This post is an exercise in using my own experiences to illustrate a model that I’m working on for a grant application.

The basic question is: How does SF, broadly defined, influence young people in their choices about scientific careers? How much do the stories themselves matter, and how much the community? The only research on this that I know of is an informal survey by Sigma Xi of its members. So this is my story, which I'll compare with theirs as I try to figure out hooks for further projects.

I was a lonely kid living in a rural area before the Internet.

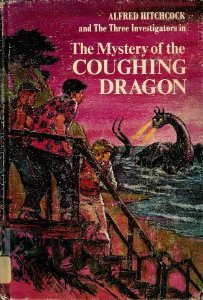

Everybody I knew saw Superman and Star Wars in the theater (except me), but there was no dedicated SF community. There weren’t even comic book stores. I bought my comics off a wire spinner rack at the pharmacy or the grocery store. Any books I read came from a classroom, the school library, or from the Weekly Reader catalog. Nonetheless, I read a LOT of books, many of which I have no titles for at this point. It would be an interesting exercise to try and reconstruct that reading history. There were more mysteries and paranormal books than hard SF, I’m pretty sure. In any case, at this point the relationship with the works themselves was by far the most important thing.

My favorites at age ten, better than the Hardy Boys, or Brains Benton, or Encyclopedia Brown, or even The Mad Scientists' Club.

By high school, I was also reading from the public library and ordering comics from Mile High or Bud Plant, in catalogs I got from my best friend, who had more money than I did and who had become a dedicated collector with specific tastes. We traded comics, but it was mostly one-way because I would read almost anything. By this time we were separately plotting, writing, and drawing our own comics, which we occasionally showed to other people, who mostly did not understand them. I knew that there were conventions, but I never attended any, because that was not the sort of thing my parents would take me to. About this time dedicated comic book stores started to appear in our area, but I did not go to them, for the same reason. I did not write fan letters, and only read them in the letters pages of comics when I was bored (which was often). During this period was when I started to branch out into SF and fantasy. I was actively attempting to balance science, visual arts, and writing in my career plans. If I had known that scientific illustration or science journalism were options, I would almost certainly have gone for something like that over a graduate research degree (no Internet, remember?). I was a practical teen who wanted above all to be living independently, away from my family.

During college, I joined a gamer group that called itself the Miskatonic Student Union.

The group still existed in 2013, but seems to have fallen off the map in the years since.

Or perhaps they've gone mad and been confined to an asylum . . .

This might not seem like SF, but the content of those games was overwhelmingly either SF or fantasy (conspiracy thrillers and detective dramas still have not made their way into successful RPGs, except as flavoring). At its peak, the MSU ran games five nights a week, plus mini-cons each semester. Usually weekends were reserved for parties, movies, and more casual boardgames. There were 25 or so core members, mostly male, and another 50 or so who hung around the edges. This was my first real experience with a dedicated fan community. My peer group had always been “the smart kids” who were on the academic team and took advanced classes (my school only had one AP class at that time -- English -- plus an enrichment program they called "Challenge," which was probably grant-funded) and were actively trying to get into college (a serious minority at that time in that place). There were maybe five other MSU scientists – two physics grad students, two pre-med students, and an electrical engineer. I liked being “the science guy.”

About this time I officially gave up on art as a career, after a botched attempt to get a part-time job drawing T-shirts. I was a biology major, originally thinking either pre-med or wildlife field research, but gravitated towards biochemistry because I liked imagining molecules visually. Also, the pre-meds were hyper-competitive backstabbing bastards who would do really cheap things, like rip the pages out of reserve textbooks in the library. I could not imagine spending thirty years with those people. The white-coat lab research courses available to undergrads were interesting in content but tedious and repetitive in practice. Possibly because of that, I was also kind of a lab klutz. What I really liked were the seminar courses, where I could read other people’s research and write stuff based on their work. I also took several courses in creative writing and literature, including an SF class where I read William Gibson’s Neuromancer, though I preferred Phillip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle. With one summer to make up a failed physics class, I was finished and out in four years.

By graduation, I was really sick of being in school.

I wanted a job, a beer, and a girlfriend. I spent one summer looking for a lab job, couldn’t find one, and then entered the world of menial temp jobs, like bussing tables at the Faculty Club, or guarding a mattress factory, or filing magnetic tapes at a 1990s data center. These had the sole benefit of giving me lots of time to read. I haunted all the used bookstores and traded my finds with my MSU compadres to stretch my budget further. I had given up buying comics because they were too expensive (UK actually had a great comics collection in the King library basement, but I only visited it once or twice). I seem to remember subscribing to Scientific American, or possibly just picking up every one that I ran across. In any case, that’s where I first got interested in brains as a career possibility, as opposed to a subject of SF.

Unemployment and poverty can be powerful motivators.

During that first year, I researched graduate programs and took the GRE. During the second, I applied and interviewed and got a side job tutoring the GRE for the Princeton Review, my first teaching experience outside of study groups. My interviews were my first flights on an airplane – pretty exciting at the time. I applied to ten schools (I think), interviewed at four, and accepted the only offer. I moved to Rochester, NY, knowing no one and moved in with two strangers after sleeping on the floor under my cubicle in the med school grad office for a couple of nights.

At this point, I'm almost perversely proud that I still don't know what the hell "Meliora" means.

Though if I ever have a daughter, that's her name.

Now I was back with “the smart kids,” who were more eclectic in their interests.

Thing was, the Internet was driving SF more and more into mainstream all the time, so suddenly rather than being a weirdo I was just kind of an expert in something that everyone knew about at least tangentially. Plus, we were researchers. The future was not “out there,” it was “right here,” in our labs, under our noses. We played with ideas for a living. Some of us read SF, but kept it kind of quiet because we were supposed to be reading research papers. I compromised by mostly switching to short fiction, which I felt less guilty about. In short stories I discovered the heroin of SF – the purest form of the idea drug. Importantly, I could control the dosage, stopping with just one, which helped me to manage my time. Occasionally I would try to do a novel, one chapter per night, but if it was a good novel, like one of the early volumes of Martin's A Song of Ice & Fire, I would sooner or later get sucked in and lose a night of sleep. This was not ideal.

continued tomorrow