A while back, I waxed extensive on the Ethiopia Bensa Bombe from Onyx Coffee Roasters in Fayetteville, AR. I said then that I hadn’t given up on the coffees from Onyx, as they’re a nationally-noted coffee roaster, they’re only a couple of hours from where I live, and they provide a ton of training options for regular people from some world-class baristas.

All this is worth something in my book, and just because I was a bit disappointed in what turned out, at least to me, to be an overpriced bag of craft coffee, I wasn’t willing to toss in the towel on their coffees. They have methods and practices that I really agree with on a philosophical level, and that’s also super important. It’s not just the coffee itself, it’s everything else that goes into creating that coffee. That’s the thing about coffee—it’s not one size fits all—and I like that. Not everyone is going to like everything—everyone’s priorities on coffee are different—and that’s okay.

Something else that Onyx does is to include a scale of how “traditional” or “modern” the coffee is in the cup. This hearkens to not only the body of the coffee but also the taste as well as the roast. Modern coffees have many more fruity elements, and many times are not as dark or full-bodied when compared to your traditional/standard coffees. Modern coffees, especially coffees created in accordance with Third Wave methods, really pay true homage to the characteristics of the green coffee. They’re not roasted as dark as traditional coffees, therefore you’ll taste more of the actual coffee cherry and even the soil in which the coffee is grown in the cup—rather than just tasting the darkness of the roast.

I was brought up in the world of Second Wave coffee, and we were generally snobs who believed that if it wasn’t roasted almost into oblivion that it wasn’t worth drinking—In reality, that coffee was generally roasted so dark that we were hardly tasting the coffee itself and tasting the roast more than anything—my mind has been so expanded in the past few months that I’ve been diving deeply into Third Wave coffee. Coffee is bigger than any of us in Second Wave gave it credit for. I sometimes think about all of the dark and French-roasted coffee I’ve had over the years and wonder what I was really missing out on while I was drinking liquid ash (coffee roasted so dark that you’re not even really experiencing the beans).

There’s so much to be said for green coffee (coffee beans that have not yet been roasted) and everything that goes into its growth and processing even before it gets to the domestic roaster. The reason I mention elevation is because it makes a difference. The higher the elevation the coffee is grown at, the more the coffee “struggles” to develop the flavor, and the more complex and sweeter the flavor profile of the green coffee will be. (If any of you are aficionados for marijuana or for hops in beer, the themes are similar in this regard.)

With coffee, the processing method also makes a massive difference in its ultimate flavor profile. To fully understand this is also to understand what green coffee actually is. See, the coffee “bean” is really essentially a pit in a coffee cherry. They’re beautiful berries with a pit, and the skin and mucilage/fruit needs to be removed from around the pit before the coffee can be made. This is quite a process—especially in countries that do not live in super-automated worlds where everything is done by high-technology machines.

Third Wave craft coffees from small roasters, is planted, tended, harvested, dried and processed by hand in their native environments all over the world. There are a lot of natural resources and hard work that goes into making each crop, and all of these methods employed by various farmers and mills make a difference in how the coffee ultimately cups. Not all coffee is created equally.

This also helps to explain the price tag on some of these more expensive craft coffees. If you feel like you’re paying too much for that cup, just remember that the money you spend on that retail bag helps to keep these small farmers and families employed. Your purchase with a higher price tag makes the market more fair for these people who spend the time and resources to bring that quality coffee into your cup.

Coffee has been underpriced for years, and primarily the Western market has taken massive advantage of the farmers who work tirelessly to create a quality product. These farmers are growing a fruit for the exclusive use of the pit of that fruit—and there’s a lot of waste involved in this process. It’s an expensive game, and the farm-level support helps the farmers to not only continue to make a good cup, but also it ensures these real families have food to put on their tables, places to live, and clothes to wear.

I urge you to take a look at the import methods and pricing used for the coffee you drink. At the very least, please make a point to purchase coffee with Fair Trade certification—this helps level the playing field and helps reduce the amount of importers taking advantage of these farmers. We owe it to them for bringing us quality coffee—and they deserve compensation.

If the roaster doesn’t mention it—or even brag on it—they probably don’t do this. Pay attention...and please try to support roasters who support farmers.

(As a quick aside, one of the things I love about Onyx is that they are very transparent about their purchase prices and farm-to-cup processes, and very regularly purchase coffee far above the commodity and even the Fair Trade prices. They call this “relationship coffee,” and I really like the concept.)

Let’s Talk A Bit About Processing

Coffee is processed in three main types: dry/natural,, wet/washed,, and honey/fully washed. Wet-hulled processing is another type, but is mainly used to process coffees only from Sumatra, and I’ll cover this processing in a future review.

This is essentially just a processing primer and introduction to these different methods, and I’ll be covering each in a more in-depth manner in the future.

All coffee processing involves a time of fermentation after it is harvested. The methods of this fermentation are what create the different varieties of processing. Each gives the coffee a different characteristic—whether it be showing the flavor of the pit or bean itself, or imparting flavor from the fruit around the bean, or a combo of both of those—these methods of fermentation make a huge difference in the finished product.

Natural-processed coffee is native to Ethiopia, and is probably the most basic and traditional way to process the fruit. It’s also the oldest. The cherries are washed and the whole fruit, with both the pulp and mucilage in tact, are laid out in the sun to dry naturally on raised beds or concrete patios for sometimes up to 30 days. Hence, the “natural” process. The fruit in the cherries ferments during this time, and then the pits are removed. This method, while uses the least amount of technology and natural resources in the processing, also depends highly on the climate and elevation being “just right.” When the coffees ferment in the sun—it requires a fairly specific ecosystem for this to happen effectively. Too much moisture in the air, and the coffee ferments too much and doesn’t dry—and conversely, if it’s too dry, then the coffee will dry out before the fermentation can cure adequately. These dry-processed are sometimes called “sun dried” coffees and are known for being flavorful with notes of wine (due to the longer fermentation) and contribute to the classic flavor profiles that Ethiopian coffees are known for.

Wet-process or washed coffee is mostly used in circles of the highest quality coffees. It causes single origin coffees to really shine, as it draws out the true characteristics of the green coffee itself. This process, while it creates a great cup, also takes a lot of natural resources to process in this manner, which can also translate to a higher price tag once the coffees are roasted domestically and brought to the retail market. In this processing method, the coffee cherries are run through a machine that removes the outer skin, and then the cherries (with their fruit/mucilage still in tact) are soaked in fermentation tanks filled with water for one or two days. Then the fruit is washed away from the coffee, using more water yet again. Coffee produced in this manner uses a great quantity of resources, but it also gives the coffee a more consistent outcome that isn’t dependent as much on climate after harvest. It also gives the cup more characteristics of the bean itself, rather than of the fruit around the bean. It’s also noted that coffees produced in this manner give more of a profile of the “terroir” or the literal soil and land characteristics in which the coffee is grown.

Honey-process is a favorite of mine, and a very creative way to process coffee. It adds a sweetness to the overall flavor in the cup, as the process involves letting the coffee dry and ferment with either all or part of the mucilage in tact to the bean. It’s really a mid-way process between wet and washed. This method has the name “honey” to describe the process, as the mucilage becomes sticky and sweet around the outside, coloring the flavor of the beans as it ferments. Coffees processed in this manner have a fruitier taste—berries and brightness shine in the cup from this method. While washed coffees are also known for their fruity tastes, I think honey processed coffees really bring forth the fruited notes, as they are processed without the influence of the bitterness of the outer skin, and allowing the fruit itself to ferment on the beans.

So, as you can tell from this primer, the various methods used to process the coffee can have a great affect on the outcome of the coffee even before it gets to the roaster—where the darkness of the roast and the roasting method again can dynamically change the produced cup. The possibilities are truly infinite for combinations of processing-to-roasting methods.

I hope this has helped to shed some light on the complexities of coffee processing. Please check out the links in the post for a more in-depth look at these processes, and really appreciate all the work that goes into your cup of morning joe. I urge you to dive into the links within this article to learn more. I attach a lot of additional info in these posts for those who want to know more. There’s links to articles and videos that will totally enrich your knowledge base on the subject, and grow your appreciation of coffee.

Now, Let’s Talk Onyx Geometry Blend

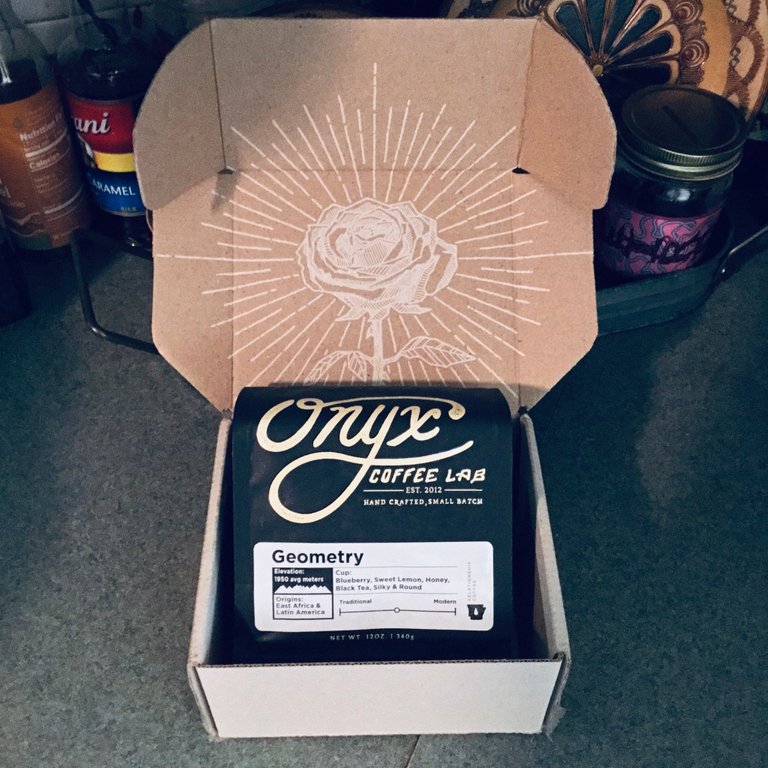

After trying a single-origin from the Onyx offerings, I decided to give one of their blends a go, and I’m super happy I did. This time we’re going to taste Onyx’s Geometry Blend, which is one of their year-round selections. Geometry is a blend of coffee from East Africa and Latin America, it’s grown at an elevation of ~1950-2100 meters above sea level, and its bag boasts notes of blueberry, sweet lemon, honey, black tea, silky & round.

While this coffee is available year-round, they do cycle the individual coffees that go into creating this blend. They start from the end result flavor profile, mentioned above, and work backwards to create this in the cup from their seasonal offerings. It’s a creative approach to creating coffees that stay seasonal, but are also offered year-round. I like the creativity involved in this.

Now—the tasting. First of all, let me just say that I really dig this coffee. Onyx’s tutorials and info resources have said this coffee is easy to dial in and works great as both filter coffee, and as espresso. It’s also the coffee that their coffeehouses use in espresso drinks up to 8oz. It’s diverse, it’s flavorful, and it’s a solid coffee. And it’s true—it’s easy to dial in, and has some great notes that taste great in both small-batch pour overs as well as brewing an entire pot. At $17/12oz, it’s a little expensive for me to drink it every day, but its a super tasty coffee that would work as a reliable everyday blend, for sure.

On the Onyx scale from “traditional” to “modern,” this coffee sits just on the modern side of the middle. This is a washed coffee blend made from washed varieties of Colombian and Ethiopian coffees, so that middle-sitting makes a lot of sense. Colombian coffees have a more traditional flavor, and Ethiopian coffees are oftentimes much fruitier—so the balance really shines in this cup. A washed Colombian gives off more of the dark flavors of the black tea and chocolate notes, and the washed Ethiopian delivers the blueberry notes and the lemon while not being too fruity (there’s not really a coffee that’s too fruity for me personally, but ya know), and still allowing the characteristics of the ground to come through in the beans. The light-medium roast also preserves much of these flavors to the final cup experience, as well, so while the roast is super good on these beans, it also allows the characteristics of the green coffee to come through.

The aroma of Geometry is nice. It really shines. It’s ripe with blueberry notes and sweet milk chocolate, and the tea qualities also ring through at this level. This aroma gives birth to a wonderful flavor with the continuation of blueberry (lighter in taste than in aroma), dried date, cocoa, and a sweet honey note that compliments the entire cup. Its aftertaste is of a resonant black tea, which is also quite pleasant. The mouthfeel of this coffee is both smooth and slightly astringent (it has a hint of lemon), and it has a tangy, mild lemon acidity. It’s a round and very balanced cup of coffee that combines a lot of my favorite attributes into one cup.

I’d love to talk coffee with anyone if you have a particular process method, region, or roaster that you enjoy drinking, and I’m always down to receive suggestions for new roasters and quality coffee to give a whirl. Coffee is so fun and so infinite—I just really love over-analyzing and enjoying coffee. So...I’ll be doing it again sometime soon, for sure.

All stock images are sourced with from Pexels.com, and all image editing is done by me (@jessamynorchard). Hive tag gif made by @derangedvisions.

It's almost 3:30 am.... I really need coffee!

I like Ethiopian coffee cause their fruity taste. Have you tried Gayo coffee or any Indonesian coffee varities? If I were to rank coffee, I would do : Brazilian, Ethiopian, then Indonesian.

I love the fruity taste of Ethiopian coffee, too. As far as Indonesian coffees, I enjoy Sulawesi coffees, but I love wet-hulled coffees from Sumatra—the earthy flavors and the taste of the terroir you get in those can be so good with a light-medium roast. I drank dark-roasted Sumatra for years before I tried lighter roasts, and my world opened up when I finally did. It’s a coffee region that, especially with the volcanically-influenced soils, that has a flavor profile truly different than anywhere else.

I have the most experience with Sumatra Mandheling and Lintong coffees, but literally my favorite Sumatra of all time is a Sumatra Kerinci and is a blend sourced from 680 small producers in the North Kerinci Valley and includes Gayo varietals. Love it. The green bell pepper notes in that cup blew my mind. I actually made a pour over of that coffee today. :)

I have also tasted a lot of coffee from Java, but I haven’t tried any from that region that was not roasted into oblivion—so I’m excited to taste the differences there in a lighter roast.

Yum! You have been curated by @11:30:00 on behalf of FoodiesUnite.net on #Hive. Thanks for using the #foodie tag. We are a tribe for the Foodie community with a unique approach to content and community and we are here on #Hive.

Join the foodie fun! We've given you a FOODIE boost. Come check it out at @foodiesunite for the latest community updates. Spread your gastronomic delights on PEAKD.com and claim your tokens.

Join and Post through the Community and you can earn a FOODIE reward.