A few days ago, this gem of a Steam discussion got referenced in a forum thread about Caves of Qud that I follow:

If you're literate in the vocabulary of computer game genres, you're likely facepalming pretty hard right now. And in all likelihood, especially given the user's response to the answers they received, this was a troll of the old school: stirring up rancor by posting indefensible positions around which to argue in bad faith. But it's just on the edge of plausibility, because confusion about what a genre is and how it works is quite common in gamer circles. In recent memory I also had a board gamer choose as a hill to die on the position that Gloomhaven doesn't belong in the "legacy" genre, because the core rules don't change over the course of the campaign. And just yesterday I heard about a tabletop roleplaying grognard's assertion that games inspired by Advanced Dungeons & Dragons don't belong in the OSR, despite the game that launched the OSR being a literal rebuild of the AD&D rules.

How do people get this confused?

Some deep geek psychology is at work here. Game nerds love to feel like they own the things that they love, and in a sort of libertarian-capitalist ethos, that ownership means staking out a claim and declaring a boundary across which no outsider may cross. You see this at work any time some gamerbro throws the term "fake geek girl" at a prominent cosplayer, or when a nerd lays down the True Scot law that "if you haven't mastered Dark Souls, played every Call of Duty, and ROMhacked Harvest Moon, you're not a REAL gamer". Getting to say who's in and who's out gives folks a feeling of control, power, and belonging, and when you can throw that weight around in the context of something as abstract as defining a genre, a sense of intellectual superiority as well. When something a geek doesn't like (say, a first-person game of nonviolent exploration) claims to live under the umbrella of things he does like (e.g. video games as a whole), that provokes a feeling of encroachment, and in turn a defensive reaction that looks like the above boundary-drawing ("that's not a game, it's a walking simulator").

There's also a broader cultural and intellectual backdrop that helps people think this sort of line-in-the-sand approach is logical and rational, and that's essentialism. Essentialism is the philosophical premise that all things--objects, concepts, categories--have an innate "essence" that defines what they are, and it's a noble endeavor of the mind to puzzle out and explore those inner truths. In lay discourse, we tend to see essentialism manifest in attempts to create lists of mandatory traits that a thing must have to count as an example of some other thing. To call your board game a "legacy" board game, it must involve permanent changes to physical components, AND secret information revealed over the course of play, AND these revelations must mutate the rules themselves. Etc.

Wait, isn't that what genre definitions are?

The thing is, language doesn't work like that. Definitions drift and expand over time as new examples push the boundaries. Yesterday's "Diablo clone" becomes today's "ARPG", and then a game like Borderlands comes along and bridges "ARPG" to "FPS", broadening the kinds of gameplay that might be found in both genres. Yes, in some situations it's important to push back against definitional shifts that are dangerous or harmful. Making it clear in the public consciousness that "racism against white people" does not exist in any meaningful way, for example, is a memetic battle with real consequences for politics, policy, and the safety of people of color. But in a sphere like game design, rigid genre lines have no such collective benefit.

Definitions based on mandatory traits always fail, regardless. I'm still a human being, and still Sabe, even if tomorrow my cat savages my hand and it has to be amputated. Similarly, a Roguelike that replaces its ASCII glyphs with animated graphical tiles doesn't relinquish its membership in the Roguelike club, nor does such an upgrade mean that Roguelikes still using ASCII no longer deserve the name.

And geeks, chill. No one thinks, when you say "I enjoy first-person shooters," that you mean "I enjoy EVERY first-person shooter." Your gaming palate is no less refined for liking a genre that has some examples you find dubious; you don't need to police the label.

What are some more useful ways of thinking about genre?

One possibility, posed by researchers at Northwestern University and summarized in this Extra Credits video, is to develop an understanding of genre as combinations of necessarily-subjective "aesthetics", not specific concrete "mechanics". What makes an ARPG is the sensation of crowds of monsters dying in waves under splashy screen-clearing spells, the discovery of new maps and unique items, the challenge of making a build that can subdue endgame content. And so on! Certainly this works well to stand in for the list-of-traits academic exercise, trying to distill a gamer's visceral experience of a genre into a particular cocktail of aesthetic priorities.

Another approach is to think of game lineages. This might be literal, tracking how the developers of one game (e.g. Diablo) moved on to start their own projects with similar concepts (the Torchlight series), or how creators of open-sourced games forked off from one to the next. Rogue begat Moria, which begat Angband, which begat Pernband, which begat Trouble in Middle-Earth, which became Tales of Maj'Eyal. A game lineage could also track inspiration or spiritual successorship, or even something as simple as a transitive "you might like" relationship. If you like Endless Space, you might like Stellaris, and if you like Stellaris you might like Interplanetary, on out into less and less similar games that nonetheless have some aesthetics in common from one to the next. Pick one such family tree, and you have a genre!

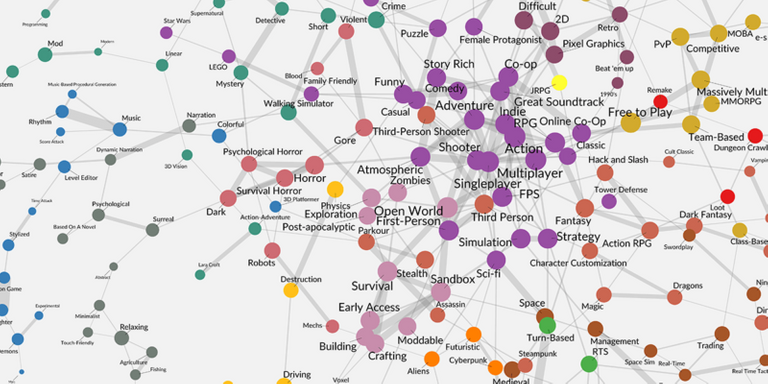

Image credit: Quantic Foundry

For everyday dialogue, though, it's probably simpler to conceive of genres as multiply overlapping big tents, or perhaps electron clouds. Nerds love Venn diagrams; by taking the Venn diagram concept but blurring the edges such that there aren't hard boundaries between "in" and "out" examples, we can think of individual games as floating closer to or further from the conceptual centers of multiple genres. Put a genre standby like Call of Duty at the center of the FPS sphere, for instance, and scatter all the Battlefields close around it, with Halo a bit further out, and then outliers like Portal in wide orbits that also fall under the aegis of puzzle and adventure games. Despite that odd visualization, I find this is the way most folks who don't stake their identities on genre rigidity talk about games. "It's a puzzle game, but using a first-person shooter perspective." "It's like a Zelda game, but with twin-stick shooter controls and Roguelike-style randomized dungeons and loot." Pick a point of reference, then communicate how far the game departs from that benchmark in the direction of other touchstones your audience is familiar with. There are no must-have elements in any genre, then, just pieces of evidence to draw upon in plotting a game's overall position among the constellations of design space.

It's all a little silly, anyway

In the end, it comes down to being a conscientious communicator and a smart consumer. Staking an absolute position, refusing to engage with the way whole communities of game-players talk about a genre, might make you feel righteous and smart, but it makes conversation harder and less productive. On the other hand, naïvely taking a genre assignment at face value is likely to lead you astray, too. A developer might slap a popular genre label on a game to improve its visibility, despite it bearing little resemblance to the genre's epicenter examples. That is, no doubt, the nightmare scenario the genre purists want to prevent. But engaging in open-minded, good faith discussion and review of games, using the aesthetic/lineage/Venn-cloud approaches posited above, is an easy antidote. If we work toward mutual understanding rather than cementing status and reinforcing identity, we'll figure out what each other's terms mean without dying on any hills at all!

When in doubt I just go with the consensus, I mean there are a lot of genres now that I just go with what most said. Since I normally review retro games I don't really get too caught on genre discussion sine normally it's pretty cut clear with games of old what type of games are.

I mean to me the binding of Issac is a top-down action adventure game, but some, but hey if the majority say it's a "roguelike" game then It is.

Thank you for addressing this, not many people go this deep.

Chic article. I learned a lot of interesting and cognitive. I'm screwed up with you, I'll be glad to reciprocal subscription))

Very beautiful philosophy

Thank you so much My Dear steemit friend

Congratulations! This post has been upvoted from the communal account, @minnowsupport, by SabreCat from the Minnow Support Project. It's a witness project run by aggroed, ausbitbank, teamsteem, theprophet0, someguy123, neoxian, followbtcnews, and netuoso. The goal is to help Steemit grow by supporting Minnows. Please find us at the Peace, Abundance, and Liberty Network (PALnet) Discord Channel. It's a completely public and open space to all members of the Steemit community who voluntarily choose to be there.

If you would like to delegate to the Minnow Support Project you can do so by clicking on the following links: 50SP, 100SP, 250SP, 500SP, 1000SP, 5000SP.

Be sure to leave at least 50SP undelegated on your account.

Congratulations @elseleth! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click here to view your Board of Honor

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDo not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Congratulations @elseleth! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board of Honor