Book Review: "Sam Houston and the Alamo Avengers" by Brian Kilmeade

Reading @patriamreminisci's article, I became convinced that the US had become the hegemon of the New World because birth of the Republic of Texas.

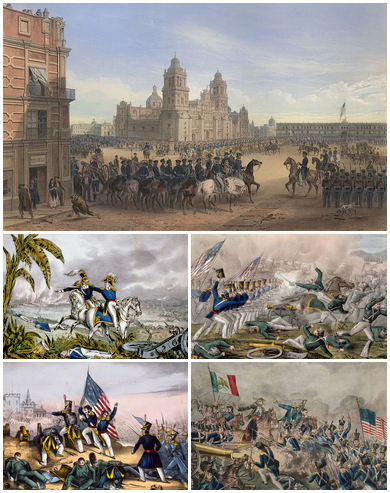

Clockwise from top left: Winfield Scott entering Plaza de la Constitución after the Fall of Mexico City, U.S. soldiers engaging the retreating Mexican force during the Battle of Resaca de la Palma, U.S. victory at Churubusco outside of Mexico City, marines storming Chapultepec castle under a large U.S. flag, Battle of Cerro GordoThe Mexican–American War,[a] also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the Intervención estadounidense en México (U.S. intervention in Mexico),[b] was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1845 U.S. annexation of Texas, which Mexico considered Mexican territory since the Mexican government did not recognize the Velasco treaty signed by Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna when he was a prisoner of the Texian Army during the 1836 Texas Revolution. The Republic of Texas was de facto an independent country, but most of its citizens wished to be annexed by the United States.[4] Domestic sectional politics in the U.S. were preventing annexation since Texas would have been a slave state, upsetting the balance of power between Northern free states and Southern slave states.[5] In the 1844 United States presidential election, Democrat James K. Polk was elected on a platform of expanding U.S. territory in Oregon and Texas. Polk advocated expansion by either peaceful means or by armed force, with the 1845 annexation of Texas furthering that goal by peaceful means.[6] However, the boundary between Texas and Mexico was disputed, with the Republic of Texas and the U.S. asserting it to be the Rio Grande River and Mexico claiming it to be the more-northern Nueces River. Both Mexico and the U.S. claimed the disputed area and sent troops. Polk sent U.S. Army troops to the area; he also sent a diplomatic mission to Mexico to try to negotiate the sale of territory. U.S. troops' presence was designed to lure Mexico into starting the conflict, putting the onus on Mexico and allowing Polk to argue to Congress that a declaration of war should be issued.[7] Mexican forces attacked U.S. forces, and the United States Congress declared war.

Beyond the disputed area of Texas, U.S. forces quickly occupied the regional capital of Santa Fe de Nuevo México along the upper Rio Grande, which had trade relations with the U.S. via the Santa Fe Trail between Missouri and New Mexico. U.S. forces also moved against the province of Alta California and then moved south. The Pacific Squadron of the U.S. Navy blockaded the Pacific coast farther south in the lower Baja California Territory. The Mexican government refused to be pressured into signing a peace treaty at this point, making the U.S. invasion of the Mexican heartland under Major General Winfield Scott and its capture of the capital Mexico City a strategy to force peace negotiations. Although Mexico was defeated on the battlefield, politically its government's negotiating a treaty remained a fraught issue, with some factions refusing to consider any recognition of its loss of territory. Although Polk formally relieved his peace envoy, Nicholas Trist, of his post as negotiator, Trist ignored the order and successfully concluded the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. It ended the war, and Mexico recognized the Mexican Cession, areas not part of disputed Texas but conquered by the U.S. Army. These were northern territories of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México. The U.S. agreed to pay $15 million for the physical damage of the war and assumed $3.25 million of debt already owed by the Mexican government to U.S. citizens. Mexico acknowledged the independence of what became the State of Texas and accepted the Rio Grande as its northern border with the United States.

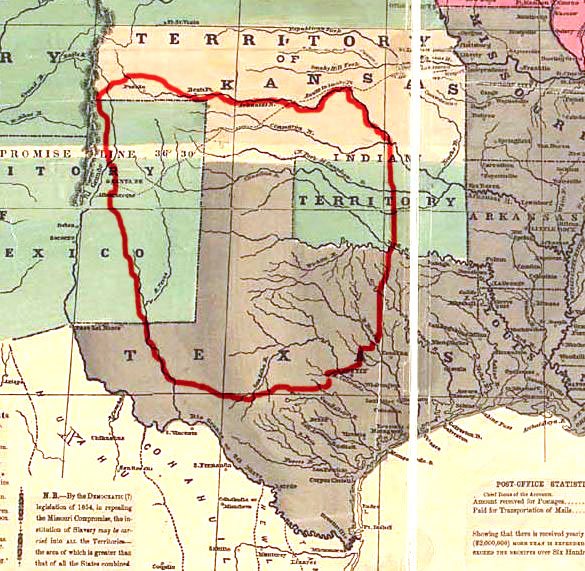

@patriamreminisci's hometown, Texas, was a very large area located between the United States and Mexico.

Texas I remember as the wealthiest region in the United States because of its abundant underground resources, including oil, and herding and agriculture.

So, Texas' existence and values were very important even within the United States now.

I was interested in the fact that Texas was originally part of Mexico. It would be interesting to imagine what the United States would be like today if Texas had been part of Mexico until now.😄

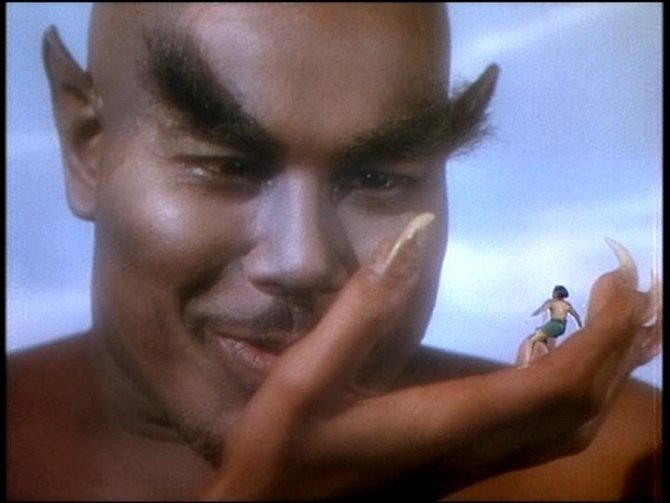

So, I decided to take a look at the history of Texas where my beloved Genie of Lamp was born.

Mexico after independence

Mexico obtained independence from the Spanish Empire with the Treaty of Córdoba in 1821 after a decade of conflict between the royal army and insurgents for independence, with no foreign intervention. The conflict ruined the silver-mining districts of Zacatecas and Guanajuato, so that Mexico began as a sovereign nation with its future financial stability from its main export destroyed. Mexico briefly experimented with monarchy, but became a republic in 1824. This government was characterized by instability,[13] leaving it ill-prepared for a major international conflict when war broke out with the U.S. in 1846. Mexico had successfully resisted Spanish attempts to reconquer its former colony in the 1820s and resisted the French in the so-called Pastry War of 1838, but the secessionists' success in Texas and the Yucatan against the centralist government of Mexico showed the weakness of the Mexican government, which changed hands multiple times. The Mexican military and the Catholic Church in Mexico, both privileged institutions with conservative political views, were stronger politically than the Mexican state.

U.S. expansionism

Main article: Manifest destiny

Since the early 19th century, the U.S. sought to expand its territory. Jefferson's Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803 gave Spain and the U.S. an undefined border. The young and weak U.S. fought the War of 1812 with Britain, with the U.S. launching an unsuccessful invasion of British Canada and Britain launching an equally unsuccessful counter-invasion. Some boundary issues were solved between the U.S. and Spain with the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1818. U.S. negotiator John Quincy Adams wanted clear possession of East Florida and establishment of U.S. claims above the 42nd parallel, while Spain sought to limit U.S. expansion into what is now the American Southwest. The U.S. then sought to purchase territory from Mexico, starting in 1825. U.S. President Andrew Jackson made a sustained effort to acquire northern Mexican territory, with no success.[14]

Historian Peter Guardino states that in the war "the greatest advantage the United States had was its prosperity."[15] Economic prosperity contributed to political stability in the U.S. Unlike Mexico's financial precariousness, the U.S. was a prosperous country with major resource endowments that Mexico lacked. Its war of independence had taken place generations earlier and was a relatively short conflict that ended with French intervention on the side of the 13 colonies. After independence, the U.S. grew rapidly and expanded westward, marginalizing and displacing Native Americans as settlers cleared land and established farms. With the Industrial Revolution across the Atlantic increasing the demand for cotton for textile factories, there was a large external market of a valuable commodity produced by slave labor in the southern states. This demand helped fuel expansion into northern Mexico. Although there were political conflicts in the U.S., they were largely contained by the framework of the constitution and did not result in revolution or rebellion by 1846, but rather by sectional political conflicts. The expansionism of the U.S. was driven in part by the need to acquire new territory for economic reasons, in particular, as cotton exhausted the soil in areas of the south, new lands had to be brought under cultivation to supply the demand for it. Northerners in the U.S. sought to develop the country's existing resources and expand the industrial sector without expanding the nation's territory. The existing balance of sectional interests would be disrupted by the expansion of slavery into new territory. The Democratic Party strongly supported expansion, so it is not by chance that the U.S. went to war with Mexico under Democratic President James K. Polk.[16]

In the 18th century, 13 North American states gained independence from British colonial rule, and the United States of America was formed.

On the other hand, the rest of the New World, including Canada and Mexico, were still colonies of European empires.

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Spanish: Virreinato de Nueva España, Spanish pronunciation: [birejˈnato ðe ˈnweβa esˈpaɲa] (audio speaker iconlisten)), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. Its jurisdiction comprised a huge area that included what are now Mexico, much of the Southwestern U.S. and California in North America, Central America, northern parts of South America, and several Pacific Ocean archipelagos, namely the Philippines and Guam.

After the 1521 Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire, conqueror Hernán Cortés named the territory New Spain, and established the new capital of Mexico City on the site of the Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Mexica (Aztec) Empire. Central Mexico became the base of expeditions of exploration and conquest, expanding the territory claimed by the Spanish Empire. With the political and economic importance of the conquest, the crown asserted direct control over the densely populated realm. The crown established New Spain as a viceroyalty in 1535, appointing as viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, an aristocrat loyal to the monarch rather than the conqueror Cortés. New Spain was the first of the viceroyalties that Spain created, the second being Peru in 1542, following the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. Both New Spain and Peru had dense indigenous populations at conquest as a source of labor and material wealth in the form of vast silver deposits, discovered and exploited beginning in the mid 1500s.

New Spain developed highly regional divisions based on local climate, topography, distance from the capital and the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz, size and complexity of indigenous populations, and the presence or absence of mineral resources. Central and southern Mexico had dense indigenous populations, each with complex social, political, and economic organization, but no large-scale deposits of silver to draw Spanish settlers. By contrast, the northern area of Mexico was arid and mountainous, a region of nomadic and semi-nomadic indigenous populations, which do not easily support human settlement. In the 1540s, the discovery of silver in Zacatecas attracted Spanish mining entrepreneurs and workers, to exploit the mines, as well as crown officials to ensure the crown received its share of revenue. Silver mining became integral not only to the development of New Spain, but to the Spanish crown, which depended on the revenues from silver mining, vastly enriching Spain and transformed the global economy. New Spain's port of Acapulco became the New World terminus of the transpacific trade with the Philippines via the Manila galleon. The New Spain became a vital link between Spain's New World empire and its East Indies empire.

From the beginning of the 19th century, the kingdom fell into crisis, aggravated by the 1808 Napoleonic invasion of Iberia and the forced abdication of the Bourbon monarch, Charles IV. This resulted in the political crisis in New Spain and much of the Spanish Empire. in 1808, which ended with the government of Viceroy José de Iturrigaray. Later, it gave rise to the Conspiracy of Valladolid and the Conspiracy of Querétaro. This last one was the direct antecedent of the Mexican War of Independence. At its conclusion in 1821, the viceroyalty was dissolved and the Mexican Empire was established. Former royalist military officer turned insurgent for independence Agustín de Iturbide would be crowned as emperor.

When the United States gained independence, Mexico was called the Spanish colony, New Spain.

At that time, the territory of Mexico, called New Spain, was twice as large as it is today.

Wow, I have now discovered the surprising fact that the areas in which the king of the Rocky Mountains, and the my Genie of the Lamp live, were all Mexican territory in the past.😦

However, the area inhabited by the King of Oregon and the handsome Monkey King was formerly British territory.😀

The vastness of North America always overwhelms me.😲

That vast territory governed by the United States will be twice the size of mainland China.😳

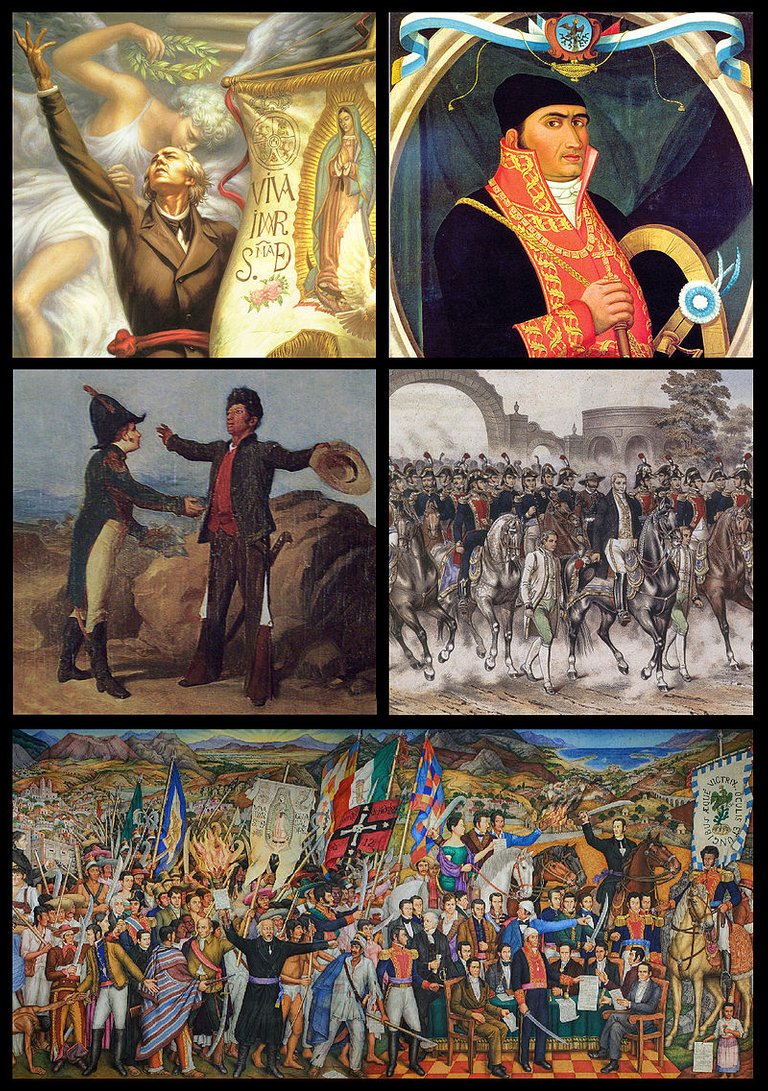

The Mexican War of Independence (Spanish: Guerra de Independencia de México, 16 September 1810 – 27 September 1821) was an armed conflict and political process resulting in Mexico's independence from Spain. It was not a single, coherent event, but local and regional struggles that occurred within the same time period, and can be considered a revolutionary civil war.[2] Independence was not an inevitable outcome, but events in Spain itself had a direct impact on the outbreak of the armed insurgency in 1810 and its course until 1821. Napoleon Bonaparte's invasion of Spain in 1808 touched off a crisis of legitimacy of crown rule, since he had placed his brother Joseph on the Spanish throne after forcing the abdication of the Spanish monarch Charles IV. In Spain and many of its overseas possessions, the local response was to set up juntas ruling in the name of the Bourbon monarchy. Delegates in Spain and overseas territories met in Cádiz, Spain, still under Spanish control, as the Cortes of Cádiz, which drafted the Spanish Constitution of 1812. That constitution sought to create a new governing framework in the absence of the legitimate Spanish monarch. It tried to accommodate the aspirations of American-born Spaniards, for more local control and equal standing with Peninsular-born Spaniards, known locally as Peninsulares. This political process had far reaching impacts in New Spain, during the independence period and beyond. Pre-existing cultural, religious and racial divides in Mexico played a major role in not only the development of the independence movement but also the development of the conflict as it progressed.[3][4]

In September 1808 peninsular-born Spaniards in New Spain overthrew the rule of Viceroy José de Iturrigaray (1803–08), who had been appointed before the French invasion. In 1810, American-born Spaniards in favor of independence began plotting an uprising against Spanish rule. It occurred when the parish priest of the village of Dolores, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, issued the Cry of Dolores on September 16, 1810. The Hidalgo revolt began the armed insurgency for independence, lasting until 1821. The colonial regime did not expect the size and duration of the insurgency, which spread from the Bajío region north of Mexico City to the Pacific and Gulf Coasts. With Napoleon's defeat, Ferdinand VII succeeded to the throne of the Spanish Empire in 1814, and promptly repudiated the constitution and returned to absolutist rule. When Spanish liberals overthrew the autocratic rule of Ferdinand VII in 1820, conservatives in New Spain saw political independence as a way to maintain their position. Former royalists and old insurgents formed an alliance under the Plan of Iguala and forged the Army of the Three Guarantees. The momentum of independence saw the collapse of royal government in Mexico and the Treaty of Córdoba ended the conflict.[5]

The mainland of New Spain was organized as the Mexican Empire.[6] This ephemeral Catholic monarchy was overthrown and a federal republic declared in 1823 and codified in the Constitution of 1824. After some Spanish reconquest attempts, including the expedition of Isidro Barradas in 1829, Spain under the rule of Isabella II recognized the independence of Mexico in 1836.[7]

In the early 19th century, when Napoleon destroyed the Bourbon dynasty in Spain, the Mexicans began a war of independence from the Spanish Empire.

After a long war, Mexico gained independence from the Spanish Empire.

This new country, the second country to be born in the New World after the United States, changed its name from New Spain, a colony of the Spanish Empire, to Mexico.

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (Spanish pronunciation: [anˈtonjo ˈlopez ðe ˌsan'taːna]; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),[1] usually known as Santa Anna[2] or López de Santa Anna, was a Mexican politician and general. His influence on post-independence Mexican politics and government in the first half of the nineteenth century is such that historians of Mexico often refer to it as the "Age of Santa Anna".

Santa Anna agreed with important points in the Monroe Doctrine whereby European powers would not use Dons, Lords, and Governors as absentee landlords of their conquered lands in the Americas. He disagreed with the U.S on slavery; but he did not agree to allow Africans into his territory as freed slaves. He carried out vicious attacks against Native Mexican American tribes.[3] He was called[by whom?] "the Man of Destiny" who "loomed over his time like a melodramatic colossus, the uncrowned monarch".[4]

Santa Anna's military and political career featured a series of reversals. He at first opposed Mexican independence from Spain, but then fought in support of it. He backed the monarchy of First Mexican Empire, then revolted against the emperor. He "represents the stereotypical caudillo in Mexican history".[5][need quotation to verify][6][need quotation to verify] Lucas Alamán writes that "the history of Mexico since 1822 might accurately be called the history of Santa Anna's revolutions. His name plays a major role in all the political events of the country and its destiny has become intertwined with his."[7]

Santa Anna, an enigmatic, patriotic, and controversial figure, wielded great power and influence in Mexico during the turbulent 40 years of his political career. He led as general at crucial points and served 11 non-consecutive presidential terms over a period of 22 years.[a] In the periods when he was not serving as president, he continued to pursue his military career.[9] He was a wealthy landowner who built a political base in the port city of Veracruz.

Perceived as a hero by his troops, Santa Anna sought glory for himself and for his army and independence for Mexico. He repeatedly rebuilt his reputation after major losses. Yet historians and many[quantify] Mexicans rank him as one of "those who failed the nation".[10] His centralist rhetoric and military failures resulted in Mexico losing half its territory, beginning with the Texas Revolution of 1836 and continuing with the Mexican Cession of 1848 following Mexico's loss to the United States in the Mexican–American War of 1846–1848. Santa Anna was also a general in the Pastry War, which cost him his left leg. His leadership in the Mexican-American War and his willingness to fight to the bitter end prolonged the war: "[...] more than any other single person it was Santa Anna who denied Polk's dream of a short war."[11] After the debacle of the war, he returned to the Mexican presidency and in 1853 sold Mexican territory to the U.S. Overthrown by the liberal Revolution of Ayutla in 1855, he lived most of his later years in exile.

Mexico was the second country in the New World to gain independence from European colonies after the United States.

Mexico may have surpassed the United States in national power because it possessed more territory than the United States outwardly.

However, Mexico was constantly plagued by internal divisions, civil wars and revolutions.

Mexico's ambitious generals used the power of their military to revolutionize and seize power.

The Catholic Churches also waged wars for wealth and power.

So, Mexico was divided and civil wars continued.

Santa Anna, known as the George Washington of Mexico, was ambitious, adventurous and immoral. He became president of Mexico several times because he was more capable than his other rivals, and because of his luck.

Mexico fell into misery when an immoral figure like Santa Anna became its builder. I guess that if he had the personality and ideals of George Washington, the fate of Mexico would have changed.

I remember @roleerob saying George Washington was the American he admired the most.😄

I didn't understand @roleerob's argument at the time, but watching Santa Anna, I could understand @roleerob's argument.😯

God sent George Washington to America, but Santa Anna to Mexico.

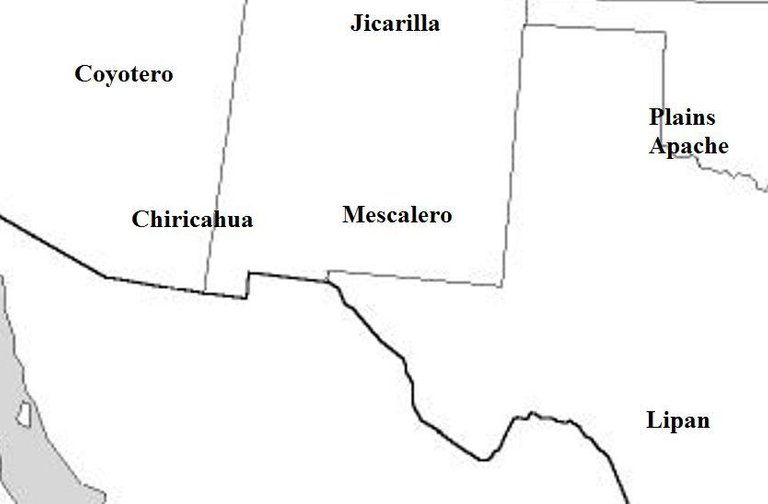

The approximate boundaries of Comancheria.The Comanche–Mexico Wars was the Mexican theater of the Comanche Wars, a series of conflicts from 1821 to 1870. There were large-scale raids into northern Mexico by the Comanche and their Kiowa and Kiowa Apache allies, which left thousands of people dead.[1] The Comanche raids were sparked by the declining military capability of Mexico during the turbulent years after it gained independence in 1821, as well as a large and growing market in the United States for stolen Mexican horses and cattle.[2]

The approximate locations of the principal Apache tribes, ca. 1840. Most of the raids into Mexico were carried out by the Chiricahua and Mescalero.When the US Army invaded northern Mexico in 1846 during the Mexican–American War, the region was devastated. The largest Comanche raids into Mexico took place from 1840 to the mid-1850s, when they declined in size and intensity. The Comanche were finally defeated by the US in 1875 and forced onto a reservation.

The Apache–Mexico Wars, or the Mexican Apache Wars, refer to the conflicts between Spanish or Mexican forces and the Apache peoples. The wars began in the 1600s with the arrival of Spanish colonists in present-day New Mexico. War between the Mexicans and the Apache was especially intense from 1831 into the 1850s. Thereafter, Mexican operations against the Apache coincided with the Apache Wars of the United States, such as during the Victorio Campaign. Mexico continued to operate against hostile Apache bands as late as 1915.[1][2]

While Santa Anna eliminated rivals and seized power in Mexico, northern Mexico and Texas were plagued by invasion and looting by the Comanche and Apache confederations.

The Comanche and Apache League, which was formed by the alliance of several Indian tribes, was so numerous and powerful that Mexico and Texas suffered from their invasions.

The Comanche and Apache were so powerful that Mexicans and Texans who had suffered from the Comanche and Apache invasions and looting paid tribute to the Comanche and Apache.

So, the Texans initially asked for Mexico's protection, but after seeing Mexico's incompetence, they eventually tried to gain independence from Mexico.

However, Mexico did not allow Texas to become independent and war eventually broke out.

Texas' war of independence against Mexico was also due to the fact that the number of American immigrants in Texas surpassed that of Mexicans.

American immigrants living in Texas had a difficult time coexisting with Mexicans linguistically and culturally.

American immigrants in Texas founded the Republic of Texas because they were outraged that the Mexican government had left them in the invaisons of the Comanche and Apache

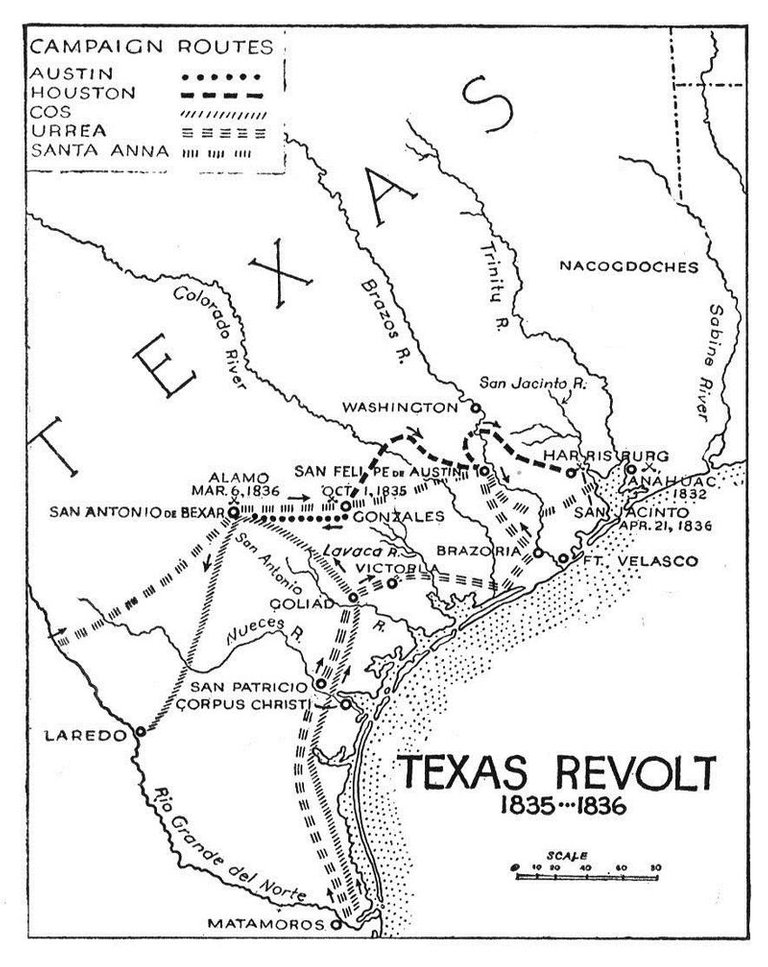

The campaigns of the Texas RevolutionThe Texas Revolution (October 2, 1835 – April 21, 1836) was a rebellion of colonists from the United States and Tejanos (Hispanic Texans) in putting up armed resistance to the centralist government of Mexico. While the uprising was part of a larger one, the Mexican Federalist War, that included other provinces opposed to the regime of President Antonio López de Santa Anna, the Mexican government believed the United States had instigated the Texas insurrection with the goal of annexation. The Mexican Congress passed the Tornel Decree, declaring that any foreigners fighting against Mexican troops "will be deemed pirates and dealt with as such, being citizens of no nation presently at war with the Republic and fighting under no recognized flag". Only the province of Texas succeeded in breaking with Mexico, establishing the Republic of Texas, and eventually being annexed by the United States.

The revolution began in October 1835, after a decade of political and cultural clashes between the Mexican government and the increasingly large population of American settlers in Texas. The Mexican government had become increasingly centralized and the rights of its citizens had become increasingly curtailed, particularly regarding immigration from the United States. Mexico had officially abolished slavery in Texas in 1830, and the desire of Anglo Texans to maintain the institution of chattel slavery in Texas was also a major cause of secession.[1][2][3][4][5] Colonists and Tejanos disagreed on whether the ultimate goal was independence or a return to the Mexican Constitution of 1824. While delegates at the Consultation (provisional government) debated the war's motives, Texians and a flood of volunteers from the United States defeated the small garrisons of Mexican soldiers by mid-December 1835. The Consultation declined to declare independence and installed an interim government, whose infighting led to political paralysis and a dearth of effective governance in Texas. An ill-conceived proposal to invade Matamoros siphoned much-needed volunteers and provisions from the fledgling Texian Army. In March 1836, a second political convention declared independence and appointed leadership for the new Republic of Texas.

Determined to avenge Mexico's honor, Santa Anna vowed to personally retake Texas. His Army of Operations entered Texas in mid-February 1836 and found the Texians completely unprepared. Mexican General José de Urrea led a contingent of troops on the Goliad Campaign up the Texas coast, defeating all Texian troops in his path and executing most of those who surrendered. Santa Anna led a larger force to San Antonio de Béxar (or Béxar), where his troops defeated the Texian garrison in the Battle of the Alamo, killing almost all of the defenders.

A newly created Texian army under the command of Sam Houston was constantly on the move, while terrified civilians fled with the army, in a melee known as the Runaway Scrape. On March 31, Houston paused his men at Groce's Landing on the Brazos River, and for the next two weeks, the Texians received rigorous military training. Becoming complacent and underestimating the strength of his foes, Santa Anna further subdivided his troops. On April 21, Houston's army staged a surprise assault on Santa Anna and his vanguard force at the Battle of San Jacinto. The Mexican troops were quickly routed, and vengeful Texians executed many who tried to surrender. Santa Anna was taken hostage; in exchange for his life, he ordered the Mexican army to retreat south of the Rio Grande. Mexico refused to recognize the Republic of Texas, and intermittent conflicts between the two countries continued into the 1840s. The annexation of Texas as the 28th state of the United States, in 1845, led directly to the Mexican–American War.

Santa Anna marched to Texas to suppress the Republic of Texas' independence from Mexican rule.

The Alamo, as drawn in 1854The Battle of the Alamo (February 23 – March 6, 1836) was a pivotal event in the Texas Revolution. Following a 13-day siege, Mexican troops under President General Antonio López de Santa Anna reclaimed the Alamo Mission near San Antonio de Béxar (modern-day San Antonio, Texas, United States), killing most of the Texians and Tejanos inside. Santa Anna's cruelty during the battle inspired many Texians and Tejanos to join the Texian Army. Buoyed by a desire for revenge, the Texians defeated the Mexican Army at the Battle of San Jacinto, on April 21, 1836, ending the rebellion in favor of the newly-formed Republic of Texas.

Several months previously, Texians had driven all Mexican troops out of Mexican Texas. About 100 Texians were then garrisoned at the Alamo. The Texian force grew slightly with the arrival of reinforcements led by eventual Alamo co-commanders James Bowie and William B. Travis. On February 23, approximately 1,500 Mexicans marched into San Antonio de Béxar as the first step in a campaign to retake Texas. For the next 10 days, the two armies engaged in several skirmishes with minimal casualties. Aware that his garrison could not withstand an attack by such a large force, Travis wrote multiple letters pleading for more men and supplies from Texas and from the United States, but the Texians were reinforced by fewer than 100 men because the United States had a treaty with Mexico, and supplying men and weapons would have been an overt act of war.

In the early morning hours of March 6, the Mexican Army advanced on the Alamo. After repelling two attacks, the Texians were unable to fend off a third attack. As Mexican soldiers scaled the walls, most of the Texian fighters withdrew into interior buildings. Occupiers unable to reach these points were slain by the Mexican cavalry as they attempted to escape. Between five and seven Texians may have surrendered; if so, they were quickly executed. Several noncombatants were sent to Gonzales to spread word of the Texian defeat. The news sparked both a strong rush to join the Texian army and a panic, known as "The Runaway Scrape", in which the Texian army, most settlers, and the new, self-proclaimed but officially unrecognized, Republic of Texas government fled eastward toward the United States ahead of the advancing Mexican Army.

Within Mexico, the battle has often been overshadowed by events from the Mexican–American War of 1846–48. In 19th-century Texas, the Alamo complex gradually became known as a battle site rather than a former mission. The Texas Legislature purchased the land and buildings in the early part of the 20th century and designated the Alamo chapel as an official Texas State Shrine. The Alamo has been the subject of numerous non-fiction works beginning in 1843. Most Americans, however, are more familiar with the myths and legends spread by many of the movie and television adaptations,[5] including the 1950s Disney mini-series Davy Crockett and John Wayne's 1960 film The Alamo.

Santa Anna won the Battle of the Alamo.

I remember seeing the 1960 movie The Alamo, starring John Wayne. However, the movie wasn't very interesting. I remembered that the actress was beautiful.😄

The film symbolized typical American heroism.

Did my friend @joeyarnoldvn watched that movie?

The Battle of San Jacinto (Spanish: Batalla de San Jacinto), fought on April 21, 1836, in present-day La Porte and Pasadena, Texas, was the final and decisive battle of the Texas Revolution. Led by General Samuel Houston, the Texan Army engaged and defeated General Antonio López de Santa Anna's Mexican army in a fight that lasted just 18 minutes. A detailed, first-hand account of the battle was written by General Houston from the headquarters of the Texan Army in San Jacinto on April 25, 1836.[3] Numerous secondary analyses and interpretations have followed.

General Santa Anna, the president of Mexico, and General Martín Perfecto de Cos both escaped during the battle. Santa Anna was captured the next day on April 22 and Cos on April 24. After being held for about three weeks as a prisoner of war, Santa Anna signed the peace treaty that dictated that the Mexican army leave the region, paving the way for the Republic of Texas to become an independent country. These treaties did not necessarily recognize Texas as a sovereign nation but stipulated that Santa Anna was to lobby for such recognition in Mexico City. Sam Houston became a national celebrity, and the Texans' rallying cries from events of the war, "Remember the Alamo" and "Remember Goliad" became etched into Texan history and legend.

However, Santa Anna was defeated by Sam Huston in The Battle of San Jacinto (Spanish: Batalla de San Jacinto), which resulted in the Republic of Texas gaining independence from Mexican rule.

Boundaries of Texas after the annexation in 1845The Texas annexation was the 1845 annexation of the Republic of Texas into the United States of America. Texas was admitted to the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Republic of Texas declared independence from the Republic of Mexico on March 2, 1836. It applied for annexation to the United States the same year, but was rejected by the Secretary of State. At the time, the vast majority of the Texian population favored the annexation of the Republic by the United States. The leadership of both major U.S. political parties, the Democrats and the Whigs, opposed the introduction of Texas, a vast slave-holding region, into the volatile political climate of the pro- and anti-slavery sectional controversies in Congress. Moreover, they wished to avoid a war with Mexico, whose government refused to acknowledge the sovereignty of its rebellious northern province. With Texas's economic fortunes declining by the early 1840s, the President of the Texas Republic, Sam Houston, arranged talks with Mexico to explore the possibility of securing official recognition of independence, with the United Kingdom mediating.

In 1843, U.S. President John Tyler, then unaligned with any political party, decided independently to pursue the annexation of Texas in a bid to gain a base of support for another four years in office. His official motivation was to outmaneuver suspected diplomatic efforts by the British government for emancipation of slaves in Texas, which would undermine slavery in the United States. Through secret negotiations with the Houston administration, Tyler secured a treaty of annexation in April 1844. When the documents were submitted to the U.S. Senate for ratification, the details of the terms of annexation became public and the question of acquiring Texas took center stage in the presidential election of 1844. Pro-Texas-annexation southern Democratic delegates denied their anti-annexation leader Martin Van Buren the nomination at their party's convention in May 1844. In alliance with pro-expansion northern Democratic colleagues, they secured the nomination of James K. Polk, who ran on a pro-Texas Manifest Destiny platform.

In June 1844, the Senate, with its Whig majority, soundly rejected the Tyler–Texas treaty. The pro-annexation Democrat Polk narrowly defeated anti-annexation Whig Henry Clay in the 1844 presidential election. In December 1844, lame-duck President Tyler called on Congress to pass his treaty by simple majorities in each house. The Democratic-dominated House of Representatives complied with his request by passing an amended bill expanding on the pro-slavery provisions of the Tyler treaty. The Senate narrowly passed a compromise version of the House bill (by the vote of the minority Democrats and several southern Whigs), designed to provide President-elect Polk the options of immediate annexation of Texas or new talks to revise the annexation terms of the House-amended bill.

On March 1, 1845, President Tyler signed the annexation bill, and on March 3 (his last full day in office), he forwarded the House version to Texas, offering immediate annexation (which preempted Polk). When Polk took office at noon EST the next day, he encouraged Texas to accept the Tyler offer. Texas ratified the agreement with popular approval from Texans. The bill was signed by President Polk on December 29, 1845, accepting Texas as the 28th state of the Union. Texas formally joined the union on February 19, 1846. Following the annexation, relations between the United States and Mexico deteriorated because of an unresolved dispute over the border between Texas and Mexico, and the Mexican–American War broke out only a few months later.

However, Mexico later refused to recognize the independence of the Republic of Texas, and the two countries continued to clash. The conflict between the two countries eventually led to war between the United States and Mexico, and the United States eventually annexed Texas.

I observed with interest the historical event that the Republic of Texas, which was born as a result of the Texas Revolution, became the cause of the war between the United States and Mexico.

The United States at first appeared to have no ability or desire to have Texas.

However, the long-standing conflict between Mexico and Texas cost the US political, economic, and geopolitical interests, and eventually the US went to war with Mexico.

The war between the United States and Mexico ended in the form of the US government paying off Mexico's debts to the Americans and paying Mexico $15 million to purchase Mexican territories.😦

From my point of view, the $15 million the United States paid Mexico for land felt too cheap.

In particular, considering the importance and value of the present Texas, I felt that way!😯

One thing is certain: after the US took Texas, the US took over the hegemony of the New World!

Your views are always insightful, and you put things in a new perspective most of us "New Worlders" do not often see.

I would say the Texas Revolution was one of two major turning points which shifted North America's balance of power from Mexico toward the US. The other was the US acquisition of California.

Speaking of that, that reminds me of the Californian Gold Rush of the 1800s and also the Oregon Trail which was also in the 1800s which there is a television show on Hulu or Netflix or something, it's called 1883 and it is pretty good.

Dear @patriamreminisci, I wonder an America's history!😄

Thank you!

Mexico has a messy past. Well, even to this day, there are cartels in Mexico for example. I like Texas. I don't like the New World Order. I do like America. I do like the New World, AKA America. According to maps I've look at, it looks like America, China, Russia, and Australia are roughly the same size. I forget exactly how large these countries are but I believe they are probably the largest 4 countries nowadays. The history of America can be complex in regards to all of the different countries who would try to conquer parts of America.

Dear @joeyarnoldvn , What is AKA America? There are many cartels in Mexico!

The United States is the country that dominates the entire New World. At least North America belongs to the de facto sovereignty of the United States.

The area of North America under US control is twice that of mainland China.

When I say "AKA" I mean in other words or "Also known as." I kind of forgot AKA is like slang or code or an idiom or an abbreviation or something. Oh, let me Google it. Ok, I got it. AKA is an abbreviation of ALSO KNOWN AS. AKA or aka or a.k.a. is used especially when referring to someone's nickname or stage name. I found it hard to find the right definition on the Internet. That is coming from me, a King of Finding Things on the Web. Sometimes, I find it hard to find things via Google or other search engines. I think that is crazy that it can be so hard for me to find things even when I know what I am looking for. I know how to find things. I knew what AKA meant for example but I wanted to find an article online that talked about AKA. I only found a few websites with the correct definition. It can be hard because aka could mean other things too. But when I say AKA, this is the meaning I have. Most people use this definition in America when they say AKA. People generally pronounce AKA as three letters or syllables. So you say Aye-Kay-Aye. As in the three letters of AKA. I have been looking for things on the Internet for over 24 years or so. I am good at it. I am always learning how to use Google, Bing, Yahoo, Duck, other search engines. It is a skill to find things. I cannot imagine how hard it can be for other people to find things via Google, etc. Because it is even hard for me and I am expert Googler. I am Google Master. Not just a Monkey Master. But an Internet Master. If Internet Search is hard for me, then it might be even harder for you and other people.

America had a lot of power in the 1900s, the 20th century. But China is trying to take over the world in the 21st century. Why do you say America is bigger than China? Who told you that or is it based on a map you saw? Perhaps you saw the wrong map. Some maps have Africa as smaller than it really. I believe some maps will make Asia look smaller than it really is in order to make North America look bigger. So, therefore, it depends on the map you saw. Do you mean America has military bases all around the world? Because that is true. But Canada is not America. When you say America, do you mean United States? Because Canada is not the USA. But Canada and USA together is probably bigger than China and maybe bigger than Russia. Well, Canada has many large rivers, lakes, seas, and including them would make Canada very big. Europe and Asia together would probably be bigger than Africa. But Asia alone is still a pretty big continent and Asia might be bigger than Africa. I think Africa and Asia are the largest two continents out of the total seven continents on earth. I think Africa is the biggest continent but I am not sure. Some people think there are more than 7 continents assuming earth is flat. But the earth is probably not flat. Maybe earth is hollow but probably not flat. So, I think there are only 7 continents.

Dear @joeyarnoldvn, If you look at the current map of mainland China, you will agree with me. China forcibly annexed Tibet and Uyghurs to make it part of what is now China. If you look at the current map of mainland China, Tibet and Uyghurs are Chinese territories.

I believe that American rule is controlling the whole of the New World.

At least the direct U.S. powers govern all of North America.

I think the real power of the US governs all of North America. So, I said that the continent of North America, dominated by the power of American rule, is larger than that of China.

Congratulations @goldgrifin007! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s):

Your next target is to reach 900 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out the last post from @hivebuzz: