.

I waited there for a long five minutes, listening to my hip hop playlist with the volume really low, trying to bob my head in a lighthearted, non-threatening manner as I looked back and forth between the cop in the rearview mirror and the run-down, paintless house that Buddy’d walked into.

Buddy finally came ambling out, stumbled into a bush, regained his balance, then yanked open my door and heaved himself down into the seat. He slammed closed the door and before I could ask him how it went he’d already pulled a ziplock bag out of his pocket and said, “Look at dat, ha!” proud as I imagined a father might be watching their child walk for the first time. He studied the bag in the light for a moment, then he held it out to me to look at. I didn’t want to look because I was still worried about the cop, but I saw that the sandwich bag was full of white, M&M-looking pills with KX printed on them— Katharax— and in the midst of the forty or fifty kathies was a plastic-wrapped cocaine rock that probably weighed at least a quarter ounce.

“That’s very nice,” I said as I put the car into drive. “How long will that last you?”

I pulled into the street and started us on our way, checking the mirror to see if the cop was reacting at all, and I noticed in my peripheral vision that Buddy was pouting his lip and inspecting the bag, calculating. I wondered then and still wonder now what that mathematical function must have looked like in his mind. What were the variables? Did they include blackouts, hangovers, irresistible cravings, tolerance, the risk of an overdose? Or did he have a more positive outlook, comparing all the fun he’d be having to the number of grams of fun he held in the bag? In any case, he looked at the bag with a thoughtful expression for several seconds, and just when I thought that he had forgotten the question he lifted his ass from the seat, crammed the bag into his pocket, and casually said, “Few days,” leaving me to reverse calculate the extraordinary daily intake this estimate implied.

When we got back to the house, I went to the top floor again to look for Joe or Darian, but neither of them were home. I went out to the porch to smoke another cigarette, and, to my surprise, Buddy followed me out there, announcing his presence with the pop and fizz of a beer can. We were now standing in the exact same places we had been standing an hour before, but now the atmosphere was suffused with tension, as if the sack of Katharax and cocaine had set up a row of dominoes that would inevitably be knocked over.

Partly because I was worried about him and partly because I was worried his self-destructive behavior would lead to more broken glasses and violent outbursts, I decided to give Buddy the same lecture I was prone to give anyone who expressed interest in Katharax. I told him about the lasting neurological disorders it caused. I told him about it’s status as a top 5 addictive substance, one of the only drugs where the withdrawals were bad enough to kill you. I told him about the overdose statistics— the highest of any prescription drug in the United States. I even gave him my personal opinion on its efficacy as a treatment for anxiety and PTSD.

I must have talked for ten minutes straight, Buddy not refuting or commenting on anything, just listening politely and smoking back to back cigarettes after he finished the beer. When I finally finished my spiel, there was a momentary pause as he waited to see if I was going to continue on talking, and when he saw that I really was finished he said, “Yeah, but I like Kathies, and I can’t die.”

“You can’t die?”

He nodded and smiled. “Used to do five kathies a day. Quit cold turkey when I felt like it. An’ I know I can’t die cause one time— I was thirteen— stole my daddy’s truck, went drivin’ down this road, wrecked it real hard into a tree. Musta been going like fifty or so. Went through the windshield— wasn’t wearin’ a seatbelt, so I go through the windshield bout twenty yards into this field. I was legally dead for fifteen, twenty minutes or so ‘fore the ambulance people showed up and started my heart back up.”

“Jesus.”

“Yeah, they said it was a miracle, and that’s how I know I can’t die. I got Jesus lookin’ out for me, huh huh huh.”

That was really what his laugh sounded like— huh, huh, huh— completely monotone, like he was reading his laugh off this page. I laughed too, probably as inauthentically as he had, and said, “Fair enough, man, just try not to make Jesus work any harder than he already has to.”

Things went downhill for Buddy quickly after that, though it was hard to notice because he spent so much time locked away in his room and I spent so much time trying to avoid him. The only signs that something was wrong were fairly indirect: He stopped making his daily pilgrimage to the living room to do cocaine, a bottle of vodka I’d been keeping in the freezer somehow froze solid, I went to the bathroom and walked in on Caroline crying in front of the mirror, and one afternoon I crossed paths with Buddy while doing my laundry and he said something to me that came out as guttural nonsense, like a string of words a Neanderthal might have said before the dawn of sophisticated language.

And then there were the roaches. This final clue that something was wrong would have probably been the most disturbing if it hadn’t also been the most indirect. At the time I never even considered that they could be related to Buddy or his drug abuse. From the day I moved in I had been seeing the little fuckers, “german” roaches they called them, a quarter the size of a cockroach, that would show up in the kitchen or the bathroom then dart behind some surface as soon as you noticed them. I would see a handful of them every day, but they tended to hang out near the kitchen, and the sink was always so dirty it seemed obvious that they were just living off whatever scraps we left out for them. Their numbers gradually and almost imperceptibly increased over those first few weeks that I lived there, but I didn’t mind them any more than my other roommates until their population suddenly exploded in that last week of June.

Overnight they had taken over the kitchen completely, so many of them that I’d see at least five any given time I went to the fridge or walked through to take a piss. Any time I opened a cabinet or drawer there would be three or four of them scattering like I’d caught them smoking grass in an alley. Soon they had conquered not only the kitchen but the bathroom and the laundry room too, and even though they had plenty to live off of with the sink and the dishes and a floor smattered with air-dried beer spills and tomato sauce, they had no intentions of ending their empire there, and by the right of their manifest destiny they sought to overspread and possess the whole continent providence had offered them.

They started coming in beneath that locked door which led to the laundry room, threading their way through the interstices of my luggage and then spreading out into the disarray of my floor like post-apocalyptic scavengers entering a ruined city. There were towers of books all over the place in little stacks, the humming AC unit, clothes in haphazard piles, bags that still hadn’t been unpacked or put away, a variety of art supplies strewn beneath a window, and even a few cobweb-covered shutters that Sharon had left in the corner because she hated to throw things away. The roaches seemed to like the books the most, and soon I couldn’t pick up anything to read without a roach or two scurrying out. On the covers of all the books I started finding thick speckles of brown, like tree sap, that could have been insect vomit or insect piss but was regardless some form of insect bodily fluid that would stick to my fingers. To make matters worse, the roaches were the exact shade of brown as the wood floor, so even when I made an attempt at organizing and cleaning up I could still never be sure how many were around me at any given time, and after I started finding them in bed with me, crawling over me as I slept, I entered a constant state of paranoia. I’d see them everywhere, even in the places they weren’t. My eyes started to detect tiny, flitting movements that would sometimes be roaches and sometimes be hallucinations, and even in my car or in Hunter’s obsessively clean house I’d find myself flinching at the sight of imaginary insects.

Of course, I was all the while doing everything I could to kill the little bastards, and as they started to encroach upon the third floor the other roommates also joined the resistance. We set up poison traps all over the place and bought cans of Raid. The Raid seemed like a particularly unpleasant way for them to die— in my mind they were like little people I was hitting with mustard gas, and they’d run around frantically until they fell over twitching like crazy— so I made sure to use the Raid as often as possible, and I started leaving roach corpses in conspicuous places in order to strike fear into their comrades. Over a few days I perpetrated a small holocaust, but no matter how many I killed they kept coming back, more of them each time, the borders of their empire now encompassing the whole house, even Sharon’s apartment downstairs.

I had become so preoccupied with thinking about the roaches that I all but forgot about Buddy until one day there was a quiet knock at the front door, and when I got there and opened it I found a squat, fifty-something year old lady with a bowl cut looking up at me with a nervous smile.

“Hi,” she said. “Is Buddy home? I’m his mother.”

“Oh, hello!” I cried with a false enthusiasm, masking my surprise and alarm as I tried to block her line of sight into the living room which was littered with roach-filled beer cans, discarded plates, and the brown guts of cigars that had been turned into blunt wraps by Joe and Darian. “Let me go see if I can find him,” I said, then I closed the door on her as politely as I could.

When I got to the end of the hall and passed through the kitchen I saw that the door to Buddy’s room was wide open. I had never seen the inside of his room before, but all I could see now was Buddy’s bed just in front of the doorway. On top of it was Buddy sprawled face down over the covers, completely naked. My immediate impression as that he was dead, overdosed, and now I would have to tell his mom that her son was dead, but when I hissed BUDDY at him he started to shift around, and when I did it again he turned his head toward me and grumbled “What?” with apparent irritation.

I said, “Buddy, your mom’s outside looking for you. She knows you’re here. You need to get dressed and come out front.”

He made a noise like “Mraaghhh” then muttered, “I’ll be there in a minute.”

I went back up front and informed his mother the he would be there in a minute. It occurred to me then that I didn’t know what to call her— Mrs…?— because I didn’t know Buddy’s last name. He was just Buddy. I said one more time that he’d be there in just a minute, then I made a half-smile and closed the door again.

Ten minutes later Buddy still hadn’t gone to the door, and his mother started knocking again, louder, and calling, “Buddy? Buddy are you okay?”

I went back to Buddy’s room and found him in the exact same position I had left him ten minutes earlier. I said, “Buddy, get the fuck up! Your mom’s waiting on you! She’s been out there for ten minutes!”

“Alright fine!” he yelled back, then he rolled from the bed with a moan, completely indifferent to the fact that I had a direct line of sight to his junk; though, for my part, I was more disturbed by the seamless transition between his afro-like pubic hair into his curly belly and chest hair, which now just seemed like an extension of the pubes. I didn’t want to be standing there any longer, and I was now confident that he wouldn’t fall back asleep, so I scurried down the hallway again and opened the door to his teary-eyed mother who was in the middle of dialing someone on the cellphone.

“Is he okay?” she asked.

I said, “Yes, yes, of course. He’ll be here in just a minute. I’ll go hurry him up.” And thankfully, just as I was about to close the door on her a third time, Buddy emerged from the hallway with clothes on, and I said, “Ah! Here he is now! I’ll leave you two to it!”

I hoped that that the visit from his mother would be a wake up call for Buddy. She clearly knew that something was wrong with him, and she’d driven over an hour to come and check on him in person. The best thing would have been to drive him straight to a rehab center, but in their short meeting he must have told her he’d shape up, maybe yelled at her for intruding in his life, because an hour later he was walking back through that front door with a pissed off look on his face. He didn’t say anything to me or Darian— we were playing bumper pool but stopped to watch him— and he just continued right through the room, down the hallway, through the kitchen, then we heard his bedroom door slam closed behind him.

The next morning I woke up to an inhuman howl and a thunderous crash from the living room. I heard billiard balls hitting the floor and rolling into the thin wall of my bedroom. There was another tremendous thud as the bumper pool table toppled from its edge and settled upside down on the floor, then there was another yell, like a moan of agony, unmistakably Buddy, before something made of glass shattered against the other side of my wall and made me fear that this rage was in some way directed at me. I laid in bed listening to him until I heard him stomp his way past my door and down the hallway, smash something heavy in the kitchen (it was the toaster), then slam his bedroom door with a final scream of frustration. I ventured out to assess the damage and just outside my door I ran into Caroline, whose face was bleary and red from crying.

“What’s going on?” I asked. “Are you alright?”

“Take care of him,” she said, then she burst into tears and covered her face with her enormous hands. She said it again, this time muffled by the hands, then turned around and hurried away from me, into the living room and out the front door.

I went into the living room then to assess the damage. As expected, the bumper pool table was upside down, looking like an old fashioned candle-holder with its one leg as the candle, pointed up at the chandelier. Most of the balls were lined up against the wall to my room, and around them were shards of the cocaine mirror. The lamp was on the floor too with its shade off, the lightbulb still glowing a dusty yellow color. I picked up the lamp and set it back on its little plastic table next to a beer can with mold coming out of it and a cereal bowl filled with cigar tobacco and some sort of grease. The screw that held the shade in place was missing, so I just put the shade balanced on top and hoped that it wouldn’t fall off.

Picking up the bumper pool table was trickier. It was fairly large, heavy by my own standards, and if I put too much weight on its leg it might snap off from the base. I didn’t want Robbie to see it like that, though. It was worth the risk to try and put it back on its feet without any help, and luckily the leg held strong as I used all my strength to tip the thing onto its side then back into an upright position.

Just as I was putting the last of the balls back onto the table, Buddy came walking in slow and zombie-like, and he sat down heavily onto the wooden stool near the fireplace. He looked at me setting the balls on the table but didn’t say anything. The silence was more than just awkward— it was thoroughly unsettling. I was worried that anything I might say would trigger some sort of violent outburst, but the silence made me so nervous I felt I needed to say something, anything, to break the tension.

“Everything okay?” I finally blurted out. I qualified this question by then saying, “It sounded like you were upset this morning,” which was the understatement of the century.

As I was speaking I absent-mindedly rolled a ball to the other side of the table. He watched it thud against a bumper then settle in the corner.

“I’m gonna kill Robbie,” he said, so steadily and gravely that I knew immediately it wasn’t a figure of speech.

With a sort of mock-incredulity, meant to mask my very real trepidation, I said, “You’re going to kill Robbie? What’d he do this time?”

“Stole my drugs.”

“And you’re sure it was Robbie?”

He ignored my question and said, “I have a gun in muh room. Pistol. When Robbie gets home I’m gonna to shoot‘m in his fuckin’ face.”

Christ Almighty, I thought. The fuck do I say to that?

“Please don’t kill him,” I said. “Pleease don’t kill him. I know he can be an asshole, but don’t kill him. As a favor for me, don’t. That would be a nightmare. And besides, you’ll be ruining your own life at the same time you’re ending his.”

Buddy was still staring at that same red ball that had settled in the corner. He said, “I’mma kill myself too, when I’m done. I’ll shoot Robbie in that snide lil face uh his, then I’ll put the barrel in my mouth and—” he used his middle and index fingers to pantomime the handgun pointing at the roof of his mouth— “click.” His thumb moved to indicate the hammer drop of the firing gun, but he didn’t move his head or do any cartoonish impressions of his brains flying out, he just withdrew the finger-barrel from his mouth with an inscrutable look on his face then placed his hands palms-down on the table.

He said, “Thank you, but I’ve made up my mind.”

TO BE CONTINUED

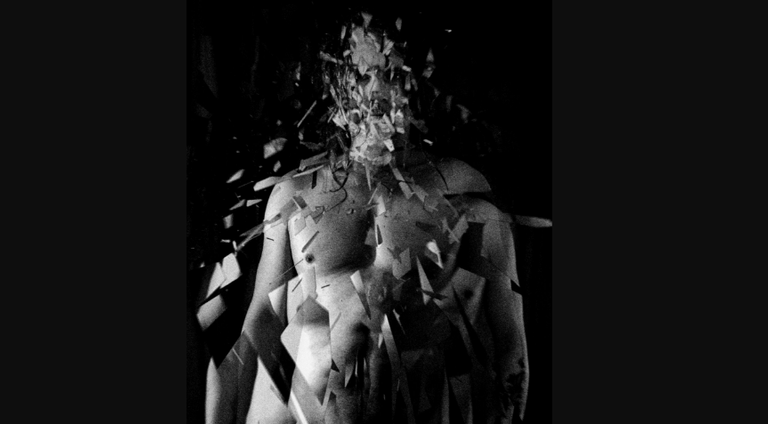

Cover Photo: Image Source

What an amazing story and novel, by the way, that I am already translating and reading that will be developing very close to a house of 200 years and living in a 100 with a Budy as a character and I hope to read all the first part and waiting for the second and thanks for choose Steemit. Blessings

I know it must be a challenge to read it in translation, so I appreciate you taking the time and the effort! Thank you for reading and for your kind comment!

Congratulations @birddroppings!

You raised your level and are now a Minnow!

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard: