Part 1 has already been uploaded to my Steemit page - go check it out! :)

-

SOLON BEGINS HIS TRAVELS

Once all of Solon's laws were implemented, there wasn’t a day that went by in which he didn’t receive an audience expressing their approval or disproval of a law. People were also known to approach Solon asking about the finite details of each law. Wishing to distance himself from a daily task like this, so claimed, as the owner of his own ship, he had business to attend to elsewhere, using this as his excuse to set off on regular travels. The Athenians permitted Solon 10 years to travel outside of Attica, a period of time he expected the people to have then become accustomed to his laws. While he claims it was to travel, broaden his mind and take in some views, it was more likely a means of avoiding the repercussions of implementing his new laws; The people of Athens couldn’t repeal these laws as they had sworn a solemn vow for 10 years to try out these laws.

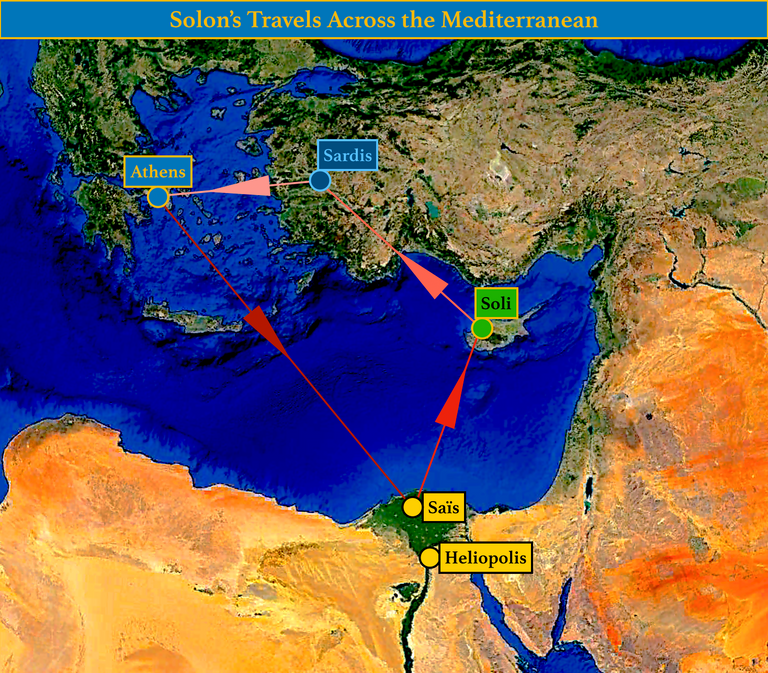

(Solon's travels across the Mediterranean, from Athens, to Egypt, to Cyprus, to Lydia, and then back to Athens)

(Solon's travels across the Mediterranean, from Athens, to Egypt, to Cyprus, to Lydia, and then back to Athens)

SOLON IN EGYPT

Solon first visited Egypt, staying “by the mouth of the Nile which adjoins the Canobic Shore”. As a member of the group around Psenopis of Heliopolis and Sonchis of Saïs, highly educated Egyptian priests, he spent time in Egypt studying philosophy. From them, Solon heard of the story of Atlantis, of which he would attempt to introduce to Greece in a poetic form.

The reign of Amasis, the then-Pharaoh, is often regarded as a high point for Egypt in terms of what the fertile land gave to the people, and in return what the people gave back to the land. There could have been anywhere around 20,000 separate inhabited cities along the Nile at this time. Amasis implemented a law stating that every citizen of Egypt should divulge in how they made a living to the governors of their provinces, decreeing that the death penalty was in order for those who did not, or for those who could not prove they made their fortune in an honest way. Solon took this law from Egypt and implemented it into his Athenian reforms.

SOLON IN CYPRUS

Solon next sailed to Cyprus. There, he became close to king Philocyprus, whose kingdom consisted of a small town, named Aepeia, perched by the River Clarius. This terrain, while easy to defend, was infertile and rugged. Solon persuaded the king to move his people down to the plains and construct a larger, more aesthetically pleasing town, and while he was visiting he took command of the town’s restlessness, and so made it a place that was not only nice to live in, but secure and safe. Resulting from this was hordes of settlers coming to Aepeia, and all other local Cypriot kings begun to look up to Philocyprus. To thus honour Solon for his aid, Philocyprus renamed the town to Soli. Solon mentions this newly-named town in his poems:

“For you, I pray that you may long dwell here as lord

Of this town of Soli, and your descendants after you;

As for me, may violet-crowned Cypris keep me unharmed

On my journey from this famous isle in my swift ship,

And, with this town here founded, may she grant me favour,

Fame, and a safe journey home to my fatherland.”

Philocyprus’s son, Aristocyprus, would go on to be routed and killed in battle by the Persian king, Darius I, during the Persian invasion of Cyprus.

SOLON IN SARDIS: MEETING CROESUS

Some claim this famous meeting to be one of fiction. However when such a story captures the character of Solon so correctly and becomes so well known, it seems perfectly OK to me to assume this meeting did actually happen, even if some minute details here-and-there aren’t accurate. Upon his arrival to the capital of the Lydian Empire at Sardis, he met with King Croesus, who put Solon as a guest in his own palace.

("Solon and Croesus" by Gerard van Honthorst, painted in 1624)

• THE STORY OF TELLUS - A couple of days following Solon’s arrival, Croesus ordered some attendants to give Solon a tour of his treasury, showing off his immense wealth. When the tour was done, Croesus found the right opportunity to ask Solon:

“My dear guest from Athens, we have often heard about you in Sardis: you are famous for your learning and your travels. We hear that you love knowledge and have journeyed far and wide, to see the world. So I really want to ask you whether you have ever come across anyone who is happier than everyone else?”

Hoping Solon would link his vast wealth with him being the happiest man alive, Solon, instead preferring truth over flattery, responded:

“Tellus of Athens.”

”What makes you think that Tellus is the happiest man?” Croesus replied.

“In the first place, while living in a prosperous state, Tellus had sons who were fine, upstanding men and he lived to see them all have children, all of whom survived. In the second place, his death came at a time when he had a good income, by our standards, and it was a glorious death. You see, in a battle at Eleusis between Athens and her neighbours he stepped into the breach and made the enemy turn tail and flee; he died, but his death was splendid, and the Athenians awarded him a public funeral on the spot where he fell, and greatly honoured him.”

• THE STORY OF CLEOBIS AND BITON - Croesus was intrigued by Solon’s prerequisites for wealth, vastly differing from his own of course, so asked who the second happiest man was.

Solon replied:

“Cleobis and Biton, because these Argives made an adequate living and were also blessed with amazing physical strength. It’s not just that the pair of them were prize-winning athletes, ; there’s also the following story about them. During a festival at Hera at Argos, their mother urgently needed to be taken to the sanctuary on her cart, but the oxen failed to turn up from the field in time. There was no time to waste, so the young men harnessed themselves to the yoke and pulled the cart with their mother riding on it. The distance to the temple was forty-five stades [over 8 km], and they took her all the way there. After this achievement of theirs, which was witnessed by the people assembled for the festival, they died in the best possible way; in fact, the god used them to show that it is better for a person to be dead than to be alive. What happened was that while the Argive men were standing around congratulating the young men on their strength, the women were telling their mother how lucky she was in her children. Their mother was overcome with joy at what her sons had done and the fame it would bring, and she went right up to the statue of the goddess, stood there and prayed that in return for the great honour her children Cleobis and Biton had done for her, the goddess would give them whatever it is best for a human being to have. After she had finished her prayer, they participated in the rites and the feast, and then the young men lay down inside the actual temple for a rest. They never got to their feet again; they met their end there. The Argives had statues made of them and dedicated them at Delphi, on the grounds that they had been the best of men.”

• SOLON EXPLAINS HOW ME MEASURES WEALTH + HAPPINESS - “My dear guest from Athens,” Croesus angrily replied, “do you hold our happiness in utter contempt? Is that why you are ranking us lower than even ordinary citizens?”

“Croesus, when you asked me about men and their affairs, you were putting your question to someone who is well aware of how utterly jealous the divine is, and how it is likely to confound us. Anyone who lives for a long time is bound to see and endure many things he would rather avoid. I place the limit of a man’s life at seventy years. Seventy years make 25,200 days, not counting the intercalary months; but if you increase the length of every other year by a month, so that the seasons happen when they should, there will be thirty-five such intercalary months in the seventy years, and these extra months will give us 1,050 days. So the sum total of all the says in seventy years is 26,250 days, but no two days bring events which are exactly the same. It follows, Croesus, that human life is entirely a matter of chance.

Now, I can see that you are extremely rich and that you rule over large numbers of people, but I won’t be in a position to say what you’re asking me to say about you until I find out that you died well. You see, someone with vast wealth is no better off than someone who lives from day to day, unless good fortune attends him and sees to it that, when he dies, he dies well and with all his advantages intact. After all, plenty of extremely wealthy people are unfortunate, while plenty of people with moderate means are lucky; and someone with great wealth but bad fortune is better off than a lucky man in only two ways, whereas there are many ways in which a lucky man is better off than someone who is rich and unlucky. An unlucky rich man is more capable of satisfying his desires and of riding out disaster when it strikes, but a lucky man is better off than him in the following respects. Even though he is not as capable of coping with disaster and his desires, his good luck protects him, and he also avoids disfigurement and disease, has no experience of catastrophe, and is blessed with fine children and good looks. If, in addition to all this, he dies a heroic death, then he is the one you are after - he is the one who deserves to be described as happy. But until he is dead, you had better refrain from calling him happy, and just call him fortunate.

Now, it is impossible for a mere mortal to have all these blessings at the same time, just as no country is entirely self-sufficient; any given country has some things, but lacks others, and the best country is the one which has the most. By the same token, no one person is self-sufficient: he has some thins, but lacks others. The person who has and retains more of these advantages than others, and then dies well, my lord, is the one who, in my opinion, deserves the description in question. It is necessary to consider then end of everything, however, and to see how it will turn out, because the god often offers prosperity to men, but then destroys them utterly and completely.”

• SOLON IS ORDERED OUT OF SARDIS - Croesus wasn’t endeared by Solon at all, immediately dismissing him from his palace. Croesus believed that a person who turned a blind eye to the present and its benefits in favour of the end of things was just plain ignorant.

(546 BC: Cyrus, king of Persia, captured Sardis, and Croesus too. Building a funeral pyre for Croesus, Cyrus made him and fourteen of Croesus’s followers climb to the top, perhaps as a victory offering. While up there, Croesus remembered the words of Solon, and how wise he had been to say that no one who is still alive is truly happy. He broke a long silence by repeating “Solon” three times aloud. Cyrus heard him, and asked his translators to interpret. After some coercion, Croesus said that Solon was “Someone whom I would give a fortune to have every ruler in the world meet”. More coercion and crowds of people around him later, Croesus told the Persians of Solon’s visit to his palace, how he dismissed his wealth as meaningless, and how everything that had happened to him since was predicted by Solon himself, and how Solon’s words to Croesus applied to anyone else. Flames flickered at Croesus’s feet as Cyrus heard of this story, changed his mind and ordered for the fire to be distinguished. When the rains did this for him instead, Cyrus declared that Croesus was in the gods’ hands, and took him in as his friend.)

SOLON'S RETURN TO ATHENS + MEETING WITH PISISTRATUS

Citizens carried on with their political feuds while Solon was away. The Plains faction was championed by Lycurgus (not related to the Spartan lawmaker), the Coast Faction was championed by Megacles, son of Alcmaeon, and the Hills were championed by Pisistratus. While the city was still being governed constitutionally, it was expected that a revolt was imminent, and that a new system of government was to soon be implemented, not because they all expected a coming state of equality but rather because they each wished to gain the advantage during the potential upheaval and thus trample over their political opponents.

This was the issue Solon had to deal with, now he was returning to Attica. And while he was respected and admired by many, he had declared himself to be too old to aid physically, or even to speak publicly. Instead, he held private meetings with party leaders, wishing they could put aside any differences and reconcile. Pisistratus seemed more interested in this idea, taken in by Solon’s supposedly charming voice and words, as Pisistratus seemed in favour of coming to the aid of the poor, and approached his political affairs calmly. But Solon was one of the few able to see him for who he really was, so wanted to calm the man down instead of hating him. Solon claimed that in order to turn him into a more ideal citizen, all that was needed was the purging from his mind of high ambitions to become tyrant.

RISE OF PISISTRATUS + SOLON'S POLITICAL END

Following Pisistratus’ self-made injury and his return after exile, he started stirring up the population, claiming his foes were conspiring against him politically. This won him lots of support, when Solon approached his side, saying:

“Pisistratus, you’re not playing the part of Homer’s Odysseus correctly. You’ve disfigured yourself just as he did, but in his case it was to trick his enemies, not to mislead his fellow citizens.”

Later, when the people were willing to take up arms for Pisistratus, they convened an assembly to allow Pisistratus his 50-strong club-armed bodyguards. Solon made a speech opposing this, similar to some lines in his poems:

“For you pay heed to the tongue and words of a subtle man.

Individually, each one of you walks with the steps of a fox,

But when you come together your thinking is vain.”

He left the assembly upon seeing for himself how much the poor wished to gratify Pisistratus, and how much the rich wished to avoid a conflict. He remarked how he had more courage than one party and more intelligence than the other. the populace thus became lenient on Pisistratus’s recruiting of bodyguards, until he had enough men to seize the Acropolis itself, plunging Athens into tyranny and chaos.

As the city plummeted into chaos, Megacles and the Alcmaeonidae quickly fled into exile, while Solon, despite his age, remained in the city centre to address the Athenians, hoping to both berate them on their timidity towards Pisistratus and to rouse them against him and fight for their freedoms. People were afraid to give him any attention, so he went home, took his armour and weapons and laid them out in the street outside his door, stating:

“I have played my part. I have done all I could to help my homeland and the laws.”

He largely kept himself to himself following this, ignoring friendly advise to go into exile instead of remaining in Athens. Instead, he wrote his poems about the Athenians:

“Your own cowardice is to blame for your wretched lives;

Bear no ill will against the gods for them.

It was you who gave these men guards and made them great,

And that is why base servitude holds you now.”

SOLON UNDER PISISTRATUS + HIS DEATH

It was these poems that caused people to warn him that they would lead to his death by the tyrant’s hand. He claimed his old age gave him his recklessness in the face of this. However, now Pisistratus was in power, he attempted to win Solon over, expressing his admiration for him and showing him kindness. He sent for him so regularly that Solon eventually became his advisor, approving of many of his ideas; many of Solon’s legislations still stood under Pisistratus, who wished to abide by them.

While serving under Pisistratus, Solon wrote up his “Magnum Opus”, which covered the legendary history of Atlantis, writing of the place like it were an abandoned plot of land. He was keen on somewhat embellishing it; He begun with endowing it with courtyards, enclosures and big porches, of a type not yet seen. Before he could complete such a task, however, he died, supposedly in about 558 BC around the age of 80, before finishing his writing.

He had served in total for 2 years under Pisistratus, and had died during the archonship of Hegestratus. There is a fable - unlikely true - that he was cremated, and his ashes were scattered on Salamis.

SOURCES

• Herodotus's "Histories"

• Plutarch, "Life of Solon"

• Oswyn Murray, "Early Greece"

• CL1GH Lectures from the University of Reading, Emma Aston

(All images used are royalty-free)

Congratulations @oo7harv!

Your post was mentioned in the Steem Hit Parade for newcomers in the following categories:

Now this... does put a smile on my face :')

I'm so glad to read that @oo7harv 😀

BTW, feel free to put one on mine by voting for me as a witness if you like my work at promoting your post and all newcomers

Congratulations @oo7harv! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPTo support your work, I also upvoted your post!

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Thats really a brave decision to create laws for 10 years and then go for traveling ^^ .. This sounds very unique to try it 😜

Oh yeah he DEFINITELY wasn't just making somewhat controversial laws and then legging it to the seas for 10 years - he just wanted to broaden his mind with a holiday I'm sure :)